Introduction

High-quality wines — those that command premium prices — can be produced only from high-quality grapes. Grape quality can be defined in various ways, but ripeness and freedom from rots are two of the chief qualities. Producing ripe fruit with minimum rot and maximum varietal character is not easy in North Carolina. As described elsewhere in this publication, the combination of climate, soils, and vine vigor often leads to excessive vegetative growth. For reasons that will be discussed, luxurious vegetative growth can reduce vine fruitfulness, decrease varietal character, degrade other components of fruit quality, and hamper efforts at disease control. Canopy management practices can help alleviate these problems.

Canopy management is a broad term used to describe both proactive and remedial measures that can be taken to improve grapevine canopy characteristics. In the broadest sense, canopy management can entail decisions regarding row and vine spacing, choice of rootstock, training and pruning practices, irrigation, fertilization, and summer activities such as shoot hedging, shoot thinning, and selective leaf removal.

This chapter presents grapevine canopy management principles and describes management practices that have been used successfully to enhance fruit and wine quality. Several excellent references on canopy management are cited at the end of the chapter, including the very informative text Sunlight into Wine.

Grapevine Canopies

The grapevine canopy is defined by the shoot system of the vine, including stems, leaves, and fruit (Figure 7.1). As described in chapter 6, vines can be trained to a single-canopy system (such as the bilateral cordon system) or to a divided-canopy system (such as the open lyre). And, just as cane pruning weights can be used as a quantitative measure of vine vigor (chapter 6), canopies can be described by various measures. We can, for example, measure them by their height, width, exposed leaf surface area, number of leaf layers, and shoot density (the number of shoots per unit length of canopy). These measures can then be compared to ideal canopy dimensions to decide whether corrective action is warranted.

Canopy Microclimate

The reasons behind many recommended canopy management practices can be better understood by recognizing that heavy, dense grapevine canopies can create a highly localized climate, distinctly different from that immediately outside the canopy. The climate within the canopy is referred to as the canopy microclimate. It is described in familiar terms such as temperature, humidity, wind speed, and amount of sunlight. Table 7.1 compares the microclimate of a sparse canopy or the region outside of a canopy with the microclimate inside a dense canopy.

Considerable progress has been made in understanding how grapevine canopies create unique microclimates that, in turn, affect vine and fruit physiology.

Radiation

Grapevine leaves absorb approximately 90 percent of the sunlight that strikes them. This sunlight is responsible for photosynthesis, the process by which green plants convert sunlight and carbon dioxide into sugars and other carbohydrates. The exterior leaves of the canopy absorb large amounts of sunlight but transmit very little to the leaves deeper within the canopy. Shaded leaves are often not photosynthetically productive because they receive less sunlight than they need to produce carbohydrates. In addition, shaded leaves may contribute excess potassium to developing fruit and impede ventilation in the fruit zone. Excess potassium can, under certain conditions, contribute to elevated fruit acidity, which can be undesirable for making wine. Shade also reduces the fruitfulness of developing buds. Thus, yields from vines with dense canopies can be significantly lower than those from vines having a sparser shoot distribution.

Temperature

The air temperature within a grapevine canopy does not differ greatly from the temperature immediately outside the canopy. However, the shade produced by the exterior leaves can affect the radiational heating and cooling of fruit and leaves. For example, fully exposed fruit can be heated by solar radiation to a temperature 20° to 30°F higher than that of the surrounding air. That warming can be used to advantage in cool grape regions to reduce fruit acidity. Conversely, on clear nights, exposed fruit and leaves can cool as much as several degrees below the ambient air temperature by radiational cooling.

Wind Speed

Vine canopies reduce wind speed. The reduction is greater for dense canopies than for sparse ones. Wind movement — even a slight breeze — is very helpful in reducing fungal infections of fruit and leaves. Many of the fungi that attack grapevines in the eastern United States require either the presence of free water or a period of high humidity to infect the plant. Air movement helps evaporate moisture and reduce humidity in the canopy, reducing the opportunity for fungal infections to occur. Furthermore, sparse canopies permit greater pesticide penetration and coverage when vines are sprayed. The combined benefits of increased ventilation and increased pesticide penetration are fundamental reasons for using canopy management practices that promote a uniformly sparse or open canopy.

