Description and Biology

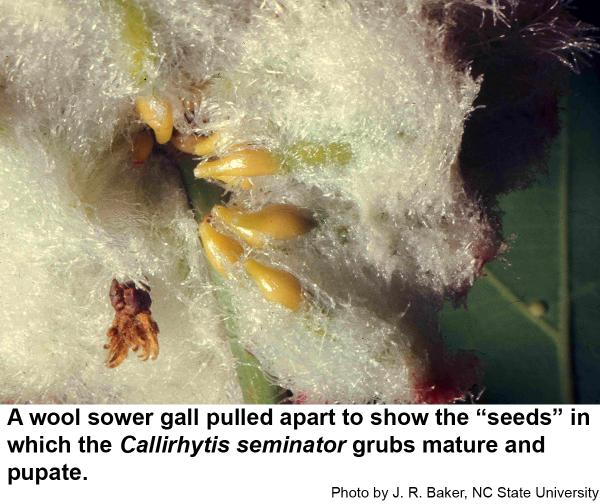

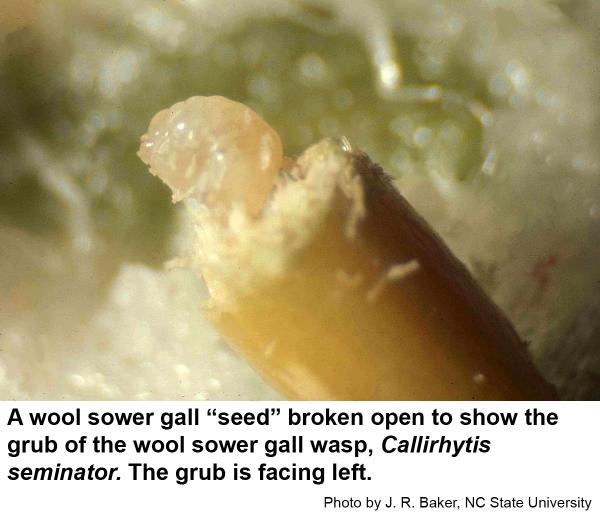

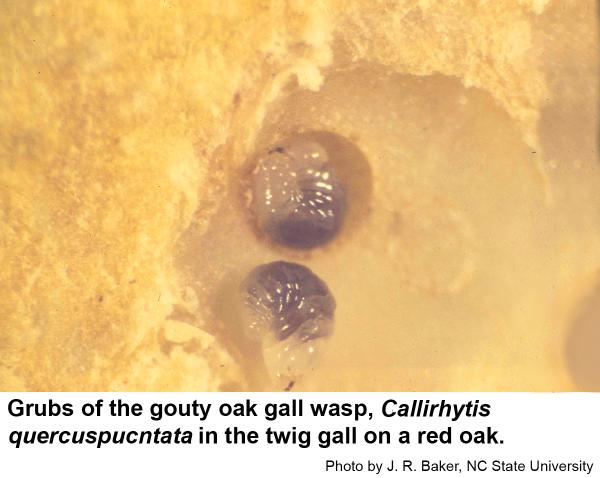

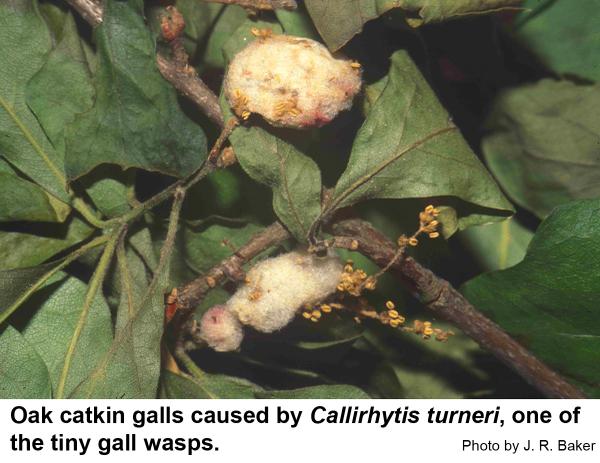

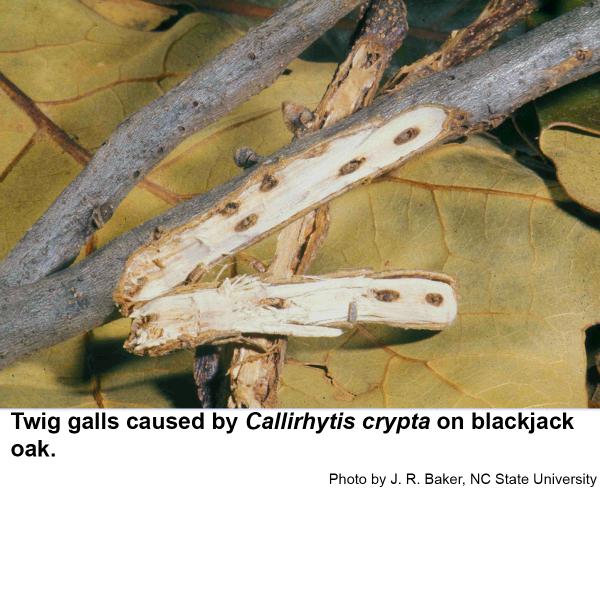

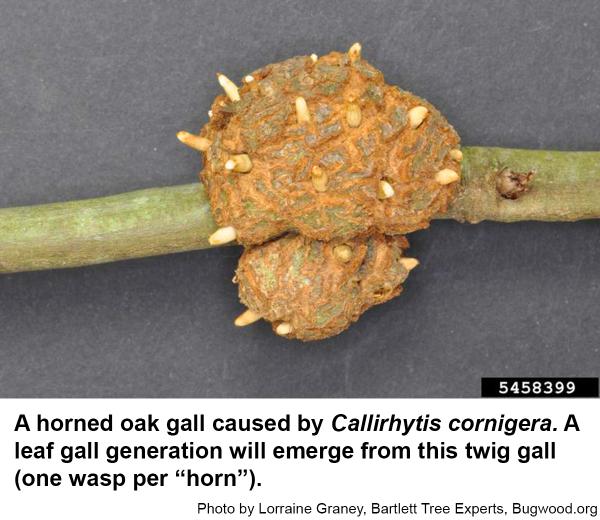

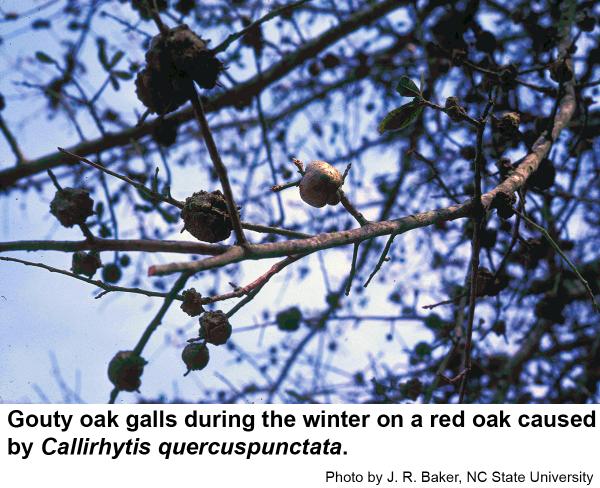

Callirhytis gall wasps are small (3/16 inch), brown, winged insects that have the abdomen flattened from side to side. The grubs are tiny, plump, white insects with heads that are lightly sclerotized. On older grubs, the gut contents give the grub a dark appearance. Many gall wasps develop for 2 or 3 years in woody galls on the twigs of oaks. Adults (all females!) then emerge from the twig galls during the winter and early spring. They lay eggs in the buds and die. When these eggs hatch, and new growth resumes on the oak, salivary secretions of the gall wasp grub act as powerful plant growth regulators and force leaves to form galls. Gall wasp galls typically have an outer wall, a spongy fiber layer and a hard, seed-like structure inside of which the gall wasp grub develops. Although gall wasp grubs