Applying swine manure to forestland that needs nitrogen and phosphorus can help swine producers manage waste and put valuable nutrients to work for forest owners.

Background

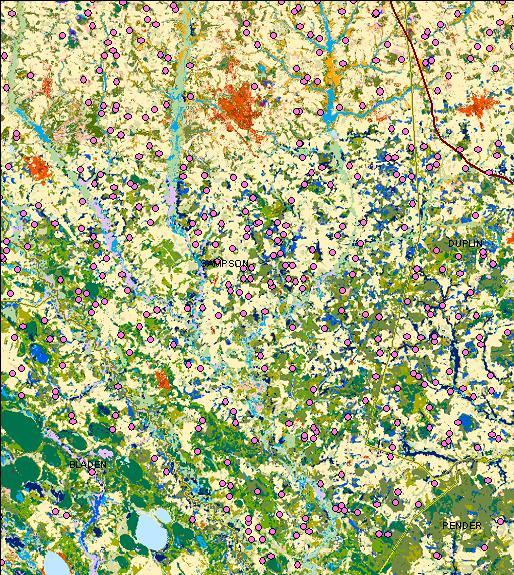

Forest soils in the southern United States are almost universally deficient in nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P). These soils often exist near animal feeding operations that produce large surpluses of N and P in animal manure (Figure 1). North Carolina has 30 counties where more P is produced in animal manures than can be assimilated by all the cropland and pastureland in those counties, and 7 counties where more N is produced than can be assimilated (Gollehon et al., 2001). These analyses did not consider forestland. It appears that forestland will have to be used – in addition to available cropland and pastureland – if land application is to continue to be the usual method by which North Carolina swine producers manage animal waste nutrients and retain their prominent position in U.S. animal agriculture. Thus, great potential exists to develop mutually beneficial “win-win alliances” between swine producers and forest owners by putting the N and P in animal manures to work in nearby forests.

North Carolina has more than 8 million acres of forestland (60 percent of its total land area), almost 90 percent of which is privately owned. That includes more than 2.5 million acres of pine plantations, of which about 100,000 acres are fertilized – usually with synthetic chemical fertilizers (granular urea and diammonium phosphate). Plantations of hardwood trees are much less common in North Carolina and employ essentially no routine fertilization.

Fertilization is well known to increase the growth of a wide variety of marketable forest products and can enhance ecosystem services. Shorter-rotation forest crops, such as nursery planting stock or woody biomass species, and annual crops such as pine straw can also benefit from fertilization of pine forests with animal manure nutrients.

This publication is based on a research project designed to investigate factors that make fertilizing forests with animal manures successful in North Carolina. Our approach was to capitalize on the practical experience and perspectives of animal producers and forest owners and managers through interviews with swine producers who have used or considered using animal manures to fertilize forests. Sometimes the swine producers we interviewed were also owners of forest stands to which swine manure nutrients were being applied to increase yields of marketable forest products.

Southern pine plantations were the most common type of forest currently being used for fertilization purposes by our interviewees. The amounts of swine manure nutrients being used usually involved applications of moderate amounts of swine lagoon liquid (typically 50 to 100 pounds N per acre).

There are about 2,300 permitted swine feeding operations in North Carolina, of which about 900 qualify as large concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs). The total amount of swine manure (wet plus dry excretions) produced in North Carolina is estimated to be about 28 million tons a year. Swine operations are concentrated in North Carolina’s southern coastal plain.Based on analyses from 1996 to 2006, swine lagoon liquid had average plant-available nutrient analyses per 1,000 gallons of about 1.8 lb N, 1 lb P2O5, and 5.4 lb K2O (Cleveland et al., 2007). Statistics from 1999 to 2009 indicate that the nutrient content of swine lagoon sludge was greater than swine lagoon liquid but also much more variable per 1,000 gallons: 5.8 to 10 lb N, 12.6 to 35.5 lb P2O5, and 5 to 7.7 lb K2O (B. Cleveland, personal communication).

Benefits of Swine Manure Nutrients in Forest Fertilization

Using swine manure nutrients in forest fertilization offers benefits to swine producers and forestland owners. The animal producers we interviewed provided the quotes noted below.

- Offers additional land for useful nutrient application. This may be especially important if P requirements become more of an issue so that land requirements for application increase. Our analysis shows that 90 percent of the swine operations in Sampson County have pine plantations within a 5-mile radius of their farms.

- Allows a longer window of time during the year for application. Forests can have nutrients applied to them during periods when some pasture or row crops cannot be fertilized; the application window for pine trees is from November through February. As one interviewee noted, “I would be lost without my pine trees. There's always some times of the year that you can't pump on cropland, so if you have trees you don't worry so much about getting into difficult positions.”

