Introduction

Many different species of stinging insects are often mistaken for honey bees, or casually referred to as “bees.” Being able to distinguish honey bees from wasp or other bee species is important to make appropriate decisions about potential control. The following is an overview of some non-honey bee stinging insects in North Carolina.

Generally, wasps tend to be more slender and with fewer hairs on the body than bees. Wasps also tend to feed on other insects, whereas bees tend to primarily feed on floral sources (pollen and nectar). There are social and solitary species in both groups.

Yellowjackets

Yellowjackets are small wasps with distinct yellow and black markings. They are very agile flyers, and they construct small tan nests made of paper, usually within a cavity or void. Common locations for nests are in lawns, particularly in sandy exposed areas, as well as at the bases of trees or shrubs. In wooded areas, they are common in rotted logs or stumps. Occasionally, yellowjackets will nest in attics or wall voids of houses or storage buildings. Cinder block openings are another common place they have been known to inhabit. Small holes leading to large covered cavities are ideal for yellowjacket nest sites.

Biology

An individual yellowjacket queen begins building a nest alone in the spring. She takes on this task by herself, but once she has produced enough workers to take over nest-building and foraging duties, she focuses on egg laying. The workers expand the nest, forage for food, and feed the young. They also guard and defend the nest. Like other predatory wasps, their diet consists mainly of other insects such as flies and bees. The insects continue to enlarge the nest until fall when there may be 600-800 yellowjacket workers. Frequently, it is not until this time that the nest is noticed, although it has been there for many weeks. In the late summer, the colony produces reproductives. The mated female reproductives will serve as the next generation of queens the following spring. The males cannot sting, due to lack of a stinger. Nests are abandoned by wintertime and the future queens seek shelter alone, in protected places under tree bark, in old stumps, or sometimes attics. The current year’s nests are not reused the following spring.

Behavior

Yellowjackets, in particular, may be late-season pests around picnics, trash cans, and humming bird feeders as they forage. The only way to control this situation is to locate and destroy the nest, which is rarely possible. As an alternative, keep all outdoor food and drinks covered, except while actually eating. Hummingbird feeders can be fitted with mechanical guards or a coating of petroleum based chest rub on where the insects land. It is also important not to spill sugar water when filling the hummingbird feeder. Trash cans should be kept covered or have a flap over the opening. Defensive behavior of yellowjackets occurs in response to nest defense. If the nest is not in the immediate vicinity, the likelihood of stings is greatly reduced.

Control

The first decision to make is whether control is actually necessary. In spite of their reputation, yellowjackets are actually beneficial because they prey on many insects that we consider to be pests. They also serve as food for bears, skunks, birds, and other insects. It is important to also note that these colonies die out each year. If a yellowjacket nest is built in a secluded area, you may choose to simply wait until the colony dies out in late fall or early winter. The nest will slowly deteriorate from weather or from attack by hungry birds. If a nest is located where people may be stung or if you (or others) are hypersensitive to wasp stings, then colony destruction may be appropriate. Control is best achieved by applying a pesticide directly into the nest opening. This can be done at anytime of the day, but near dusk, most of the wasps are more likely to be inside the nest. You can use any of the aerosol “Wasp & Hornet” sprays that propel insecticide in a stream about 10-12 feet. Direct the spray into the nest opening and then move away from the area in case any of the wasps emerge from the nest. You may need to be repeat the treatment on the following evening. Do not use a flashlight while spraying, as this will attract the angry wasps near you and will sting anyone nearby. Finally, do not pour gasoline down the hole of a nest. This is extremely dangerous, as it is a flammable hazard and does immense damage to the surrounding environment.

If the nest is in a wall void or other inaccessible area in your home, you may consider hiring a pest control operator to do the work for you. If the nest is in a wall, it may be desirable to remove it after spraying to avoid attracting carpet beetles that can subsequently invade the nest and eventually attack garments made wool, silk, or fur. Yellowjacket traps (commercial or otherwise) have not shown to be of any value in reducing a yellowjacket problem in the southeastern United States. In trash disposal or recycling areas, closed containers and the use of PDB (paradichlorobenzene) blocks may help repel some insects.

Paper Wasps

Paper wasps (Polistes sp.) are long-legged, reddish-brown to black insects with slender, spindle-shaped abdomens. They may have differing degrees of yellowish or brown striping, and they can vary in size. Paper wasps are commonly confused with muddauber wasps, which are dark blue or black metallic-colored wasps that build mud nests and are not prone to sting. Adult paper wasps typically prey on caterpillars and are considered quite beneficial. However, they will sting in defense of their nests.