Principles of Canopy Management

Richard Smart, who advanced our knowledge of the relationship between canopy characteristics and fruit and wine quality, has provided a convenient means of understanding canopy management by condensing the underlying research findings into five basic principles. Those principles are reviewed here in a slightly modified form to provide a basis for recommendations on assessing and modifying canopy characteristics.

Principle 1: Vines should be spaced and trained to maximize the amount of leaf area exposed to sunlight. Furthermore, the canopy leaf area should develop rapidly in the spring. Principle 1 is derived from the observation that vineyard productivity increases when the percentage of available sunlight intercepted by vine leaves (rather than by the vineyard floor) increases. In essence, sunlight that falls on the vineyard floor is wasted. Studies have shown that grapevines receive the most sunlight when the vineyard rows are spaced fairly close and are oriented in a north-south direction. The canopies should be trained vertically to tall, thin curtains of foliage. Rapid leaf area development is promoted by retaining a relatively large number of short shoots on each vine, as opposed to a relatively few long shoots.

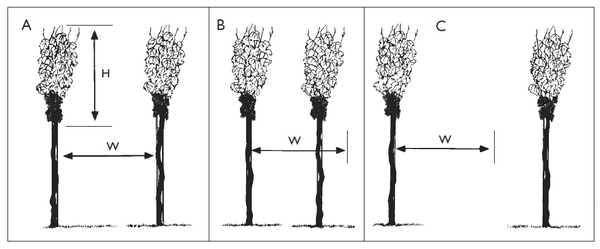

Principle 2: Rows and canopies should not be so closely spaced that one canopy shades the renewal region of adjacent canopies. The ratio of canopy height (not trellis height) to alley width should not exceed 1 to 1. The renewal region of the canopy, as defined in chapter 6, is that portion in which buds for the following season’s crop develop. The renewal zone is often the current season’s fruit zone. Figure 7.2 illustrates principle 2 for vines trained to divided and nondivided canopies. The shade cast by one canopy on another reduces the photosynthetic function of the shaded leaves and reduces the fruitfulness of developing buds. The 1-to-1 ratio of canopy height to canopy or row width minimizes the shading of any canopy by adjacent ones. Note that principles 1 and 2 attempt to strike a balance between maximizing sunlight interception by grapevine leaves and minimizing intercanopy shade. In theory, principle 2 suggests that with a standard canopy height of 4 to 5 feet (where the height is measured from the bottom to the top of the canopy, not the trellis height), rows (or canopies) may be spaced as closely as 4 or 5 feet apart (Figure 7.2). In practice, equipment width often dictates that row spacing be about 8 to 10 feet. The advent of specialized, narrow vineyard equipment in the United States may permit reduction of row spacing and more efficient use of vineyard area.

Principle 3: Canopy shade should be avoided, especially in the fruit and renewal zone. Leaves and fruit should be exposed to as uniform a microclimate as possible. Canopy shade can significantly reduce fruit and wine quality. The negative effects of shade on fruit composition include elevated levels of potassium, pH, and titratable acidity levels; reduced pigmentation; and reduced concentrations of phenols and soluble solids. Collectively, the altered fruit composition can significantly reduce wine quality. Shade can also retard the development of varietal character and impart vegetative characters to the fruit and wine. Furthermore, shade can promote fruit rot by reducing the resistance of fruit and leaves to infection and by reducing the rate of drying within the canopy. Shade also reduces bud fruitfulness. Buds that developed in shaded renewal zones tend to produce shoots with fewer and smaller clusters and reduced berry set, or those buds may fail to produce shoots at all.

Principle 4: Shoot growth and fruit development should be balanced to avoid either too much or too little leaf area in relation to the weight of fruit. That is, vines should produce just enough foliage to ripen large crops of high quality grapes. Excessively vigorous vines produce large shoots (relatively large in diameter, with long internodes, large leaves, and a tendency to develop active lateral shoots), resulting in dense canopies. Insufficient vigor, on the other hand, typically results in stunted shoots that have insufficient leaf area to ripen the crop. Applying this concept of balance between shoot growth and crop weight requires some method of measuring the relationship between the two. One measure of balance for a given vine is the ratio of crop weight to cane pruning weight. That ratio is sometimes called crop load. (See the following section, “Assessing Canopy Characteristics.”)