- Provides an alternative to fully clearing a site for pasture or row crops, if establishing a new application site. “[The] Real benefit of this practice is that by bulldozing a lane through an existing forest site, you get 6 to 7 acres to apply to, instead of needing to clear the whole area for grass.”

- May be an especially useful option during sludge clean-out. Interviewees offered several comments on this benefit: “As you need to clean out lagoon and use sludge, there is less water involved and it is more transportable, more nutrient dense, especially P – that might work better for forests.” “If a farmer needed to remove sludge, and trees were 5 miles away versus cropland 10 miles away, it would pay for itself to apply to trees.” “Might make sense for forest owners to set up forest stands for eventual sludge application.”

- Avoids expense of yearly harvests of annual crops. “If the forests will take it, you wouldn’t have the expense of harvesting hay or rye.”

- Increases growth of a valuable crop. Most southern pine plantations are limited by nutrient availability. Long-term research by the Forest Nutrition Cooperative formed by NC State University, Virginia Polytechnic Institute, and Universidad de Concepción in Chile indicates that most intermediate-aged (8- to 20-year-old) southern pine stands show good growth response to fertilization with N and P. The typical wood volume growth increase is 30 percent over 8 years and can be as high as 100 percent.

Addressing Obstacles to Using Swine Manure Nutrients in Forest Fertilization

The swine producers we interviewed perceived several obstacles to using manure to fertilize forests. Potential ways to overcome the obstacles were discussed.

Concern about delivering manure nutrients into forest stands. Forest fertilization systems have successfully utilized the same spray equipment traditionally used on agricultural crops, such as solid set irrigation systems, hose and reel, and honey wagons. Ideally, a forest stand can be planted at a spacing that will allow the equipment required to spray liquid or spread sludge to pass through the stand. One interviewee noted: “You should tailor planting of trees to size of equipment needed to spray.” Thinning to remove rows at an interval such as every fifth row in a stand previously established at a smaller spacing or clearing lanes in naturally regenerated stands is also used as a way to provide access through an entire rotation. A producer who applies swine manure to forests described the biggest obstacle as “laying pipework and hydrants, getting lanes set up. Other than that, it’s no different than pumping on a field crop.”

Lower rate of nutrient application than pasture or row crops. Interviewees commented about application rate and nutrient amounts: “Low application rate to trees compared to row crops and grass crops.” “As for using trees for sludge application, I don't think trees could handle the amount of nutrients in sludge.” The Natural Resources Conservation Service nutrient application rate guidelines for forests are lower on an annual basis than most agricultural crops, although the revised guidelines allow a relatively large rate (300 lb/acre) to be applied every fifth year. Sufficient forestland should be identified to ensure appropriate application rates based on the nutrient content of swine liquid or sludge, either as an adjunct to pasture and cropland or as a primary application site. Most forest soils have not been subjected to repeated nutrient applications, and so tend not to have accumulated P. NC State University and local Cooperative Extension agents in your county can assist with fertilizer recommendations.

Logistical and operational issues. Swine producers expressed concerns about equipment pressure and access: “Problem with using hose and reel to land-apply waste–too high pressure can strip bark off trees.” “Closing of application lanes in trees after ice storms.” Spraying an appropriate distance from trees and reducing pressure at the spray nozzle can alleviate the problem of bark stripping. Application lanes can be managed for access, with weed control, understory or brush removal, or cover crop planting.

Potential for accumulation of metals. Heavy metals, especially copper and zinc, are used in some feed mixtures for swine. Although copper and zinc are required micronutrients for plant growth, excessive amounts can be toxic. Repeated applications of manures could cause metals to build up in soils and potentially runoff to waters. Metal accumulation may be less of a problem in forest soils because most have not been previously fertilized with manures and typically have low concentrations of micronutrients. Soil testing should be used to determine soil concentrations of metals or other elements and appropriate application rates.

Official Guidelines for Land Application of Manure in Forest Stands

Animal rearing operations in North Carolina are subject to state and federal environmental regulations. The North Carolina Regulations for Wastes Not Discharged to Surface Waters require any swine rearing operation with more than 250 head to apply for and operate under a general permit. Some farms are required to operate under a federal National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit. Both permits require farms to develop an approved nutrient management plan designed to maximize beneficial use of manure nutrients and minimize nutrient losses from the farm. Appropriate manure application rates are determined by realistic yield expectations (RYE) of a specific crop, characteristics of the specific soil, and the manure’s nutrient content.

