This publication highlights the year-of- and year-after-establishment dynamics, management, environment, and productivity for five vegetatively propagated cultivars of bermudagrass grown in spray fields in North Carolina. The data presented and discussed in this publication includes to a great extent the results from on-farm trials conducted in the region (Spearman et al. 2021).

Introduction

Bermudagrass [Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers.] is a widely grown forage species in the coastal plains of North Carolina. In addition, bermudagrass cropping systems are an important component for nutrient management plans of swine farms. In this region, most swine farms rely on lagoons for waste storage. Application of stored waste through irrigation systems on permitted land is the means of waste disposal; hence, these areas are known as spray fields.

There are two criteria that justify the use of bermudagrass-based cropping systems in spray fields. First, bermudagrass has high forage accumulation and nutrient removal compared to other warm-season crop species grown in the region. Second, bermudagrass systems provide the opportunity to increase the timeframe for effluent application by allowing successful overseeding of cool-season annual crops into established bermudagrass. The latter allows more opportunities to dispose of swine effluent to prevent lagoon overflow. Hence, in addition to being a productive and nutritious forage to feed livestock, bermudagrass is also deemed as a nutrient receiver crop.

Bermudagrass hay is consumed readily by livestock. In terms of nutritive value, the total digestible nutrient (TDN) concentration values for bermudagrass hay grown in North Carolina can range from 53% to 70%; crude protein concentration values can range from 6% to 23% according to crop management (Castillo and Romero 2016). As it also occurs with other warm-season forage grasses, high nitrogen fertilizer or effluent application rates on bermudagrass coupled with drought events can, however, result in higher nitrate concentration levels in the plant tissue, which can be potentially toxic to livestock.

Bermudagrass Cultivars

Several cultivars of bermudagrass are readily available to land managers of spray fields in the coastal plains of North Carolina. In addition to high forage accumulation and nutrient removal, desirable attributes of bermudagrass cultivars grown in spray fields include rapid establishment, high nutritive value, and low tissue nitrate concentration. Given the increasing reports of damage from bermudagrass stem maggot (Atherigona reversura), selecting cultivars that are not extensively damaged by stem maggot can be a useful integrated pest management strategy. The dominant cultivars in spray fields are the vegetatively propagated cultivars such as Coastal, Midland 99, Ozark, Tifton 44m, and Tifton 85.

Establishment Year

Bermudagrass fields can be established with seeds (seeded types) and vegetative material such as sprigs (sprigged types) or top growth. Sprigs are vegetative plant parts that contain stolons, crown buds, and rhizomes/runners that are dug from an established field. Each sprig has roots and can produce a new plant when transplanted. A good weed management plan that includes use of herbicides is critical to the success of the establishment of bermudagrass and for control of competition from weeds. Diuron is a pre-emergent herbicide used on sprigged-type varieties that provides fair to good control of crabgrass, crowfootgrass, and goosegrass. Diuron also provides control of certain annual weeds. Consult with your local county extension agent for a weed and herbicide management plan before planting bermudagrass.

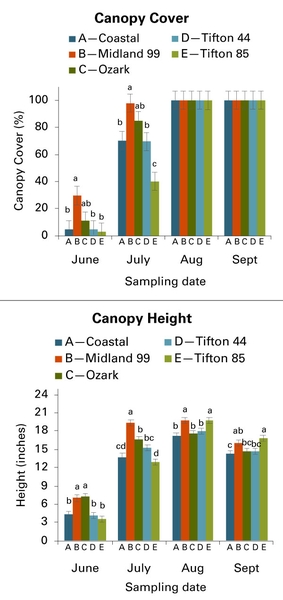

During the year of establishment, the canopy height (defined as the distance from the soil level to the average nonextended and non-compressed height of the canopy) and canopy cover (defined as the percentage of the ground covered by bermudagrass) were monitored for cultivars Coastal, Midland 99, Ozark, Tifton 44, and Tifton 85 bermudagrass grown on a commercially integrated swine operation in Bladen County, North Carolina. The soil series included Foreston loamy sand and Leon sand soil series. Bermudagrasses were planted on April 6, 2016. The canopy height and canopy cover were evaluated once every month from June to September.

