Grapevines require 16 essential nutrients for normal growth and development (Table 9.1). Carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen are obtained as the roots take in water and as the leaves absorb gases. The remaining nutrients are obtained primarily from the soil. Macronutrients are those used in relatively large quantities by vines; natural macronutrients are often supplemented with applied fertilizers.The micronutrients, although no less essential, are needed in very small quantities. When one or more of these elements is deficient, vines may exhibit foliar deficiency symptoms, reduced growth or crop yield, and greater susceptiblity to winter injury or death. The availability of essential nutrients is therefore critical for optimum vine performance and profitable grape production.

Ensuring adequate vine nutrition begins in the preplant phase of vineyard establishment. Soil samples should be collected at that time to determine whether lime or other fertilizers are needed. Soil depth, texture, and internal drainage must also be evaluated before the vineyard is established because deficiencies in those factors can lead to poor root growth and reduced nutrient absorption.

Grapevines typically grow very slowly during the first few months after planting. That slow growth is due to a small root system and minimal carbohydrate reserves in the rooted cutting or grafted vine. Trying to stimulate growth with fertilizer application is tempting. Unfortunately, young vines are occasionally injured more than benefited by fertilizer applied during the first season. Under most conditions, if the vineyard soil was well prepared and the soil pH was adjusted before planting, vines will require very little if any fertilizer in the first few years of growth.

Poor growth of young vines is more often due to lack of water, competition by weeds, overcropping, or poor disease control than to inadequate soil fertility. Fertilizer will not compensate for those stresses. Besides possible root burning, excessive nutrient availability can lead to poor wood maturation in the fall and subsequent cold injury during the winter. Applying soil fertilizer in the year of planting is therefore recommended only if the soil is inherently infertile. In that case, a 4-ounce-per-vine application of a 10-10-10 fertilizer (or one having an equivalent nitrogen analysis) is generally sufficient. The fertilizer should be applied in a ring 12 to 18 inches from the base of the vine after planting or just before bud break for vines set the previous fall.

| Obtained from Air and Water | Obtained from Soil | |

|---|---|---|

| Macronutrients | Micronutrients | |

|

Carbon (C) Hydrogen (H) Oxygen (O) |

Nitrogen (N) Phosphorus (P) Potassium (K) Calcium (Ca) Magnesium (Mg) Sulfur (S) |

Iron (Fe) Manganese (Mn) Copper (Cu) Zinc (Zn) Boron (B) Molybdenum (Mo) Chlorine (Cl) |

As an alternative to soil application, a foliar fertilizer can be used on young vines. The foliar fertilizer provides a rapid but temporary response. Sprayable 20-20-20 fertilizer or materials of a similar analysis are suitable, but read the fertilizer directions for rates of application and precautions.

Assessing Nutrient Needs of Mature Vines

As vines mature and crops are harvested, many vineyards require periodic application of one or more nutrients and adjustment of pH with lime. Vineyards are sometimes fertilized on the basis of speculation, habit, or wishful thinking. At the other extreme, some growers avoid any fertilizer for fear of overstimulating growth. In other cases, entire vineyard blocks might be fertilized when only specific areas of the block require fertilizer. Inappropriate vineyard fertilization can result in inadequate or excessive vine vigor, poor fruit set, impaired leaf photosynthetic ability, and reduced fruit quality. In some cases, such as with boron, excess availability can cause vine injury more severe than the deficiency symptoms. Therefore, it is important that growers have a sound basis for determining the fertilizer needs of their vines.

No single method exists for accurately assessing vine nutrient needs. Instead, a combination of soil analysis, plant tissue analysis, and visual symptoms should be used. These methods are discussed in detail in the following sections of this chapter.

Soil Analysis

Physical soil features should be evaluated in the site selection process. (See chapter 4.) The soil must meet minimum standards of depth and internal water drainage. Soil survey maps should be consulted to determine the agricultural suitability of any proposed site. The history of crop production at the site or in nearby vineyards can provide some indication of grape production potential. Sites that have been in recent cultivation are usually in better condition than pasture or abandoned farmland.

Detailed soil analyses must be made before the vineyard is established, primarily to determine pH but also soil fertility. Soil test kits are available from either county Cooperative Extension centers or regional agronomists with the NCDA&CS. (See the listing of soil and plant tissue testing services at the end of this chapter.) Soil samples can be collected either with a shovel or a cylindrical soil probe. In either case, samples must be representative of the area to be planted. Sites larger than 2 or 3 acres should be subdivided and each section sampled separately if there are differences in topography or soil classification. Collect samples when the soil is moist and not frozen; fall is an excellent time. Each sample should consist of 10 to 20 subsamples that are thoroughly mixed. Exclude surface litter, sod, large pebbles, and stones, and retain about a pound of the mixed soil for testing. The top few inches of soil are usually quite different from deeper soil with respect to pH and nutrient availability. For this reason, it is best to divide each soil probe into two samples: one from the 0to 8-inch depth and a second from the 8- to 16inch depth. Grape roots can grow much deeper than 16 inches in loose, well-aerated soil. Because the ability to alter soil characteristics significantly below that depth is very limited, there is little point in collecting deeper samples.

Soil test results will indicate whether adjustments to pH and macronutrients are necessary. Soil test data are not customarily used to assess the need for nitrogen or trace elements for vineyards, although tests for those nutrients can be included if there are reasons to suspect a deficiency. The test results are accompanied by specific recommendations for correcting soil deficiencies.

