Overview

This publication provides definitions of two models for contemporary Extension work: (a) the Program Planning and Evaluation Model and (b) the Reactive Programming Model. The intent of the models is to provide guideposts and a common language for Extension education. These models, and this expository publication, are not meant to be prescriptive but to foster an understanding of the very complex nature of extending university knowledge and resources to North Carolina residents. The models inform the work of NC State Extension and help us to be more effective and efficient in achieving varied education goals. Extension models show “how the program is structured and organized” at the local level to achieve the “set of objectives” (Seevers and Graham 2012, 239).

The two models provide a straightforward, comprehensive approach to both proactive and reactive programming. The proactive programming described here reflects best practices and research related to program planning and evaluation. Extension models have traditionally focused only on proactive programming. While proactive programming is a necessary ongoing strategy for educating people and communities, reactive programming is required in time-sensitive situations. Reactive programming is necessary when communities face unexpected opportunities (for example, new public or private sector investments) and immediate challenges (such as a natural disaster). A reactive programming model emphasizes that Extension addresses questions, concerns, and motivations from the public with relevant, localized education.

The two models may contribute to the following multiple, varied goals:

- providing an archetype for planning and describing our programs

- streamlining our work

- planning programs for local, multicounty, district, state, and multistate levels

- linking program planning to evaluation

- coordinating university resources

- reporting impacts

- improving staff performance

- understanding performance appraisal

- understanding and improving Extension professionals’ competencies

- onboarding new Extension professionals and paraprofessionals

- engaging advisory groups

- explaining the science of Extension processes to elected officials

- acquiring stakeholder input

- improving accountability and evaluation

In sum, the models (a) improve Extension education science, (b) generate understanding of program development and evaluation, (c) build the capacity of Extension professionals and volunteers, and (d) contribute to impactful, sustainable Extension programs in every North Carolina community. This publication summarizes the research and best practices for quality Extension programs.

Program Planning and Evaluation Model

Introduction

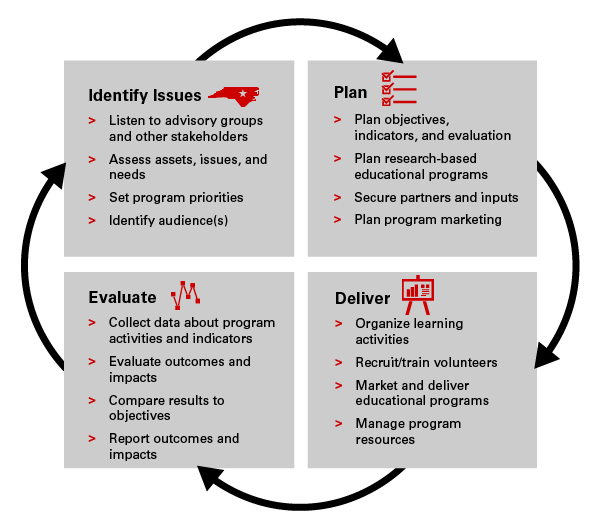

The NC State Extension Program Planning and Evaluation Model provides a standard for excellence in proactive educational programming. The model includes four dimensions, each containing a set of action steps (Figure 1).

- We identify issues that impact our local communities.

- We plan programs to address those challenges.

- We deliver research-based educational programs in local communities.

- We evaluate those programs to characterize any benefits to the environment, quality of life, and economy.

It is important to understand the NC State Extension Program Planning and Evaluation Model in terms of context and relationship to other such models. Numerous models delineate a coordinated process for planning, conducting, and evaluating Extension programs, including: The Logic Model (Taylor-Powell and Henert 2008); the Targeting Outcomes of Program (TOP) Model (Rockwell and Bennett 2004; Wholey et al. 2004); the Cornell Cooperative Extension Program Development Model (Duttweiler 2001); the Extension Education Learning System (Richardson 1994); the Tennessee Extension Program Planning and Evaluation Model (Donaldson 2008); the Communication Model (Brown and Kiernan 1998); and the Conceptual Schema for Programming in the Cooperative Extension Service (Boone et al. 1971). These models have contributed to a four-step model for NC State Extension.

