Introduction

Your sleep is disturbed by what sounds like scratching and digging in the walls, but it's hard to place. The next morning you awake to find the bottom corner of your favorite snack box chewed through; crumbs spread around the kitchen. When you reach into your silverware drawer for your favorite spoon your eyes land on a small black “package” left neatly on the spoon’s surface. These signs and others point towards a common culprit, who has a long history of cohabitation with humans, and has even become the face of some of the biggest corporations: the mouse. Despite its cute appearance it is far from the ideal roommate; passing unnoticed throughout your room, pooping and peeing on sills and spoons alike, and pilfering through your pantries. Aside from these nuisance behaviors, mice serve as the host for a variety of disease-transmitting arthropods, including ticks and fleas. When faced with a one off mouse invader, or an infestation, it is critical to begin with an understanding of mouse biology and behavior to inform your management strategy. In this publication we discuss the history of human-mouse interactions, mouse biology and life cycle, and intricacies and seasonality of mouse behavior. Read on to learn more about this cuddly and conniving pest, but don’t expect it to sing you any catchy songs.

History & Risks to Humans

Our history alongside the mouse is a long one - with the earliest evidence of mice as a pest of humans dating to nearly 15,000 years ago. This coincided with the emergence of more agrarian lifestyles among early humans, where communities settled down and began to store food in order to survive the winter. Today’s small and furry pest still resided exclusively outdoors at this point, but quickly discovered that this new and predictable food source allowed better chances of survival through the long winter months. Better yet, they could reside indoors away from common predators (ex. hawks, owls, other mammals). While some mice may have established themselves indoors, several other species of mice still occasionally find their way inside to exploit those critical sources of food and shelter. There are three common species of mice that invade built structures in the United States: the house mouse (Mus musculus) (Figure 1), deer mice (Peromyscus spp.) (Figure 2), and field mice (Apodemus spp.) (Figure 3). Each of these groups of mice can carry a host of pathogens, cause damage to structural components, and will readily raid your pantry. Below we discuss some of the health threats associated with invading mice.

Mouse-Associated Disease

A vast array of communicable diseases can be contracted through either direct or indirect contact with mice or their bodily fluids and feces. While a single mouse, given it’s small size, may seem like a small issue - mice can produce anywhere from 50-75 droppings per day. Their saliva and urine, as well as direct contact with the rodent can also spread disease. Some of the most common and concerning diseases include:

-

Hantavirus: a virus spread most commonly through contact with deer mice, but can be contracted from other rodents, which presents in the form of two geographically different syndromes. In the western hemisphere, including in the U.S., the virus can cause hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS), a severe and potentially deadly disease of the lungs. Common symptoms include fever and fatigue, and roughly 10 days after exposure in severe cases the lungs begin to fill with fluid, leading to coughing and shortness of breath (CDC).

-

Salmonella: a bacteria contracted from consuming contaminated food, or from using contaminated utensils. Can be contracted from various mice. Infection with this bacteria results in salmonellosis, which can lead to watery diarrhea, vomiting, nausea and other symptoms (CDC).

-

Tularemia: a bacterial illness caused by the bacterium Francisella tularensis, and often contracted from contact with infected animals, especially rodents (mice). Symptoms vary greatly depending on the method of bacterial entry into the body, but can range from ulcers and swelling of lymph nodes to severe cough and shortness of breath (CDC).

Dangerous Hitchhikers

Beyond the disease spread directly from contact with mice and their fluids, a host of diseases are indirectly transmitted by mice - via the arthropod pests that live on the mice themselves. The most common of these pests are ticks, mites, fleas, as well as mosquitoes which feed on mice and then feed on unsuspecting humans. There is an even broader array of potential mouse-associated arthropod-vectored diseases - a full list can be found on the CDC website - but a few diseases of critical importance are listed below:

-

Lyme Disease: a bacterial infection common throughout much of the U.S. and transmitted through the bite of the blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis), also known as the deer tick. A wide range of symptoms are possible with Lyme disease, including fever, rash, partial paralysis, arthritis, and others (CDC).

-

Flea-borne Typhus (Murine Typhus): a bacterial infection which occurs when humans or animals are exposed to infected feces of the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis) following a flea bite. Typically, infected feces is scratched into the open bite wound, leading to infection (CDC). Read more about fleas in our factsheet, Biology and Control of Fleas.

-

Scrub Typhus: a bacterial disease caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi, and spread through the bite of infected chiggers. Symptoms can include fever, chills, headache, and even psychological impacts (CDC).

