Introduction

The longhorned tick (previously called the 'Asian longhorned tick'), Haemaphysalis longicornis, gets its name from anatomic spurs associated with the mouthparts (Figure 1a & Figure 1b). It is an invasive tick spreading throughout the eastern United States and is native to the Far East. Originally from China, Japan, and Korea, it was introduced to New Zealand, Australia, and several Pacific islands. This species was first introduced to the US mainland in 2010, and has been reported from 20 states and Washington DC, including North Carolina, where (as of July 2024) it was found in thirty NC counties: Alexander, Ashe, Avery, Buncomb, Caldwell, Catawba, Cleveland, Davidson, Davie, Guilford, Haywood, Henderson, Iredell, Lincoln, Macon, Madison, Mecklenburg, Pender, Polk, Randolph, Rowan, Rutherford, Stanly, Stokes, Surry, Yadkin, Yancy, Wake, Wautaga and Wilkes.

Biology

Females of this tick can reproduce either sexually by mating with a male, or by producing offspring without mating (parthenogenetically). Only the asexual (parthenogenic) form has been identified in the United States. Regardless of the sexual form, adult female ticks may produce from about 900 to 3,300 eggs in a one-time event. Developmental time from egg to adult averages 89 days (Hoogstral et al. 1968). The feeding stages are active for 57 days. As a result of these biological adaptations, the parthenogenic form of this tick has the potential to reach exceptionally high densities in a few months with all offspring being female.

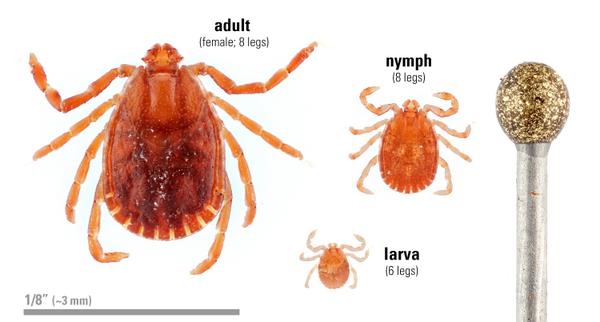

This three-host tick has a wide host range, capable of feeding on different animals for each of the three life stages (larva, nymph and adult; Figure 2). Full engorgement may take from 3 to 6 days for each life stage depending on the host. Typically, the larva acquires a host (usually a small mammal), feeds fully and drops off the host to molt to the next life stage. This is also true for the nymph. Adults acquire a new host and, after feeding fully, it drops off the host to lay its eggs. Female ticks die after laying their eggs. If no other hosts are available, each life stage may feed on the same host, pastured cattle for example (Rainey et al. 2018). As a result, the highest number of ticks found are usually in pastures. All three life stages may be found on host animals or in the environment (Figure 2).

Damages

This tick is an important pest of livestock in Australia, East Asia, and the Western Pacific region. Heavy infestations can cause severe blood loss, poor growth and development, and transmit disease to animals. Known hosts for this tick include domestic cats, dogs, cattle, goats, horses, and sheep. Wild hosts include white-tailed deer, coyotes, foxes, groundhogs, Virginia opossums and raccoons. This tick has been occasionally found attached to humans and birds.

The longhorned tick is a vector of several pathogenic agents in its native range including Anaplasma, Babesia, Borrelia, Ehrlichia, Theileria and Rickettsia that cause disease of humans and animals (Beard et al. 2018). There is evidence that longhorned ticks harbor certain disease causing viruses. Raney et al. 2022 demonstrated Heartland virus carried over from infected adult ticks to their offspring through transovarial transmission, and Cumbie et al. 2022 detected Bourbon virus in field collected ticks in Virginia. Because the disease transmission potential is significant with this tick, on going pathogen transmission studies are underway. A recently-published laboratory study (Bruenner et al. 2019) found that longhorned ticks were not capable of transmitting the pathogen that causes Lyme Disease. However Theileria orientalis Ikeda, a debilitating disease of cattle linked to anemia and abortion, was identified in ticks collected in Virginia (Thompson et al. 2020, Dinkel et al. 2021). Severe tick infestations in cattle can cause anemia, weakness, blood loss and death (Hoogstraal et al. 1968). Tick infestations in New Zealand and Australia reduced dairy production up to 25% (Hoogstraal et al. 1968, Heath 2016).

Producers are advised to examine your animals regularly around the ears, dewlap, udder and perianal region. Cattle should be checked anytime they are brought up for routine procedures, ear tagging, vaccinations, artificial insemination or pregnancy checks. Collected ticks should be stored in alcohol and delivered to your county extension office for identification.

Protection

Personal protection should include wearing insect repellent and treating clothing with approved permethrin repellent. Protecting pets with an approved acaracide and reapplying according to label directions is recommended. Contact your veterinarian for a list of approved pet products for tick control. Treating livestock with pyrethroid sprays or pour-on insecticide will provide protection for those animals. Acaracides formulated for backrubbers and dust bags are effective self-treatment tools for livestock providing that these devices are maintained regularly. Botanical acaracides are showing promise for tick control but have not been evaluated for this species (Singh et al. 2018). Environmental treatments, including mowing pastures in conjunction with on-animal treatments may be considered (Park et al. 2019, Bickerton et al. 2021, Butler and Trout Fryxell 2023). See the NC Agricultural Chemical Manual for a list of available products (https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/north-carolina-agricultural-chemicals-manual). Read the label fully before applying any pesticide. Investigations into entomopathogenic fungi for environmental treatments are progressing (Lee et al. 2019).

