Like other perennial plants, mature grapevines have extensive root systems and therefore, unlike shallow-rooted annual plants, they are fairly tolerant of mild droughts. Nevertheless, a certain amount of moisture is necessary to support growth and development. Lacking sufficient moisture, vines will suffer water stress, which can reduce productivity as well as fruit quality. Supplemental moisture can be provided by permanent (solid-set) or temporary irrigation systems. Drip irrigation has become the standard water delivery system for North Carolina vineyards in recent years. Drip irrigation can represent a substantial investment (see chapter 2 for details), but the benefits can far outweigh the costs in many vineyards. In 2005, it was estimated that drip irrigation would cost $22,743 to purchase and install the equipment required for a 10-acre drip system, or $2,274 per acre. Drip irrigation can be as effective on steep slopes as on rolling and flat surfaces.

The Vineyard Hydrologic Cycle

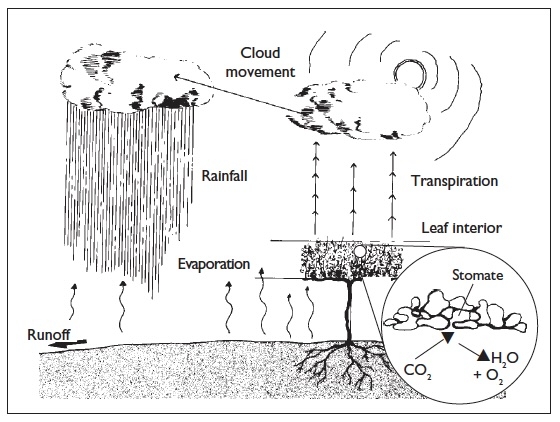

Water enters the vineyard as rainfall (Figure 10.1) or through irrigation. Some of this moisture drains out of the root zone into deeper soil layers and some runs off the soil surface. Water that remains in the root zone is available for absorption by the vine roots. A vineyard soil at field capacity (the amount of water that the soil can hold after gravitational drainage occurs) will lose moisture in two principal ways: through direct evaporation into the atmosphere and by transpiration from the leaves of the vines and any ground cover (Figure 10.1). Water moves out of the leaves through stomata, the small pores that admit carbon dioxide and release water vapor and oxygen. Collectively, transpiration and evaporation are referred to as evapotranspiration.

Summer Climate and the Potential for Drought

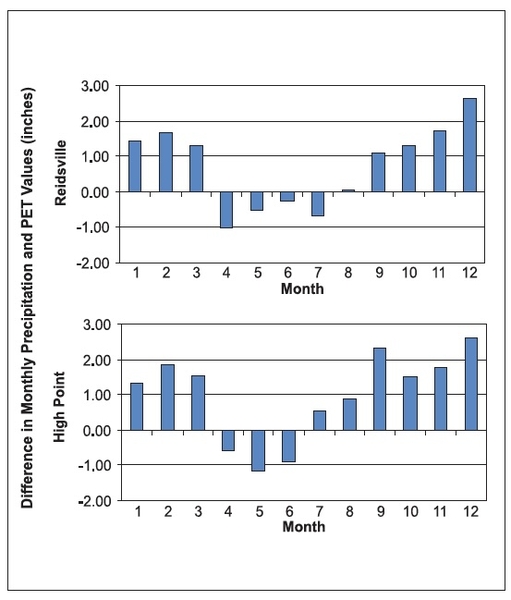

Agricultural meteorologists and climatologists use the expression potential evapotranspiration, or PET, to compare the water loss potential of different regions. PET, expressed in inches of water per unit of time, is a measure of how much evapotranspiration should occur from a moist surface. Evapotranspiration rates for vineyards vary according to the development of the vine canopy, presence or absence of ground cover, cultivation, and atmospheric conditions. Monthly precipitation is less than PET losses during summer months for most North Carolina locations. Figure 10.2 illustrates the imbalance between precipitation and PET values for two North Carolina locations. Note the water deficits that occur at those stations during the summer months. Averaged across all of North Carolina's State Climatic Weather stations, PET values exceed rainfall by an average of 1.5 inches during July.

