Background and Description

Twospotted spider mite (Tetranychus urticae; TSSM) is native to Eurasia but has become established worldwide. It feeds on an enormous variety of plants, including fruit trees, ornamental trees, vegetables, small fruits, shrubs, and many species of weeds. However, in Southeastern apple orchards it is only a sporadic problem.

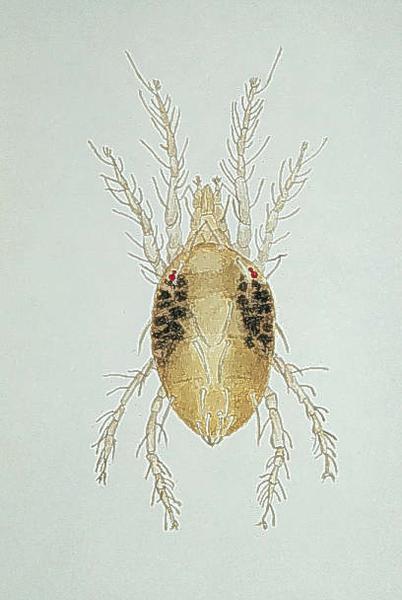

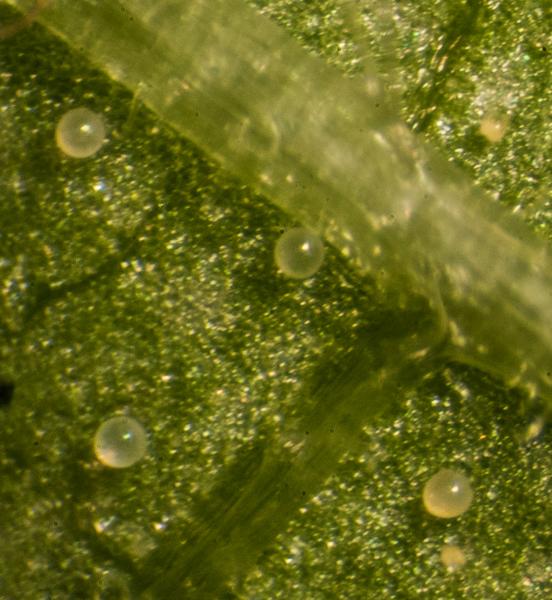

The summer form of adult female TSSM is less than 1/50 inch (0.4mm) long and greenish yellow in color, with two prominent dark spots on either side of the back. These spots may become large enough to cover the body as the mite feeds. (Spots and coloring can be variable, and may lead to confusion with other species.) Eggs are shiny spheres, clear to pale green in color and about 1/200 inch (0.14mm) in diameter. Larvae are about the same size as eggs and are the only life stage with six legs (protonymphs, deuteronymphs, and adults are all eight-legged).

Life History

TSSM overwinter as spotless, orange diapausing females under bark at the bases of trees or in debris on the orchard floor. Shortly before bloom, they move to fresh vegetation (especially vetch and other legumes) and begin feeding on new green tissue. As the weather warms and these hosts dry out, TSSM will move into apple trees, usually infesting the center first. By this time they will have reverted to their typical green, spotted summer appearance and will begin laying eggs on the undersides of leaves. Females lay roughly one egg per day - if a female has mated, the fertilized eggs develop into both male and female mites; if she has not mated, the unfertilized eggs develop into males. Eggs hatch into six-legged larvae, then progress through eight-legged protonymph and deutonymph stages before becoming eight-legged adults. Since generations overlap, all life stages can usually be found simultaneously. There can be nine or more generations per year.

Damage

TSSM feed on leaves. When populations are severe, leaves may lose color or become brown (a condition referred to as "bronzing"). This can lead to fewer fruit, dropped fruit, and lower fruit quality, as well as a lower return bloom the following season.