Perhaps the most important information provided by the soil test is the pH value. Soil pH is a measure of acidity or alkalinity on a scale from 0 to 14. A value of 7 is neutral. Values less than 7 reflect acidity, whereas numbers above 7 indicate alkaline conditions. The pH scale is logarithmic; a pH of 5.0 is 10 times more acidic than a pH of 6.0 and 100 times more acidic than a pH of 7.0. Soil pH is determined by many factors, including the parent material, the amount of organic matter, the degree of soil leaching by precipitation, and previous additions of lime or acidifying fertilizers.

Grape species differ substantially in the optimum pH for growth. Varieties of Vitis vinifera generally grow best at a pH between 6.0 and 7.0, whereas the native American grapes (such as Concord and Niagara) and the hybrids tolerate lower pH values (5.5 to 6.0).

Adjusting Soil pH

Soil pH adjustments in eastern U.S. vineyards, with few exceptions, are made to increase rather than decrease pH. The pH of acid soils can be raised by applying lime. That simple statement unfortunately oversimplifies the complexity of soil acidity problems, particularly in established vineyards. It is very difficult to increase the pH below the top few inches of soil once vines have been planted. This is particularly true once a permanent cover crop has been planted and cultivation is no longer desirable. For that reason it is extremely important to determine soil pH and raise it if necessary before the vineyard is established.

The applied lime should be incorporated as thoroughly and as deeply as possible. Common agricultural-grade liming materials (for example, ground limestone) have very low solubilities and will move very little, if at all, below the first few inches when applied to the soil surface. Even with cultivation, lime incorporation beyond about 12 inches is unlikely with conventional tillage equipment. Subsoil pH can be raised somewhat by applying lime and cultivating deeply (12 to 18 inches) with a chisel plow or subsoiler.

Most vineyard soils tend to become acidic even if they are limed to a pH of 6.5 at the time of establishment. Acidification occurs through leaching of basic ions from the soil profile, through microbial activity, and by the addition of acidifying fertilizers such as ammonium sulfate. Fungicidal sulfur applications can also be expected to reduce soil pH. Soil pH should therefore be monitored every two to three years after vineyard establishment.

The materials commonly used for agricultural liming are the oxides, hydroxides, carbonates, and silicates of calcium or mixtures of calcium and magnesium. Commercial bulk application of lime typically involves spreading ground limestone, which contains calcium carbonate or mixtures of calcium and magnesium carbonate. Limestone containing a high proportion of magnesium carbonate is termed dolomitic limestone. Calcitic limestone is more reactive than dolomitic limestone; however, dolomitic limestone can be useful in situations where available magnesium is low. The oxides and hydroxides (hydrated lime is calcium hydroxide) are more reactive and have a greater neutralizing value than the carbonates. These materials are, however, unpleasant to handle. They absorb moisture and can cake, and they can irritate skin and injure tissues of the eyes, nose, and mouth. Oxides and hydroxides are also more expensive than carbonates. In addition to dry materials, liquid lime formulations are available from some distributors.

The choice of liming material is often determined by what is locally available. Most of the cost of liming is due to transportation and spreading. The amount of lime needed for a particular acidity problem is affected by a number of factors including soil pH, texture, and organic matter content; the grape species to be planted; and the type and particle size of lime used. Obviously, recommendations cannot be provided here for all situations. Table 9.2, however, provides some guidelines for liming based on initial pH and soil type. In practice, individual rates of lime application should not exceed 4 tons per acre. Where soils are strongly acidic, several applications of 2 to 3 tons per acre each over a period of several years will likely be more effective than a single, massive dose.

Plant Tissue Analysis

Analyzing plant tissue provides an objective means of determining the nutrient status of grapevines.

| pH of Unlimed Soil | Soil Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sandy | Loamy | Clayey | |

| pH desired: 6.8 | |||

| 4.8 | 4.25 | 5.75 | 7.0 |

| 5.0 | 4.0 | 5.25 | 6.25 |

| 5.5 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.75 |

| 6.0 | 2.0 | 2.75 | 3.25 |

| 6.5 | 1.25 | 1.5 | 2.0 |

| pH of Unlimed Soil | Soil Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sandy | Loamy | Clayey | |

| pH desired: 6.5 | |||

| 4.0 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 5.0 |

| 5.0 | 3.0 | 3.75 | 4.25 |

| 5.5 | 1.75 | 2.5 | 3.0 |

| 6.0 | 1.25 | 1.5 | 2.0 |

Tissue analysis reveals the concentration of essential nutrients or elements absorbed by or within vine tissues. In most respects, tissue analysis is superior to soil analysis, which indicates only the relative availability of nutrients. A high availability of a particular nutrient in the soil does not necessarily mean that the plant can extract enough of that nutrient to meet its needs.

To be meaningful, tissue analysis must entail:

- a standardized tissue sampling procedure

- accurate and precise analytical methods for determining the elemental concentrations of tissue samples

- standard references with which to compare diagnostic sample values; and

- a means of interpreting diagnostic data and making sound fertilizer recommendations to the grower.

In practice, a grower collects the tissue sample and submits it to a laboratory for analysis. The laboratory technician follows standardized procedures for determining the mineral nutrient concentration of the tissue. Elemental concentra-tions of the diagnostic sample are compared with standard grapevine tissue references from healthy vines. Based on those standards, elements or nutrients in the diagnostic sample are classified as being adequate, high, or low (deficient). Fertilizer recommendations to increase the concentration of nutrients that are low or deficient can be made either by laboratory personnel or a grape special-ist. The NCDA&CS Agronomic Division can provide further information on submission procedures.