By July (three months after planting) of the year of establishment, the canopy cover ranged from 40% to 98%, and the canopy height was ≥ 12 inches for all five cultivars. (Figure 1). A first harvest was possible then by the end of July. One month later, by August, the bermudagrass regrowth approached 100% for canopy cover, and the canopy height ranged between 14 to 18 inches for all cultivars.

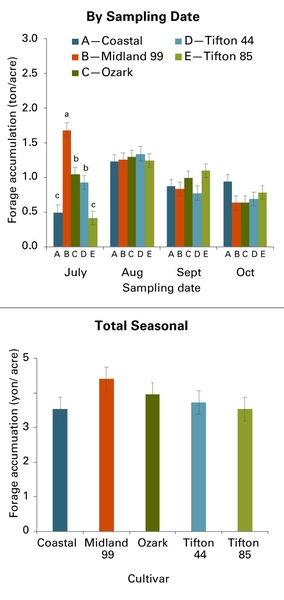

In spray fields, typical swine effluent application dates on bermudagrass fields can range from April to October. With fertigation, bermudagrass may be ready to be defoliated for the first time approximately three to four months after planting in the year of establishment. Although differences in forage accumulation among cultivars were observed during the first harvest event in July, there were no differences among cultivars in the following three harvests (Figure 2). Total annual forage accumulation during the year of establishment (the sum of four sampling events) ranged from 3.5 to 4.5 ton/acre and did not differ among the five cultivars (Figure 2).

Productivity and Stem Maggot Damage

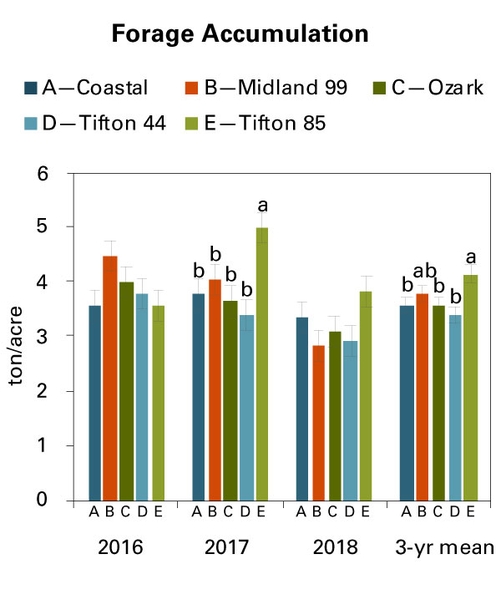

Averaged across three years, Tifton 85 had greater forage accumulation than Coastal, Ozark, or Tifton 44 (Figure 3). These results were similar in 2017, although there were no differences among cultivars in 2016 and 2018. There were high forage accumulation values during the year of establishment (Figure 3). Under the spray field conditions where data were collected, the five bermudagrass cultivars successfully established in the year of establishment and were clipped as early as three months after planting with no apparent deleterious carryover effects as evidenced by their productivity during the two years after the year of establishment. Forage accumulation values in this trial conducted at the spray fields were about twice as great as those reported for bermudagrass in non-spray field areas in North Carolina and were similar to those reported in other states located south of North Carolina where the length of the growing season for bermudagrass is longer.

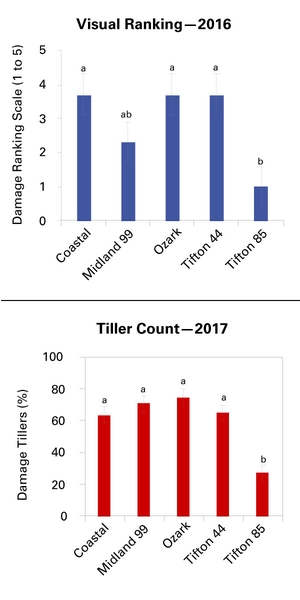

Greater forage accumulation for Tifton 85 in 2017 is attributed to lower stem maggot damage (Figure 4). Tifton 85 had consistently lower bermudagrass stem maggot damage compared to the other cultivars during as determined in the two assessments in 2016 and 2017. Similar results that compared bermudagrass cultivars affected by stem maggot have been reported in greenhouse and field studies conducted in other states located south of North Carolina.

