Background

There can be no argument that the most famous aspect of honey bee biology is their method of recruitment, commonly known as the honey bee dance language. It has served as a model example of animal communication in biology courses at all levels and is one of the most fascinating behaviors that can be observed in nature.

The dance language is used by an individual worker to communicate at least two pieces of information to one or more other workers: the distance and direction to a specific location (usually a food source, such as a patch of flowers). The dance is most often used when an experienced forager returns to her colony with a load of food, either nectar or pollen. If the quality of the food is sufficiently high, she will often perform a “dance” on the surface of the wax comb to recruit new foragers to the resource. The dance language is also used to recruit scout bees to a new nest site during the process of reproductive fission, or swarming. Recruits follow the dancing bee to obtain the information it relays and then exit the hive to travel to the location of interest. The distance and direction information contained in the dance are representations of the source's location (see "Components of the Dance Language" section) and thus is the only known abstract “language” in nature other than human language.

The dance language is inextricably associated with Karl von Frisch, who is widely credited with interpreting its meaning. He and his students carefully described the different components of the language through decades of research. Their experiments typically used glass-walled observation hives. They trained marked foragers to food sources placed at known distances from a colony, then carefully measured the angle and duration of the dances when the foragers returned. The work eventually earned von Frisch the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1973.

The concept of a honey bee language, however, has not been free of skepticism.

Several scientists, including Adrian Wenner, have argued that the dance's existence does not necessarily mean that it communicates information about the location of a food source. Critics have argued that floral odors on a forager's body are the major cues that recruits use to locate novel food sources. Many experiments have directly tested this alternative hypothesis and demonstrated the importance of floral odors in food location. In fact, von Frisch held this same opinion before he changed his mind in favor of the abstract dance language.

The biological reality, however, is somewhere between these two extremes. The most commonly accepted view is that recruits go to the area depicted in the dance, but then “home in” to the flower patch using odor cues. Researchers have built a robotic honey bee that is able to perform the dance language and recruit novice foragers to specific locations. The robot, however, is unable to properly recruit foragers to a food source unless there is some odor cue on its surface.

Nevertheless, it is clear that honey bees use the distance and direction information communicated by the dance language, which represents one of the most intriguing examples of animal communication.

Components of the Dance Language

At its core, there are two elements communicated in a dance: distance and direction. These two pieces of information are translated into separate components of the dance.

Distance

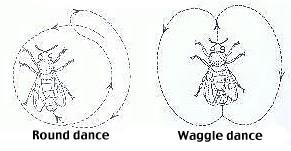

When a food source is very close to the hive (less than 50 meters away), a forager performs a round dance (Figure 2). She does so by running around in narrow circles, suddenly reversing direction to her original course. She may repeat the dance several times at the same location or move to another location to repeat the dance. After the round dance has ended, she often distributes food to the bees following her. A round dance, therefore, communicates distance (“close to the hive”), but no direction.

Food sources that are at intermediate distances (between 50 and 150 meters away) are recruited to with the sickle dance. The form of this dance is crescent-shaped, a transitional dance between a round dance and a waggle dance (which is in the form of a figure eight).

A waggle dance (Figure 2), also called a wag-tail dance, is performed by bees foraging at food sources that are more than 150 meters away from the hive. This dance, unlike the round and sickle dances, communicates both distance and direction to potential recruits. A bee that performs a waggle dance runs straight ahead for a short distance, returns in a semicircle to the starting point, runs again through the straight course, then makes a semicircle in the opposite direction to complete a full figure-eight circuit. While running the straight-line course of the dance, the bee’s body, especially the abdomen, wags vigorously sideways. This vibration of the body produces a tail-wagging motion. At the same time, the bee emits a train of buzzing sound, produced by wingbeats, at a low frequency of 250 to 300 hertz (cycles per second) with a pulse duration of about 20 milliseconds and a repetition of frequency of about 30 seconds.