Precipitation records indicate that most North Carolina weather stations record between 40 and 60 inches of precipitation per year. However, those annual averages do not reflect the frequency of rainfall. Even monthly precipitation averages can give a misleading impression of moisture availability. Summer precipitation in this region often results from thunderstorms. Those storms are usually restricted to small areas, and significant precipitation might cover only a 10- to 50-square-mile area. Furthermore, because rainfall during thunderstorms is intense, less water is absorbed by the soil than if an equal amount of precipitation fell over a longer period. Thus, infrequent summer downpours may not satisfy the vines’ critical need for moisture that would develop during extended hot, dry periods. Given high PET rates and the spotty nature of summer precipitation, summer droughts are not uncommon in this region. Consequently, irrigation may be of benefit at certain times during every growing season.

The Role of Water in the Vine

To an extent, all physiological processes in the plant are dependent upon water. In the larger scheme of plant processes, water plays a pivotal role in driving growth. The cells of adequately watered vines exert an outward pressure, which is termed turgor pressure. This pressure causes cell enlargement, which in turn leads to an increase in tissue and organ size, such as the lengthening of shoots. The lack of cell turgor pressure results in a flaccid or wilted appearance. Wilting occurs when the transpiration rates of leaves exceeds the ability of the vine to absorb water from the soil and conduct it to the leaves.

Symptoms of Water Stress

One of the first signs of drought is a change in the appearance of the vines. Rapidly growing shoot tips of well-watered vines appear soft and yellowish or reddish green. If large portions of the soil become dry, the rate of shoot growth slows and the shoot tips gradually become more grayish green, like the mature leaves. Tendril drying and abscission is also a useful early indicator of vine water stress. As water stress continues, leaves appear wilted, particularly during midday heat. Under prolonged and severe stress, leaves curl, brown, and eventually drop. Vines that suffer severe water stress begin to defoliate, exposing more of the fruit that had been shaded by foliage. Depending on the time and severity of water shortage, berries of stressed vines may not attain their full size. Water-stressed fruit exposed to the sun can sunburn and shrivel, much like a raisin. Water shortages also reduce the vine’s ability to absorb nutrients from the soil. Symptoms of nutrient deficiencies are therefore more apparent during prolonged dry periods.

In addition to visual indicators, vine water stress can be measured with special instruments. Some instruments measure the water status of vines, whereas others measure the moisture status of the soil. Hand-held infrared thermometers can measure the temperature of vine canopies. The leaves of water-stressed vines are often warmer than the surrounding air because of reduced transpirational cooling. Leaves of well-watered vines are generally cooler than the air, even during the hottest period of the day. The moisture status of the soil can be determined with instruments that range from simple tensiometers to sophisticated neutron probes. The use and merit of various soil moisture sensors are reviewed by Coggan (2002) and Selker and Baer (2002).

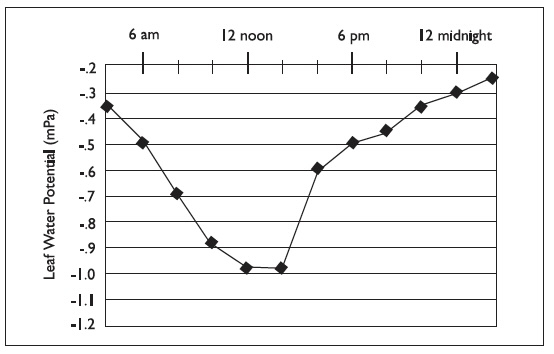

The water status of vines can also be measured by determining how much pressure is required to force water from a detached leaf. A wilted leaf will hold its remaining moisture with more tension (negative pressure) than will a fully hydrated leaf. The tension with which a leaf holds water is expressed in units of negative pressure called milliPascals (mPa). Figure 10.3 shows the changes in leaf water potential throughout the course of a day. The more negative the value, the more stressed the leaf is.

