Introduction

Urban wood products have become a niche within the wood products community. Relatively new in the wood sector, urban wood businesses (UWBs) are attracting attention among consumers and company owners across the country. There is great market potential for UWBs that offer products with unique aesthetics, wood craftsmanship, an environmental conscience, and historical importance (such as the tree you climbed on as a child that has reached the end of its life).

A starting point in the history of urban wood is the emerald ash borer, which is an invasive bug whose larvae, the beetle, and its offspring can cause severe damage to trees. Larvae that feed off the cambium, the growth layer of trees, cause trees to die. Many major cities have cut down thousands of infected trees to stop the infestation. This crisis led to the development of numerous UWBs.

However, urban wood businesses can thrive easily without calamities and natural disasters. All trees that do not match industrial standards for the species, size, or location are of potential interest to the urban wood community. It is the craftsmanship that can convert an impressive tree into a unique product.

A major driver of UWBs is the amount of unrealized economic value in the underutilized urban wood resource. As shown in Table 1, the value of urban wood products varies by the raw materials, the complexity and length of production, and product quantity. Log seconds and thirds are generally low-value products because they require minimal processing for large quantities at low market values for individual pieces. In contrast, UWBs focus on unique, custom, higher-value products, which require a degree of craftsmanship (Pitti et al. 2020). However, the philosophy of the urban wood movement is to make the best use of all resources available. This means that many UWBs produce a variety of different products from different parts of the same tree, such as slabs, firewood, and mulch. The challenge is to produce the best combination of products from a sustainable resource and a market point of view.

Urban wood has experienced large growth during the last 15 years. According to a 2019 survey, only ⅓ of the urban wood companies in the survey were older than 15 years (Pitti et al. 2019). The survey included responses from 23 urban wood businesses in 14 states about the initial steps, challenges, and lessons learned when starting a UWB. The survey asked general questions about the businesses, factors that were important in the early days of their operation, and the factors that are important in the current business.

| Product | Raw Material | Processing Steps | Equipment | Quantity | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logs 3rds/2nds | Logs | Saw | Medium | Low | |

| Chips, low-quality | Trees and branches | Chipping, grinding | Chipper | High | Low |

| Compost | Trees, logs, organic material | Chipping, grinding | Chipper, skid steer | High | Low |

| Chips, high-quality | Trees and branches | Chipping, grinding | Chipper, skid steer | High | Medium |

| Pallets | Logs | Milling, kiln-drying, assembly | Saw, dry kiln, sander, assembly machines | Medium | Medium |

| Firewood | Logs or pieces of logs | Cutting, splitting, drying (sometimes phytosanitation) | Saw; log splitter | Medium | Medium |

| Lumber | Logs | Milling; air-drying, kiln-drying | Saw, dry kiln, planer, sander | Medium | High |

| Slabs | Logs | Milling; air-drying, kiln-drying | Saw, dry kiln, planer, sander | Low | High |

Adapted from Galvin et al. 2020.

Results and Discussion

Experience and Background

There is no typical background for those who start new UWBs. The founders are at different stages of their lives and some have no experience with wood products. A total of 11 of 23 survey participants indicated that they had no background in wood. Career changers often use their previously acquired talents and financial wealth to start a UWB at mid-career. Leaving a corporate environment to work with a natural resource in an independent environment is common. Financial resources ease some of the challenges of starting a UWB, while for some, processing urban wood often starts as a part-time activity or even a hobby. Fifteen of the 23 participants indicated that they started their business part-time and then transitioned to full-time operations as the business grew.

