The keys to implementing a successful fertilization plan in the home landscape are to understand a few basics of soil science, to know the nutrient needs of your trees and shrubs, to evaluate what your existing soil has to offer, and to use the right amendment at the right time. Gardeners often have the misconception that adding large quantities of fertilizer will make their plants grow faster or better. Further, they often “feed” plants as a cure-all when they notice problems, when indiscriminately fertilizing a poorly performing plant can actually make the situation worse. Before applying fertilizer, be sure the problem you are treating is a fertility issue rather than another causal agent, such as compacted soil.

Whether you are tending to shrubs or trees in an established landscape or starting with a blank slate, it is paramount to conduct soil tests and use the results to inform your planting and plant care decisions (see “Soil Sampling for Testing” section).

You should fertilize plants to achieve one or more of the following goals:

- ✓ Correct a visible nutrient deficiency.

- ✓ Address a deficiency detected via a soil test or foliar test (used when a soil test is insufficient at diagnosing a potential nutrient problem).

- ✓ Increase vegetative growth, flowering, or fruiting.

- ✓ Increase vitality (vigor) of the plant.

In this publication you will learn the plant nutrients, types of fertilizers available, how to take a soil test, fertilizer application procedures (including timing, rate, and area calculations), how to safely handle and store fertilizers, and some general tips.

Your Site—What to Look for in Your Landscape

In natural ecosystems such as forests, fields, and riparian areas, the soil provides all the nutrients plants need. In urban and suburban developments, however, construction activities alter the soil’s natural profile and physical properties, such as density. Construction activities often remove the topsoil layer, including the organic matter that provides many crucial nutrients, resulting in a loss of fertility. Heavy machinery also compacts the soil, reducing water infiltration and percolation (movement of water through the soil system), making it difficult for recently installed plants to establish new root systems and for older plants to continue growing.

In altered environments, you may need to create planting beds or amend the soil by applying fertilizers, compost (to improve drainage and soil structure), and lime or sulfur (to change the pH). For example, if you want to grow blueberries in your garden, you will need a soil pH of about 5.0 to 5.5. If a soil test indicates that the pH is 6.5, you will need to add a product like sulfur to reduce the pH, which will allow nutrients already in the soil to become available to your plants. In such a case, you may not need to add fertilizer. (See “Soil Sampling for Testing” section for advice on soil testing of large areas.)

Types of Plant Nutrients

Plants require numerous nutrients for optimal growth. They obtain carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen from the air and precipitation. Other nutrients are provided by the soil. Plants typically require large amounts of three primary macronutrients—nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K). Plants also need secondary macronutrients—calcium, magnesium, and sulfur—in relatively large quantities, but not in as high a concentration as N, P, and K. Plants require much lesser amounts of micronutrients, such as manganese and iron, although a micronutrient deficiency can profoundly affect plant health. Table 1 lists the common soil-supplied plant nutrients, their classification, and their function.

For plants to absorb nutrients, the nutrients must be in an ionic form (a naturally occurring form of a nutrient with either a positive or negative electrical charge) and dissolved in soil water. The plant’s ability to take up nutrients also depends on growth stage, stress level, root health, and the quantity and availability of ions. Most soil particles, like clay, have a negative charge, and positively charged ions (such as ammonium and potassium) readily stick to these particles. Some soil particles have a positive charge, and negative nutrient ions (nitrate and sulfate) stick to those. Ions move readily through a well-drained and aggregated soil and into plant roots to meet the nutrient demands of the plant.

Nitrogen exists in many different forms in the soil and atmosphere. It is key to constructing plant proteins and chlorophyll (which gives plants their green color) and therefore critical in the process of photosynthesis. One of the most important sources of nitrogen for plants is organic matter in the soil. Soil microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi decompose organic matter, releasing nitrogen in the ionic forms—ammonium (NH4+) and nitrate (NO3-). The roots of plants absorb both ammonium and nitrate that have been dissolved in water (soil solution). Ammonium is a positively charged ion and readily binds to negatively charged clay particles and organic matter. Nitrate is negatively charged and does not bind well to the soil, which leads to it leaching into groundwater. Because it leaches through the soil rapidly, nitrate-based fertilizer should be applied while plants are actively growing and can access it. Ammonium can be applied throughout the growing season, based on your fertilizer goals, because it remains available in the soil longer.