Specific recommendations for tissue sample collection depend on the grower’s objectives. There are basically two reasons to conduct plant tissue analyses. One is for the routine evaluation of nutrient status. The other is to diagnose a particular visible disorder for which a nutrient deficiency is the suspected cause.

Routine Nutrient Status Evaluation

The general nutrient status of vines should be evaluated annually or every other year to gauge the vineyard’s need for or response to applied fertilizer. These tests will usually detect deficiencies before symptoms become visible. Corrective fertilizer applications are then usually unnecessary because minor deficiencies can be corrected by adjusting the fertilizer used in routine maintenance applications.

The concentration of most essential nutrients varies in the plant throughout the growing season. For example, the concentration of nitrogen in grape leaves is higher at bloom than at véraison (onset of rapid fruit maturation) or near harvest. For other nutrients, such as potassium, research has shown that foliar concentrations in late summer (70 to 100 days after bloom) are better correlated with vine performance than are concentrations diagnosed at bloom. Sample vines at different times of the season to evaluate different nutrients. The NCDA&CS Plant Analysis Laboratory has very reasonable charges for plant analysis. If you take only one plant tissue sample each season, collect that sample at full bloom, which is when about two-thirds of the flower caps have been shed. Because the tissue concentrations of many of the essential elements change rapidly in the early part of the growing season, it is important to sample as close to full bloom as possible.

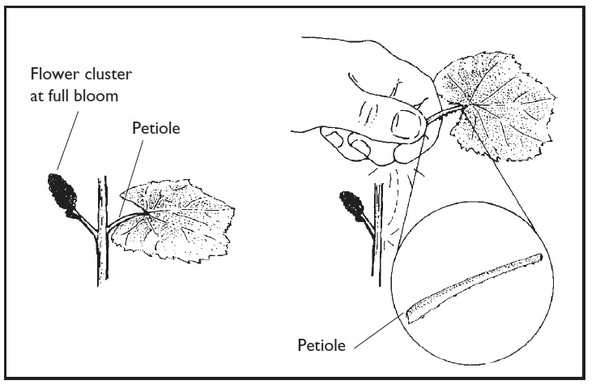

Sample each variety separately because nutrient concentrations may vary somewhat among varieties. Collect a total of 100 petioles from leaves located opposite the first or second flower cluster from the bottom of the shoot. Petioles are the slender stems that attach the leaf blade to the shoot (Figure 9.1). Collect petioles systematically throughout the vineyard block to ensure that the entire block is represented. If different portions of the vineyard (for example, hills versus low-lying areas) exhibit differences in vine growth, collect separate samples from each of those areas. Collect no more than one or two petioles per vine. Choose leaves from shoots that are well exposed to sunlight and that are free of physical injury or disease. Immediately separate the petioles from leaf blades and place the petioles in a small, labeled paper bag or envelope.

Sufficiency ranges for nutrients from bloom-sampled vines are presented in Table 9.3. Concentrations that exceed the sufficiency range do not necessarily indicate a problem. For example, recent applications of fungicides that contain manganese, copper, or iron can elevate the test results for those elements.

Certain elements, notably potassium, are best evaluated in late summer when their concentrations become more stable. Where bloom-time samples indicate questionable nutrient levels, particularly of potassium, collect a second set of samples 70 to 100 days after bloom. These late-summer samples should consist of 100 petioles collected from the youngest fully expanded leaves of well-exposed shoots. The youngest fully expanded leaves will usually be located from five to seven leaves back from the shoot tip. Separate the petioles from leaf blades and submit only the petioles as described above.

Diagnosing Visible Vine Disorders

For troubleshooting suspected nutrient deficiencies, sample anytime during the season that symptoms become apparent. Collect 100 petioles from symptomatic leaves regardless of their shoot position. In addition, collect an equal number of petioles from nonsymptomatic or healthy leaves in the same relative shoot position from which affected leaves were collected. Label and submit the two independent samples so that their elemental concentrations can be compared.

Visual Observations

Inspections of foliage for symptoms of nutrient deficiencies and observations of vine vigor and crop size provide important clues as to whether vines are suffering nutrient stress. However, it is possible to be misled by foliar disorders because some are not nutritional in origin. For example, some herbicide toxicity symptoms are similar to those of certain nutrient deficiencies. And, to the inexperienced person, European red mite feeding injury may be misinterpreted as a nutrient deficiency. The correct interpretation of foliar disorders requires a certain amount of experience and understanding of pattern expression. In general, there are three different patterns of symptoms to examine: patterns within the vineyard; patterns on a given vine; and patterns on a particular leaf.

Variation in symptoms within the vineyard can provide useful clues as to whether a nutrient deficiency is the cause of observed symptoms. With undulating or hilly topography, nutrient deficiency symptoms are usually first observed on the higher sites, especially where soil erosion has occurred. In particular, nitrogen, potassium, magnesium, and boron deficiencies may be expected to occur first at higher sites because of thinner topsoil and reduced moisture. Soil moisture aids movement of nutrients to the root-soil interface, and under drought conditions, nutrient deficiencies can develop.

Vine-to-vine variation in symptoms also provides meaningful clues. Generally, a nutrient deficiency will affect sizable portions of a vineyard and rarely only one or two vines at random. Peculiar symptoms that appear on only a few vines throughout the vineyard, or where healthy vines alternate with symptomatic vines, suggest a biological pest. Leafroll virus, for example, will produce distinct foliar symptoms on some red- fruited varieties (for example, Cabernet franc), and affected vines may be directly adjacent to healthy vines.