NRCS Nutrient Management Standard (Code 590) and Waste Utilization Standard (Code 633) provide technical guidelines for manure application to forest plantations in addition to croplands (see the NRCS Field Office Technical Guide). According to these NRCS standards for North Carolina, which are based in large part on guidelines provided by the NC Interagency Nutrient Management Committee, up to 60 lb of plant available nitrogen (PAN) per acre per year can be applied on pine forestland, except for longleaf pine stands – where 30 lb PAN/acre/year is the recommended limit. On hardwood forest stands suitable for organic fertilizers, application rates should not exceed 80 lb PAN/acre/year.

Higher N application rates on forestland may be approved by technical specialists designated by the NC Soil and Water Conservation Commission in situations where concentrated single waste applications may be necessary, such as lagoon closures or lagoon sludge management, or in cases designed to meet a specific forestry nutrition prescription in an approved forest management plan. In cases where concentrated single applications are needed, the total application rate should not exceed 300 lb PAN/acre. Such single applications should not be repeated more frequently than every fifth year, or every tenth year in longleaf pine, in order not to exceed recommended average annual N application rates. Annual soil tests, taken at a soil-surface-to-6-inch sampling depth, must be completed in pine forest application areas to help determine the potential for P leaching. If soil test agronomic P indices are above 50, then no additional animal manure waste application should occur on forestland. A phosphorous loss assessment (PLAT) is not needed for forestland receiving animal manures. North Carolina and NPDES permitted animal operations must include all areas where animal manure nutrients are applied in a certified animal waste management plan.

Negative impacts to streams, wetlands, and riparian buffers must be avoided when applying swine waste materials, and appropriate application setbacks must be observed. At a minimum, no waste materials should be applied:

- In wetlands and in poorly drained or organic soils

- Within 100 feet of a well

- Within 200 feet of a dwelling other than those owned by the producer

- Within 75 feet of a residential property boundary

- Within 75 feet of an intermittent, seasonal, or perennial stream or river other than an irrigation ditch or canal

North Carolina and NPDES permitted animal feeding operations are required to observe setbacks set forth by their respective permits and North Carolina’s regulatory requirements.

Some native plants adapted to low fertility sites are able to compete with introduced species because of limited forestland fertility. Applying organic materials may increase the potential for introducing invasive plants, enhancing their viability, or both. Because the effects of increased fertility in native plant understory are not well understood, application of waste materials in forestland where the health of native plant communities is a resource concern should be closely monitored for negative impacts. Any increase in noxious or invasive plant species in native plant communities should be noted and considered when fertilizing trees with animal waste materials.

Description of a Useful GIS Database

An important part of our research project with forest owners and swine and poultry producers was development of a geographic information system (GIS) database that contains general information for much of the state and more detailed information for the following nine North Carolina counties: Bladen, Duplin, Moore, Montgomery, Onslow, Pender, Richmond, Sampson, and Wayne. The database incorporates the following information: swine operations (2003); 5-mile grid of poultry farms (2007); highways, streets, municipalities, county boundaries, major water bodies, major hydrography (streams), and river basins for North Carolina; detailed hydrography and detailed water bodies for the Cape Fear, Lumber, Neuse, White Oak, and Yadkin River Basins; land use and land cover classes; and parcels, soils, and aerial photography (2007) for the study counties.

As an example of a product from the database, the map Figure 2A indicates the parcels of land within a 5-mile radius of a swine finishing farm owned by a swine producer (the circle is centered on the farm parcel). The data base identifies land areas that fall into the land cover categories coniferous cultivated plantation or coniferous regeneration. Figure 2A shows more than 11,500 acres of coniferous forest areas; a similar calculation for a 1-mile radius (Figure 2B) shows more than 500 acres. Calculations can be made for different land cover types and different radii. Land parcel ownership information is available to assist in connecting swine producers and nearby forest landowners. Similar information can be found by contacting local offices of your county tax assessor, N.C. Cooperative Extension, NC Forest Service, USDA Farm Service Agency, or Natural Resource Conservation Service.