Identify Issues

What are the assets, issues, and needs of the people you serve? To answer this question, first and foremost, listen to people. Observe the assets and needs in their lives. Examine Census data. Examine other data sources such as the local newspaper or chamber of commerce. The process of examining sources, making observations, and listening to people may be known as situational analysis, asset mapping, environmental scanning, or needs assessment. This publication will refer to the formal process of identifying issues as situational analysis.

Listen to Advisory Groups and Other Stakeholders

One of the most effective ways to conduct a situational analysis and plan programs to address assets, issues, and needs is to work with an advisory group (University of Wisconsin Extension 2003; Barnett et al 1999). Advisory groups should be representative of the geographic, political, racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity of the county or area served. Involving nontraditional or underserved clientele is crucial. Advisory groups typically have representation from community coalitions, government agencies, schools, and other important local institutions. Building relationships is paramount to effective advisory groups, community engagement, volunteer recruitment and management, and marketing and delivery of educational programs. Effective personal contact is the cornerstone of effective Extension programs (Black et al. 1992; Hagarty and Evans 1994).

The Advisory Leadership System for N.C. Cooperative Extension consists of county, district, and state advisory councils. The county membership may include 12 to 24 volunteers. Goals for the county advisory council include

- conducting needs assessments;

- marketing, resource development, and public advocacy;

- conducting major Extension programs; and

- sharing Extension success stories with elected officials and others.

Often, the advisory councils and Extension professionals consider the perceptions and ideas of other stakeholders in identifying community challenges. Examples might include incorporating the ideas of local elected officials or previous Extension program participants.

Extension agents form advisory groups so that residents are involved in shaping programs that address the community’s greatest needs and issues and build on its assets. Engage the advisory group in planning programs. Probe to discover more of the group’s insights into the community—its people and their problems. Research-based information on Extension advisory groups is sparse (Barnett et al. 1999), yet staff experiences in building and maintaining advisory groups have been described. University of Wisconsin Extension (2003) determined that advisory groups were most effective and active when they included

- members who were first invited in person or by telephone and then sent a letter to remind them of the first meeting;

- a rotating membership so that no one serves indefinitely and new ideas and perspectives are prevalent;

- members who feel free to discuss their community;

- members who feel their input is taken seriously; and

- members who are informed about program accomplishments.

Extension professionals should master techniques for engaging an advisory group, such as nominal group technique (NGT). NGT, a form of structured interactions (Averch 2004), was one of the first group methods that Extension professionals used for situational analysis (Garst and McCawley 2015). NGT can work well for a situational analysis in the context of any group meeting, including community forums and advisory committee meetings. Sample (1984) outlined the following steps for effective NGT:

- NGT Setup. NGT works best in groups of five to seven people. If the group is larger, divide into groups of five to seven. If possible, seat these people around a table or flip chart/screen to show their ideas.

- NGT Question. Ask an open-ended question such as: “What are some ways we could encourage consumers to buy local food?”

- Phase One (the “silent” phase). Explain that the first phase is to ponder possible solutions. Give people one or two minutes to think about their ideas and write them down. Let groups know how long they will work silently. One or two minutes should suffice.

- Phase Two. Begin by emphasizing that no judgment is allowed in this exercise. Ask each individual in the group to share one idea. As the person shares the idea, record it electronically or on a flip chart. Make sure everyone can easily view the ideas. You may allow people to ask for clarification, usually after all ideas have been listed.

- Phase Three. Ask each person to silently evaluate the ideas and vote individually for the best ones. If using a flip chart, you can tally votes with dots. Each person receives three dots (or votes) to place beside the best ideas.