Leaf water potentials become more negative throughout the course of a day as the leaves lose moisture. The leaf water potential is generally most negative during the hottest part of the day and then decreases (becomes less negative) as vines regain their hydrated status in the cool of the night (Figure 10.3). When leaf water potentials reach about -1.2 mPa, stomata close. This closure conserves the remaining water in the leaf, but the “cost” of this water conservation is decreased sugar production. With stomata closed, carbon dioxide cannot enter the leaf and the photosynthetic conversion of carbon dioxide into sugars will not occur.

Extended periods of drought prevent the vine from regaining its hydrated status. Dehydrated leaves remain at or below -1.2 mPa for much of the day, and consequently photosynthesis is greatly reduced. The impairment of the photosynthetic processes will generally occur before leaves are visibly wilted. Reduced photosynthesis can explain why fruit fails to increase in soluble solids during periods of water shortage; little or no sugar is being manufactured. A point will be reached at which the daily stress of insufficient water will have an irreversible impact on the vine’s performance. By the time leaf wilting occurs, vines are severely stressed.

Many processes are disturbed or impaired by water stress. The impairment of those processes depends on the severity of stress and can be characterized as either reversible or irreversible. Reversible effects include

-

decreased cell turgor pressure

-

reduced stomatal conductance (that is, less carbon dioxide enters the leaf)

-

reduced photosynthesis (sugar production)

-

decreased shoot growth rate

-

reduced berry size.

These events are “normal” occurrences in the day-to-day cycle of growth and development even of adequately watered vines. As water stress intensifies, however, irreversible effects become apparent. These effects, in order of increasing water stress and severity, include

-

irreversible reduction in berry size

-

decreased fruit set

-

delayed sugar accumulation in fruit

-

reduced bud fruitfulness in the subsequent year

-

reduced fruit coloration

-

leaf chlorosis (yellowing) and eventual burning

-

berry shriveling

-

reduced wood maturation and possibly reduced vine cold hardiness

-

defoliation

-

vine death

Delayed sugar accumulation and reduced bud fruitulness are of special interest because their occurrence is variable. Slight water stress can actually hasten sugar accumulation and increase bud fruitfulness by causing a somewhat more open or light-porous canopy. Exposed fruit tends to accumulate sugar at a faster rate than does shaded fruit. Furthermore, slowed vegetative growth reduces the “sink” strength of shoots and roots. Thus, more of the vine’s carbohydrates are directed to fruit “sinks.” Slight water stress, therefore, might result in hastened fruit maturation.

However, excessive water stress can impair photosynthesis and fruit sugar accumulation. Buds exposed to sunlight during their development are more fruitful than those that are shaded. However, severe water stress reduces the fruitfulness of developing buds and thus reduces crop yields in the subsequent season. Thus, irrigation should supply no more water than is needed to maintain adequate vegetative growth and berry development.

Water use increases in proportion to the leaf area of the vine. Large vines require more water than do small vines. However, water stress is usually more severe in a young vineyard because the young vines have less-well-developed root systems and cannot draw moisture from as large a volume of soil as can large vines. Thus, the best time to install an irrigation system in the vineyard is at or before the time it is established.

Finally, the presence or absence of weeds and cover crops also affects the vines’ need for supplemental water. Cover crops compete with the vines for water. This competition can be minimized by keeping the cover crop mowed short or by using cover crops that become dormant during hot, dry weather. Weeds also compete with vines for critical moisture. Weeds should be excluded from the area under the trellis by mechanical or chemical means. Irrigation should never be used as a remedy for poor weed control. The elimination of weeds might go far towards alleviating the vines’ water stress, as discussed in the chapter 8 section on vineyard floor management.