Early Stages

Establishing a sustainable and financially sound UWB comes with challenges, especially in the early stages. Processing a log into a product requires a series of steps that require both skills and equipment. Survey respondents identified market access and the continuity of sales as the biggest challenges they experienced during the early stages of the business. Table 2 shows that equipment-related skills, such as machine operation and maintenance, logistics, and material handling pose challenges. The use of equipment has a learning curve. The ability to learn new skills is important. Less costly, entry-level equipment requires a higher degree of manual intervention due to the lack of automatization and functionality. An example is the absence of a hydraulic loading mechanism to move logs onto a trailer or a saw. Space is also a problem, as are time and raw materials. The UWBs often start as a one-person operation in which long days and weeks can quickly become challenging and overwhelming.

| Early Challenge | Responses |

|---|---|

| Market access and continuity of sales | 8 |

| Machine operation and maintenance | 4 |

| Logistics and material handling | 3 |

| Space | 3 |

| Funding and finances | 3 |

| Time | 1 |

| Raw materials | 1 |

Urban Wood Business Model

Business models describe the different activities needed to generate business revenue. Table 3 provides an overview of a business model with the routine activities and tasks of a UWB. With small UWBs that employ just one or two employees, many tasks are managed and conducted by the same person. These UWBs require generalists with a broad range of skill sets.

| Components | Urban Wood Businesses |

|---|---|

| Main activities |

Processing logs into lumber by milling, air and kiln-drying, and planing/sanding Processing reclaimed wood Processing lumber into secondary products through woodworking Marketing and selling primary and secondary wood products to private and public customers or local carpenters Offering services for a fee |

| Source of materials |

Landscaping businesses, arborists, and tree services Wood from landowners or private residences Calamities, such as weather events or insects Clearings from construction and other developments Salvaged lumber from landfills Public utilities and municipalities |

| Main sales |

Direct revenue from wholesale primary products Direct revenue from custom projects Secondary products for individual customers Services such as milling and drying for clients |

| Initial funding |

Government grants, public donations, supportive cooperative partnerships, and (personal) wealth |

| Main expenses |

Start-up equipment such as sawmills, kilns, and transportation Materials and supplies to maintain equipment and tools Purchase or lease of space Raw materials Salaries for additional employees Marketing of services and products |

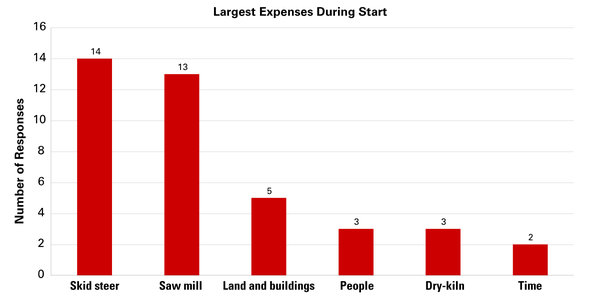

Initial funding can be challenging because several large investments are required to start the business. As shown in Figure 1, the two largest initial expenses are a skid steer loader for moving material and a sawmill for cutting lumber and slabs. Land and buildings are considered larger expenses than employees, dry kiln, and time. The cost of land and construction has increased significantly. Respondents referred to the need for additional employees and the scarcity of additional help in the early stages, which is often due to financial constraints and the challenges of finding skilled part-time employees. Entry-level dry kilns such as solar and RH kilns can be built relatively inexpensively or delayed when the focus is on milling services only.

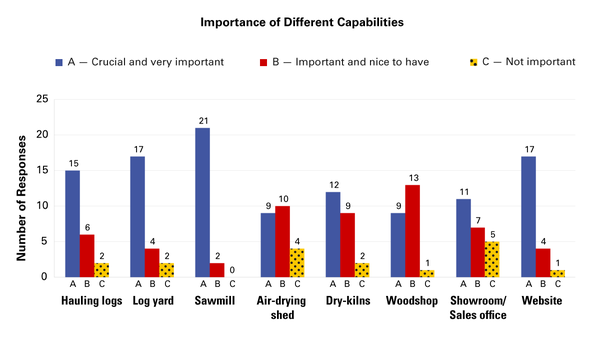

As shown in Figure 2, survey participants identified the ability to move logs, a log yard, and a sawmill as the most important capabilities of a UWB. A website was viewed as equally important as a log yard because it attracts customers. Other capabilities seen as less important were dry kilns, a woodshop, and a sales office. Air-drying sheds and a showroom/sales office were not considered as important.