- Phase Four. Show the group’s voting results and lead a discussion on the major ideas presented.

For a single group meeting or event, you might consider multiple rounds with a different question in each round. Additional rounds could continue to explore the local food topic, with sample questions including:

- “What would encourage more farmers to produce fruits and vegetables?”

- “What are the key ways to reach consumers about local food?”

- “What are the major barriers to purchasing local food?”

Though NGT is valuable, Extension professionals must strike a balance between sharing needs-assessment data with advisory groups and listening to their motivations, goals, and issues.

Assess Assets, Issues, and Needs

Issues and needs are often obvious. For example, a neighborhood with three home fires in one month is experiencing a conspicuous crisis. The situation provides the basis for a teachable moment on fire prevention and home safety. Taking advantage of such teachable moments can speed adoption of recommended safety and fire prevention practices. Some issues, on the other hand, may escape the notice of a casual observer. An example is the personal bankruptcy rate in a community. Debt is a problem that people may not be willing to make public. Affected people do not usually stand up in public meetings and say, “I have a problem managing my money and I need help.”

Below are links to some data indicators that could help you identify assets, issues, and needs in your community:

- NC State Extension County Data Profile

- United States Census Bureau

- The Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Kids Count Data Center

- North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services, Agricultural Statistics—Summary of Commodities by County

- North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, Reports and Statistics

- North Carolina Department of Commerce, Demand Driven Data Delivery System

Set Program Priorities

Extension will most likely not address every issue identified. Extension professionals engage with their advisory group to separate needs from wants and to prioritize the needs of greatest concern. Help your group to distinguish between cause and effect; for example, an increased public interest in vegetable gardening may be caused by an economic downturn. After your advisory group has identified the greatest needs, determine which needs are most likely to be served effectively through an Extension education program. The ultimate outcome of an Extension program may be systems changes, policy changes, or environmental changes (such as increasing healthy food choices in a school cafeteria). Extension works to bring about such changes through education.

Inform your advisory group of existing resources, for example, specific programs and the number of volunteers involved or Extension professionals with special certifications. Yet, be willing to introduce new programs if needed. What about the needs that cannot be addressed through education? Other public service agencies, clubs, and groups may be able to meet some or all of those needs. Educate advisory groups about the needs that Extension is most capable of addressing.

Identify Audience(s)

Identify the audience(s) to be served. Who is most affected by the issue? Who would benefit the most from education? Who is most at risk for the problem? For whom is the need greatest? Advisory groups are often helpful in identifying audiences.

Plan

Plan Outcomes, Educational Objectives, and Evaluation Techniques

Extension programs are designed to change practices and ultimately enhance quality of life by improving social, economic, or environmental conditions (SEEC). As an educator and change agent, you must plan the outcomes, establish the educational objectives, and choose the techniques for evaluating those outcomes.

Plan Outcomes: What is the desired result of your program? For example, if you are sponsoring a river rescue program in which volunteers collect litter along riverbanks, what is the ultimate goal you wish to achieve? To host a day for litter collection? Such an activity may represent only one step toward your ultimate goal. What needs are you trying to meet? How do you envision that households, families, and the community will be changed after the needs are met? Your ultimate goal might include one or more of these aims: to preserve clean water, to build a healthy natural environment, to improve human health, or to sustain tourism.

There are three types of planned outcomes for a program: short-term, intermediate, and long-term. A long-term outcome, also known as a condition or impact, is the ultimate result you hope to achieve. Short-term outcomes, also known as learning outcomes, are changes in knowledge, attitudes, skills, or aspirations (KASA). Intermediate outcomes, also known as action outcomes, are changes in actions or behaviors. Example 1 provides examples of planned outcomes for a parenting education program.

Example 1. Planned Outcomes for a Parenting Education Program

Issue: Parenting education

Learning Outcome:

- Parents increase knowledge of child development.

- Parents learn new ways to discipline.

- Parents become aware of community resources that will help them.