Biology

In the spring, female reproductive paper wasps construct grey, papery honeycomb-like cells under eaves, overhangs, window sills, awnings, deck railings, or open barns. They are connected to the base by a single stalk (called the ‘petiole’). Once the first few cells have been constructed, the foundress will lay eggs which hatch within a few days. The female wasps will feed chewed-up caterpillars and other soft arthropods to their young larvae until they seal their cells and pupate. Once enough new female worker wasps have emerged, they take over the duties of food collection, nest construction, and defense, while the queens remain on the nests and produce more offspring. During the spring and summer, colonies continue to grow to 6-8 inches in diameter with several dozen wasps. Stinging may be more likely during this time.

Behavior

In the early fall, colonies begin to produce males and reproductive female wasps. These reproductive females, which constitute next year’s queens, mate with males and leave the nest in search of protected spots in which they spend the winter. Overwintering queens seek shelter in hollow trees, under bark, in wood piles, attics, chimneys, barns, under siding, or other similar cavities. The remaining worker wasps eventually die and the nests are abandoned. These old nests are not reused next year.

On any warm day during the cold season, the wasps may become more active. If they are resting in an attic, wall void, or crawlspace, the wasps may be attracted to light coming through a gap in the baseboard, a wall fixture, or around an AC vent and enter inside the building. Once inside a dwelling, the wasps may be found crawling on the floor and furniture, or they may be attracted to light shining through windows. Since there is no nest or young to defend, the only real danger of being stung is from accidentally stepping on or pressing against one. Homeowners sometimes become unnecessarily concerned when they observe numerous wasps beating against the windows on a warm winter day. This behavior is not fully understood, but poses no threat. Taller houses and upper stories seem to be more attractive. Crane and tower operators are often dismayed by the large numbers of wasps which may congregate around these structures when the temperature is favorable.

Control

It is important to remember that paper wasps are actually beneficial insects, since they prey on many garden pests (particularly caterpillars). However, if the wasp nests are considered to be a hazard, they can be destroyed in the evening with an aerosol insecticide that is labeled for “hornets or wasps.” As with any colony of stinging insect, it is important to conduct control at night and turn off any flashlight or light source that might be on during this time. The paper wasps may be attracted to the light and sting anyone nearby. Small nests, with only one or a few wasps, may be knocked down with a broom. In homes, attic vents should be properly screened to exclude overwintering queens. If they are already present, a total-release aerosol may be used on a warm day. Follow the product label instructions concerning how many cans are needed for the size area you are treating. Never exceed this number of units, and always be careful using these products near open flames, as they could ignite.

Wasps that enter a dwelling may be swatted, stepped on, or sucked up with a vacuum. They can also be carefully collected in a jar and released outside. Workers on towers or tall structures need to be extra vigilant for wasp nests. Work may need to be scheduled during cool temperatures. Workers should wear long sleeved shirts, long pants, gloves, and a hat. A beekeeper’s veil may be worn to protect the face and neck, as long as doing so does not pose a work hazard.

Carpenter Bees

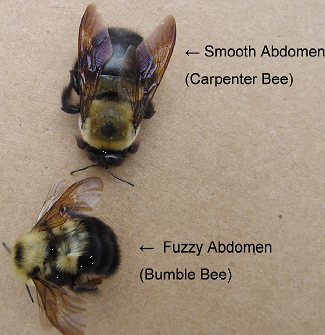

Carpenter bees are large, black and yellow bees commonly seen during the spring hovering around porch rails, decks, deck furniture, and underneath the eaves of houses. They can be distinguished from bumblebees in that the carpenter bee has a hairless black abdomen. The carpenter bee is so-called because of its habit of excavating tunnels in wood with its strong jaws. They leave a round, half-inch hole in wood boards. There is usually a pile of fresh sawdust and a yellow trail of waste on surfaces below the hole. Wooden decks, overhangs, and other exposed wood on houses are prime targets. Painted and treated woods are less preferred by carpenter bees, but they are still susceptible to attack.

Carpenter bees, like their distant relatives the carpenter ants, differ from termites in that they do not consume the wood as food. They simply excavate tunnels for nesting sites.