Principle 5: Training systems and dormant pruning should promote uniformly positioned fruiting and renewal zones. Uniformly positioned vine parts greatly facilitate mechanization of vineyard operations and even simplify hand labor for certain practices. Shoots that arise from a uniform height on the trellis, for example, are easier to summer prune or hedge. Uniform positioning of fruit makes it easier to remove leaves selectively from the fruit zone, and the fruit can be more rapidly picked by hand than when the fruit is borne over a larger region of the canopy. Creating a uniformly positioned renewal zone is also desirable for physiological reasons relating to uniformity of bud break and shoot growth.

Assessing Canopy Characteristics

One of the most confusing aspects of canopy management for many growers, especially novices, is determining whether the density of their vine canopies is ideal, acceptable, or excessive — in other words, knowing how to decide when corrective measures should be applied. While experienced growers may rely on observation and experience, new growers can benefit — and gain confidence — by assessing canopy characteristics with quantitative methods.

Several inexpensive, rapid techniques are commonly used by vineyardists to assess vine canopies. A collection of eight visual observations has been compiled in the form of a scorecard. (see the book Sunlight into Wine listed in the references.) With a minimum of practice, the scorecard can be used to assess canopies and rate characteristics such as leaf size and canopy density by comparison with an ideal canopy. Canopy scoring is a very useful technique even if not all eight elements of the scoring system are used. Direct measurements are also useful and remove some of the subjectivity inherent in the scorecard approach. Some of the more commonly used measurements are (1) cane pruning weights, (2) crop load, (3) shoot density, (4) canopy transects, and (5) periodic measures of shoot length. Each is described and related to desirable ranges in the following sections.

Cane Pruning Weights

The weight of one-year-old wood (canes) removed from a vine during dormant pruning provides a measure of the vine’s capacity for fruit and shoot growth in the following year. Thus, pruning weights can be used to determine the number of buds to retain at dormant pruning, as described in chapter 6. Pruning weights also indicate whether vines have insufficient or excessive vigor for their available trellis space. Well-balanced vines should have pruning weights ranging from 0.2 to 0.4 pound per foot of canopy. Thus, for vines spaced 8 feet apart in the row and trained to a nondivided canopy system, pruning weights should range from 1.6 to 3.2 pounds. If the majority of vines produce less than 0.2 pound of pruned canes per foot of canopy, consider stimulating vine vigor. These vines probably do not have sufficient vigor to fill their available trellis space with foliage, and crop yields will be unnecessarily constrained. Vine vigor and pruning weights can be increased in several ways, including crop thinning, application of nitrogen fertilizer, and irrigation. Conversely, if most vines produce more than 0.4 pound of prunings per foot of canopy, the vine size and vigor is probably too great and the canopy has been too dense. If other observations and measures support the conclusion that vine vigor and canopy density are excessive, thought should be given to reducing canopy density in the following year. (See the section “Canopy Modification” later in this chapter.)

The practice of summer pruning reduces dormant pruning weights and should be taken into account when evaluating pruning weight data. It is incorrect, for example, to judge a vine with 0.3 pound of prunings per foot of row or canopy to be balanced if that vine required repeated summer pruning during the previous growing season.

Crop Load

Crop load, as defined earlier, is the ratio between the weight of the crop and the weight of pruned canes produced during the same season. This ratio is one measure of whether vines are balanced between vegetative growth and crop production in accordance with principle 4. Determining crop load requires weighing both the fruit at harvest and the canes removed at pruning. For practicality, these measurements are usually limited to 10 or 20 representative vines per vineyard block. Unless damaged or killed, the same vines should be used each year to develop a long-term data base on the vineyard block’s performance. The same vines might be used for the other canopy measures to be described here, and for crop estimation, as described in chapter 12. Research on different varieties under varied growing conditions has shown that crop load ratios should range from 5 to 10. Thus, for vines with cane pruning weights of 2.5 pounds, crops should range from 12.5 to 25 pounds. Vines with crop-load ratios outside the range from 5 to 10 should be evaluated for conditions that might explain the disparity. Crop-load ratios less than 5 indicate excessive vegetation in relation to crop weight (although this condition is normal for young, nonbearing vines). Crop-load ratios greater than 10 are likely associated with overcropping. Symptoms of overcropping include delayed sugar accumulation, reduced fruit coloration, and delayed or reduced wood maturation in the fall. Information gained by measuring crop load in a given year can be used to adjust crops or shoots during the following growing season in order to move toward a more balanced vine.

