The Need for Bounce Forward Tourism Resilience

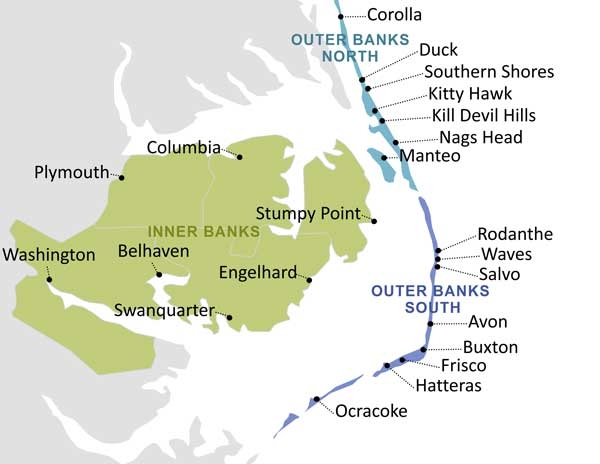

North Carolina’s Outer Banks (OBX) (Figure 1) have long been a popular tourist destination because of their unique combination of cultural and natural resources (Seekamp et al. 2023). The remoteness and natural beauty of the region drove record visitation numbers during the COVID-19 pandemic, and high levels of visitation have been sustained (Outer Banks Visitors Bureau n.d.). This heightened popularity further establishes tourism as an economic driver for the region. While demand for travel experiences in these coastal communities rises, increasing coastal hazards (including storms, flooding, sea level rise, and erosion) are threatening the sustainability of the OBX tourism industry.

OBX communities such as the villages of Ocracoke (Hyde County) and Hatteras (Dare County) are particularly vulnerable to coastal hazards due to their geographic location. OBX communities regularly contend with hurricanes, flooding, and high winds. Storms have become part of life for multigenerational residents, newcomers, nonresident property owners, and tourists. For example, Hurricane Dorian severely affected the communities of Ocracoke and Hatteras in September 2019. In Ocracoke, Dorian caused rapid sound-side flooding, a storm surge of 7 to 8 feet, and winds of 90 miles per hour. Most Ocracoke residents chose not to evacuate prior to Dorian because they did not anticipate major impacts, but they were trapped on the island as the floodwaters rose (WRAL 2019). Although the damage was not as severe on Hatteras Island, residents still had to deal with flooding, high winds, power outages, and transportation disruptions, including the closure of the main route, NC Highway 12.

Storm-related flooding, like what Dorian caused in Hatteras and Ocracoke, is common in the OBX. Yet, sea level rise is resulting in an increased prevalence of nuisance flooding even on sunny days. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates that with only 1 foot of additional sea level rise, most of the OBX would be underwater. Such changes create coastal hazards that typically would happen only during major storm events but now happen more regularly and are expected to increase over time with climate change (Glavovic et al. 2015).

Coastal hazards threaten the tourism industry in the OBX by disrupting transportation flows (for example, road closures and canceled ferry services), changing the visual appeal of natural areas (for example, eroded beaches), and destroying infrastructure like bridges, lodging, and restaurants (Seekamp et al. 2023). A disruption in the tourism industry is problematic, as OBX communities depend on tourism as their main economic driver. In 2023, tourism accounted for $2.7 billion in spending in OBX counties (Currituck, Dare, and Hyde) and fueled nearly 15,500 jobs (Visit North Carolina n.d.). Small-scale tourism businesses are keystones in these communities, serving as the primary employers and revenue generators. Therefore, tourism industry recovery decisions affect the resilience of all community members.