The position or age of symptomatic leaves on a given vine also provides information about which nutrient might be causing the deficiency symptoms. Generally, deficiencies of the mobile elements such as nitrogen, potassium, and magnesium appear on older or midshoot leaves. Deficiency symptoms of some of the less mobile trace elements, notably iron and zinc, first appear on the youngest leaves of the shoot.

Finally, the particular pattern of symptoms on individual leaves can also yield information. Specific patterns for individual elements are described in the following section and are summarized in Table 9.4 for three commonly deficient macronutrients.

In addition to foliar symptoms, observations of vine vigor and fruit set and yield can be used to further diagnose a suspected nutrient deficiency. Uniformly weak vine growth, for example, may point to a need for added nitrogen. However, first consider that water stress, overcropping, and disease can also constrain growth. Poor fruit set, straggly clusters, and uneven berry size and shape could suggest a boron deficiency. Remember that similar symptoms might point to a tomato ringspot virus infection.

It should be obvious, then, that the diagnosis of nutrient deficiencies depends on experience and should be confirmed with a combination of visual examination and laboratory tests.

| Nutrient | Leaf Injury Pattern | Location of the Most Severely Affected Leaves | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild Symptoms | Severe Symptoms | ||

| Nitrogen | General fading of green leaf color | Pronounced leaf yellowing or chlorosis | Basal to midshoot leaves |

| Potassium | Interveinal and marginal chlorosis | Necrosis or scorching of leaves from margins inward | Midshoot leaves |

| Magnesium | Interveinal chlorosis that does not extend to leaf margin on at least some leaves | Necrotic spots and leaf chlorosis, including chlorosis of leaf margins | Basal to midshoot leaves |

Specific Nutrient Deficiencies and Their Correction

Fortunately, of the 16 essential elements required by grapevines, only nitrogen, potassium, magne-sium, and boron are commonly deficient in North Carolina. This section provides an overview of the role of these nurtients, the symptoms of deficien-cies, and options for correcting the deficiencies.

Nitrogen

Role of Nitrogen

Vines use nitrogen to build many compounds essential for growth and development. Among these are amino acids, nucleic acids, proteins (including all enzymes), and pigments, including the green chlorophyll of leaves and the darkly colored anthocyanins of fruit.

Symptoms and Effects of NitroGen Deficiency

Nitrogen deficiency is not as easily recognized as are deficiencies of certain other elements such as magnesium or potassium. The classic symptom is a uniform light green color of leaves (Figure 9.2), as compared to the dark green of vines that receive adequate nitrogen. Nitrogen deficiency is considered severe if leaves show this uniform light green color. Other clues pointing to nitrogen deficiency are slow shoot growth, short internodal length, and small leaves. Insufficient nitrogen can also reduce crop yield through a reduction in clusters, berries, or berry set. Thus, nitrogen deficiency might be observed as a reduction in yield over several years. It is important to remember, however, that other factors such as drought, insect and mite pests, and overcropping can also cause similar symptoms.

Excessive Nitrogen

Nitrogen stimulates vegetative growth. If excess nitrogen is available to vines, excessive vine growth may occur. Shoots of such vines can grow late into the fall and may attain a length of 8 to 10 feet. Conventional trellis and training systems do not accommodate such extensive growth, and some form of summer pruning might be needed to create an acceptable canopy microclimate for fruit and wood maturation. The percentage of shoot nodes that mature (become woody) can also be decreased when excessive nitrogen causes growth to continue late in the season.

Yields can also suffer from excessive nitrogen uptake. Yield reductions can result from reduced bud fruitfulness caused by shading of buds in the previous year. Yields can also be reduced by inadequate fruit set in the current year. In the latter situation, vigorous shoot tips can provide a stronger “sink” than the flower clusters for carbohydrates, nitrogenous compounds, and hormones necessary for good fruit set.

Some growers believe that any added nitrogen will reduce the cold hardiness of vines. This is an unfortunate misconception. If vines exhibit poor vigor and are not producing good crops as a result of nitrogen deficiency, the addition of moderate amounts of nitrogen (30 to 60 pounds of actual nitrogen per acre) will not reduce their cold hardiness and will undoubtedly improve their overall performance.

Causes of Nitrogen Deficiency

Nitrogen is the essential element used in greatest amounts by vines. In older vineyards, nitrogen is the nutrient that most commonly must be added routinely. Once absorbed by the vine, nitrogen can be lost through fruit harvest and the annual pruning of vegetation. Considering that grape berries contain approximately 0.18 percent nitrogen, a 5-ton crop removes approximately 18 pounds of nitrogen per acre from the vineyard. The reduction in nitrogen is even greater if cane prunings (about 0.25 percent nitrogen) are removed from the vineyard.

Given a removal of nitrogen in the crop and prunings with no input (fertilizer), most soils will eventually be depleted of readily available nitrogen. Nitrogen depletion occurs most rapidly in soils having a low organic matter content. Much of the nitrogen in soils is associated with organic matter. Through a series of reactions involving soil organisms, the pool of organic nitrogen is converted to other forms (ammonia and nitrate-nitrogen) capable of being absorbed by vines and other plants. When soil nitrogen reserves are exhausted, nitrogen must be applied to satisfy the vines’ needs.

Vines grafted to pest-resistant rootstocks (for example, Vitis vinifera varieties) are often more vigorous than nongrafted vines, and their requirements for nitrogen fertilizer may be substantially less than that for own-rooted vines. However, grafted grapevines are not immune to nitrogen deficiency. The robust root system of grafted vines is capable of exploring a large volume of soil. Even so, continued cropping or soil mismanagement will eventually exhaust available soil nitrogen.