Shoot Density

Shoot density is a measure of the number of shoots per unit length of canopy and usually relates well to overall canopy density: the greater the shoot density, the thicker, or denser, the canopy. Shoot density can be assessed at any point in the growing season, but it is often done after bud break. The count should be in the range from 4 to 6 shoots per foot of row or canopy. For vines spaced 8 feet apart in the row and trained to a nondivided system, the total number of shoots per vine should range from 32 to 48. The lower number is more suitable for large-clustered, very fruitful varieties such as Seyval and Sangiovese. The higher limit is suitable for small-clustered varieties such as Pinot noir and Riesling. As a starting point, most varieties will produce desirable yields of ripe fruit at a density of five shoots per foot of canopy.

Canopy Transects

Canopy transects are used to quantify canopy thickness (number of leaf layers), porosity (gaps in the foliage), and the percentages of fruit and leaves exposed to sunlight. Also called point quadrats, canopy transects consist of multiple, transectional probes of representative vine canopies with a thin rod. Contacts that the probe tip makes with leaves, fruit, or canopy gaps are recorded as the probe is passed from one side of the canopy to the other. Transects require at least two persons (one handling the probe and one recording data) and are done at or shortly after véraison. In practice, a thin rod is inserted horizontally and at regular intervals (for example, every 6 inches) into the fruit zones of representative vines. A metal tape measure or ruled wooden frame will serve as a guide for probe insertion. Aside from locating the point of probe insertion, the person using the probe should not watch its path through the canopy. An observer tracks the point of the probe and records the nature of all probe contacts as either a leaf (L), a cluster (C), or a gap (G). Gaps are recorded only where the probe fails to contact any leaves or fruit in its passage through the canopy. Contacts with shoot stems are generally ignored. Data are recorded as shown in Table 7.2. In this case, 50 probes were made and the calculations of canopy density were as follows:

Percentage of gaps = gaps ÷ number of probes (6÷50=12%)

Leaf layer number = leaf contacts ÷ number of probes (85 ÷ 50 = 1.7)

Percentage of exterior leaves = exterior leaves ÷ total leaf contacts (68 ÷ 85 = 80%)

Percentage of exterior clusters = exterior clusters ÷ total cluster contacts (15 ÷ 23 = 65%)

Canopy transects, if repeated at least 10 times in each vineyard block, can provide a considerable amount of information on canopy density. Again, these data can be compared to ideal canopy parameters to determine whether remedial action is necessary, either in the current or following year. For example, the percentage of canopy gaps recorded should be about 20 percent, the leaf layer number should range from 1.0 to 2.0, and the percentage of exposed leaves and fruit should be at least 80 percent and 50 percent, respectively. (See Sunlight into Wine.)

Shoot length and lateral shoot development should also be assessed. Ideally, shoots should grow rapidly to 15 or 20 nodes or leaves in length and then stop growing and develop few or no lateral shoots. In reality, shoots of vigorous vines often continue to elongate after fruit harvest and may exceed 50 nodes in length. The same shoots may also develop many persistent summer laterals. Shoot vigor should be assessed periodically throughout the growing season and the shoots hedged, if necessary, to prevent shoot tops from aggravating canopy density and canopy ventilation. (See the section “Summer Pruning” in this chapter.)

| Probe Pass | Nature of Contact* | Probe Pass | Nature of Contact | Probe Pass | Nature of Contact | Probe Pass | Nature of Contact | Probe Pass | Nature of Contact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