Action Outcome

- Parents practice improved parenting skills.

- Parents use a local parenting resource center.

Conditions

-

Rates of child abuse and neglect are reduced.

Plan Educational Objectives: Educational objectives are specific desired accomplishments. Educational objectives specify who will have achieved what from the program. These objectives should be attainable and realistic. Example 2 provides an example of a program for dairy farmers and its educational objectives and outcome indicators.

Example 2. Educational Objectives and Outcomes for a Potential Program Aimed at Dairy Farmers

Educational Objective: Dairy farmers will understand how following written plans for treating sick cows can keep antibiotic residue out of milk and increase income.

Planned Outcome: Dairy farmers will increase their farm income by at least 10 percent through higher milk quality.

Outcome Indicators:

- Number of dairy farmers who adopted written plans for treating sick cows

- Number of dairy farmers who increased income

Plan Evaluation: Extension’s goal is to measure program performance at the highest level. Changes must be tangibly measurable, so program leaders must plan how they will determine whether a change has occurred. Measurements of program performance are known as indicators. You must choose the evaluation technique you think will provide the most insight. Consider what kinds of data you need to collect to verify that your program achieved its objectives. You may need to use a survey, questionnaire, or pre-post test, or make personal observations (for example, weigh a harvested crop, count acres planted, or count yield data). Extension specialists are especially helpful to Extension agents in program evaluation; they may have or be able to identify validated evaluation tools and resources.

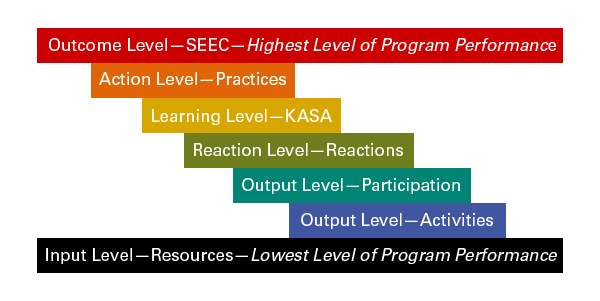

If change cannot be measured at the learning level (KASA), action level (change in practices), or outcome level (SEEC), that particular program is a lower priority than programs that do improve SEEC. Figure 2 describes the levels of program performance.

Plan Research-Based Educational Programs

Seldom does one educator have all the necessary facts and materials to conduct a research-based program. You might acquire information from Extension or external publications, research articles, curriculum packages, subject matter experts, or other vetted sources. When you identify curricula to address the program priorities, consult Extension specialists to confirm that the curricula are valid and aligned with current research.

Secure Partners and Inputs

Extension colleagues, advisory councils, and key stakeholders (for example, nonprofit organizations, government agencies, industry, and businesses) often partner to plan and conduct effective Extension programs. Forge partnerships to help you reach the selected audiences and achieve the planned objectives and indicators. Partners may be internal (for example, an Extension forage specialist) or external (for example, a local farm business that is providing funding). Partners may be involved in program planning, teaching, or funding.

Seek input from Extension agents and specialists, who regularly exchange valuable information about local assets, issues, and needs; Extension curricula; and relevant research.

The Plan of Action will reflect all of the program inputs (or investments), including your time and effort, and tangible resources such as Extension funding and a meeting location. Input is secured from collaborators or program partners. Share the Plan of Action with your supervisor for additional ideas and guidance about partners and inputs.

Plan Program Marketing

Marketing encompasses all of the activities conducted to plan, price, promote, and distribute products. In Extension education, the “products” are our educational programs (Kotler 1987). Effective Extension program marketing requires

- staying in contact with customers and stakeholders;

- understanding needs and expectations of customers and stakeholders;

- communicating the Extension mission; and

- publicizing our programs and how they benefit our customers and stakeholders.