To create a stable and reliable business, it is important to diversify the number of revenue streams. This includes offering a variety of different products, as well as services such as milling and drying. The four leading capabilities in Figure 3 (hauling logs, a log yard, a sawmill, and a website) can help generate revenue in the early stages of the business which can be reinvested later to expand the operation.

Examples of services include cutting trees; milling lumber, slabs, and cookies; air-drying; kiln-drying; planing and sanding; epoxy work; woodworking and furniture making; and storage.

Carpenters with a focus on the end product may source kiln-dried lumber from their local UWB. Hobbyists might have the capabilities to pursue some woodworking in their garage, but may lack the skills and technologies to mill an entire log.

Developing additional revenue streams can be vital to a business, and it is crucial to take the proper precautions. Drying wood, for example, comes with a high degree of responsibility. If the wood develops defects or is improperly dried, the liability may be borne by the UWB that provided the service. Many drying defects are irreversible. Liability waivers are one solution to overcome potential issues.

Although the UWBs primary purpose is the generation of profit through direct sales and services, the urban wood philosophy entails valuing and supporting the surrounding local communities. This is the case with wood banks, a public site where wood is dried, processed into firewood, and made available for public and private use (Vivian and Leahy 2015). The wood is often sourced for free or donated to alleviate the cost of heating in local communities. A local UWB can provide oversight and technical expertise. Similar to the concept of a cooperative, cost and labor are supported by local groups and the community. This concept has been implemented with firewood and may be expanded to other types of primary processing such as lumber, slabs, and mulch. This could be conducted at a municipal level to reduce the overall tipping fees for surrounding tree companies and to generate a local economic impact.

Urban Wood Business Strategies

Despite the overarching need to recognize and use the neglected value of urban wood resources, urban wood operations are businesses that must manage profits and losses to sustain themselves and grow. The businesses also have responsibilities to their employees and the maintenance of equipment.

What sometimes begins as an opportunity to salvage some lumber from an urban tree can quickly turn into a long chain of processes with the final goal of selling a product. In many cases, the excitement for urban wood and creating something begins as a hobby, with little to no financial interest. Some UWBs do not pay for their logs although transportation of the logs to the UWB site requires labor and transportation. As a one-time opportunity of salvaging an urban tree turns into a regular business with desired successful outcomes, the operation must follow a strategic business model that supports the mission of the operation.

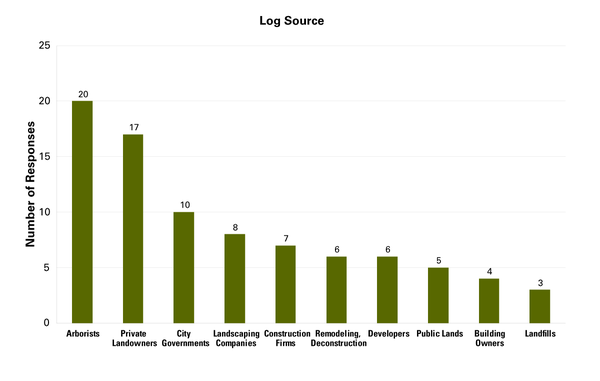

Raw Material Sourcing

It is true that UWBs benefit from an abundance of free logs. In reality, however, not all wood is free. Certain species, dimensions, and logs with a story come with a cost. The majority of survey participants indicated they always (6) and sometimes (8) pay for their logs. The responses in Figure 3 show that arborists, private landowners, and city governments are among the most common sources of logs. Arborists and city governments frequently have access to large amounts of logs and a financial interest in additional business or the avoidance of tipping fees. In some areas, logs are available

from clearing and developments, although landfills are a very limited source.

Trees should be graded for potential use and inventoried before cutting and harvesting. Standing tree inventories, harvesting plans, and work orders are ideal tools for predicting future resources. Availability and access to such information can vary. Local municipalities and resources within the business network can be helpful in retrieving information and predicting the future inflow of raw materials, and the actual availability of logs.