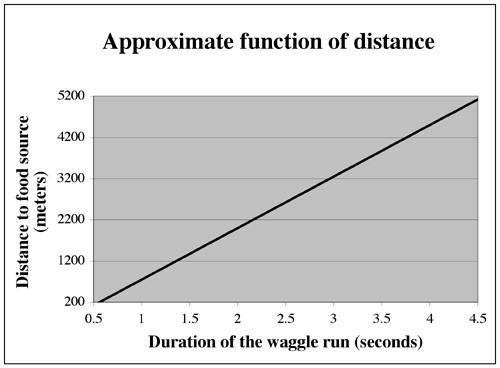

While several variables of the waggle dance are correlated with distance information (for example, dance “tempo” and duration of buzzing sounds), the duration of the straight-run portion of the dance, measured in seconds, is the simplest and most reliable indicator of distance. As the distance to the food source increases, the duration of the waggling portion of the dance (the “waggle run”) also increases. The relationship is roughly linear (Figure 3). For example, a forager that performs a waggle run that lasts 2.5 seconds is recruiting for a food source located about 2,625 meters away.

Direction

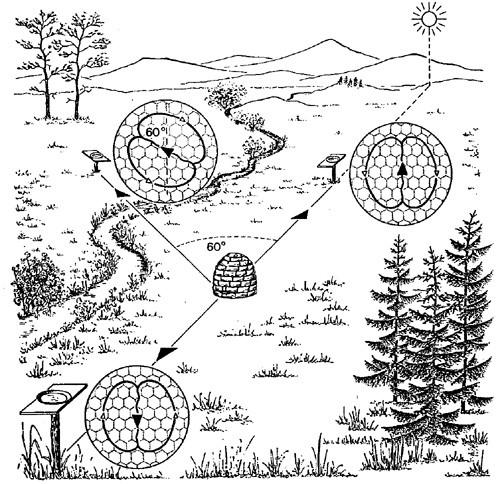

While the representation of distance in the waggle dance is relatively straightforward, the method of communicating direction is more complicated and abstract. The orientation of the dancing bee during the straight portion of her waggle dance indicates the location of the food source relative to the sun. The angle that the bee adopts, relative to vertical, represents the angle to the flowers relative to the direction of the sun outside of the hive. In other words, the dancing bee transposes the solar angle into the gravitational angle. Figure 4 shows three examples. A forager recruiting to a food source in the same direction as the sun will perform a dance with the waggle run portion directly upon the comb. Conversely, if the food source is located directly away from the sun, the straight run would be directed vertically down. If the food source is 60 degrees to the left of the sun, the waggle run would be 60 degrees to the left of vertical.

Because the direction information is relative to the sun's position, not the compass direction, a forager's dance for a particular resource will change over time. This is because the sun's position moves over the course of a day. For example, a food source located due east will have foragers dance approximately straight up in the morning (because the sun rises in the east), but will have foragers dance approximately straight down in the late afternoon (because the sun sets in the west). Thus, the time of day—or, more important, the location of the sun—is an important variable to interpret the direction information in the dance.

The sun's position is also a function of one's geographic location and the time of year. The sun will always move from east to west over the course of the day. However, above the Tropic of Cancer, the sun will always be in the south, whereas below the Tropic of Capricorn, the sun will always be in the north. Within the tropics, the sun can pass to the south or to the north, depending on the time of year.

In summary, to translate the direction information contained in the honey bee dance, one must know the angle of the waggle run (with respect to gravity) and the compass direction of the sun (which depends on location, date, and time of day).

Additional Resources

Barth, F. G. 1985. Insects and Flowers: The Biology of a Partnership. Princeton University Press.

Seeley, Thomas D. 1995. The Wisdom of the Hive: The Social Physiology of Honey Bee Colonies. Harvard University Press.

von Frisch, Karl. 1967. The Dance Language and Orientation of Bees. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

von Frisch, Karl. 1976. Bees: Their Vision, Chemical Senses, and Language. Revised Edition. Cornell University Press.

Wenner, Adrian M., and Patrick H. Wells. 1990. Anatomy of A Controversy: The Question of a “Language” Among Bees. Columbia University Press.

More Information

For more information on beekeeping, visit the NC State Extension Beekeeping Notes website

|

David R. Tarpy Professor and Extension Apiculturist Department of Applied Ecology, Campus Box 7617 North Carolina State University Raleigh, NC 27695-7617 TEL: (919) 515-1660 FAX: (919) 515-7746 EMAIL: david_tarpy@ncsu.edu |

Jennifer J. Keller Apiculture Technician Department of Applied Ecology, Campus Box 7617 North Carolina State University Raleigh, NC 27695-7617 TEL: (919) 513-3967 FAX: (919) 515-7746 EMAIL: jennifer_keller@ncsu.edu |

Publication date: Dec. 17, 2025

AG-646

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.