Assessing the Need for Nitrogen Fertilizer

No single index serves well as a guide in assessing the vine’s need for nitrogen fertilizer. Instead, a number of observations should be made over several consecutive years to determine the vine’s nitrogen status. Vines can be grouped into three general categories with respect to their nitrogen status: deficient, adequate, and excessive.

Nitrogen deficient vines commonly exhibit these symptoms:

- Vines consistently fail to fill the available trellis with foliage by the first of August.

- Crop yield is chronically low.

- Cane pruning weights are consistently less than ¼ pound per foot of row or per foot of canopy for divided-canopy training systems (for example, less than 1.75 pounds for vines spaced 7 feet apart in the row).

- Mature leaves are uniformly small and light green or yellow.

- Shoots grow slowly and have short internodes.

- Shoot elongation ceases in midsummer.

- Fruit quality may be poor, including poor pigmentation of red-fruited varieties.

- Bloom-time petiole nitrogen concentration is less than 1 percent.

If the nitrogen status is adequate, vines typically exhibit these characteristics:

- Vines fill the trellis with foliage by the first of August.

- Yields are acceptable.

- Cane pruning weights average 0.3 to 0.4 pound per foot of row.

- Mature leaves are of a size characteristic for the variety and are uniformly green.

- Shoots grow rapidly and have internodes 4 to 6 inches long.

- Shoot growth ceases in early fall.

- Fruit quality and the maturation period are normal for the variety.

- Bloom-time petiole nitrogen concentration is between 1.2 and 2.2 percent.

With excessive nitrogen, vines may present these symptoms:

- Shoots fill trellis with an excess of foliage: shoots are 8 to 10 feet long by mid-July.

- Fruit yields are low because there are few clusters, poor fruit set, or both.

- Cane pruning weights consistently exceed 0.4 pound per foot of row (for example, 3 or more pounds of cane prunings for vines spaced 7 feet apart in the row).

- Mature leaves are exceptionally large and very deep green.

- Shoot growth is rapid; internodes are long (6 inches or more) and possibly flattened.

- Shoot growth does not cease until very late in the fall.

- Fruit maturation is delayed.

- Bloom-time petiole nitrogen is greater than 2.5 percent.

Again, the occurrence of symptoms listed as typical of nitrogen-deficient vines does not prove that nitrogen is limiting growth. Drought, in particular, can cause similar symptoms. Nitrogen fertilizer will not overcome problems arising from the lack of water or other growth-limiting factors.

Correcting Nitrogen Deficiency

It is far better to prevent nitrogen deficiency than to wait until correction of a deficiency is necessary. Maintaining an appropriate nitrogen status is based on experience, observations of vine performance, and supplemental use of bloom-time petiole analysis of nitrogen concentration. Once nitrogen deficiency symptoms are visually detected, yield or quality losses have already been sustained, and the deficiency will require time to correct.

If application of nitrogen fertilizer is warranted, a prudent starting point is to apply it at a rate of 30 to 50 pounds of actual nitrogen per acre. Do not be surprised if an initial application of nitrogen has no pronounced effect in the year of application. It sometimes takes two years for added nitrogen to have an impact on vine performance because much of a vine’s early-season nitrogen needs are met by nitrogen stored in the vine from the previous growing season. Thus, nitrogen applied to vines in the current year may have its greatest benefit in the following season.

Several forms of nitrogen fertilizer are commercially available. All will satisfy the vines’ needs (Table 9.5). Urea or ammonium nitrate are commonly the most economical forms in this region. Ammonium-based fertilizers such as urea and ammonium nitrate should be incorporated into the soil to minimize volatilization (and hence loss) of ammonia. Rain within one or two days of application is a convenient but unpredictable means of incorporation. As an alternative, soil cultivation, as by dehilling of grafted vines, is acceptable. Recommendations for application of actual nitrogen must be translated into rates based on commercial formulations. A recommended application rate of 40 pounds of actual nitrogen per acre, for example, would require 87 pounds of urea, 114 pounds of ammonium nitrate, or 190 pounds of ammonium sulfate per acre. Nitrogen fertilizer should be applied only during periods of active uptake to minimize loss through soil leaching. These times include the period from bud break to véraison and immediately after fruit harvest. Generally, routine maintenance applications should be made at or immediately after bud break. This timing coincides with normal precipitation patterns that increase the likelihood of soil incorporation. Where applications of more than 75 pounds of actual nitrogen per acre are required, a split application should be used, applying 50 to 75 percent of the total nitrogen at bud break and the balance immediately after bloom. This method ensures that some nitrogen is absorbed with spring rains, but it also extends the absorption into the most efficient phase of nutrient uptake. The disadvantage of this approach is the extra labor involved.

Apply nitrogen in a band under the trellis rather than broadcasting it over the entire vineyard floor. Under-trellis application can be done either by placing the fertilizer in a ring around individual vines or by banding it with a modified tractor-mounted fertilizer spreader. The quantities of nitrogen used are so small that ringing individual vines — at 12 to 18 inches from the trunks — is a practical alternative for small vineyards. Regardless of the method used, apply nitrogen only where it is needed.

| Nitrogen Source | Percentage of Actual Nitrogen | Price Per 50-pound Baga | Cost Per Pound of Actual Nitrogen |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urea | 46 | $11.25 | $0.49 |

| Ammonium nitrate | 35 | $9.00 | $0.51 |

| Ammonium sulfate | 21 | $6.75 | $0.64 |

| Di-ammonium phosphate | 18 | $9.40 | $1.04 |

| Calcium nitrate | 16 | $9.50 | $1.19 |

Note: To this list could be added liquid nitrogen, anhydrous ammonia, and “complete” fertilizers such as 10-10-10. However, specialized equipment for application or greater cost per unit of nitrogen may need to be considered with those forms.

a Prices quoted are those for piedmont North Carolina in 2005. Prices are significantly lower if the product is purchased in bulk. However, the quantities of nitrogen needed in most North Carolina vineyards do not warrant the inconvenience of bulk handling. ↲

Potassium

Role of Potassium

Potassium functions in a number of regulatory roles in plant biochemical processes, including carbohydrate production, protein synthesis, solute transport, and maintenance of plant water status. Although potassium can account for up to 5 percent of tissue dry weight, it is not normally a component of structural compounds.