Biology

Carpenter bees overwinter as adults, often inside old nest tunnels. In North Carolina, they typically emerge in April and May. The males are usually first to appear. Males can be distinguished from females by a whitish spot on the front of the face. The males do not have stingers, but they are extremely territorial and will harass any insect or human that comes into the area. Females can sting, but rarely do so unless confined in your hand or are highly agitated. Newly emerged females feed on plant nectar then begin constructing new tunnels after a few weeks. The entrance holes start upward (or inward) for about one-half inch or more, then turn horizontally and follow the wood grain. The larval galleries typically run six to seven inches, but may exceed one foot in length. Occasionally, several bees use the same entrance hole, but they have individual galleries branching off of the main tunnel. If the same entrance hole is used for several years, tunnels may extend several feet in the wood. Inside her gallery, a female bee gradually builds a large pollen ball that serves as food for her offspring. She deposits an egg near this pollen ball and then seals off the section of tunnel with chewed wood. The female constructs additional cells in this manner until the tunnel is completely filled, usually with six to seven cells (depending on length of the tunnel). The adult bees die in a matter of weeks, but the eggs hatch in a few days and the offspring complete their development in about 5 to 7 weeks. Adults begin to emerge later in the summer. Although the bees remain active by feeding on pollen in the area of their nest, they do not construct new tunnels. Some may be seen cleaning out old tunnels which they will use as overwintering sites when the weather turns cold.

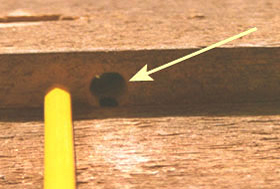

Damage

Typically, carpenter bees do not cause serious structural damage to wood unless large numbers of bees are allowed to drill many tunnels over successive years. Old barns may be particularly susceptible to carpenter bee damage over a course of many years. The bees often eliminate their wastes before entering the tunnel. Yellowish-brown staining from voided fecal matter may be visible on the wood beneath the hole. It can be a chore to clean this waste material off of glass or car paint. Woodpeckers may damage infested wood in search of bee larvae in the tunnels. In the case of thin wood, such as siding, this damage can be severe. Holes on exposed surfaces may lead to damage by wood-decaying fungi or attack by other insects, such as carpenter ants.

Control

Preventing carpenter bee damage is difficult (or nearly impossible) for several reasons. First, protective insecticide sprays applied to wood surfaces are effective for only a short period, even when repeated every few weeks. Since the bees are not actually eating the wood and they are active over several weeks, they are rarely exposed to lethal doses of the pesticide. Second, since virtually any exposed wood on the house could be attacked, it is difficult and usually impractical to try applying a pesticide to all possible sites where the bees might tunnel. Trying to spray bees that are seen hovering about is not a sensible (or particularly safe) use of pesticides either. Swatting hovering bees will often prove to be just as effective.

Treating each individual nest hole can be very time consuming, but can reduce further nesting activity. Products containing carbaryl (Sevin®), cyfluthrin, or resmethrin are suitable for carpenter bee control. A list of chemicals for use against carpenter bees can be found in the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual. Avoid inhaling the insecticide or contaminating your clothing with the spray. Always stand upwind from the surface you’re treating. Treated tunnels should be sealed with a small ball of aluminum foil and caulked after 24-36 hours. Since active or abandoned tunnels may be used as overwintering sites, or they can be re-used next spring for nesting, it is important that they be sealed permanently. Depending on the particular situation, treatment may be best performed at night, as the female will guard the nest and sting anyone that poses an immediate threat. The insecticide treatment is important because it kills both the adult bee as well as any offspring as they attempt to emerge later. Simply plugging untreated tunnels with wire mesh or similar material might trap bees inside, but more resourceful bees will simply chew another exit hole.

Bumble Bees

Bumble bees are social insects that live in small colonies in the ground. Some of the more common bumble bees encountered around the home and garden are the common Eastern bumblebee Bombus impatiens, the American bumble bee Bombus pennsylvanicus, and the Prairie bumble bee Bombus griseocollis.

Biology

Bumble bees are large-bodied bees with horizontal black and yellow stripes running across the abdomen. They have longer faces and a more pronounced proboscis than carpenter bees. The bumble bee has a hairy abdomen, as apposed to the carpenter bee, which has a shiny abdomen. They are not very fast fliers, and they can be clumsy around flowers. The different species in North Carolina varying in size. The queen is usually larger than most of the other bees in the colony. Males have no stinger and have a rounded abdomen. Bumble bees nest in colonies that can contain up to 200 or more individuals, and they are very important pollinators of both crops and wildflowers.