Log Sorting Yard

The standardized grading of logs in the hardwood industry requires the skill to reliably predict the products contained in an urban log and make correct assumptions about the value based on the expected revenue. In the sorting yard, logs and tree sections are dumped onto a large pile, and then sorted by criteria such as log origin, dimensions, species, and end-uses. Some species benefit from wet storage with the continuous application of water spray to protect against insects and bacterial attacks. This technology, however, is used rarely in UWBs.

Arborists who operate an UWB must strategically limit the inflow of trees into the urban wood side of their company. There is often an overabundance of incoming logs and stumps and not all can be processed into the same high-value products.

Even small operations can benefit from collecting sufficient quantities to overcome certain thresholds. Processes such as sawing and drying can become more efficient by accumulating and then processing logs with common characteristics. The same applies to low-value, high-quantity products such as firewood.

Logs with a recognizable, valuable history must be kept separately. A yard-wide inventory system must be maintained to retain the added value of the logs’ history. Many companies have developed manual and digital tagging systems to manage their inventory.

Milling and Woodworking

The sawmill is the most important tool of any UWB. Sawmills require a comparably large investment at the initial stage of the business. A critical aspect, which is often fully understood in hindsight, is the size and functionality of the sawmill. A saw that is too narrow limits the maximum width of slabs and the overall profit of the log.

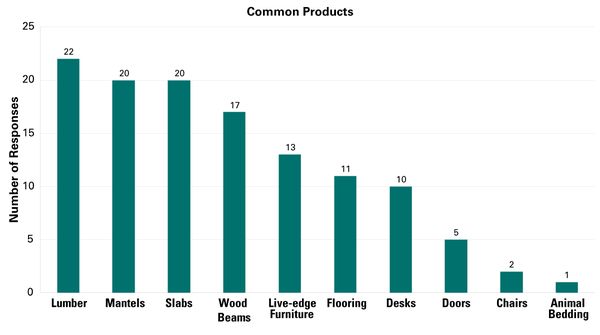

As shown in Figure 4, the survey identified lumber, slabs, mantels, and beams as the most commonly produced urban wood products. Products that require a higher degree of processing and skills were less frequently cited by respondents because some companies focus only on primary processing.

Marketing and Sales

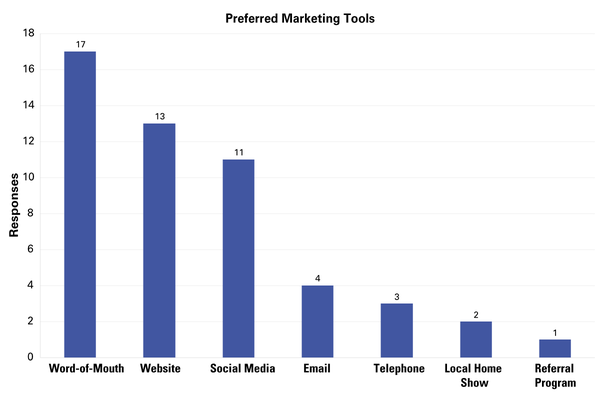

Word-of-mouth within a network of contacts is the primary path through which UWBs market their products. According to a 2019 study, public relations and social media are among the most important marketing venues for reaching new and existing customers (Espinoza and Pitti 2019). The importance of online tools such as websites, social media, and email was confirmed through the survey. Figure 5 shows that online marketing tools were selected 28 times. However, the survey confirmed word-of- mouth as the most important marketing tool with 17 responses. (Some participants selected multiple responses.) Social media is typically used for product ads, updates about sales events, and workshops. A company website acts as a virtual storefront to provide information about the business, contact forms, and an online store.

In general, UWBs focus a great deal of effort into developing, cultivating, and maintaining a strong brand. The brand includes the company name, company origin, the company’s story, values, logo, and color scheme. All are reflected in the brand messaging of the UWB. The goal is to present unique products and services that distinguish the business from the competition, other UWBs, and the commodity industry. The collective goal is helping the business thrive by offering clients a unique service expressed through the brand.