Symptoms and Effects of Potassium Deficiency

Foliar symptoms of potassium deficiency become apparent in mid-to late summer as a chlorosis or fading of the leaf’s green color. This yellowing commences at the leaf margin and advances toward the center of the leaf. Leaf tissue adjacent to the main veins remains darker green, at least when the potassium deficiency is mild (Figure 9.3). Midshoot leaves are the first to express these symptoms.

With advanced or more severe potassium deficiency, affected leaves will have a scorched appearance where the chlorotic zones progress to brown necrotic tissue. Leaf margins will curl either upward or downward. Severe potassium deficiency also reduces shoot growth, vine vigor, berry set, and crop yield. Fruit quality suffers from reduced accumulation of soluble solids and poor coloration.

The symptoms described can also appear under conditions of extreme drought or extreme moisture. Furthermore, leaf scorching can also occur under some conditions from pesticide phytotoxicity. Phytotoxicity is generally most acute on the younger leaves, and shoots soon develop newer, unaffected leaves.

Causes of Potassium Deficiency

Vines grown in soils that are very high in ex- changeable calcium and magnesium and low in exchangeable potassium may require periodic potassium application. Potassium absorption may also be limited when the soil pH is very basic (greater than 7.0) or acidic (less than 4.0). Experi- ence and tissue analysis results from Virginia vineyards have rarely shown a need for added potassium. Indeed, excessive absorption, as evidenced by very high tissue potassium levels (3 to 5 percent of dry weight), is more often the case. There is some evidence that high foliar concentrations of potassium are associated with elevated potassium levels in maturing fruit, and under some conditions the fruit may have an undesirably high pH, which can negatively affect wine quality. Thus, aside from the cost, there is good reason not to apply potassium unless it is needed.

Assessing the Need for Potassium Fertilizer

Visual observation of vine performance and foliar symptoms should be coupled with routine leaf petiole sampling to determine the potassium status of vines. Research in New York indicated that late-summer tissue sampling (70 to 100 days after bloom) was superior to bloom-time sampling for accurately gauging the vines’ potassium status. Thus if visual observations (Table 9.4) or the bloom-time tissue analysis used for other nutrients indicate a marginal potassium level (Table 9.3), additional tissue samples should be tested in late summer to confirm the need for added potassium. Petioles of recently matured leaves (about the fifth to seventh back from the shoot tip of non-hedged shoots) are collected for late-summer samples. As in sampling for other nutrients, separate samples should be collected from regions of different topography or soil type.

Correcting Potassium Deficiency

Potassium deficiency is corrected by applying potash fertilizer. Short-term correction can be made with foliar-applied potassium fertilizer; however, the less costly and longer-lasting remedy is soil application. Two commonly used potash fertilizers are potassium sulfate and potassium chloride (also called muriate of potash). Potassium chloride is generally much less expensive. Potassium may also be applied as potassium nitrate, but this fertilizer is usually very expensive. Application rates vary with the severity of potassium deficiency (see Table 9.6). Potassium fertilizers should be banded under the trellis rather than broadcast over the vineyard floor. Banding assures that a major portion of the fertilizer will be available for root uptake and will minimize the amount fixed by soil colloids. Potassium can be applied anytime, but maximal uptake will probably occur between bud break and véraison and again immediately after fruit harvest.

| Vine Deficiency | Per Vine (lb) | Per-Acre Equivalent (lb)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KCl | K2SO4 | KCl | K2SO4 | |

| Severe | 1.5 | 2.0 | 900 | 1,200 |

| Moderate | 1.0 | 1.3 | 600 | 800 |

| Mild | 0.5 | 0.7 | 300 | 400 |

a Based on approximately 600 vines per acre. ↲

Magnesium

Role of Magnesium in the Plant

Magnesium has several functions in the plant. It is the central component of the chlorophyll mol- ecule — the green pigment responsible for photosynthesis in green plants. Magnesium also serves as an enzyme activator of a number of carbohydrate metabolism reactions. In addition, the element has both structural and regulatory roles in protein synthesis.

Symptoms and Effects of Magnesium Deficiency

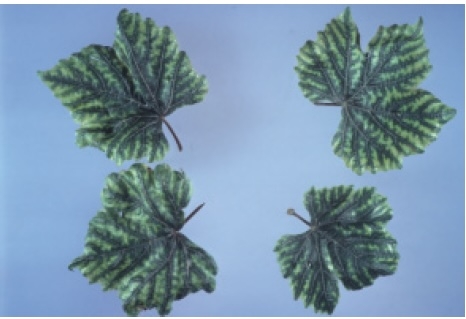

Deficiency is usually expressed in mid- to late summer when basal (older) leaves develop interveinal (between the veins) chlorosis or yellowing. The nature of the chlorosis depends upon the grape variety, but generally the central portion of the leaf blade loses green color to a greater extent than the leaf margins (Figure 9.4). Tissue near the primary leaf veins remains a darker green. As symptoms progress, the yellow chlorosis can become necrotic and brown. Magnesium deficiency of red-fruited varieties can cause leaves to turn reddish rather than chlorotic. Because magnesium is mobile within the vine, younger leaves are supplied with magnesium at the expense of older leaves. Magnesium symptoms are therefore usually confined to the older leaves except in cases of severe deficiency.