Nutritive Value and Nitrates

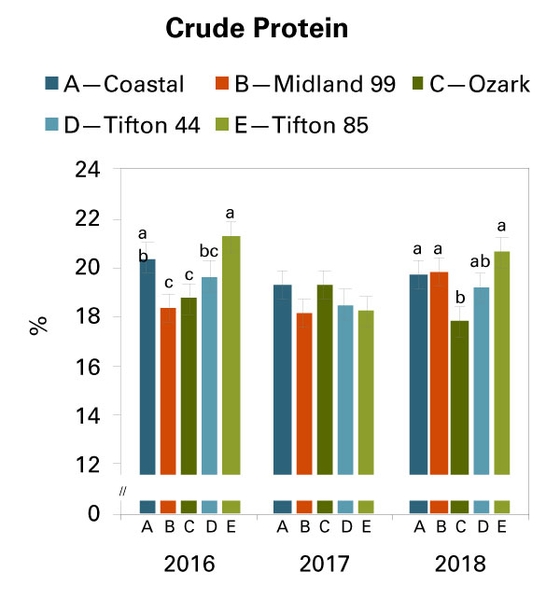

Concentration of crude protein in the harvested tissue ranged from 17.9% to 21.2% with moderate differences among cultivars in 2016 and 2018 (Figure 5). The total digestible nutrient (TDN) concentration did not differ among cultivars with ranges from 61% to 63% across years. Both values, the crude protein and the TDN, would be adequate to meet the dietary needs of a lactating beef cow in the first 90 days after calving. The TDN/CP ratio values for all cultivars were <8 (data not shown), which indicated that there was adequate protein to match the energy in the forage and no need for supplemental protein in the diet (Moore et al. 1991).

Averaged across cultivars and years, the nitrate ion (NO3-) concentration values were 1.1%, 0.5%, and 0.4% in 2016, 2017, and 2018, respectively, with corresponding N loadings of 221, 103, and 276 lb N /acre. The general threshold to feed all kinds of livestock if forage is the sole source of feed is NO3- concentration in the tissue of ≤ 0.5%. Forages with NO3- concentration greater than 0.5% can be fed as a proportion of the rations, and there are several categories proposed in the literature to achieve a feeding strategy (Poore et al. 2000; Hancock 2013). Of the 55 bermudagrass hay lots harvested in this experiment, a total of nine lots had NO3- concentration values ≤ 0.5% with the highest value recorded at 1.5%.

Summary

Vegetatively propagated bermudagrass cultivars Coastal, Midland 99, Ozark, Tifton 44, and Tifton 85 grown during three years in spray field conditions averaged approximately 3.5 to 4.5 ton/acre/year of forage accumulation, with ranges of 17.9% to 21.2% for crude protein and 61% to 63% for total digestible nutrient (TDN) concentrations. Average nitrate ion (NO3-) concentration in the harvested tissue ranged from 0.4% to 1.1% across the years and cultivars. Consistently, cultivar Tifton 85 was the least damaged by stem maggot. These results highlight the high productivity and nutritive value of the five bermudagrass cultivars tested in spray field conditions.

References

Castillo, M.S. and J.J Romero. 2016. Forage quality indices for selecting hay. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Cooperative Extension. AG-824. ↲

Hancock, Dennis W. 2013. Nitrate Toxicity. Circular 915. Athens: University of Georgia Extension. ↲

Poore, M., J. Green, G. Rogers, K. Spivey, and K. Dugan. 2000. Nitrate Management in Beef Cattle. AG-606. Raleigh, NC: NC Cooperative Extension Service. ↲

Moore, John E., William E. Kunkle, and William F. Brown. 1991. “Forage quality and the need for protein and energy supplements.” Proceedings of the 40th Annual Florida Beef Cattle Short Course. ↲

Spearman, Rebecca L., Miguel S. Castillo, and Stephanie Sosinski. 2021. “Evaluation of Five Bermudagrass Cultivars Fertigated with Swine Lagoon Effluent.” Agronomy Journal. 113, no. 3:2567-2577. ↲

Publication date: Aug. 21, 2024

AG-970

Recommendations for the use of agricultural chemicals are included in this publication as a convenience to the reader. The use of brand names and any mention or listing of commercial products or services in this publication does not imply endorsement by NC State University or N.C. A&T State University nor discrimination against similar products or services not mentioned. Individuals who use agricultural chemicals are responsible for ensuring that the intended use complies with current regulations and conforms to the product label. Be sure to obtain current information about usage regulations and examine a current product label before applying any chemical. For assistance, contact your local N.C. Cooperative Extension county center.

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.