Irrigation Systems

A properly functioning irrigation system ensures that vines have adequate moisture. As stated earlier, the objective of irrigation is to supplement natural precipitation so that vines achieve adequate vegetative growth and berry development. Vineyards can be equipped with a sprinkler, drip, or trickle irrigation system; each has its particular advantages and disadvantages. A drip irrigation system uses lightweight plastic tubing and fittings to make frequent applications of small amounts of water directly to the plant root zone. Drip irrigation is generally preferred over sprinkler irrigation for these reasons:

- less water is used (1/3 to 1/2 less with proper management)

- less energy is required because less water is delivered at lower operating pressures

-

leaves remain dry during irrigation, reducing the incidence of disease

-

the solid-set nature of the drip system results in lower labor and operating costs

-

field operations can continue while irrigating

-

the need to control weeds or to cultivate and mow between rows is reduced

-

less fertilizer is needed if it is injected directly into the irrigation water

-

less runoff occurs on hilly terrain, reducing soil erosion

-

no wind interference occurs

-

the system can be easily automated. Drip irrigation systems also have several disadvantages:

-

system components can be damaged by insects, rodents, and laborers

-

the small emission orifices may be easily clogged

-

the system offers no frost protection

Drip irrigation systems are similar to sprinkler irrigation systems in that they require a pumping station to deliver water, a main line to move water from the source to the vineyard, submains to distribute water throughout the vineyard, and laterals with emitters, which replace the sprinklers. The lateral tubing and emitters may be suspended from a trellis wire, laid directly on the ground, or buried in the root zone of the vines.

Water Supplies

The primary difference between drip irrigation and sprinkler irrigation systems is the consideration that must be given to water quality with drip irrigation. Particulate matter such as sand, silt, and algae can easily clog the small orifices of emitters. Therefore, a water filtration system must be installed between the pumping station and the vineyard. For groundwater supplies such as wells and protected springs, an inexpensive screen filter is usually adequate. When streams or ponds are used, sand media filters are recommended. Sand filtration systems designed for drip irrigation are relatively expensive. For small systems, however, standard swimming pool filters may be substituted. The use of self-flushing emitters is highly recommended if the water quality is questionable. When water is of extremely low quality, microsprinklers, another form of low-volume, low-pressure irrigation, should be considered. The water quality of the potential water source should be analyzed before any substantial expenditures are made for an irrigation system. Contact your county Extension agent or regional agronomist for further information on water testing services available from the Agronomic Division of the NCDA & CS. Additional tests should be requested if specific contaminants are suspected. Water sources with little or no recharge should contain from 6 to 9 acre-inches of water for each acre to be irrigated during the season (1 acre inch equals 27,152 gallons). Sources such as streams or wells will need to yield 5 to 10 gallons per minute for each acre irrigated at a time. Zones smaller than 1 acre might be possible for smaller systems, thereby requiring even lower flow rates.

Soils

Any soil suitable for vineyard establishment can accommodate a drip irrigation system. Since water is applied slowly, even soils with very limited infiltration properties are not a deterrent to the use of drip irrigation. The major soil consideration is that of lateral water movement. Generally, in a light-textured, sandy soil water will move primarily downward, whereas in heavy-textured, clayey soils water will tend to move laterally outward from the emitter. In the former case, more emitters per vine may be required to thoroughly wet the root zone.

Terrain

The terrain, or topography, of the vineyard must also be considered. If designed properly, drip irrigation systems can be used on relatively steep slopes. In such applications, the use of pressure-compensating emitters are recommended. Whenever practical, vineyard rows should be laid out along the contour to minimize elevation changes along drip irrigation laterals and to minimize erosion associated with rain.