Causes of Magnesium Deficiency

Grapevines express magnesium deficiency symp- toms because they are not obtaining sufficient magnesium from the soil. Magnesium accounts for approximately 0.25 to 0.75 percent of the dry weight of nondeficient, bloom-sampled grape petioles. Research shows that vines having petiole magnesium concentrations of less than 0.25 percent at bloom will typically develop magnesium deficiency symptoms by mid- to late summer. Magnesium deficiency is often observed where vines are grown in soils of low pH (less than 5.5) and where potassium is abundantly available. The likelihood of magnesium deficiency appears to increase when petiole potassium-to-magnesium ratios exceed 5 to 1. Plants grown on soil high in available potassium often express magnesium deficiency even though soil magnesium levels test relatively high.

Assessing the Need for Magnesium Fertilizer

As with most other nutrients, leaf petiole sampling at bloom time can be used to determine the vines’ magnesium status. Tissue analysis results (Table 9.3) coupled with visual observations should indicate whether to apply magnesium.

Correcting Magnesium Deficiency

Magnesium deficiencies can be corrected with either foliar or soil applications of magnesium fertilizers. Foliar application is appropriate to correct a mild deficiency or for short-term correction, but soil application offers a more long-term remedy.

If foliar application is chosen, spray the foliage with 5 to 10 pounds of magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) in 100 gallons of water per acre. This measurement will assure uniform coverage of leaves. Apply the MgSO4 three times at two-week intervals in the post-bloom period. This approach is significantly more effective than waiting until deficiency symptoms are evident in mid- to late summer. Magnesium sulfate can be purchased in a sprayable formulation from fertilizer dealers in 50-pound bags or it can be purchased at drug stores as Epsom salts in smaller quantities. The magnesium sulfate can be mixed with most fungicide or insecticide sprays unless the pesticide label cautions against this combination.

Long-term correction of magnesium deficiencies is achieved by periodic soil application of magnesium-containing nutrients. If the soil pH is also low (less than 5.5), high-magnesium-content limestone (dolomitic lime containing 20 percent magnesium) is the preferred magnesium source and should be applied at 1 or 2 tons per acre. If dolomitic lime is not readily available, then fertilizer-grade magnesium sulfate or other fertilizers containing some percentage of magnesium oxide (MgO) are generally available and sold either in bulk or in bags. Magnesium sulfate is applied at 300 to 600 pounds per acre (50 to 100 pounds of magnesium oxide per acre). To be most effective, magnesium sulfate or magnesium oxide should be banded under the trellis rather than broadcast over the vineyard floor. In small plantings, the fertilizer can be placed in rings 12 to 18 inches from the trunks of individual vines.

Boron

Role of Boron

Boron is an essential micronutrient; very small quantities are required for normal growth and development. Boron has regulatory roles in carbohydrate synthesis and cell division. A deficiency can disrupt or kill cells in meristematic regions of plants (regions of active cell division such as shoot tips). Boron deficiency also reduces pollen development and pollen fertility. Reduced fruit set is thus a common occurrence with boron-deficient vines.

Symptoms and Effects of Boron Deficiency

Boron deficiency symptoms can be easily confused with other vine disorders and must be confirmed by tissue analysis before attempting corrective measures. California literature distinguishes early-season boron deficiency symptoms from symptoms that develop later in the spring or summer. The early-season symptoms appear soon after bud break as retarded shoot growth and, in some cases, death of shoot tips. Shoots can also exhibit a zig-zag growth pattern, have shortened internodes, and produce numerous, dwarfed lateral shoots (Figure 9.5). Those early-season symptoms are thought to be more severe following a dry fall or when vines are grown on shallow, droughty soils; either situation reduces boron uptake.

A second category of boron deficiency develops later in the spring and is marked primarily by reduced fruit set. The nature of the reduced set can range from the presence of a few normal-sized berries per cluster to a condition in which numerous BB-sized berries are also present. The “shot” berries lack seeds and often have a somewhat flattened shape, as opposed to the normal spherical to oval shape. A note of caution: poor fruit set is not necessarily due to boron deficiency. Other factors, such as tomato ringspot virus and poor weather during bloom, can reduce fruit set. Furthermore, the application of boron can lead to phytotoxicity if the boron concentration is already sufficient (Figure 9.6).

Foliar boron deficiency symptoms may accompany the reduced fruit set if boron deficiency is severe. Foliar symptoms begin as a yellowing between leaf veins and can progress to browning and death of these areas of the leaf. Boron is not readily translocated throughout the vine. Thus, the foliar symptoms develop first on the younger, more terminal leaves of the shoot. As with early-season deficiency symptoms, primary shoot tips may stop growing, resulting in a proliferation of small lateral shoots.

Causes of Boron Deficiency

Grapevines are considered to have higher boron requirements (on a dry weight basis) than many other crops. For bloom-sampled vines, petioles containing less than 30 parts per million (ppm) are considered marginally deficient, although clear boron deficiency symptoms may not appear until the boron level drops to 20 ppm or lower. Soil pH, leachability of the soil, frequency of rainfall, and the amount of organic matter in soil affect the availability of boron.