Urea is another commonly used nitrogen fertilizer that requires special mention; it is a natural form of nitrogen but is commercially manufactured into prills (small pellets) or granules. Urea becomes available to plants after reacting with water and is converted into ammonium and carbon dioxide, often within two to four days after application.

Relative to the other nutrients, plants require large amounts of nitrogen. Symptoms of nitrogen deficiency in deciduous species include overall reduced growth, abnormally small leaves, and chlorosis (yellowing) of the entire plant or primarily the older foliage (Figure 1). Even a plant with a serious nitrogen deficiency may still have new leaves that are greener than older ones because nitrogen moves readily in the plant, and the plant allocates nutrients to younger, more productive foliage. Such symptoms can be helpful in diagnosing a nutrient disorder. A long-term nitrogen deficiency (over many months) can lead to shorter branches, premature fall color, and leaf drop. In conifers, nitrogen deficiency may result in little to no side branching and may cause lower canopy needles to grow too close together, be shorter than those on a healthy plant, and appear yellow.

While nitrogen deficiencies tend to create the most common problems, an overabundance of nitrogen can also negatively affect plants. Overfertilizing with nitrogen may reduce flowering and produce excessive shoot growth. Applying too much nitrogen can also increase pest populations. The resulting overly succulent new growth may attract aphids, scale insects, lace bugs, and other “sucking” pests.

Phosphorus is important in photosynthesis, cell division and enlargement, and respiration (the process by which carbohydrates convert oxygen into energy). It is key in the production, storage, and transfer of energy throughout the plant. Phosphorus also plays a role in initial root formation and growth, as well as in production of flowers, fruits, and seeds. Plants with sufficient levels of phosphorus are more resistant to disease infection because of their vigorous, well-developed root systems.

Phosphorus is highly mobile in the plant, so deficiencies will first become evident in older leaves. As with nitrogen deficiencies, the plant will move phosphorus to young, more productive leaves and allow the older foliage to defoliate if the deficiency is not addressed. Leaves may turn a darker color (dull blue-green, reddish, or reddish-purple) than normal foliage. Severe deficiency may cause very pale foliage.

Trees growing in heavily altered sites or in compacted soils often exhibit phosphorus deficiency (Figure 2). Many urban soils contain insufficient phosphorus, which typically reduces or prevents shoot and root growth. Conversely, farmland and well-established garden sites may have higher than normal phosphorus concentrations. Under the latter conditions, adding fertilizer with phosphorus will not increase growth of garden plants and may harm the environment. Any applied fertilizers, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus, that are not used by the plant may either be bound to the soil or leached into water resources, causing nonpoint source pollution (see “Fertilizer Storage and Handling” section). In addition, overabundant phosphorus may inhibit availability of nutrients such as iron and may cause discolored leaves and weak, unhealthy growth.

A portion of phosphorus binds quickly to soil particles and becomes immobile, or unavailable, to plants. Another fraction of phosphorus is dissolved in soil water and moves very slowly throughout the soil system (only about 1 inch per year) and while in solution is available for root uptake.

Potassium is vital in photosynthesis and helps regulate water status inside plant cells and water movement throughout the plant. It is also critical for ion movement. Potassium deficiency can result in thin cell walls in plant tissues and a reduction in leaf growth, photosynthesis, and productivity. Symptoms of insufficient potassium include weakened stalks and stems, stunted roots, and white or necrotic spots on older leaves (Figure 3). Potassium deficiency can lead to decreased fruit yield and quality and can reduce the plant’s ability to resist attack by fungal, bacterial, and viral organisms, creating susceptibility to disease.

Figure 3. Potassium deficiency in palm exhibited primarily by dead leaf tips and yellowish coloration. Palms are being planted in more areas of North Carolina, not just near the coast, and potassium deficiency is a common issue for them.

Photo courtesy of Tim Broschat, Symptoms of Palm Diseases and Disorders, USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood.org.