Resilience has traditionally been identified as the ability to “bounce back” from a catastrophic event (Berke and Smith 2009; Cutter et al. 2008). For disaster-affected communities, bouncing back is interpreted as recovery and a return to “normal” functioning. However, resilience requires more than bouncing back; it also requires “bouncing forward” (Bogardi and Fekete 2018). Bouncing forward is defined as being able to prepare for anticipated disasters, adapt to changing conditions, and withstand and recover rapidly from disruptions (U.S. Department of Homeland Security 2016). Proactively planning and preparing for current and future risks from coastal hazards will help minimize loss of life and damage to personal property, businesses, and natural resources while supporting efficient response and recovery (Finn 2019). Therefore, bouncing forward will help community members and tourism business owners achieve the economic stability needed for a more sustainable, vibrant future.

Understanding “Bounce Back” Versus “Bounce Forward” Recovery Decisions by OBX Tourism Stakeholders

Fostering bounce forward resilience in tourism-dependent coastal communities requires understanding the factors that motivate communities and their members to cope with natural disasters and how these factors influence recovery decisions (Albright and Crow 2021; Cox and Perry 2011). Previous research indicates that social cohesion, place attachment, and risk perception (Table 1) play an important role in the recovery decision-making process (Bonaiuto et al. 2002; Townshend et al. 2015).

| Concept | Definition | Relation to Resilient Communities |

|---|---|---|

| Social Cohesion | The strength of relationships and sense of solidarity among individuals in a community and across communities (Townshend et al. 2015) | Cohesive communities allow individuals to receive warnings, undertake disaster preparation, locate shelter and supplies, and obtain immediate aid and initial recovery assistance (Hawkins and Maurer 2010). |

| Place Attachment | The emotional bonds between a person and a geographic location or how strongly someone is connected to a place (Hernández et al. 2020) | Place attachment increases people’s willingness to act and demand a greater say in place management and recovery initiatives (Burley et al. 2007). |

| Risk Perception | A subjective judgment of the severity of a risk and possible negative consequences the risk could bring with it (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction 2013) | People with heightened risk perceptions tend to be more willing to carry out proactive behaviors (for example, applying flood mitigation measures) (Covello 2003). |

To understand how social cohesion, place attachment, and risk perception are impacting the bounce back versus bounce forward recovery decisions of tourism stakeholders in the OBX following Hurricane Dorian, our research team explored the following questions through interviews with tourism stakeholders in Ocracoke and Hatteras:

- What recovery decisions did tourism stakeholders in Ocracoke and Hatteras make after Hurricane Dorian?

- What are the links between perceptions of social cohesion and recovery decisions?

- What are the links between perceptions of place attachment and recovery decisions?

- What are the links between risk perceptions and recovery decisions?

- What are the differences in recovery decisions made by tourism stakeholders in the two communities (Ocracoke and Hatteras)?

Methods

We interviewed 26 tourism stakeholders in the tourism-dependent communities of Ocracoke (n=12) and Hatteras village (n=14) about their Hurricane Dorian recovery decisions. These stakeholders represented tourism business owners (n=19), nonresident property owners (n=5), and workforce members (n=2). Participants were asked about their length of residency, social cohesion in the community, attachment to the place, and risk perceptions. Interviews were analyzed, and participants were grouped into the following categories: (a) length of residence (newcomer [<2 generations], multiple generations [2–3 generations], or islander [3+ generations]); (b) evidence of within or across community cohesion; (c) evidence of baseline or elevated attachment to the place; and (d) levels of risk perceptions (not high or high) (Table 2). In addition, the stakeholders’ bounce back and bounce forward decisions were documented and examined to determine whether their decisions were personal (for example, elevating a house) or focused on their business (for example, keeping business open later after the tourist season) or community (for example, helping neighbors clean up). The research team members participated in debriefing sessions together to discuss the themes and synthesize the results.