“Quality, aesthetics, customization, and sustainability are the most important marketing messages for urban wood” (Espinoza and Pitti 2019).

Marketing also includes building a wide network to overcome inventory and capacity limitations. This may involve finding additional drying capacity and acquiring specific species and dimensions. The ability to successfully refer a customer to another UWB increases the use of unused resources, the marketability of products and services, and the overall perception of customer service in the industry. Both the network and customer base will grow stronger. Informal partnerships with surrounding businesses increase the identification of new clients. Memberships in regional and national associations also help to increase the presence and visibility of the business to customers and stakeholders along the chain of processing.

Sustainability and Chain of Custody

Sustainability and a transparent chain of custody are important marketing themes in urban wood, which was founded on the concept of turning an abundance of underutilized wood resources into marketable products, Thus, it is traditional for UWBs to incorporate sustainability as a marketing tool. The sustainable nature of urban wood is a recurring theme on websites, in brochures, and during conversations with customers. The chain of custody documents the origin and subsequent handling steps of materials prior to the consumer’s ownership. For sustainable urban wood products, the chain of custody includes the harvesting locations, transportation, the chain of processing, and sales.

Urban wood products offer unique assets that are not found in commodity items. The products come in many shapes and sizes, have historical significance to individuals or communities, and contain distinctive features not found elsewhere. Crafting the narrative is equally important as manufacturing an appealing item to successfully promote sustainable products.

Selling Products - Online vs. Showroom

Urban wood products are generally sold through direct, retail, and online sales, which are the most frequently utilized distribution methods (Pitti et. al. 2020). A showroom with a representative selection of slabs and centerpieces is often the centerpiece of many UWBs. However, creating a rustic environment to showcase the products is important and does not require a lot of effort because of the down-to-earth nature of urban wood. A dedicated corner in the woodshop can easily showcase the products.

Many companies have created online catalogues to showcase and sell their products. These catalogues are often integrated into digital inventory systems that track product information. A portfolio of recent projects is also a very valuable strategy for demonstrating the company’s capabilities, skills, and products.

Social media has become an important component of urban wood marketing. The most successful UWBs typically have an up-to-date presence on social media to showcase their products, activities, and events. Eye-catching images or videos gain the attention of potential customers who are browsing their media feeds. Paid advertising that increases the number of reachable users is also a common form of marketing on social media.

Conclusion

Starting a UWB comes with various challenges. The famous “jack of all trades” has to step in from the beginning to help the business stabilize, grow, and move forward. There is no perfect recipe for successfully launching a UWB operation, although the research cited in this article confirmed that some strategies are more common. The most important investments were transportation and the purchase of a saw. For marketing, a website and social media are essential in successful businesses. The overall commonality among all UWBs is networking that builds and sustains strong relationships with suppliers, clients, and competitors.

References

Espinoza, Omar and Anna Pitti. “Marketing of Urban and Reclaimed Wood Products.” Presentation at the 7th International Scientific Conference on Hardwood Processing (ISCIP), Delft, The Netherlands, August 27-31, 2019.

Galvin, Mike, J. Morgan Groves, Sarah J. Hines, and Lauren Marshall. 2020. The Urban Wood Workbook: A Framework for the Baltimore Wood Project. Madison: USDA Forest Service.

Pitti, Anna, Oscar Espinoza, and Robert Smith. 2020. “The Case for Urban and Reclaimed Wood in the Circular Economy.” BioResources 15, no 3: 5226-5245.

Pitti, Anna, Oscar Espinoza, and Robert Smith. 2019. “Marketing Practices in the Urban Reclaimed Wood Industries.” BioProducts Business 4, no. 2: 15-26.

Vivian, Sabina and Jessica Leahy. 2015. A Community Guide to Starting & Running a Wood Bank. Orono, Maine: School of Forest Resources, University of Maine.

Publication date: March 10, 2023

AG-941

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.