Strategies that can be incorporated into a marketing plan include social media hashtags that are not copyrighted (Davis and Dishon 2017) and cross-program marketing. Cross-program marketing refers to marketing “Program A” to participants in “Program B,” such as marketing 4-H volunteer opportunities to NC State Extension Master GardenerSM volunteers. It has been suggested that cross-program marketing by Extension administrative assistants is especially effective, as they are often the first point of contact for Extension customers (Sneed et al. 2016).

Deliver

Organize Learning Activities

To organize the learning activities for an Extension program, consider the definition of a program and the broad categories of Extension teaching and learning activities. A program is a set of learning activities delivered to a specific audience with specific, measurable outcomes. A single activity does not constitute a program. Richardson et al. (1994) described Extension teaching and learning activities in four broad categories:

- Experiential. Learning that is based primarily on experiences. Experience becomes knowledge (Kolb 2015).

- Integrative. A teaching and learning technique that supports integrating new and previous knowledge and competencies.

- Reinforcement. Reminding learners of new knowledge and encouraging adoption of practices and innovations.

- Other. Teaching and learning methods that may fit in multiple categories.

Example 3 provides some examples of teaching and learning activities in broad categories. Select different activities from the broad categories to increase learning effectiveness.

| Experiential | Integrative | Reinforcement | Other Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Method demonstration | Conference | Fact sheet | Mass media |

| Result demonstration | Seminar | Reference notebook | Photograph |

| On-farm test | Panel | Publication | Bulletin board |

| In-home test | Meeting | Poster | Show |

| Tour | Discussion group | Personal letter | Fair |

| Field day | Phone conversation | Newsletter | Exhibit |

| Workshop | Personal visit | Social media | |

| Game | Office visit | ||

| Skit | |||

| Case study | |||

| Role-play | |||

| Food tasting |

Recruit/Train Volunteers

Almost all successful Extension programs require recruiting and training volunteers. Even the smartest, most resourceful volunteers benefit from training before they do something for the first time. The effective Extension professional is an effective manager of volunteers. For information on recruiting and training volunteers, Extension employees should refer to the NC State Extension Intranet.

Market and Deliver Educational Programs

The next action step in the Program Planning and Evaluation Model is to market and deliver the educational programs that have been identified and planned. These two steps, marketing and delivering, are interconnected, as Extension programs that address local needs are the products that we (in Extension) are marketing. Marketing does not mean the creation and deployment of a new brand to represent the program. Program marketing must always be conducted under the umbrella of organizational branding so that the entire community will receive consistent graphic and narrative messages. For example, an educational program does not require a new logo, color palette, or typography. Developing these or other new brand attributes would have the effect of separating the program from the university and the Extension organization. On the other hand, using the existing university and Extension branding resources would market the program as one part of our entire educational portfolio for North Carolina communities. One of the major benefits of branding is that audiences recognize and comprehend our work at a heightened pace (Caffarella and Daffron 2013).

In terms of program delivery, while considerable time and effort may have been expended to select curricula and teaching and learning activities, Extension professionals must be sensitive to the audience being served. It often takes time to build trust with new audiences so that they fully engage in an educational program. The program delivery must be somewhat fluid. For example, the program may need to be adapted to address specific audience needs. If Extension professionals discover that the audience has difficulty reading the printed material, they may need to employ nonprint methods.

Manage Program Resources

Managing resources—including volunteers and physical resources such as publications and equipment—is a big job that requires a multitude of skills. Cooper and Graham (2001) identified these necessary competencies:

- program planning, implementation, and evaluation

- customer service and working with people

- personal and professional development

- faculty and staff relations

- interpersonal skills

- management responsibility

- work habits

Extension provides a number of opportunities for its professionals to develop the necessary competencies for managing program resources. Examples include Extension professional associations, in-service training, and coaching from supervisors.

Evaluate

Collect Data about Program Activities and Indicators

During the course of a program, Extension professionals collect data, such as the number of people served by gender, race, and ethnicity. Extension professionals also collect indicator data, which may be as simple as counting a show of hands or as complex as evaluating questionnaires. Focus groups or interviews may also be used to assess the program’s impact.