References Cited

Beard, C.B., Occi, J., Bonilla, D.L., Egizi, A.M., Fonseca, D.M., Mertins, J.W., Backenson, B.P., Bajwa, W.I., Barbarin, A.M., Bertone, M.A. and Brown, J., 2018. Multistate infestation with the exotic disease–vector tick Haemaphysalis Longicornis—United States, August 2017–September 2018. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(47), p.1310.

Bickerton, M., McSorley, K. and Toledo, A., 2021. A life stage-targeted acaricide application approach for the control of Haemaphysalis longicornis. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases, 12(1), p.101581.

Breuner, N.E, S.L. Ford, A. Hojgaard, L. M. Osikowicz, C. M.Parise, M. F. Rosales Rizzoa, Y. Bai, M. L. Levin, R. J.Eisen, and L. Eisena. 2020. Failure of the Asian longhorned tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis, to serve as an experimental vector of the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases. Elsevier G<bH

Butler, R.A. and Trout Fryxell, R.T., 2023. Management of Haemaphysalis longicornis (Acari: Ixodidae) on a cow–calf farm in East Tennessee, USA. Journal of Medical Entomology, 60(6), pp.1374-1379.

Cumbie, A.N., Trimble, R.N. and Eastwood, G., 2022. Pathogen Spillover to an Invasive Tick Species: First Detection of Bourbon Virus in Haemaphysalis longicornis in the United States. Pathogens, 11(4), p.454.

Dinkel, K.D., Herndon, D.R., Noh, S.M., Lahmers, K.K., Todd, S.M., Ueti, M.W., Scoles, G.A., Mason, K.L. and Fry, L.M., 2021. A US isolate of Theileria orientalis, Ikeda genotype, is transmitted to cattle by the invasive Asian longhorned tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis. Parasites & Vectors, 14(1), pp.1-11.

Heath, A.C.G., 2016. Biology, ecology and distribution of the tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis Neumann (Acari: Ixodidae) in New Zealand. New Zealand veterinary journal, 64(1), pp.10-20.

Hoogstraal, H., Roberts, F.H., Kohls, G.M. and Tipton, V.J., 1968. Review of Haemaphysalis (Kaiseriana) longicornis Neumann (resurrected) of Australia, New Zealand, New Caledonia, Fiji, Japan, Korea, and northeastern China and USSR, and its parthenogenetic and bisexual populations (Ixodoidea, Ixodidae). The Journal of parasitology, pp.1197-1213.

Lee, M.R., Li, D., Lee, S.J., Kim, J.C., Kim, S., Park, S.E., Baek, S., Shin, T.Y., Lee, D.H. and Kim, J.S., 2019. Use of Metarhizum anisopliae sl to control soil-dwelling longhorned tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis. Journal of invertebrate pathology, p.107230.

Park, G.H., Kim, H.K., Lee, W.G., Cho, S.H. and Kim, G.H., 2019. Evaluation of the acaricidal activity of 63 commercialized pesticides against Haemaphysalis longicornis (Acari: Ixodidae). Entomological Research.

Rainey, T., Occi, J.L., Robbins, R.G. and Egizi, A., 2018. Discovery of Haemaphysalis longicornis (Ixodida: Ixodidae) parasitizing a sheep in New Jersey, United States. Journal of medical entomology, 55(3), pp.757-759.

Raney, W.R., Perry, J.B. and Hermance, M.E., 2022. Transovarial Transmission of Heartland Virus by Invasive Asian Longhorned Ticks under Laboratory Conditions. Emerging infectious diseases, 28(3), p.726.

Singh, N.K., Miller, R.J., Klafke, G.M., Goolsby, J.A., Thomas, D.B. and de Leon, A.A.P., 2018. In-vitro efficacy of a botanical acaricide and its active ingredients against larvae of susceptible and acaricide-resistant strains of Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus Canestrini (Acari: Ixodidae). Ticks and tick-borne diseases, 9(2), pp.201-206.

Thompson, A.T., White, S., Shaw, D., Egizi, A., Lahmers, K., Ruder, M.G. and Yabsley, M.J., 2020. Theileria orientalis Ikeda in host-seeking Haemaphysalis longicornis in Virginia, USA. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases, p.101450.

Publication date: Sept. 19, 2019

Reviewed/Revised: July 10, 2024

Recommendations for the use of agricultural chemicals are included in this publication as a convenience to the reader. The use of brand names and any mention or listing of commercial products or services in this publication does not imply endorsement by NC State University or N.C. A&T State University nor discrimination against similar products or services not mentioned. Individuals who use agricultural chemicals are responsible for ensuring that the intended use complies with current regulations and conforms to the product label. Be sure to obtain current information about usage regulations and examine a current product label before applying any chemical. For assistance, contact your local N.C. Cooperative Extension county center.

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.