Pumps

Pumps for drip irrigation systems are considerably smaller than those for comparable sprinkler systems because the required flow rates and pressures are lower. Because the pressure is low, it is sometimes possible to use gravity feed from an elevated tank or reservoir. The major advantage of the smaller pumping unit requirement is that single-phase electric motors (under 7.5 horsepower) may be used to drive the pump in many cases. Electric pumping units are widely preferred for irrigation systems of this size and are well-suited to automatic control.

Injection Systems

Provision should be made for injection of fertilizer and chemicals into the irrigation water. Fertilizer efficiency can be greatly enhanced if the fertilizer is applied in this manner. In drip irrigation systems, an injection system is particularly helpful for introducing chlorine for algae control or acid for removal of bacterial slime or precipitated materials such as iron. Care must be taken to prevent environmental damage from accidental spills. It is required in North Carolina that safety equipment installed to prevent backflow of chemicals into the water source or chemical storage tank include some or all of the following, depending upon the method of injection: check valve, backflow preventer, vacuum breaker, low-pressure drain, and a power supply interconnected between irrigation pump and injector. In addition, proper installation calls for the use of corrosion-resistant components and injection away from water sources.

Water Management

Good water management is critical for proper drip irrigation operation. Tensiometers or electrical resistance blocks can be placed directly in the row to monitor the soil moisture conditions in the root zone of the vines. These “sensors” can be used to control pumping stations for fully automatic control of the irrigation system.

System Design

Because of the complexity of drip irrigation systems and the number of variables involved, consultation with an irrigation design professional is highly recommended. If you are interested in drip irrigation, discuss your needs with reputable companies that specialize in irrigation system design, installation, and maintenance. These companies often advertise in trade publications and exhibit their systems at trade shows. For more information, contact your county Cooperative Extension agent.

Drip Irrigation Suppliers

Some full-service drip irrigation dealers serving the region are:

Berry Hill Irrigation

3744 Hwy 58

Buffalo Junction, VA 24529

1-800-345-3747

Gra-Mac Irrigation

2310 NC Hwy 801 N.

Mocksville, NC 27028

1-800-422-35600

Johnsons & Company

PO Box 122 Advance, NC 276006

1-800-222-2691

henry.johnson@johnsonandcompanyirrigation.com

Mid-Atlantic Irrigation Company

PO Box L, Farmville, VA 23901

434-392-3141

References

Coggan, M. 2002. Water measurement in soil and vines, Vineyard and Winery Management. May/June, 43-53.

Fereres, E. (Ed.). 1981. Drip Irrigation Management. University of California Division of Agricultural Sciences, Leaflet No. 21,259. 39 pp.

Neja, R. A. 1982. How to Appraise Soil Physical Factors for Irrigated Vineyards. University of California Division of Agricultural Sciences, Leaflet No. 2,946. 20 pp.

Kasimatis, A. N. 1981. Vineyard Irrigation. University of California Division of Agricultural Sciences, Leaflet No. 2,823. 9 pp.

Selker, J., and E. Baer. 2002. An engineer’s approach to irrigation management in Oregon Pinot noir. Oregon Wine Advisory Board, OSU Winegrape Research Progress Reports 2001-2002. Oregon State University Agricultural Experiment Station, Corvallis.

Publication date: Feb. 28, 2007

Reviewed/Revised: Aug. 11, 2025

Other Publications in The North Carolina Winegrape Grower’s Guide

- Chapter 1. Introduction

- Chapter 2. Cost and Investment Analysis of Chardonnay (Vitis Vinifera) Winegrapes in North Carolina

- Chapter 3. Choice of Varieties

- Chapter 4. Vineyard Site Selection

- Chapter 5. Vineyard Establishment

- Chapter 6. Pruning and Training

- Chapter 7. Canopy Management

- Chapter 8. Pest Management

- Chapter 9. Vine Nutrition

- Chapter 10. Grapevine Water Relations and Vineyard Irrigation

- Chapter 11. Spring Frost Control

- Chapter 12. Crop Prediction

- Chapter 13. Appendix Contact Information

- Chapter 14. Glossary

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.