Collecting data about an ongoing program is part of formative evaluation—the process of evaluating the performance of a program while it is happening (Wholey et al. 2004). Using formative evaluation data helps you to rework plans and adjust the program for maximum outcomes and impacts.

Keep in mind that the data you collect must be stored and retrievable. You might use statistical software programs, spreadsheets, or software research suites for this task.

Evaluate Outcomes and Impacts

Evaluation is essential to a learning organization because the knowledge gained helps us to work in new ways and achieve professional and organizational effectiveness (Rennekamp and Arnold 2009). Refer to the plan you devised, and remember to concentrate your evaluation efforts on learning outcomes, action outcomes, and conditions (impacts). For more information on evaluating outcomes and impacts, refer to the NC State Extension Intranet.

Compare Results to Objectives

Extension professionals compare results to objectives to gauge the performance of their program and to understand factors that affected performance. When comparing and contrasting impacts and objectives, ask yourself: (a) Were the objectives realistic? (b) How could program planning, performance, and evaluation be improved?

When comparing objectives to impacts, we often note mitigating factors or barriers to our plans. For example, an Extension pest management program may have been conducted precisely as planned but didn’t achieve its intended outcome because of a drought (barrier).

Report Outcomes and Impacts

Compose a professional program report, known in Extension as an “impact statement” (Example 4). It can be used to demonstrate accountability to the public, decision-makers, and funding partners, who want evidence of improvement in human or environmental capital. Impact statements should include

- the problem addressed;

- the number of people served;

- how indicators were measured, for example, a pre- or post-test;

- indicators of impact: the percentages, facts, and figures; and

- indicators that demonstrate practice change or improved SEEC.

Example 4. Impact Statement for a Student Financial Management Program

Of the 725 Example County students in the 4-H Financial Management Program, four classes were randomly selected and surveyed. Seventy-five students (10% of participants) completed the survey with a 100% response rate. The following impacts were achieved:

- 88% of students learned the different types of paycheck deductions.

- 75% learned how to write a check and keep a checkbook register.

- 74% learned the connection between education and their future career.

- 42% learned the importance of saving money.

Two months after attending a 4-H session on savings, one eighth-grader reported saving $50 and "buying Christmas presents for my family." The money was saved by not buying a daily soda at school. The youth was spending $25 per month in school vending machines. Eliminating those purchases saved more than $200 per year.

One-third (36%) of participants reported that they initiated conversation with their parents about money management as a result of this program.

Tips for effective impact statements

- In reporting outcomes and impacts, maintain the confidentiality and anonymity of program participants. For example, an appropriate impact statement would say: “A local farmer has doubled farm income through Extension’s value-added farm products program” rather than “Bill Jones made twice as much money this year through Extension’s value-added farm products program.”

- Providing a long list of activities rather than demonstrating actual impact is the major mistake made in impact statements. Evaluating activities, while important for improving programs, is one of the weakest measures of program performance.

- Impact statements should be distributed both internally and externally. For internal reporting, use the applicable Extension reporting system software. The data furnish information about our total Extension effort in North Carolina, which is reported to the United States Department of Agriculture and other stakeholders. Consider also reporting to other Extension personnel and specialists to build organizational knowledge about Extension programs.

- Outcomes should also be reported externally. Report outcomes to county advisory councils, elected officials, and other local stakeholders. Consider providing a “Report to the People” to provide an overview of Extension program results for the year and their major impacts.

Summary

The NC State Model for Extension Program Planning and Evaluation, which is based on research and best practices, helps integrate program planning with evaluation (Brown and Kiernan 1998). This model is used to meet goals that include

- effective program planning at the local, multicounty, district, state, and multistate levels;

- linking program planning to evaluation;

- coordinating university resources;

- reporting impacts;

- acquiring stakeholder input;

- improving accountability and evaluation; and

- satisfying legislative mandates.