Economics

The economics of transferring swine manure to forest stands is similar to that for crops. In many cases, swine producers are also forest owners, and thus have associated land that is forested and can be used for manure application. In some cases, swine producers lease land for manure application to trees. Alliances between producers of nutrients (animal producers) and potential receivers of nutrients (other landowners) are usually developed by personal contact. If a farmer wants to convert existing cropland to forest trees or is seeking financial help with manure transportation costs, several incentive programs exist that may provide cost-sharing:

NC Agricultural Cost Share Program (NCACSP)

The Agriculture Cost Share Program for Nonpoint Source Pollution Control utilizes legislative funds administered by the Soil and Water Conservation Commission to assist farmers in best management practices that reduce the input of agricultural nonpoint source pollution into North Carolina’s waters. The program currently includes 33 counties and can provide up to 75 percent of the cost of a practice up to a maximum of $75,000 per year. Some of the practices that qualify for assistance include cropland conversion to permanent vegetation, closure of lagoons, riparian buffers or equivalent controls, and animal waste management systems and applications. The forest stands established are expected to remain for 10 years.

Conservation Reserve Program (CRP)

CRP is offered by the Farm Service Agency (FSA), in partnership with NRCS, as an option for converting eligible erosive cropland and conservation priority areas to trees. CRP gives eligible producers with land the opportunity to plant trees (can be pines or hardwoods) at a 50 percent cost-sharing rate; in addition, FSA will pay the producer a rental rate based on the soil type for a period of 10 to 15 years. CRP is a competitive program that is available only during designated signup periods.

Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP)

CREP is a joint effort of the NC Division of Soil and Water Conservation, NC Clean Water Management Trust Fund, Ecosystem Enhancement Program, and FSA to address water quality problems of the Neuse, Tar-Pamlico, and Chowan river basins as well as the Jordan Lake watershed area. Under this program, some land management may be restricted.

Other Information Resources

NC Interagency Nutrient Management Committee

Forest Productivity Cooperative

NC State University Hardwood Cooperative

References

Blevins, D. 1994. Pinestraw raking and fertilization impacts of the nutrition and productivity of longleaf pine. M.S. Thesis. Raleigh: NC State University, Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources, College of Natural Resources. 65 pp.

Blevins, D., H. L. Allen, S. Colbett, and W. Gardner. 1996. Nutrition Management for Longleaf Pinestraw. Woodland Owner Notes 30. Raleigh: N.C. Cooperative Extension, NC State University. 8 pp.

Clark III, A., B. E. Borders, and R. F. Daniels. 2004. Impact of vegetation control and annual fertilization on properties of loblolly pine wood at age 12. Forest Products Journal 54(12):90-96.

Cleveland, B. R, M. McGinnis, and C. E. Stokes. 2007. Improving agricultural productivity & environmental quality. Raleigh: NC Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Agronomic Division. 2 pp.

Cowling, E., C. Furiness, L. Allen, T. Fox, R. Abt, K. Zering, R. Campbell, and L. Fetterman. 2005. Turning waste into profits: exploring the forest alternative. In G. B. Havenstein (ed.), The Development of Alternative Technologies for the Processing and Use of Animal Waste (pp. 148–157). Proceedings of the 2005 Animal Waste Management Symposium, October 6 – 8, 2005, Research Triangle Park, NC. Raleigh: NC State University, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. ISBN 0-9669770-3-3.

Environmental Impact (RC&D), Inc. 2003. Longleaf Pine Ecosystem/Animal Waste Management Research, Demonstration, and Education Project, Phase II – Final Report June 1998 through December 2002. Aberdeen, NC: Environmental Impact.

Fox, T. R., H. L. Allen, T. J. Albaugh, R. Rubilar, and C. A. Carlson. 2007. Tree nutrition and forest fertilization of pine plantations in the southern United States. South. J. Appl. For. 31(1):5-11.

Furiness, C. S., and E. B. Cowling. 2005. Turning Waste into Profits: Exploring the Forest Alternative. In G. B. Havenstein (ed.), The Development of Alternative Technologies for the Processing and Use of Animal Waste (Virtual Farm Tours). 2005 Animal Waste Management Symposium, October 6 – 8, 2005, Research Triangle Park, NC. Raleigh: NC State University, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. ISBN 0-9669770-3-3.

Gollehon, N., M. Caswell, M. Ribaudo, R. Kellogg, C. Lander, and D. Letson. 2001. Confined animal production and manure nutrients. Agriculture Technical Bulletin 771. Washington, DC: USDA, Economic Research Service. 39 pp.

Acknowledgements

This publication was developed in consultation with the NC Interagency Nutrient Management Committee and the current leaders of the university-industry Forest Nutrition Cooperative at NC State University, Virginia Polytechnic Institute, and the Universidad de Concepción in Chile. Funding for this project was provided by the Golden LEAF Foundation and the Kenan Institute for Engineering, Technology and Science at NC State University.

Publication date: March 20, 2019

Reviewed/Revised: Feb. 15, 2024

AG-740

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.