Types of Fertilizers

There are many fertilizers on the market, and knowing what nutrients are found in each can help you choose the best product for your needs. The most commonly sold type is a “complete” fertilizer, meaning that it contains the three major plant nutrients—nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium—in the forms of nitrogen, phosphoric acid (P2O5), and soluble potash (K2O), respectively. Manufacturer labels for complete fertilizers represent the composition as a percentage by weight of N, P2O5, and K2O, always listed in that order. For example, the numbers “20-10-10” on the sample product label in Figure 4 indicate a guaranteed analysis of 20 percent nitrogen, 10 percent phosphorus, and 10 percent potassium. To determine how much of each nutrient is provided, you would multiply the percentage of each by the size of the container, which in this example is 40 pounds. Applying that formula, you would calculate that this product contains 8 pounds of nitrogen, 4 pounds of phosphorus, and 4 pounds of potassium, for a total of 16 pounds of the key nutrients. The remainder of the bag consists of filler (typically corncobs, sand, granular limestone, or sawdust) that aids in distributing the fertilizer. Some complete fertilizers may also contain additional nutrients. These also will be listed on the label as a percentage by weight.

“Incomplete” fertilizers contain either one or two of the three major nutrients. They are useful in situations in which the addition of all three key nutrients is not necessary. For example, if a soil test indicates high levels of phosphorus and potassium, you might choose an incomplete fertilizer, such as 21-0-0.

Commercially available fertilizers may be synthetic or natural. Synthetic products are manufactured from minerals, gases, and inorganic materials such as ammonium nitrate and ammonium phosphate. They tend to have higher concentrations of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, and usually plants can take these up very quickly. Examples of synthetic fertilizer include superphosphate, potassium sulfate, and sulfate of potash. Natural products are derived from organic (plant- or animal-based) sources. These products are processed (dried and mixed, composted, or fermented) to make them functional as landscape fertilizers. In general, natural products contain less N-P-K than the synthetic options and are available to plants more slowly. Therefore, natural products may be required in larger quantities compared to synthetic fertilizers to meet the desired nutrient needs. Some examples of natural fertilizers include manure, bone meal, cottonseed meal, compost, and kelp.

The diversity of fertilizer types and brands can be overwhelming. There are advantages and disadvantages to each category of fertilizer. Consider multiple factors when selecting a product—the most important being the reason for fertilization. For example, are you trying to increase plant growth or vitality or improve flower production? If so, what nutrients are required to accomplish these goals? Soil test recommendations typically suggest using a complete fertilizer (N-P-K), either with or without other nutrients included. Another critical consideration is the type of nitrogen in the fertilizer, as this directly relates to its availability to the plant. Table 2 provides a list of some common fertilizer components, their nutrient content, how quickly the nutrients are available to the plant, and how they affect soil pH. Synthetic fertilizers tend to have higher concentrations of each element and usually are available relatively quickly after application. Most natural options have lower concentrations of nutrients that are available over a longer period.

| Product | Nutrient Content % | Plant Availability Rate | Effect on pH | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | P2O5 | K2O | |||

| Ammonium sulfate | 21 | 0 | 0 | quick | very acidic |

| Ammonium nitrate | 35 | 0 | 0 | quick | acidic |

| Calcium nitrate | 12 | 0 | 0 | quick | alkaline |

| Sodium nitrate | 16 | 0 | 0 | very quick | alkaline |

| Diammonium phosphate | 18–21 | 46–53 | 0 | quick | acidic |

| Triple superphosphate | 0 | 48 | 0 | medium – slow | neutral |

| Potassium chloride | 0 | 0 | 60 | quick | neutral |

| Potassium nitrate | 13 | 0 | 44–46 | quick | alkaline |

| Urea | 46 | 0 | 0 | quick | acidic |

| Sulfur-coated urea | 22–38 | 0 | 0 | medium | acidic |

| Sewage sludge* | 2–6 | 3–4 | 0–0.5 | slow | slightly acidic |

| Dried blood meal* | 12–15 | 3 | 0.6 | medium | slightly acidic |

| Bone meal* | 2–4 | 22–28 | 0–0.2 | slow | alkaline |

| Cow manure* | 1.5 | 1 | 1.5 | medium | neutral |

| Chicken manure* | 2–3 | 1 | 1–2 | slow | highly variable |

| Wood ash* | 0 | 2 | 8 | slow | alkaline |

Yellow highlight and asterisks indicate natural fertilizers. ↲

Synthetic fertilizers are manufactured to be either quick-release or slow-release. Quick-release formulations become available to plants as soon as they encounter soil water. They are available for a short time, usually about two to four weeks. Because most synthetic fertilizers are highly soluble salt formulations, excessive applications of quick-release fertilizers can increase salt concentrations in the soil and burn or kill young roots. Take care to apply only the amount necessary.