have chewing mouthparts, they do not seem to chew plant tissue. Evidently the gall secretes nutrients that the grubs lap up. When grubs in the leaf galls mature, they pupate, and in a few weeks a new generation of male and female leaf gall adults chews out. These mate, and then females lay their eggs in oak twigs. Although most gall wasps are superficially similar, the adults from the leaf galls do not exactly resemble adults from twig galls. This is called alteration of generations in which the offspring resemble their grandparents rather than their parents.

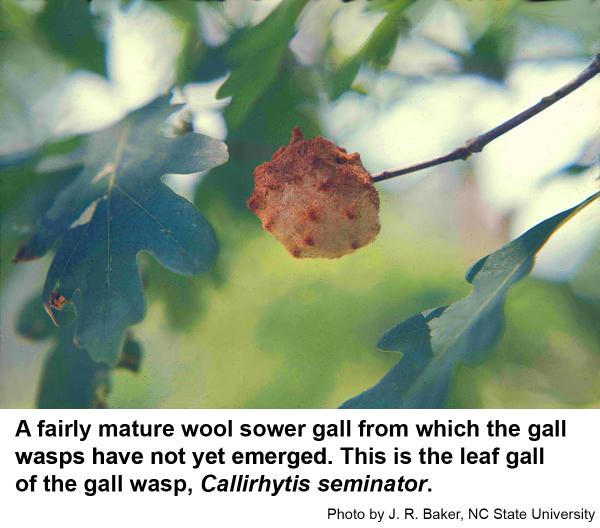

The wool sower gall is caused by secretions of grubs of Callirhytis seminator. The wool sower gall is the leaf gall generation that is specific to white oak and only occurs in the spring. The galls contain seed-like structures (This gall is also called the oak seed gall.). The gall wasps develop inside these structures. These wasps probably lay their eggs in midwinter and the eggs hatch just as the new growth emerges in spring. Wool sower gall wasps probably have an alternate generation that develops in twig galls.