LLFL | 11 | G | 21 | LL | 31 | F | 41 | L |

| 2 | LLL | 12 | LL | 22 | LLF | 32 | LL | 42 | G |

| 3 | FLL | 13 | FLLL | 23 | LFLL | 33 | FL | 43 | LF |

| 4 | LL | 14 | LL | 24 | F | 34 | G | 44 | LFL |

| 5 | G | 15 | LFFL | 25 | LL | 35 | LL | 45 | LLL |

| 6 | FL | 16 | LLL | 26 | LLL | 36 | LFL | 46 | LL |

| 7 | LF | 17 | LL | 27 | FLL | 37 | LLL | 47 | F |

| 8 | LL | 18 | LLL | 28 | LL | 38 | G | 48 | LF |

| 9 | F | 19 | FL | 29 | G | 39 | LFLL | 49 | LL |

| 10 | LL | 20 | LLL | 30 | LL | 40 | LLLF | 50 | LFL |

*Nature of probe contact: L = leaf, F = fruit cluster, and G = gap. Contacts with shoot stems are ignored. ↲

Canopy Modification

An assessment of vine canopies using one or more of the methods described may show that the canopies are far from ideal. While drought, infertile soil, and vine disease can all contribute to low vigor and sparse canopies, the opposite condition — high vigor and excessive canopy density — is the more frequent situation, especially with grafted grapevines. Therefore, the canopy modifications described here are intentionally aimed at improving the microclimates of dense canopies. Some of these measures offer only short-term solutions, whereas others, such as canopy division, offer more lasting benefits.

Summer Pruning

Summer pruning, or hedging, involves removing vegetation during the growing season. Typically, this process involves removing shoot tops, retaining only the nodes and leaves needed for adequate fruit and wood maturation. Specific recommendations for hedging depend on the training system used. Hedging is probably most beneficial when applied to low- or mid-wiretrained vines that have upright-positioned shoots. Low-wire bilateral cordon training with upright shoot positioning is such a system. It is fairly easy with this system to top shoots once the shoots have cleared the top of the trellis and before they start to droop over and shade the original canopy. Depending on cordon or cane height on the trellis, shoots that have elongated a foot or so higher than the 6-foot-high trellis will generally have 15 to 20 leaves and can be hedged at a uniform level. Shoot topping does not have as much benefit with vines whose shoots are not positioned — at least not from the standpoint of providing ventilation of the fruit zone. The reason for that reduced response is illustrated by Figure 7.3 and is one of the bases for principle 5, cited earlier. Hedging the low-trained, shoot-positioned vines removes shoot tops that are shading the fruit zone of the original canopy (A). Hedging shoots on high-trained vines, in the absence of downward shoot positioning, does not appreciably improve ventilation in the fruit zone (B). In fact, hedging such vines can sometimes reduce fruit zone ventilation by causing greater lateral shoot growth in the fruit zone. A better canopy management strategy with high-trained vines is the downward “combing” or positioning of shoots during the growing season. Whether the shoot tops are ever removed is not as important as preventing them from growing horizontally. Hedging should be delayed as long as feasible — preferably for 30 or more days after bloom. Retain a minimum of 15 primary (not lateral) leaves per shoot. It is not necessary to count leaves on every shoot, but with most varieties the shoots will average 4½ to 5 feet in length when they bear 15 to 20 primary leaves. Heavy-duty, scissor-type hedge shears are the most commonly used hedging tools. Gasoline or battery-operated cutter-bar hedgers have also been used. In either case, the process is less tiring if one works with arms at chest height by standing on an elevated platform such as a trailer.

Altered Training Systems

Training systems that promote ventilation of fruit zones have an advantage over those that tend to hide the fruit within shaded canopy interiors. The training system should promote maintenance of a thin canopy of foliage (no more than two leaf layers thick). For large, vigorous vines in established vineyards, conversion to divided canopy training might be the most practical way to achieve the desired canopy density. Canopy division should be considered when the majority of vines have average pruning weights in excess of 0.3 to 0.4 pound of prunings per foot of canopy in the absence of summer pruning. Several approaches to canopy division should be considered and specific guidelines sought before pursuing this course. The establishment of multiple trunks before the year of conversion makes the process much easier and avoids loss of crop in the conversion year.