Slow-release fertilizers are manufactured to discharge nutrients slowly, making them available to plants over a long period, typically many months. Manufacturers coat some slow-release products with resin or plastic. Release rates depend on the coating type and thickness, as well as the temperature and water content of the soil or growing media. Often, there is a significant release of fertilizer during the first two to three days after application, and then more nutrients become available slowly over six months to a year, depending on the product. It is best to use slow-release products for tree and shrub fertilization, unless a slow-release option will not meet your specific needs.

Fertilizer: Which Type is Best?

Slow-release

Pros

- ✓ Good for established plants

- ✓ Usually lasts six to eight weeks (longer depending on formulation)

- ✓ Doesn’t force unnaturally rapid plant growth

- ✓ Less likely to leach into groundwater

- ✓ No need to water in

Cons

- ⤫ Nutrients not immediately available to plants

- ⤫ Lower concentration of nutrients

- ⤫ May be more expensive

- ⤫ Less effective in cool soil

Quick-release

Pros

- ✓ Nutrients immediately available to plants

- ✓ Soluble nitrogen easily dissolves upon contact with soil water

- ✓ Can stimulate fast green-up

- ✓ Typically cheaper than slow-release products, based on nitrogen concentration

Cons

- ⤫ May lead to leaching, particularly nitrate (NO3-) forms of nitrogen

- ⤫ Lasts only a short period

- ⤫ Excessive application can lead to root damage or death of young plants

Natural fertilizers often are effective slow-release products. Soil microbes must break down these natural forms of nutrients into inorganic ions for them to become available for root uptake. Table 3 lists a few common natural fertilizers and the nutrient content of each; most of these have relatively low concentrations of nutrients compared to synthetic fertilizers. Air and soil temperature, soil moisture, and soil composition (soil texture and organic matter content), as well as the population of soil microorganisms, affect the rate of decomposition of these products. In addition to providing nutrients, natural materials may also increase soil organic matter content, soil tilth (the workability of the soil), and soil aggregation (the clumping of soil particles together, which allows better movement of water, nutrients, and roots).

Whether you use a synthetic or natural fertilizer, there are two main forms to choose from—granular or liquid. Granular products are popular, relatively inexpensive, and an effective method of distributing nutrients. Liquid fertilizers are usually sold in a concentrated formulation (derived from either synthetic or natural sources) designed to be mixed with water and applied as a foliar spray, soil drench, or soil injection. Formulation options are discussed further in the “Fertilizer Application” section.

Soil pH and Nutrient Availability

Soil pH is a significant factor to consider when assessing plant health in your landscape. Understanding soil test results relating to pH is a key piece of the puzzle when troubleshooting and correcting plant nutrient deficiencies, as the acidity or alkalinity of soil greatly affects the availability of elements to the plant. For example, an iron deficiency in a holly may cause symptoms such as interveinal chlorosis and foliage that is smaller than typical for the species. If the soil pH is higher than 6.5, iron binds to the soil and is unavailable to the plant. In this case, applying supplemental iron to correct the deficiency would be a short-term solution. Such an application, while appropriate, would address only the symptom and not the cause of the problem. To achieve a long-term solution, you would need to amend the soil to lower the pH, which would enable iron to be consistently available to the plant. Sulfur is often used to lower soil pH, while lime is a common amendment used to raise the pH.

Figure 5 illustrates how soil pH affects nutrient availability; for each nutrient, the wider the black bands are, the greater the availability of the nutrient at a corresponding pH. For example, nitrogen has greater availability for pH values ranging from about 5.5 to 8.5, and magnesium is readily available at a pH of 6.0 to 8.5. The blue band in the figure illustrates the pH range at which almost all nutrient elements are readily available to plants (6.0 to 6.5).

