Introduction

A yard covered in red mounds, with more appearing each day. When disturbed, its tiny defenders rush forth with painful stings and overwhelming numbers. To many homeowners, these impossible-to-overlook insects mean frustration and worry — this is the Red Imported Fire Ant (RIFA) (Figure 1). The RIFA is an invasive species that has now spread across nearly all of the Southern United States and continues to expand its territory northward each year. Given how broadly these ants have established themselves, currently in nearly every county in North Carolina, it is critical to manage and prevent the spread of these pests whenever possible. As such, in this publication, we go over the basics of RIFA biology, behavior, and the potential risks that these ants can pose to individuals and structures.

Colony Structure

From Egg to Worker

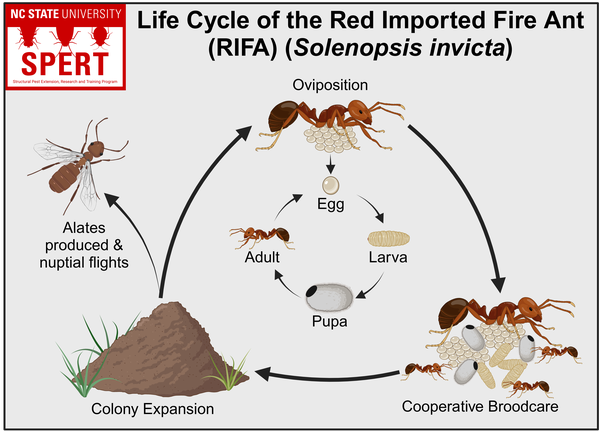

As will all insects, and ants, red imported fire ants begin their lives as an egg. Taking a step back, however, RIFA colonies begin from a single newly mated queen (alate) who goes to ground, finds a safe and isolated chamber, and lays her first clutch of eggs (Figure 2). Within this chamber, she tends to these first eggs until they hatch into larvae, and upon hatching, she begins to feed them part of her own body — her dissolved wings which she will never use again. Once they have grown enough, they will pupate, surrounding themselves in a protective layer, and completely changing the shape and structure of their body into the form of a “typical” ant (Figure 2). Once enough time has passed, adult worker ants will emerge from the pupae, assuming responsibilities of the colony and giving the new queen the freedom to transition into an egg-laying machine. This cycle from egg, to larvae, to pupae, and finally to adult is known as holometabolous (complete) metamorphosis and continues as the colony grows easily into the thousands, and can even incorporate multiple queens and spanning networks of mounds (Figure 2). In fact, a single mature RIFA queen is able to produce up to 5,000 eggs per day. At this growth rate, a colony is typically able to produce a new generation of winged reproductives (alates) after only 6-12 months.

Colonies may be monogyne — single queened, or polygyne — multiple queens. It goes without saying that colonies with multiple queens grow and spread much faster than those with single queens. In general, monogyne colonies are more territorial and aggressive towards other RIFA colonies. As such, they tend to spread further during nuptial flights - see below - and have smaller overall colonies. Polygyne colonies can reach hundreds of queens, sprawling across landscapes and potentially devastating local species. These colonies are more likely to be spread by human activities.

Division of Labor

RIFA, just like all other ants, are categorized as “social” insects, specifically they are “eusocial” insects alongside termites and some bees and wasps. To be classified as eusocial, insect colonies must exhibit a few specific characteristics. These are:

-

Cooperative broodcare: Members of the colony work together to raise each successive generation, taking the wellbeing and future of the colony as a joint and collaborative effort.

-

Overlapping generations: Members of the colony are varying in age, but multiple generations of workers share responsibility, interact, and are responsible for the survival and upkeep of the colony.

-

Reproductive division of labor: All workers in the colony are female, but despite this, they are assigned as workers from birth, whereas the female queen is solely responsible for egg production and the growth of the colony. This “work assignment” is hardcoded into the insect.

In the case of ants, and other eusocial insects as well, there is a finer-tuned division of labor within the workers. Those that are younger and “more valuable” to the colony tend to perform tasks within the mound — feeding larvae, tidying, expanding, and transporting collected food to areas of storage (Figure 3). Older workers, which are often viewed as “more expendable” typically perform the more dangerous task of foraging for food and leaving the safety of the mound. With this clear division, and commitment of the colony to the system under the command of the queen(s), colonies are able to thrive and expand at alarming rates.

Reproduction

As RIFA colonies continue to grow and expand they begin to shift focus towards the biological goal of reproduction. In the case of fire ants, and all other ant species, this culminates in the production of both male and female alates — winged reproductive colony members that will take to the sky in search of a mate — called a nuptial flight (Figure 4). Alates are able to fly up to roughly 3 miles under their own strength but may travel much farther with the assistance of wind. Males often take to the skies first and resemble wasps rather than an ant with wings. Female alates follow shortly after and will mate once during the flight, after which she lands. Males die shortly after mating, having fulfilled their purpose, and the females remove their wings to begin a colony.

Foraging & Mounds

Foraging

Worker ants will forage for food nearby the mounds by traveling underground in tunnels that lead to the surface, or by travelling in oscillating patterns away from the nest. Using these methods, they search for odors associated with food and lay pheromone trails to lead fellow workers to the new food source once they have located it. These foragers will bring the food back to the nest to feed the colony, quickly consuming liquid-based foods themselves, while relying on larvae within the colony to process solid foods. Red imported fire ants will feed and forage for small insects, dead animals, and sources of sugars like plant secretions throughout their territory. Fire ants will forage up to roughly 80 yards from their mound — however, polygyne colonies sprawled throughout mounds can increase this range.