Evidence of Tourism Stakeholder Recovery Decisions

The personal and business bounce back decisions that participants made were often related to a perceived need to “return to normal” (for example, wanting to recover quickly, to open their business back up as soon as possible, or to make their house livable again). Specific bounce back recovery decisions, such as rebuilding and keeping businesses open, were often made quickly and centered around the idea that one should move forward and not dwell in the past. The different stakeholder groups were very supportive of one another in the immediate recovery (for example, nonresident property owners shared their houses with full-time residents whose homes were destroyed). Mutual support was also evident across communities, as Hatteras residents supported Ocracoke residents who were overwhelmed by the extensiveness of storm damage (for example, Hatteras residents traveled to Ocracoke with tractors and trailers to help clean up) (Table 3).

Bounce forward decisions made by participants included actions that would protect themselves (for example, evacuation) and their personal property (for example, taking vehicles out of potential flooding zone); decrease potential damage (for example, protecting house with sandbags and boarding windows); and promote an efficient recovery from future events (for example, obtaining insurance). Business owners may also make decisions such as encouraging guests to evacuate or securing inventory before hurricanes hit. Participants also made bounce forward decisions that factored in the long-term sustainability of their business (for example, taking their business online or developing an adaptive business plan), home (for example, elevating their house), and community (for example, lobbying to keep the community closed to tourists longer) (Table 4).

Key Findings

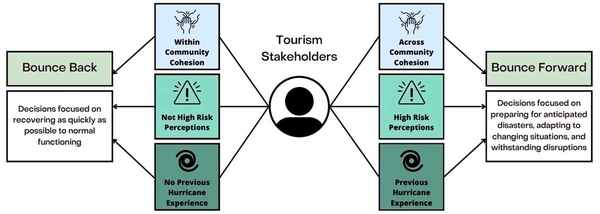

This study examined social cohesion, place attachment, and risk perception to understand what influences tourism stakeholders to make bounce forward recovery decision-making. Figure 2 illustrates the patterns that were revealed in both bounce back and bounce forward decision-making:

-

More bounce forward decisions were made by (a) participants who reported social cohesion across communities, (b) participants with heightened risk perceptions, and (c) participants with prior hurricane experience.

-

More bounce back decisions were made by (a) participants who reported social cohesion within communities, (b) participants whose risk perceptions were not high, and (c) participants without prior hurricane experience.

-

Place attachment was not related to the type of recovery decisions made, as all the participants had a comparable baseline level of place attachment.

Recommendations for Advancing “Bounce Forward” Resilience for Tourism in the Outer Banks

Encouraging more bounce forward decision-making by OBX tourism stakeholders will help communities like Ocracoke and Hatteras build a more sustainable future. To support bounce forward decision-making in the tourism industry, we recommend that tourism stakeholders work together to achieve the following goals.

-

Establish and foster connections with all tourism stakeholders within communities in the Outer Banks, including nonresident property owners, to ensure that resources for efficient recovery and building resilience (for example, supplies, help with clean-up, and temporary housing) are accessible for the entire tourism industry. Local destination marketing or management organizations and community leaders (for example, North Carolina Cooperative Extension centers and business support organizations) can help facilitate opportunities to establish and foster these connections (for example, through annual resilience-focused meetings and workshops).

-

Expand relationships among tourism stakeholders across communities in the Outer Banks to support the transfer of knowledge (for example, how to set up a central disaster response station, communicate risk to tourists, and navigate the insurance process) from communities that have more experience and already have systems in place to deal with these coastal hazards. Regional tourism organizations such as North Carolina Coast Host can help connect tourism leaders from across coastal communities to support this knowledge transfer.

-

Identify and document all perceived risks (such as sea level rise and more frequent, severe hurricanes and storms) and the impact these risks can have on the tourism industry (for example, tourists not being able to reach the community due to a breach in NC Highway 12). In addition, community leaders should facilitate conversation about these risks to increase risk awareness among all tourism stakeholders. Local destination marketing and management organizations and regional tourism organizations (such as North Carolina Coast Host) can inform local and state level emergency managers of these risks.