Symptoms of Poor Plant Growth and Potential Causes

Symptoms

- Light-green or yellow leaves

- Dead spots on foliage

- Smaller-than-normal foliage

- Defoliation

- Fewer or smaller flowers and fruit

- Short twigs

- Dieback or dead branches

- Wilting foliage

Potential Causes

- Compacted soil

- Inadequate aeration

- Inadequate moisture

- Adverse climatic conditions (temperature too hot or cold, air pollution, improper light)

- Improper pH

- Wrong plant species for the site conditions

- Improper planting

- Girdling roots

- Mechanical damage

- Salt damage

- Pest damage, diseases, destructive nematodes

- Nutrient deficiency or toxicity

- Excessive nitrogen

Did you know that annual raking can remove as much as 3 pounds of nitrogen per 1,000 square feet that could have gone into the soil? One effective, inexpensive way to enhance soil fertility in your yard is to retain natural plant materials on site. For example, instead of disposing of fallen leaves, add them to planting beds and place them around trees. This improves soil and provides food for beneficial soil organisms.

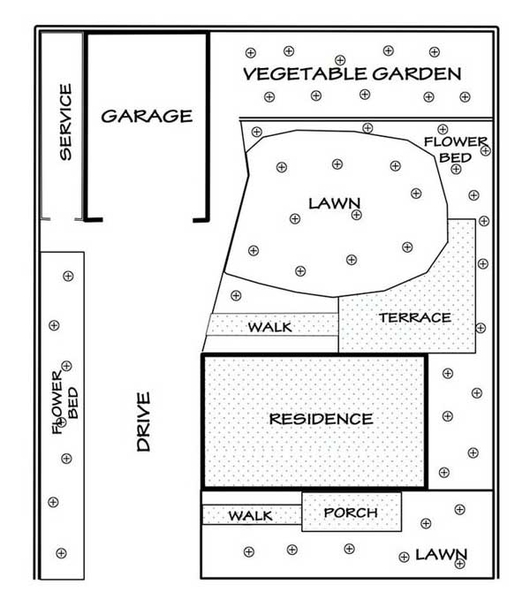

Soil Sampling for Testing

The North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services (NCDA&CS) Agronomic Services Division provides free (depending on the time of year) or low-cost soil testing to North Carolina residents for properties of 1 acre or smaller. Agronomic Services—Soil Testing for Homeowners provides comprehensive instructions. The NC State Extension publication AG-614, A Gardener’s Guide to Soil Testing also contains helpful tips. You should sample each distinct area of your landscape separately (Figure 6), taking multiple samples from each area and mixing them together in a bucket to create a composite sample. Collection boxes and submission forms are available from the Agronomic Services Division at 4300 Reedy Creek Road in Raleigh or your local N.C. Cooperative Extension center.

The testing lab will email you when your tests are complete, and you can access your report online. The report provides information about your soil’s pH, cation exchange capacity (measurement of the soil’s ability to hold on to positively charged nutrient ions, such as ammonium), and the status of some key nutrients.

The soil tests done by state agencies do not test for nitrogen concentrations because levels are so inconsistent and nitrogen does not persist long in soil. Soil reports provide a nitrogen recommendation based on the known requirements of the plant species that you specified on the sample information form. (If you are interested in knowing the nitrogen levels in the soil, you would need to send the samples to a specialty lab, which is costly. Typically, only researchers need such advanced data.)

With your soil test results in hand, you can then plan and implement an appropriate fertilization program.

Fertilizer Application: Timing, Area, and Rates

Fertilizers can be applied in granular or liquid form.

Apply granular products with a drop-type, hand-held, or cyclone spreader to distribute the fertilizer evenly over the target area. Because granules need contact with the soil to be most effective, apply just before rain is forecast or irrigate afterward to wash fertilizer off any foliage and to help nutrients break down and move into the soil. In shrub beds, it is advisable to rake away any mulch, apply granular fertilizer, water it in, and then move the mulch back in place.

Mix liquid fertilizer with water according to the package instructions and apply it to the foliage of your plants and the soil around them. For small applications, you can dilute the fertilizer in a watering can and sprinkle around the base of the plants. You can use a sprayer to fertilize multiple plants. A hose-end sprayer is most commonly used for lawn and shrub applications. Liquid fertilizers typically are quick-release formulations that are readily available to plant roots. Be sure to apply these products evenly over the entire root area and use the correct dilution rate.

When liquid fertilizers are used as foliar applications, the plants absorb the nutrients directly through the leaves. This method of application often is intended as a quick fix for a visible nutrient deficiency, such as chlorosis. If using foliar sprays to correct deficiencies of a micronutrient, such as iron, apply just before or during the growing season. The effects of this type of application can be relatively short-term, lasting a year at most.