While in search of food, RIFA often find themselves overlapping with humans. This can occur inside residential and even commercial structures, like homes, offices, or schools. Or it can occur in nature, in areas frequented by individuals or groups for play, recreation, or business. This level of overlap can raise more concern for the risk of stings, which can lead to severe allergic response. Foraging ants underground have been known to cause agricultural damage to root vegetables and tubers like potatoes and peanuts. During periods of drought, ants can damage plant crops when searching for moisture.

The foraging strategies of RIFA are critical to management plans. Briefly, the preferences of RIFA shift based on the needs of the colony, time of day and year, and in fact can shift based on the prevalence of disease within the colony. All ant baits fall into one of two categories, either sugar-based or protein-based, and if the wrong one is applied at the wrong time, control efforts will fail. To read more about RIFA baiting strategies, check out our publication — Surveillance & Management of Red Imported Fire Ant (RIFA).

Mound Building

The RIFA mound is diagnostic for the species, meaning that no other ant in North Carolina builds similar mounds. They are characterized as large mounds of soil, rising above and among the low-lying vegetation in the areas they are built (Figure 5). They are typically built in open areas with lots of sun, like parks and pastures, though mounds can be built in just about any type of soil. Mounds that are made in clay soil are often symmetrical and rounded — taking on the traditional red coloration due to the clay — while mounds in sandy soils are irregularly shaped and beige to match. Sometimes, mounds can be built on rotting logs, in and around tree stumps, throughout landscaping materials, and within stonework. In fact, mounds can even be built within and around junction boxes, outlets, and electrical equipment — the ants being attracted to the electric current — and have even been known to damage these systems. The size of the mound is directly proportional to the size of the colony. Some larger mounds can have colonies with up to 500,000 workers! Mounds can have galleries and tunnels that extend up to 6 feet underground — a fun art project if you are so inclined!

The ants don’t just build large mounds to stand out, but rather, the mounds assist to regulate temperature, acting as air conditioners in the summer months and heaters during the winter. In fact, the season and time of day influence the location of the brood — pupae, larvae, and eggs — as higher in the mound is often warmer, while deeper is often cooler. The mound itself acts as a parabolic dish to capture heat from the sun and radiate it throughout the colony. Winged adults use mounds as landing platforms and beacons during flight. They also provide elevation for the colony to protect from floods during rain.

Ants will frequently migrate from mound to mound to start new colonies, sometimes several hundred feet away from the previous location. These “satellite” colonies can present challenges for pest management, as all queens must be killed to eliminate the infestation. When mounds are disturbed, their radial entrances allow for large numbers of workers to quickly emerge and aggressively defend themselves by stinging the intruder. It is important to note that while mounds are characteristics of RIFA, that does not mean that mounds are always present when there is a colony. New colonies will likely need to grow before a mound is constructed.

Communication & Defense

Ants communicate the vast majority of information within the colony through the use of pheromones — chemical signals designed specifically to communicate with members of the same species. Within the colony, pheromones can be direct tasks, and identify friends from foe. Larvae can also use pheromone signals to indicate needs to worker ants. Outside of the colony pheromones can be used to alert and guide other workers to a food source, as a beacon to ants attempting to locate the mound, and as an alarm signaling a need for defense of the colony. Commonly, ants are seen following a trail of pheromones that has been left behind leading to a food source and back to the nest. When a colony is disturbed, the threatened ants will release an alarm pheromone to signal to other ants to protect and defend the colony. Ants can also distinguish between familiar and strange ants through specific colony-associated pheromones.

In response to alarm pheromones, the RIFA workers will swarm the potential threat, latching on with their mandibles and stinging repeatedly. Each sting injects a caustic venom into the unlucky target. As with all eusocial stinging insects, pheromones associated with stinging elicit more stings from other members of the colony. There is a limited reservoir of venom in each ant, but with such immense numbers, the intruder can quickly experience allergic reactions to the large amount of injected venom.

Risks to Animals & Structures

The RIFA can pose a number of risks to a variety of animals, as well as potential risks to structures if left unmanaged. We cover the most common risks below:

Humans & Animals

By far, the greatest threat to humans and animals associated with RIFA infestation is the risk of stings and associated allergic response. Individuals may experience a mild reaction to stings initially, but over time, the allergic response can increase. The typical reaction to a sting is a red and swollen pustule, which develops a white head as it heals and can be incredibly itchy (Figure 6). Roughly ⅓ of the population living in areas with established RIFA populations are stung each year — with 2% of these stings resulting in a systemic allergic reaction. While this percentage is low, with such a high number of exposures per year, a decent number of individuals could experience some level of intense reaction.

These reactions can be worse in animals and pets, who often are first stung around the face due to disturbing the mound while smelling or feeding. This can lead to swelling of the respiratory system, nose, and mouth — increasing the risk of suffocation. There is also a vast ecological impact associated with infestation, as many lizards, amphibians, and even ground/low nesting birds can be targeted by hungry colonies as sources of food.

Structures

The major risk to structures associated with RIFA infestation centers around electrical systems — as mentioned above. The ants are attracted to electric currents, at times building directly inside of junction boxes, outdoor outlets, and other similar locations. As a result, the function of these can be greatly disrupted, leading to power outages and a need to repair or replace the affected equipment. Within structures, you may also see RIFA workers emerging from joints in the slab or from underneath flooring or carpet. In these instances, they may not necessarily damage the structure, but their expansion throughout the structure can greatly increase the risk of stings.

Publication date: Feb. 17, 2025

The use of brand names in this publication does not imply endorsement by NC State University or N.C. A&T State University of the products or services named nor discrimination against similar products or services not mentioned.

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.