Horned oak galls and gouty oak galls are caused by the twig generation of Callirhytis cornigera and Callirhytis quercuspunctata respectively. Twig galls have much more impact on the health of oaks than do leaf galls.

Host Plants

Callirhytis gall wasps infest the twigs and leaves of many species of oaks. For example, horned oak galls occur on Pin, Black, and Water Oak, whereas gouty oak galls occur on Pin, Scarlet, Red, and Black Oaks. Twig galls may eventually cause the stem to die from the gall outward. Heavily infested trees have considerable dieback and generally appear unthrifty because of all the galls on dead twigs. The death of heavily infested trees has been reported. Fortunately, wool sower galls and other leaf galls are usually never abundant enough to threaten the health of infested trees.

Residential Recommendations

Residential Recommendations

By the time twig galls are noticed, it is too late to effectively control the gall wasp grubs inside. Whether the gall wasps are causing tree decline or the declining health of a tree makes it attractive to gall wasps is a matter of conjecture. Because most heavily infested trees are obviously declining, it is a good idea to try to improve growing conditions for infested trees. A soil sample from under an infested tree should be submitted it to the NCDA Soils Lab. If the pH or nutrients are out of whack, the soil should be amended. (Don't just apply a bunch of 10-10-10. Excessive nitrogen is likely to make these and other pests worse.) During periods of prolonged drought stress the tree should be irrigated. "RoundUpping" the grass under the tree and mulching the soil will help conserve soil moisture and keep the roots somewhat cooler. In other words, anything within reason that can be done to enhance the vitality of the trees should be tried. It is known that trees under stress have more simple sugars (rather than starches) and more free amino acids (rather than more complex proteins) in their sap. Thus stressed trees are more nutritious to the gall wasps than healthy trees. By getting the tree into top growing condition, it should be less susceptible to the gall wasps and the gall wasps will not reproduce as prolifically. As a consequence, the gall wasp population may die away naturally. However, if the injury gets cumulatively worse over the next few years in spite of improving growing conditions, it may be worthwhile to treat with a systemic insecticide in late winter or no later than the new growth emergence in spring. Because these wasps have a leaf gall stage as well, treating with a systemic insecticide (such as imidacloprid) in late winter should disrupt their life cycle and after a year or so, numbers of new galls should decline (unless the wasps can fly in from a nearby infested oak).

References

- Common name: gall wasps, scientific name: Callirhytis quercusclaviger (Ashmead) and Callirhytis cornigera (Osten Sacken) (Insecta: Hymenoptera: Cynipidae). Dixon, W. N. 2015 (revised). Featured Creatures. Entomology & Nematology, FDACS/DPI, EDIS. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry. Publication Number: EENY-368.

- Common Oak Galls. Townsend, L. and E. Eliason. University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Food and Environment, Entomology at the University of Kentucky. ENTFACT-408.

- Galls on Oak. Hoover, G. A., Sr. 2013. PennState College of Agr. Sci. Dept. Entomology. Insect Advice from Extension.

- Galls on Oaks. Frank, S., J. R. Baker, and S. Bambara. 2002. Entomology Insect Notes, NC State Extension Publications.

- Oak Galls. Bratsch, T. and P. Nixon. 2007. Home, Yard & Garden Pest Newsletter, University of Illinois Extension.

- Extension Plant Pathology Publications and Factsheets

- Horticultural Science Publications

- North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual

For assistance with a specific problem, contact your local N.C. Cooperative Extension Center

This Factsheet has not been peer reviewed.

Publication date: July 29, 2016

Reviewed/Revised: June 3, 2021

Recommendations for the use of agricultural chemicals are included in this publication as a convenience to the reader. The use of brand names and any mention or listing of commercial products or services in this publication does not imply endorsement by NC State University or N.C. A&T State University nor discrimination against similar products or services not mentioned. Individuals who use agricultural chemicals are responsible for ensuring that the intended use complies with current regulations and conforms to the product label. Be sure to obtain current information about usage regulations and examine a current product label before applying any chemical. For assistance, contact your local N.C. Cooperative Extension county center.

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.