Meeting these goals will result in an Extension program that yields substantial results for North Carolinians.

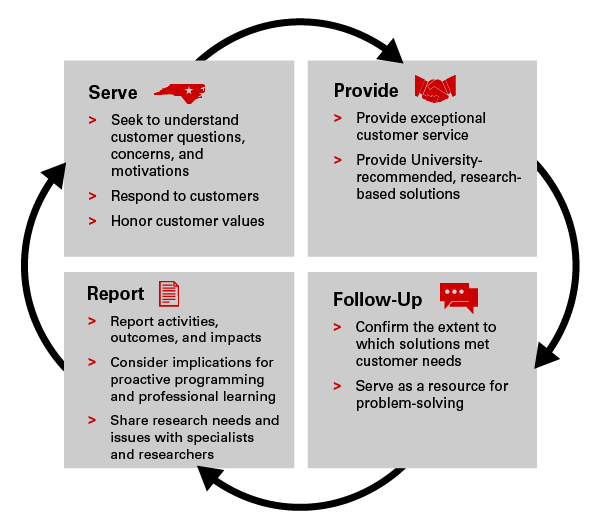

Extension Reactive Programming Model

Extension professionals are constantly reacting to North Carolinians’ questions, concerns, and motivations. In Extension, we refer to this as reactive programming. The NC State Extension Reactive Programming Model provides an overall roadmap for exemplary service (Figure 3). Please note that not every action step in the model is applicable to every situation.

- We serve North Carolinians by understanding and responding.

- We provide exceptional customer service focused on university-recommended, science-based solutions.

- We follow up with our customers and serve as an educational resource.

- We report our activities to provide accountability and to share knowledge.

In all of its efforts, Extension creates prosperity for North Carolina through community-based education. The Extension Reactive Programming Model has been informed by how farmers learn research (Franz et al. 2010a; Franz et al. 2010b; Piercy et al 2014); adult learning literature (Ambrose et al. 2010; Knowles et al. 2005); and nonformal education literature (Caffarella and Daffron 2013).

Acknowledgments

The text for Section 2 of this publication has been updated and adapted for North Carolina from Needs Assessment Guidebook for Extension Professionals by J.L. Donaldson and K.L. Franck (2016). See University of Tennessee Extension publication PB1839.

References

Ambrose, S.A., M.W. Bridges, M. DiPietro, M.C. Lovett, and M.K. Norman. 2010. How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Averch, H.A. 2004. “Using Expert Judgment.” In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation, edited by J.S. Wholey, H.P. Hatry, and K.E. Newcomer, 292–309. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Barnett, J., E. Johnson, and S. Verma. 1999. “Effectiveness of Extension Cotton Advisory Committees.” Journal of Extension 37, no. 6.

Boone, E.J., R.J. Dolan, and R.W. Shearon. 1971. Programming in the Cooperative Extension Service. North Carolina State University. Miscellaneous Extension Publication 72.

Brown, J.L. and N.E. Kiernan. 1998. “A Model for Integrating Program Development and Evaluation.” Journal of Extension 36, no. 3.

Black, D.C., G.W. Howe, D.L. Howell, and P. Becker. 1992. “Selecting Extension Advisory Councils.” Journal of Extension 30, no. 1.

Caffarella, R.S. and S.R. Daffron. 2013. Planning Programs for Adult Learners: A Practical Guide. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Cooper, A.W. and D.L. Graham. 2001. “Competencies Needed to Be Successful County Agents and County Supervisors.” Journal of Extension 39, no. 1 (February).

Davis, J. and K. Dishon. 2017. “Unique Approach to Creating and Implementing a Social Media Strategic Plan.” Journal of Extension 55, no. 4.

Donaldson, J.L. 2018. The Tennessee Extension Program Planning and Evaluation Model. University of Tennessee Extension publication W240.