The bumble bee colony is made up of three types of individuals: the queen, female workers, and males. The reproductive females are the only bees from the nest that overwinter. They can be seen in the spring feeding on flowers and looking for new places to start a colony. Bumble bees prefer abandoned animal holes in the ground, but they have also been known to nest in rotten tree cavities, stump holes, used bird houses, and some human structures where there is soft nesting material present. Nectar is collected and stored in one or two small sac-like “honey pots” built from wax and pollen. The workers enlarge the nest and, by midsummer, the colony will have 20 to 100 workers. The colony produces reproductives (new queens and males) in the late summer, when they leave the nest to take mating flights. The successfully mated queens fly to the ground and hibernate 2 to 5 inches deep in the soil or logs. The production of reproductives signals the end of the colony’s life. The overwintering queens emerge the next spring to complete their life cycle.

Control

Bumblebees are a very important insect species, so control should only be done if it is absolutely necessary for personal protection. Locate the nest during the day when the bees are active, then come back at night and apply an aerosol pesticide designed for wasps and hornets. Like many other colonies of stinging insects, care should be taken to turn off any hand-held light sources before applying pesticides.

Cicada Killer

Cicada killers (Sphecius speciosus) are members of the wasp genus Sphecius, which is composed of 21 species world wide. These insects are closely related to ants, bees, and other Hymenoptera. The cicada killer draws the attention of many people due to its large size and habitat preference, such as yards and lawns. The cicada killer is a large black and yellow wasp, ranging from 11⁄8 to 15⁄8 inches long. They have small yellow markings on the thorax, plus six yellow markings on their large abdomen, three on each side. Their heads and wings are a reddish color.

Biology

The cicada killer is a solitary wasp species, unlike paper wasps and yellow jackets. The cicada killer pupates and overwinters underground in tunnels excavated by the parents the previous summer. In North Carolina, they normally hatch out between June and July. The males emerge earlier than the females, and mating occurs after the females have hatched. The females usually mate with more than one male. They mate in designated mating areas where the males congregate, known as leks. After mating, the female cicada killer begins searching for an area to dig her burrows. These areas are usually near the edges of woods where they can readily find cicadas, their food source. The soil cannot be very moist and must be well drained. Because of this habitat preference, it is not uncommon for cicada killers to inhabit grassy lawns around human habitats. The female, after choosing the nest site, begins to dig a burrow usually are not much deeper than a foot that can reach up to three feet long.

A female cicada killer hunts adult cicadas, large plant-feeding insects that create loud, familiar sounds in the summer. She grabs her prey and paralyzes it, dragging or slowly carrying the cicada back to the entrance of her nest. She then will lay an egg on the second leg of the paralyzed cicada. The cicada does not die right away; rather, it is eaten alive by the developing wasp larva. The cicada remains alive so that the insides do not spoil. The larva hatches, eats the cicada, and then pupates over winter, finally emerging the following summer. The adult wasps feed on sap and nectar.

It is not uncommon for the female cicada killer to drop the cicada that she is carrying, due to weight and distance. One may occasionally find a paralyzed (but not parasitized) cicada on the ground, unable to move yet still alive. Most of the time these paralyzed insects are eaten by ants and birds.

Control

If you have cicada killers in your lawn, chances are that they will be there year after year. Cicada killers choose lawns due to the various conditions that are presented. They enjoy southern facing hills with well drained soil. Adequate fertilizer and liming of the soil, combined with consistent watering, can render your lawn uninhabitable for this species.

European Hornet

The first reported specimen of Vespa crabro was reported around 1840 in the state of New York. Since that time, it has worked its way south along the east coast and has spread throughout the eastern United states. Other names for V. crabro include the brown hornet or the giant hornet. The European hornet is often mistakenly called the Japanese hornet, but in fact the Japanese hornet is not found in the United States but rather is restricted to the mountains of Japan and Asia. The European hornet is the largest true hornet found in the United States.

Note that this species is completely different from two relatively new invasive hornets—the Asian Giant hornet (also known as the "murder" hornet) and the Yellow-legged hornet—neither of which are in North Carolina. For more information, see the side by side picture comparison of different wasp species.