Proper timing of fertilizer applications depends on multiple factors, including the geographic location, season, plant species, plant growth stage, and the type and form of fertilizer. The ideal time to apply fertilizers is when the plants are actively growing. In general, root growth for most tree and shrub species begins before budbreak in spring and continues through fall. As long as soil temperatures are above freezing, roots can grow.

In locations with sandy soils, heavy rainfall, or routinely irrigated landscapes, it may be advisable to make several applications of lower rates of fertilizer throughout the season, especially if using quick-release forms. On dry sites or in soils with a high clay content, apply fertilizer less frequently at a higher rate. For example, if your soil is more clay than sand, and the soil test recommends applying 10 pounds of a 20-10-10 fertilizer, you may choose to apply it all at once in spring. If, on the other hand, your soil is more sand than clay, you might decide to make four applications of 2 1/2 pounds each.

No matter the soil or fertilizer type, avoid fertilizing during periods of drought or plant stress. Also, avoid using quick-release fertilizers between leaf drop and budbreak; without leaves, the plant is not actively cycling water and nutrients. Because fertilizer uptake would be minimal during that period, excess fertilizer may leach into groundwater or volatilize into the atmosphere. Volatilization (loss of material from liquid or solid to a gas state) can occur if ground temperatures are below freezing or above 70ºF, soil is overly wet, soil pH exceeds 7.0, or conditions are very windy.

Timing of slow-release fertilizers is less critical because they provide nutrients over a longer period. Fall applications are effective, or you may want to split recommended application rates evenly between spring and fall, when roots are actively growing. Split applications are also a good option in clay soil types. Fall application has not been found to predispose plants to winter injury unless the plant is stressed by other factors, such as shearing or being grown outside its normal range.

Urea is one example of a slow-release product. It is coated with sulfur, which controls the rate of nitrogen release. This product is often less expensive than other slow-release fertilizers (such as Osmocote® or Milorganite®), and it supplies sulfur. Therefore, if your soil test indicates you need to lower the pH, adding sulfur-coated urea can help. Incorporate urea products into the soil to avoid volatilization. It is best to apply to dry soil in cool weather.

If supplemental phosphorus is needed, incorporate granular forms into the soil during bed preparation and water the fertilizer in. Liquid forms may be applied as a drench over the plant roots. (Note that if applied as a drench, the phosphorus will quickly bind with the soil; therefore, it is best to apply it when roots are actively growing.) Finally, you can supply soil phosphorus by incorporating organic matter such as compost or manure products; microbes will decompose this material, adding phosphorus ions into the soil solution and making them readily available for plant uptake.

Potassium is relatively immobile in soils, binding with both clay and organic matter particles. Therefore, it is best to incorporate potassium fertilizer products prior to planting. In clay and organic soils, a single application may suffice; in sandy soils, however, you may need to apply smaller amounts more frequently.

General Application Tips

- ✓ Apply when plants are actively growing.

- ✓ Do not apply fertilizers on bare soil.

- ✓ Incorporate fertilizers into the soil when possible or irrigate after surface application.

Application area should correspond to the portion of ground over the roots of target plants—this might be a single shrub or an ornamental bed with multiple plantings. When fertilizing trees, it is important to remember that the roots grow from near the trunk to well beyond the drip line of the tree—the surface area under the entire tree canopy. Research has shown that to maximize availability of fertilizer to the plantings, you should apply it within the drip line. Imagine dropping an empty cylinder over a tree at the edge of the canopy (Figure 7). The area on the ground within the cylinder is the drip line.

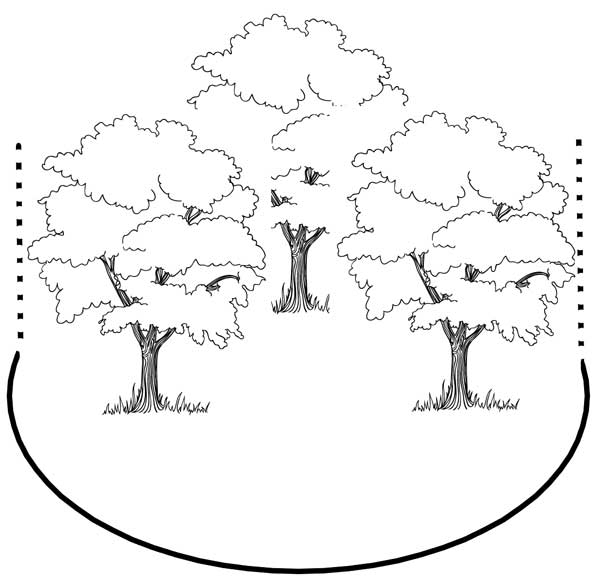

When fertilizing a group of trees that share a root zone, treat the area within the cumulative drip line (Figure 8).