Many factors determine the severity of a mite infestation, including the time of year when injury occurs, the duration of feeding, the trees' vigor and cultivar, crop load, and weather conditions. The earlier that foliage is injured (i.e., May or early June), the more detrimental the damage will be to tree health. Midseason (i.e., July or later) injury is less significant, but can combine with other stresses to cause fruit drop, poor fruit color, or reduced effectiveness of growth regulating chemicals.

Monitoring and Control

TSSM is rarely a problem in southeastern apple orchards, and most trees are not affected by the relatively small populations that develop.

Bio-control

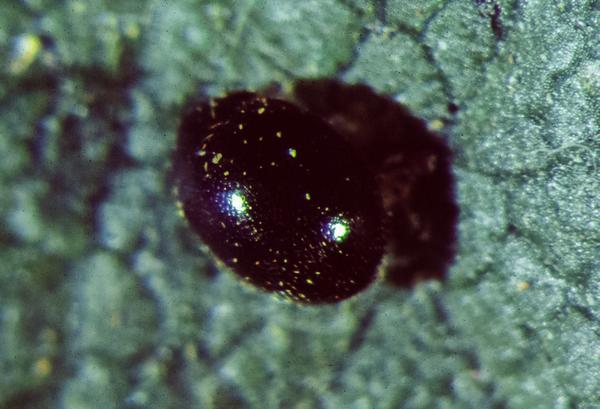

Several beneficial arthropods help keep mite populations below damaging levels. The most common in the Southeast are a phytoseiid mite (Neoseiulus fallacis) and the complex of generalist predators (e.g., black lady beetles (Stethorus punctum) and lacewings). However, recent research in North Carolina suggests that neither of these predators overwinters to any significant degree within orchards, so they must be reestablished in orchards in the spring. Hence, practices that delay the buildup of TSSM and enable predators to increase before mites become a problem will favor biological control. The two most effective practices are applying a delayed dormant oil spray and avoiding insecticides toxic to these predators.

Monitoring Mite Populations

Use a regular monitoring program to follow the buildup of mite populations and to determine if and when supplemental applications of a miticide are necessary to avoid economic damage. Monitor each contiguous block of apples weekly beginning when adult mites first appear (which may vary from mid May to early July). Within each block, examine 5 leaves from each of 10 trees with a visor lens or hand lens. Rather than counting the total number of mites on each leaf, record the number of leaves infested with one or more mites, and estimate the mite density on a per-leaf basis from the table below.

Determining the Need for Miticides

If mite populations reach a density of 5 to 10 mites per leaf (80 to 90 percent infested leaves) decide whether to use biological control or a miticide to prevent mites from increasing to higher densities. Count the actual number of N. fallacis on sample leaves with a visor lens. If the ratio of N. fallacis to TSSM is between 1 to 5 and 1 to 15, biological control is possible. For biological control with S. punctum to occur, the ratio should be 2.5 S. punctum to 1 TSSM. S. punctum should be sampled by counting the number of adults and larvae observed during a timed 3-minute search around the periphery of mite-infested trees. S. punctum larvae must almost always be present if this predator is to control mites. If neither predator is present at sufficient levels for biological control to occur, and mite populations are between 5 to 10 mites per leaf, apply a miticide.

In areas where Alternaria blotch is a problem on Delicious apples, biological control is usually not an option. In the presence of Alternaria blotch, mite populations must be maintained at very low levels to avoid high levels of Alternaria and premature defoliation. If preventive control measures are not used, a modified threshold level of 1 to 2 mites per leaf should dictate the need for miticides.

| % Mite-infested leaves (1+ mite/leaf) | Expected number of mites per leaf |

|---|---|

| 40 | 0.7 |

| 45 | 0.9 |

| 50 | 1.1 |

| 55 | 1.3 |

| 60 | 1.6 |

| 65 | 2.0 |

| 70 | 2.6 |

| 75 | 3.4 |

| 80 | 4.7 |

| 85 | 6.8 |

| 90 | 11.4 |

| 95 | 26.4 |

Publication date: Feb. 23, 2015

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.