Life Cycle & Reproduction

Behavior, Communication and Social Structure

Mice are mainly nocturnal, although at some locations, daytime activity may be observed. They have poor eyesight, with little to no color vision, relying more on their hearing and excellent senses of smell, taste and touch to navigate their environment. Their hearing is superior and extends into the ultrasonic range – sound waves that humans cannot hear. They have an excellent sense of touch and use their whiskers (vibrissae) to navigate and explore.

In general, mice have variable social structures, ranging from a single male and one to several adult females and juveniles, to larger, more social aggregations. Female mice tend to live in extended family groups where they share the nest and the responsibilities of raising offspring. Within these structures and beyond, mice primarily rely on pheromones for social communication. These pheromones are produced by glands located near their genitals and are also present in their tears and in the urine of male mice. They have a musky odor detectable by humans, and the odor can be one potential sign of mouse activity.

Mice can also communicate vocally, using a range of sounds for different purposes. They produce soft “chittering” and squeaking noises to each other in their nests, and during times of fear or distress. These sounds are audible to humans. Some songs are produced exclusively by males and others only by females.

Feeding & Habitat

Mice are omnivorous with a varied diet but prefer seeds and grain. They readily sample new foods and are considered "nibblers," sampling many kinds of food items they may encounter in their environment. Foods high in fat, protein, or sugar may be preferred even when grain and seed also are present. A single mouse eats only about 3 grams of food per day (8 pounds per year). However, mice destroy considerably more food than they consume because they nibble on many different foods and discard partially eaten items. Mice can get by with little or no free water, although they readily drink water when it is available, as they are able to highly concentrate their urine.

Mice can be found living in woodpiles, underbrush, tree hollows, in piles of debris, in sheds, barns, crawl spaces, garages, and other places near a source of food. If there’s no other suitable shelter, mice can dig and may burrow into the ground in fields or around structures. Mice build nests using soft materials, such as finely shredded paper or cloth (Figure 4). A nest will have several access points, not only as a convenience for entering but also for providing a quick exit if a predator comes around.

House mice (Mus musculus) are more acclimated to living around humans than deer- and field mice, and will readily move into our homes and offices. Some spend their entire lives in a building, where they may live in walls, under major appliances, in storage boxes and drawers, or upholstered furniture.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

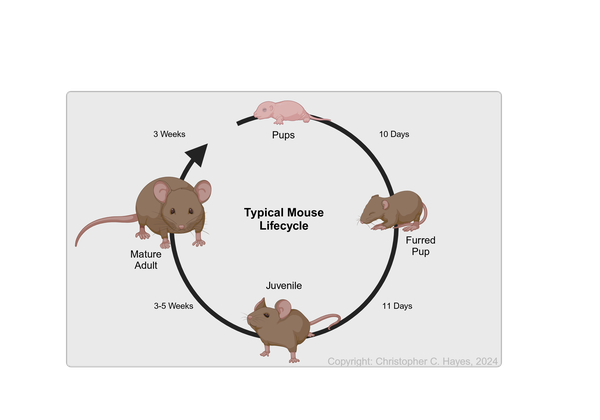

Mice have short generation times; gestation lasts approximately 3 weeks, and they are sexually mature at 6-8 weeks of age (Figure 5). Once mature, mice may breed year-round, with a female having 5-10 litters per year. To find a mate, female mice produce scents that attract the attention of males, often prompting the males to produce ultrasonic vocalizations. While both male and female mice can emit ultrasonic sounds, males produce most of these vocalizations. These ultrasonic vocalizations play a significant role during courtship and mating.

One pregnant, the average litter size is 10-12 pups, but can vary depending on mouse age, resource availability, and season. Mouse pups weigh between 0.5-1.5 grams at birth, are blind and deaf, and rely on their whiskers to navigate their environment. They are fully furred after 10 days, and by 14 days old, their eyes and ears are open, and their incisor teeth are visible. Pups are weaned and start to leave the nest at approximately 3 weeks of age, with a weaning weight of about 10-12 grams (Figure 5). The average lifespan for structure invading mice ranges, but generally is around 12-18 months, though survival to the upper range is rare in the wild. Mice face numerous threats, including predation by a wide array of animals such as birds of prey, snakes, and larger mammals, and are extremely vulnerable to environmental hazards (severe weather), food scarcity, and human activity.

If you are interested in learning more about mice, and about structure invading mouse surveillance and management check out our publication here!

Disclaimer: Any commercial products mentioned in this publication serve as examples only, and do not represent endorsements of the products by any entities associated with this publication

Publication date: Dec. 12, 2024

The use of brand names in this publication does not imply endorsement by NC State University or N.C. A&T State University of the products or services named nor discrimination against similar products or services not mentioned.

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.