Acknowledgments

The research reported here was funded by National Science Foundation award number 2002620 (RAPID: Disaster Recovery Decision Making in Remote Tourism-Dependent Communities). We greatly appreciate the time and insight shared by publication reviewers Lindsay Usher (The Cadmus Group), Cayla Cothron (North Carolina Sea Grant), and Helena Stevens (Ocracoke Tourism Development Authority).

References

Albright, E. A., and D. A. Crow. 2021. “Capacity Building Toward Resilience: How Communities Recover, Learn, and Change in the Aftermath of Extreme Events.” Policy Studies Journal 49 (1): 89–122. ↲

Berke, P., and G. Smith. 2009. Hazard Mitigation, Planning, and Disaster Resiliency: Challenges and Strategic Choices for the 21st Century. IOS Press. ↲

Bogardi, J. J., and A. Fekete. 2018. “Disaster-Related Resilience as Ability and Process: A Concept Guiding the Analysis of Response Behavior Before, During and After Extreme Events.” American Journal of Climate Change 7 (1): 54–78. ↲

Bonaiuto, M., G. Carrus, H. Martorella, and M. Bonnes. 2002. “Local Identity Processes and Environmental Attitudes in Land Use Changes: The Case of Natural Protected Areas.” Journal of Economic Psychology 23 (5): 631–653. ↲

Burley, D., P. Jenkins, S. Laska, and T. Davis. 2007. “Place Attachment and Environmental Change in Coastal Louisiana.” Organization & Environment 20 (3): 347–366. ↲

Covello, V. T. 2003. “Best Practices in Public Health Risk and Crisis Communication.” Journal of Health Communication 8: 5–8. ↲

Cox, R. S., and K. M. E. Perry. 2011. “Like a Fish Out of Water: Reconsidering Disaster Recovery and the Role of Place and Social Capital in Community Disaster Resilience.” American Journal of Community Psychology 48: 395–411. ↲

Cutter, S. L., L. Barnes, M. Berry, C. Burton, E. Evans, E. Tate, et al. 2008. “A Place-Based Model for Understanding Community Resilience to Natural Disasters.” Global Environmental Change 18 (4): 598–606. ↲

Finn, Alyson. 2019. “The Power of Preparedness.” NOAA Office of Response and Restoration Blog, September 22. ↲

Glavovic, B., M. Kelly, R. Kay, and A. Travers. 2015. Climate Change and the Coast: Building Resilient Communities. CRC Press. ↲

Hawkins, R. L., and K. Maurer. 2010. “Bonding, Bridging and Linking: How Social Capital Operated in New Orleans Following Hurricane Katrina.” The British Journal of Social Work 40 (6): 1777–1793. ↲

Hernández, Bernardo, M. Carmen Hidalgo, and Cristina Ruiz. 2020. "Theoretical and Methodological Aspects of Research on Place Attachment." In Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications, edited by Lynne Manzo and Patrick Devine-Wright. Routledge. ↲

Outer Banks Visitors Bureau. n.d. Statistics. ↲

Seekamp, E. L., M. Jurjonas, and K. Bitsura-Meszaros. 2023. Coastal Hazards and Tourism: Exploring Outer Banks Visitors’ Responses to Storm-Related Impacts. NC State Extension. ↲

Townshend, I., O. Awosoga, J. Kulig, and H. Fan. 2015. “Social Cohesion and Resilience Across Communities That Have Experienced a Disaster.” Natural Hazards 76: 913–938. ↲

United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. 2013. Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. ↲

U.S. Department of Homeland Security. 2016. National Disaster Recovery Framework. 2nd Edition. Washington, DC: Homeland Security. ↲

Visit North Carolina. 2023 County Level Visitor Expenditures. ↲

WRAL. 2019. “Dispatches from Dorian Coverage: Ocracoke Flooded, Hatteras Battered, but Other Coastal Areas Returning to Normal.” WRAL News Online, September 6. ↲

Publication date: Feb. 14, 2025

AG-973

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.