Description

Adults resemble yellow jackets, but are much larger (about 11⁄2 in.) and are brownish red with a dull yellow abdomen. Queens, which may be seen in the spring, have more red than brown, and are larger than the workers. Nests are typically built in hollow trees, but they are often found in barns, sheds, attics, and wall voids of houses. They are usually not noticed until the colony has reached a large size. This can present a problem to the human inhabitants due to the defensive nature of V. crabro. Unlike its cousin, the bald-faced hornet, European hornets rarely build nests that are free hanging or in unprotected areas. Frequently, the nest is built at the cavity opening, rather than deep within. The outside of the exposed nest will be covered with coarse, thick, tan, paper-like material fashioned from decayed wood fibers. The hornet mashes it up with its mandibles and mixes it with saliva to form a pulp that they can shape into a layer for the nest. Nests built in walls may emit a noticeable unpleasant aroma.

Biology

In the spring, each individual queen emerges from hibernation and begins nest building. She builds the nest, forages for food to feed to the larvae, and defends the nest all on her own. Once a queen has produced enough workers to take over these duties, she remains inside the nest producing more offspring. The workers (all of which are females) forage for food and feed the young, as well as expand and defend the nest. Their diet consists mainly of large insects such grasshoppers, flies, and even yellow jackets. They can also exploit a honey bee hive for dead or weaker bees. They continue to enlarge the nest until fall when there may be 300-500 (occasionally up to 1,000) workers. European hornets have a long seasonal cycle. Reproductives (males and females) are produced well into the fall. These reproductives mate and the females will serve as the next generation of queens the following spring. As winter approaches, the workers die off and the future queens abandon the nest and seek shelter in protected areas such as under loose bark, in rotting stumps, and other similar hollows. Every year, the queens select new sites to build new nest and do not reuse abandoned nests. In the fall and winter, these nests can sometimes be viewed from far away in trees or in sheds. It is important to note that the colonies die over the winter and the nests can be removed afterwards.

Behavior

Unlike most other stinging insects, European hornets also fly at night. They can be attracted to lighted windows in homes and may repeatedly fly into the glass with quite a lot of force. This may cause some people to falsely conclude that they hornets are trying to break the glass to enter their home. The hornets are also attracted to porch lights, so the hornets may sometimes be a nuisance for certain outdoor activities. Hornet workers are sometimes noticed chewing bark from thin-barked trees or collecting oozing sap of trees.

Control

Control is best achieved by applying a pesticide directly into the entrance of the nest at dusk or night. Use any aerosol “Wasp & Hornet” spray that propels the insecticide about 10-15 feet. Direct the spray into the nest opening for 5-10 seconds, then move quickly away from the area to avoid any of the hornets that may emerge from the nest. You may need to repeat the treatment the following evening. When spraying, it is advisable to wear a dark long-sleeved shirt and long pants. Do not hold a lit flashlight or stand near car headlights or other lights; the wasps may fly towards them after being agitated. If the nest is in a wall or other inaccessible area in your home, you may want to hire a professional pest control operator to do the work. Whenever possible, remove the nest from the wall. If the wasps are damaging the twigs of ornamentals or fruit trees, a treatment containing carbaryl (Sevin®) to the affected areas of the plants would be advisable. Re-treatment may be needed every 7-10 days, depending upon weather conditions.

More Information

- Bumble Bees of North America: An Identification Guide. Williams, P. H. et al. 2014. Princeton Field Guides, Princeton University Press.

- Carpenter Bees. Michael Waldvogel, M. and P. Alder. 2018. Biting and Stinging Pests, NC State Extension Publications.

- Common name: cicada killer, giant ground hornet, scientific name: Sphecius speciosus (Drury) (Insecta: Hymenoptera: Sphecidae). Stange, L. A. 2012 (revised). Featured Creatures. Entomology & Nematology, FDACS/DPI, EDIS.

- European Hornet. Jacobs, S., Sr. 2010. Penn State Coll. Agr. Sci. Entomology. Fact Sheet.

- Polistes Wasps (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) as Control Agents for Lepidopterous Cabbage Pests. Gould, W. P. and R. L. Jeanne. 1984. Environmental Entomology, Volume 13 (1): 150 –156.

- Extension Plant Pathology Publications and Factsheets

- Horticultural Science Publications

- North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual

For more information on beekeeping, visit the Beekeeping Notes website.

|

David R. Tarpy |

Jennifer J. Keller |

Publication date: Feb. 5, 2015

Reviewed/Revised: Aug. 21, 2024

The use of brand names in this publication does not imply endorsement by NC State University or N.C. A&T State University of the products or services named nor discrimination against similar products or services not mentioned.

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.