The rate of fertilizer to apply should be based on the soil nutrient status (determined from a soil test) and the desired goals of fertilization. If the objective for fertilizing young trees is to encourage rapid growth, a general recommendation is to apply a relatively high rate of nitrogen (2–4 lb/1,000 sq ft/year). The goal for mature trees is typically to maintain tree vitality. A typical nitrogen application rate for mature trees is 1–2 lb/1,000 sq ft/year. Trees in good health may not need fertilization.

Regardless of their growth stage, plants in nutrient-deficient soils can benefit from properly applied fertilizers. Slow-release fertilizers should be used unless the nutrient objective cannot be met with those products.

After selecting a fertilizer product and determining the size of the area where it will be applied, calculate the application rate. Following is a simple example for calculating application rate.

Sample Problem

Your fertilizer is 10-10-10 (N-P-K), a common fertilizer product. The soil test indicates that you should apply this at a rate of 20 lb/1,000 sq ft. You will be applying to a circular shrub bed with a diameter of 15 ft. The radius = 7.5 ft (half the diameter of a circle).

Bed area = πr2, where: π = 3.14 and r (radius) = 7.5 ft (half of the diameter)

3.14 × 7.5ʹ × 7.5ʹ = 176.6 sq ft, rounded to 177 sq ft.

How many pounds of 10-10-10 fertilizer are needed for the 177 sq ft bed? Set up a ratio solving for x, per the following example:

\(\frac{20\ lb\ fertilizer}{1,000\ sq\ ft}=\frac{x\ lb\ fertilizer}{177\ sq\ ft}\)

x (lb) × 1,000 sq ft = 20 lb × 177 sq ft

x = 3.5 lb fertilizer (This is the amount you will apply to your circular shrub bed.)

Figure 8. Because the trees pictured here share a root zone, calculating the amount of fertilizer for the entire area is more accurate. In this case, you would calculate the area of a circle encompassing the drip lines of all the trees as one, using the same formula for the area of a circle.

Illustration by Barbara Fair.

When to Consult a Professional

Many arborists use a pressurized subsurface, liquid-injection system to get fertilizer into the soil about 4 to 8 inches deep (Figure 9). Injections are spaced evenly about 2 feet apart within the drip line of the tree. This method gets the fertilizer below turf roots to the fibrous, absorbing roots of the tree and minimizes runoff. The process also may have a positive effect on soil structure by reducing compaction. Many arborists use a mixture of components that may include natural ingredients, such as kelp, biostimulants, and humic acids. Consult an International Society of Arboriculture (ISA) Certified Arborist®, a professional with years of experience who has passed an exam given by the ISA certification board; the credential indicates that this person is dedicated to improving their knowledge base and employs well-established practices developed by research and industry standards.

Fertilizer Storage and Handling

All fertilizers are chemicals, and you should handle them with care. Store fertilizers in a dry, well-ventilated location. Some granular fertilizers, if they become damp, can clump together or even change chemical composition. Keep bags off of the ground or floor. You might purchase a cabinet specifically for fertilizer storage, keeping it locked and well labeled. Many of the ingredients in fertilizers are flammable or explosive, so store them away from ignition sources. No one should smoke in the storage area or around fertilizers at any time.

Apply only the amount of fertilizer indicated by a soil test. If you are mixing fertilizer with water, work on an impermeable surface, like a level driveway. If you spill any liquids, immediately clean them up using an absorbent material like sand or cat litter. After applying granular fertilizer, blow or sweep any spilled material off hardscape areas into the beds or turf to reduce the chance of runoff.

If used improperly, fertilizer can escape lawns and planted areas and cause serious problems in the surrounding environment. Excess nitrogen and phosphorus can leach through soil and pollute groundwater or run off the landscape into waterways. Runoff of nutrients into nearby ponds, lakes, streams, and estuaries is known as nonpoint source pollution. High levels of nitrogen and phosphorus in these waterways can increase algal growth and deplete oxygen in the water, causing harmful algal blooms (Figure 10) that can be lethal to fish or injure other aquatic life.