Canopy division is not always practical for existing plantings. For nondivided canopies, bilateral cordon training coupled with upright shoot positioning (to be discussed later) is one of the more efficient systems in use in North Carolina, both in terms of pruning labor and canopy management. With low- to mid-wire cordon training (36 to 44 inches above ground), the shoots originate at a uniform height and fruit is borne in a fairly limited region of the canopy. Both of those features greatly facilitate canopy management practices such as shoot thinning, selective leaf pulling, and shoot positioning. Cordon training (either high or low) is less desirable, however, in situations where winter cold injury makes the perennial maintenance of cordons difficult or impossible.

Shoot Positioning and Shoot Thinning

Some shoot positioning should be an integral part of vineyard management. The objective of shoot positioning is to position the vine’s shoots and foliage uniformly in the vine’s available trellis space and minimize mutual leaf shading. For high-trained vines, shoot positioning entails combing the shoots down to form a curtain of well-exposed foliage. For low-trained vines (for example, those trained to a low, bilateral cordon system), the shoots should be positioned upright, again to form a thin, well-exposed canopy. Paired catch wires can be added to the trellis to sandwich the shoots and prevent them from being blown free once positioned. Also, various shoot tying or taping devices are commercially available. Shoot positioning is easier if done repeatedly rather than waiting until the shoots are very long and in need of substantial redirection. If the process is started at about bloom time, most shoots can be positioned without breakage and before their tendrils have secured the shoots to wires or other supports. Depending upon the number of foliage catch wires used on the trellis, some repositioning of shoots may be necessary between bloom and véraison to maintain the desired canopy dimensions.

Shoot thinning is also a good technique for maintaining a more open canopy. An added advantage of shoot thinning is that it can control crop in varieties that tend to overproduce (for example, Seyval). Shoot thinning is done soon after bud break and preferably before shoots are more than 18 to 24 inches long. Longer shoots are more difficult to remove. A convenient rule of thumb is to retain four to six shoots per foot of canopy (as recommended previously under “Shoot Density”). The choice of shoots to be retained should be made with regard to their spacing on the cordon or trellis and their fruitfulness. Except where needed for spurs the following year, unfruitful shoots should be removed in preference to fruitful shoots unless crop reduction is desired.

Selective Leaf Removal

The selective removal of leaves from the area around fruit clusters has been practiced increasingly in the United States in recent years. This practice can be an effective tool for fruit rot control. The leaves can be removed anytime between fruit set and véraison; however, early leaf removal may have to be repeated to keep fruit clusters open, and post-vérasion leaf pulling can result in the fruit being sunburned. The goal of leaf pulling is to increase ventilation and light penetration into the fruit zone. Generally, only one to three leaves per shoot are removed. It is not necessary to remove all leaves in the fruit zone. The objective is to have an average of one to two leaf layers remaining in the fruit zone after the leaves have been pulled. Leaf pulling is more efficient with training systems that have uniformly placed fruit zones (such as with bilateral cordon training), compared with systems in which one must hunt for the fruit clusters. With the latter systems, as with hedging, more basic canopy management techniques such as training system conversion and shoot positioning may be more useful than leaf pulling. Leaf pulling is most often done by hand, but some vineyards use tractor-mounted machines to increase the speed of operation.

References

Smart, R. E., J. K. Dick, I. M. Gravett, and B. M. Fisher. 1990. Canopy management to improve grape yield and wine quality: Principles and practices. South African Journal of Enological Viticulture 11:3-17.

Smart, R. E., and M. Robinson. 1991. Sunlight into Wine: A Handbook for Wine Grape Canopy Management. Winetitles, Adelaide, Australia.

Publication date: Feb. 28, 2007

Reviewed/Revised: Aug. 11, 2025

Other Publications in The North Carolina Winegrape Grower’s Guide

- Chapter 1. Introduction

- Chapter 2. Cost and Investment Analysis of Chardonnay (Vitis Vinifera) Winegrapes in North Carolina

- Chapter 3. Choice of Varieties

- Chapter 4. Vineyard Site Selection

- Chapter 5. Vineyard Establishment

- Chapter 6. Pruning and Training

- Chapter 7. Canopy Management

- Chapter 8. Pest Management

- Chapter 9. Vine Nutrition

- Chapter 10. Grapevine Water Relations and Vineyard Irrigation

- Chapter 11. Spring Frost Control

- Chapter 12. Crop Prediction

- Chapter 13. Appendix Contact Information

- Chapter 14. Glossary

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.