In beef cattle production, establishing a defined breeding season requires producers to remove the bulls from the cowherd for at least 30 days during the year. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 2017, approximately 41.3% of cow-calf operations had at least one defined breeding season, with the majority of these operations concentrating their breeding season from May to July after a spring calving calendar (USDA–APHIS–VS−CEAH–NAHMS 2021). Determining the period and the length of the defined breeding season relies solely on the producers who must consider their marketing options, feed availability, weather, labor, and personal preferences. The main goal of a defined breeding season is having calves born within a short period of time such as 45 to 90 days, although calving windows as long as 180 days are still observed in defined breeding seasons.

This publication was developed for beef producers, farm workers, and Extension agents who wish to transition from year-round breeding to a defined breeding season.

Why Should I Implement a Defined Breeding Season?

Establishing a defined breeding season helps producers increase the efficiency and profitability of their operation (Ramsey et al. 2005). For example, the nutritional management of the cowherd can be tailored according to physiological status (open, early pregnancy, or late pregnancy). This is important because the protein requirements are greater for suckled cows immediately after calving compared to non-suckled cows during their last trimester of gestation. In addition, there are other advantages of a defined breeding season:

-

Uniform calf crop: A short breeding season results in uniform-sized calves, which increases their marketability. At the same time, producers have the ability to increase the proportion of older, heavier calves at weaning when working on the calving distribution with synchronization protocols, which will increase the number of females pregnant at the beginning of the breeding season. Females that breed earlier will also calve earlier and have more time to recover for the following breeding season.

-

Concentrated labor: Calf management activities such as vaccination, castration, and weaning can be done on the same day for the entire calf crop.

-

Closely monitored calving: Cows and heifers in late gestation can be moved closer to the working facility so that calving can be monitored.

-

Enabling of culling decisions: Producers can conduct pregnancy diagnoses after the breeding season to cull open cows.

-

Adopting pre-breeding management strategies: Important management strategies such as pre-breeding vaccination of the cowherd, reproductive tract scoring of heifers, and breeding soundness examinations of bulls can be conducted at the appropriate time. These management strategies directly affect the pregnancy outcomes in cow-calf operations.

The adoption of a defined breeding season optimizes management practices in cow-calf operations and enables producers to plan activities accordingly. Management practices such as culling decisions influence profitability because open cows that remain in the herd will incur costs without generating revenue from producing calves. It is estimated that feeding costs will range from $450 to $1,200 per cow per year. Therefore, it is important that producers conduct a pregnancy diagnosis after the breeding season to cull open females, as well as females that are not desirable to stay in the herd. This includes cows with a bad disposition.

Despite these known benefits, it is common for producers to fear the transition from year-round to a defined breeding season. Fears include potential revenue loss from the decreased number of calves produced and greater culling rates caused by cows not falling in the defined breeding window. To avoid a detrimental economic impact on the operation, we suggest in this publication a phased transition created by Triplett in 1977 and established over the course of four years.

When Should I Start My Breeding Season, and How Long Should It Be?

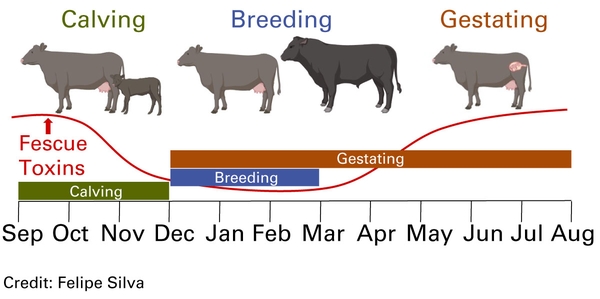

The final decision on the season and the length of the breeding season relies solely on the producer. The decision depends upon feed availability, weather patterns, marketing options, labor availability, and personal preferences. Thus, the breeding calendar varies among operations. Local characteristics can play an important role when planning for breeding. For example, fescue toxicosis is a major issue for producers located in the fescue belt in the southern states. This leads to decreased reproductive outcomes and producers who must follow a fall calving calendar to minimize issues.

Since fescue toxicosis is generally observed during the summer and fall, conducting the breeding season over the winter months can decrease the negative impact of fescue toxicosis on reproductive outcomes. For example, the scenario depicted in Figure 1 represents a 90-day breeding season beginning in December. By applying this management strategy, the breeding season overlaps with the period when there is a decreased concentration of toxins in the forage. This is beneficial because fescue toxicosis has been shown to impair the concentration of circulating reproductive hormones, ovarian function, calving rate, and milk production in beef cattle (Poole and Poole 2019). If the goal is to be close to a 12-month calving interval, then producers must keep their breeding season to 90 days or shorter.

How Do I Transition From Year-Round Breeding to a Defined Breeding Season?

The transition from year-round breeding to a defined breeding season must be done in phases to avoid aggressive culling, which leads to financial burdens. In general, cowherds in a year-round breeding season naturally concentrate calving in specific seasons or months. We suggest that producers include some of those months in the defined breeding season. We propose a four-year implementation strategy for transitioning to a 90-day breeding season (Table 1).

Year 1: Pull the bulls from the herd on June 30 and conduct a pregnancy diagnosis either by transrectal ultrasonography 30 days later or by rectal palpation 45 to 60 days later. At this stage, all open cows without calves and open cows with calves that are at or over five months of age should be culled. Bulls must be kept in a secure pen to avoid breaking into the cowherd paddocks during the off-season.

Year 2: Put the bulls in the herd from January 1 to June 30. Conduct a pregnancy diagnosis as done in year 1. At this point, all open cows should be culled.

Year 3: Put the bulls in the herd on February 1 until June 30. Conduct a pregnancy diagnosis and cull all open cows.

Year 4: Put the bulls in the herd from April 1 until June 30. Conduct a pregnancy diagnosis and cull all open cows.

Year 5+: Continue the same management strategy as Year 4. Beginning in Year 5, you will have a 90-day calving season with your herd.

Take Home Messages

-

Establishing a defined breeding season increases efficiency and profitability in beef operations.

-

Transitioning from year-round breeding to a 90-day breeding season can be implemented in four years, which will decrease aggressive culling.

-

Contact your N.C. Cooperative Extension area livestock agent for further assistance with planning and implementing a defined breeding season.

References

Literature cited

Poole, Rebecca K. and Daniel H. Poole. 2019. "Impact of Ergot Alkaloids on Female Reproduction in Domestic Livestock Species." Toxins 11, no. 6: 364. ↲

Ramsey, Ruslyn, Damona G. Doye, Clement E. Ward, James M. McGrann, Lawrence L. Falconer, and Stanley J. Bevers. 2005. "Factors Affecting Beef Cow-Herd Costs, Production, and Profits." Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics 37, no 1: 91-99. ↲

USDA–APHIS–VS−CEAH–NAHMS. 2020. Beef 2017: Beef Cow-Calf Management Practices in the United States. Fort Collins: USDA. ↲

Triplett, C. M. 1977. “A Controlled, Seasonal Cattle Breeding Program.” In Southern Regional Beef Cow-Calf Handbook. North Carolina Agricultural Extension Service. SR-1005. ↲

Publication date: June 3, 2024

AG-964

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.