Wrap-Up

Fertilizing woody plants is a straightforward process once you understand a bit of soil science. Start with a soil test to provide a baseline of your soil’s health. Have a clear objective prior to fertilizing your plants. Be aware that many problems observed in trees and shrubs may not be due to a lack of nutrients, but rather other factors such as drought, compacted soil, or poor planting technique. If you have questions or need assistance, contact your local N.C. Cooperative Extension Center or an ISA Certified Arborist®.

Glossary

Adventitious shoots—branches arising from a stem or parent branch and having no connection to apical meristems; often sign of plant stress.

Biostimulants—microorganisms, algae preparations, plant and animal extracts, and fulvic and humic acids that are used as a plant fertilizer.

Cation exchange capacity (CEC)—measurement of the number of cations that can be retained on soil particle surfaces; measured in milliequivalents per 100 grams of soil. CEC values are included in soil test results.

Chlorosis—whitish or yellowish leaf discoloration caused by lack of chlorophyll; often caused by nutrient deficiency.

Complete fertilizer—fertilizer blend or mix that contains the three main plant nutrients: nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K), in the forms of potash, phosphoric acid, and nitrogen.

Drip line—a boundary on the soil surface delineated by the outermost branch spread of a single tree canopy or grouped tree canopies.

Granular fertilizer—pellets or coarse powders that contain a mix of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium and are meant to break down slowly over a period of months.

Humic acids—a group of molecules that bind to and help plant roots receive water and nutrients. Humic acids, fulvic acid, and humin are all substances considered humus—a general term that describes a group of separate, but distinct humic substances—soil organic matter that is decomposing at various rates.

Liquid fertilizer—extracts of soluble powders or chemicals (may be liquid or dry concentrates) that have a mix of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium and are dissolved in or can be dissolved in water and sprayed onto foliage or applied as a drench.

Macronutrients—elements that plants need in relatively large concentrations.

Micronutrients—elements that plants need in only small concentrations.

Natural fertilizer—products that contain organic nutrients that are vital to plant growth and development; examples include manure, bone meal, and compost.

Nonpoint source (NPS) pollution—diffuse sources of natural and human-made pollutants transported by rainfall or snowmelt moving over and through the ground. This runoff enters lakes, rivers, wetlands, coastal waters, and groundwater.

pH—an indication of the acidity or alkalinity of soil. The pH scale goes from 0 (most acidic) to 14 (most alkaline). A pH of 7 is considered neutral. Many plants prefer a pH of about 6.5.

Photosynthesis—a process in which green plants (and algae and some bacteria) convert light energy to manufacture glucose (chemical energy) from water and carbon dioxide.

Quick-release fertilizer—a mixture of nutrients, particularly nitrogen, that dissolve quickly in soil and are readily available to growing plants; examples include ammonium nitrate and sodium nitrate.

Respiration—in plants, process by which carbohydrates convert oxygen into energy.

Slow-release fertilizer—a mixture of nutrients that dissolves slowly, supplying nutrition to plants over a long period; typically sold in pellet form and coated with resins and plastic. An example is sulfur-coated urea.

Soil nutrient cycle—a system by which energy and matter are transferred between living organisms and nonliving parts of the environment. For example, animals and plants consume nutrients that exist in the soil, then release these nutrients back into the environment when they die and decompose.

Soil solution—the medium in which surface and solution reactions occur. This aqueous solution contains dissolved matter from soil chemical and biochemical processes and from exchange with the hydrosphere and biosphere.

Synthetic fertilizer—Nutrient sources composed of synthesized nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium.

Publication date: Feb. 6, 2025

AG-613

Recommendations for the use of agricultural chemicals are included in this publication as a convenience to the reader. The use of brand names and any mention or listing of commercial products or services in this publication does not imply endorsement by NC State University or N.C. A&T State University nor discrimination against similar products or services not mentioned. Individuals who use agricultural chemicals are responsible for ensuring that the intended use complies with current regulations and conforms to the product label. Be sure to obtain current information about usage regulations and examine a current product label before applying any chemical. For assistance, contact your local N.C. Cooperative Extension county center.

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.