A soil pH of less than 5.0 or greater than 7.0 reduces the availability of boron. Boron is actually very soluble at low soil pH, but in sandy soils the increased solubility, if coupled with frequent rainfall, can lead to leaching of boron from the root zone. Vines grown on sandy, low-pH soils subjected to frequent rainfall are therefore prime candidates to express boron deficiency symptoms.

Topsoils, which generally contain more organic matter than do subsoils, provide vines with the bulk of their boron needs. If the topsoil of the vineyard is eroded, the availability of boron may to be reduced. Furthermore, droughts intensify boron deficiency, probably because the topsoil dries sooner than the subsoil. This drying pattern reduces the vines’ ability to extract nutrients from the topsoil even though moisture and some nutrients can be obtained from the relatively moist subsoil.

Assessing the Need for Boron Fertilizer

The foremost consideration in correcting boron deficiency is to determine whether the vines are actually deficient. Excess boron uptake leads to pronounced leaf burning and leaf cupping (Figure 9.6). Therefore, it is imperative not to apply boron unless it is needed. Routine bloom-time petiole sampling should be used to determine the vines’ boron status.

Correcting Boron Deficiency

If plant boron levels are low, corrective measures can be made in the following season. Confirmed deficiencies are corrected by spraying soluble boron fertilizer on the foliage. Recommendations developed in New York appear appropriate for this region and consist of two consecutive foliar sprays. The first application is made about two weeks before bloom. The second is made at the start of bloom but no earlier than 10 days after the first application was made. Apply ½ pound of actual boron per acre in each spray using enough water to thoroughly cover the flower clusters. It is important not to exceed this rate of application nor to reduce the 10-day interval between consecutive applications. Solubor 20 is a borate fertilizer containing about 20 percent actual boron. Thus, 2.5 pounds of this material should be applied per acre to provide the ½ pound of actual boron needed.

The water-soluble packaging of certain fungicide and insecticide formulations reacts with boron to produce an insoluble product. Therefore, boron should not be tank mixed with pesticides packaged in that manner nor with any pesticide that cautions against boron incompatibility. Foliar application of boron is a temporary solution but has the advantage of avoiding a possibly excessive soil application. With proper calibration, boron can be applied in soluble form to the soil with irrigation equipment, with an herbicide sprayer, or with an airblast sprayer before bud break or after defoliation in the fall. Soil applications can be made at any time of the season, but their effect will be delayed until the boron reaches the root zone. Dry formulations of boron, such as borax, are difficult to apply uniformly to the soil because very small quantities are used.

Other Nutrients

Other essential elements are generally found at or above sufficiency levels in North Carolina vineyards and are currently of minor concern. Occasionally, tissue analyses will show excessive levels of certain micronutrients such as iron, zinc, or copper. Those elevated levels are usually due to residues of fungicides containing those elements, not to excessive root absorption. Achieving and maintaining adequate vine nutrition is but one component of sound vineyard management. If a nutrient is deficient, vines will not achieve optimal yields and fruit quality, and maximum returns on the vineyard investment will not be realized. Good vine nutrition starts in the preplanting phase and extends through the productive years of the vineyard. It requires recognition of visual deficiency symptoms and the use of specialized soil and plant tissue analysis techniques. Ideally, fertilizers should be applied when needed on a maintenance schedule rather than waiting until a nutrient deficiency is observed. The producer must also be willing to apply lime and other fertilizers efficiently where they are needed. Considering the low cost-to-benefit ratio of most fertilizers, that should not be a difficult management decision.

Additional Reading

Christensen, L. P., A. N. Kasimatis, and F. L. Jensen. 1978. Grapevine Nutrition and Fertilization in the San Joaquin Valley. Univer- sity of California Division of Agricultural Sciences, Publication No. 4087. 40 pp.

Winkler, A. J., J. A. Cook, W. M. Kliewer, and L. A. Lider. 1974. General Viticulture. Univer- sity of California Press. Berkeley, California. 710 pp.

Soil and Plant Tissue Testing Services

Call the laboratory or visit the Agronomic Services Page on the North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services website to determine current pricing and submission information.

Plant Analysis Laboratory

NCDA&CS

Mailing address: 1040 Mail Service Center

Raleigh, NC 27699-1040

Physical address for samples via UPS or FedEx:

4300 Reedy Creek Rd. Raleigh, 27607-6465

phone: 919-733-2655

ax: 919-733-2837

Soil Analysis

Agronomic Division

Soil Testing Section

1040 Mail Service Center

Raleigh, NC 27699-1040

Physical address for samples via UPS or FedEx:

NCDA&CS Agronomic Division Soil Testing Section

4300 Reedy Creek Rd. Raleigh, 27607-6465

phone: 919-733-2655

Publication date: Feb. 28, 2007

Reviewed/Revised: Aug. 11, 2025

Other Publications in The North Carolina Winegrape Grower’s Guide

- Chapter 1. Introduction

- Chapter 2. Cost and Investment Analysis of Chardonnay (Vitis Vinifera) Winegrapes in North Carolina

- Chapter 3. Choice of Varieties

- Chapter 4. Vineyard Site Selection

- Chapter 5. Vineyard Establishment

- Chapter 6. Pruning and Training

- Chapter 7. Canopy Management

- Chapter 8. Pest Management

- Chapter 9. Vine Nutrition

- Chapter 10. Grapevine Water Relations and Vineyard Irrigation

- Chapter 11. Spring Frost Control

- Chapter 12. Crop Prediction

- Chapter 13. Appendix Contact Information

- Chapter 14. Glossary

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.