Duttweiler, M. 2001. Cornell Cooperative Extension (CCE) Program Development Model.

Franz, N., F. Piercy, J. Donaldson, R. Richard, and J. Westbrook. 2010a. “How Producers Learn: Implications for Agricultural Educators.” Journal of Rural Social Sciences 25, no. 1: 37–59.

Franz, N.K., F.P. Piercy, J.L. Donaldson, R. Richard, and J.R. Westbrook. 2010b. “Farmer, Agent, and Specialist Perspectives on Preferences for Learning Among Today’s Farmers.” Journal of Extension 48, no. 3.

Garst, B. and P.F. McCawley. 2015. “Solving Problems, Ensuring Relevance, and Facilitating Change: The Evolution of Needs Assessment Within Cooperative Extension.” Journal of Human Sciences and Extension 3, no. 2: 26–47.

Hagarty, J. and D. Evans. 1994. “Effective Personal Contacts.” In Extension Handbook: Processes and Practices (2nd ed.), edited by D.J. Blackburn, 171–176. Toronto: Thompson Educational Publishing.

Kirkpatrick, D. 1996. “Great Ideas Revisited: Techniques for Evaluating Training Programs.” Training and Development 50: 54–59.

Knowles, M.S., E.F. Holton III, and R. Swanson. 2005. The Adult Learner (6th ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Kolb, D.A. 2015. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Kotler, P. 1987. “Strategies for Incorporating Marketing into Nonprofit Organizations.” In Strategic Marketing for Nonprofit Organizations: Cases and Readings, edited by P. Kotler, O.C. Ferrell, and C.W. Lamb, 3–13. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Piercy, F.P., N.K. Franz, J.L. Donaldson, and R. Richard. 2014. “Consistency and Change in Participatory Action Research: Reflections on a Focus Group Study About How Farmers Learn.” Journal of Qualitative Research 16, no. 3: 820–829.

Rennekamp, R.A. and M.E. Arnold. 2009. “What Progress, Program Evaluation? Reflections on a Quarter-Century of Extension Evaluation Practice.” Journal of Extension 47, no. 3.

Richardson, J.G., D.M. Jenkins, and R.G. Crickenberger. 1994. Extension Education Process and Practice: Program Delivery Methods. SD 6. Raleigh, NC: NC Cooperative Extension Service.

Richardson, J.G. 1994. Extension Education Process and Practice: Extension Education Learning System. SD 7. Raleigh, NC: NC Cooperative Extension Service.

Rockwell, Kay, and Claude Bennett. 2004. Targeting Outcomes of Programs (TOP): A Hierarchy for Targeting Outcomes and Evaluating Their Achievement. 48. Faculty Publications: Agricultural Leadership, Education and Communication Department. University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Taylor-Powell, E. and E. Henert. 2008. Developing a Logic model: Teaching and Training Guide. Madison: University of Wisconsin-Extension, Cooperative Extension, Program Development and Evaluation.

Sample, John A. 1984. “Nominal Group Technique: An Alternative to Brainstorming.” Journal of Extension 22, no. 2.

Seevers, B. and D. Graham. 2012. Education Through Cooperative Extension (3rd ed.). Fayetteville: University of Arkansas.

Sneed, C.T., A.H. Elizer, S. Hastings, and M. Barry. 2016. “Developing a Marketing Mind-Set: Training and Mentoring for County Extension Employees.” Journal of Extension 54, no. 4.

Varea-Hammond, S. 2004. “Guidebook for Extension Marketing.” Journal of Extension 42, no. 2.

University of Wisconsin Extension. 2003. Advisory Committees. Cooperative Extension Program Planning.

Wholey, J.S., H.P. Hatry, and K.E. Newcomer. 2004. Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons.

Publication date: Oct. 8, 2020

Reviewed/Revised: July 23, 2025

FCS-541

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.