Contents

Descriptive Overview of the Literature

Research Themes Related to Diversity and Wildlife-Dependent Recreation

Management Recommendations from the Literature

Research Recommendations from the Literature

Appendix: The 56 Papers Included in the Literature Review

This research was supported by a cooperative agreement between North Carolin State University and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Branch of Human Dimensions.

Direct correspondence to Myron Floyd in the Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management, NC State University, Box 8004, Raleigh, NC 27695-8004.

Executive Summary

The U.S. population continues to urbanize and become more racially and ethnically diverse. By 2043, no single ethnic group will constitute a majority of the U.S. population. Within this pattern, non-white populations tend to concentrate in metropolitan areas. They also tend to encounter more constraints to outdoor recreation, including wildlife-dependent recreation, and they participate at lower rates than non-minorities.

These disparities can have important consequences for individuals, economies, and outdoor recreation management agencies such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. However, there is limited published research on race, ethnicity, and urban diversity related specifically to wildlife-dependent recreation.

To inform development of strategies that respond to increasing racial and ethnic diversity and growth of urban populations, our objective in this study was to review existing social science literature regarding participation in wildlife-dependent recreation by racial and ethnic minorities and urban populations. Our specific objectives were to identify (1) trends in research themes and topics addressed in the past fifteen years of research, (2) methods used in the research, (3) recommendations for management and future research that were stated in the articles, and (4) gaps in the research and opportunities for future studies focused on diversity in wildlife-dependent recreation. Management strategies suggested by the research were of particular interest. Fifty-six relevant articles were identified for analysis using keyword searches of online databases.

Findings showed that fishing was the most frequently studied type of wildlife-dependent recreation, followed by hunting/ trapping, and then non-consumptive recreation. The most common groups sampled were general populations, hunting/ fishing license holders, and on-site recreationists. Hispanic/ Latino populations were the most commonly emphasized racial/ethnic group. More than half of the studies did not emphasize any particular racial/ethnic group. Most studies used quantitative mail or telephone surveys to collect data. The six major themes or topics studied in the last 15 years were participation in recreation activities, socio-demographic comparisons, social-psychological aspects, urban context, barriers to participation, and risk management.

Sixteen management recommendation themes were identified from the literature. The most frequent suggestions were to develop facilities and amenities, target specific racial and ethnic groups, and provide group or social-oriented recreation opportunities. Frequent emphasis was placed on the need to tailor outreach to the local communities and subpopulations of interest. Future research recommendations from the literature included suggestions to continue research on specific ethnic groups (especially Latino populations), conduct longitudinal research, and conduct evaluation studies of programs designed to increase involvement among urban and diverse audiences.

This study provides the first systematic review and synthesis of research on race, ethnicity, and urban populations in relation to wildlife-dependent recreation. Also, the assessment of types and relative frequency of management recommendations can serve to generate particular strategies and tools that recreation agencies, such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, can use to expand their outreach to urban and diverse populations.

Keywords: literature review, race, ethnicity, wildlife-dependent recreation, urban populations

Introduction

Over the next several decades, the U.S. population will change in profound ways. In the United States, every eight out of 10 people live in cities or towns with populations of 50,000 or more (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). Simultaneously, the U.S. population is becoming more racially and ethnically diverse. The most recent census showed that, between 2000 and 2010, the U.S. population experienced a net growth of 27.3 million people: 15.2 million were Hispanic, 3.7 million were African American, 6.1 million were Asian, and 2.3 million were non-Hispanic whites (Murdock, 2014). The U.S. Census Bureau projects that the Hispanic population will continue to grow dramatically. Between 2012 and 2060, the Hispanic population is expected to double, increasing from 53.3 million in 2012 to 128.8 million in 2060. The Asian American population will also double (increasing from 15.9 million to 34.4 million), and the African American population will increase by 50%. As a result, the proportion of non-Hispanic whites in the population is expected to gradually decline, decreasing from 63% to 43% of the population between 2012 and 2060. By 2043, for the first time in the Nation’s history, no single ethnic group will constitute a majority of the U.S. population (U.S. Census, 2012). By mid-century, the projected U.S. population of 439 million will become 46% non-Hispanic white (compared to 69% in 2000), 12% African American (similar to 2000), 30% Hispanic (compared to 13% in 2000), and 12% non-Hispanic Asian (compared to 6% in 2000).

These changes in racial and ethnic composition are already unfolding in large metropolitan areas. These changes are significant because non-white populations in the United States are more concentrated in large metropolitan areas than the overall population. In 2008, the 100 largest metro areas contained 66% of the total U.S. population, of which 77% were non-white populations, including Hispanic Americans (Berube et al., 2010).

Increasing urbanization and ethnic diversification will challenge the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (the Service) and other federal agencies that manage for outdoor recreation. Historically, African Americans, Hispanic Americans, and other non-white population subgroups are less frequent users of national parks, forests, and wildlife refuges. Differences in outdoor recreation participation between African American and white populations in the United States were documented as early as 1962 (Mueller and Gurin, 1962), and attention to this phenomenon has increased in scope and magnitude over the past five decades (Floyd, 2007). Over this time, a general consensus from the literature is that ethnic and racial minorities encounter more constraints to outdoor recreation than non-minorities (Shores, Scott, and Floyd, 2007). As non-white populations increase in share of the U.S. population, land management agencies will be challenged to understand the barriers that limit minorities’ use of their resources for outdoor recreation. An understanding of recreation preferences and desired experiences will also be required for agencies to be responsive to a changing, increasingly diverse population.

Specific to wildlife-dependent recreation participation, as shown in Table 1 (USFWS and U.S. Census Bureau, 2012), non-white population groups are less represented relative to non-Hispanic whites. The Service defines wildlife-dependent recreation as hunting, fishing, wildlife observation and photography, or environmental education and interpretation (H.R. Rep. No. 105- 106, 1997). Current estimates of hunting, fishing, and wildlife recreation participation show that rates of participation vary by race and ethnicity. According to the 2011 National Survey of Hunting, Fishing and Wildlife-Associated Recreation, 18% of Americans who identified as white participated in fishing or hunting, compared to 6% of Hispanics, 10% of African Americans, and 6% of Asian Americans. (USFWS and U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). Thirty-six percent of Americans who identified as white participated in wildlife watching, whereas 11% of Hispanics and African Americans participated. Nine percent of Asian Americans reported participating in wildlife watching. In short, racial and ethnic minorities engage in wildlife-dependent recreation at rates that are approximately one-quarter to one-half those of non-Hispanic whites, as shown in Table 1 (USFWS and U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). A national wildlife refuge visitor survey conducted in 2010 and 2011 revealed that only 4% of visitors to National Wildlife Refuges identified as a race other than white, and only 4% identified as Hispanic (Sexton et al., 2012).

Enduring disparities in wildlife-dependent recreation can have important consequences for individuals and wildlife management agencies. As a result of differential patterns of participation, benefits associated with participating in wildlife-dependent recreation may not accrue equally across subgroups (Gramann, 1996). Individual benefits from outdoor recreation visits include social cohesion, improved mental and physical health, learning and skill development, and overall psychological well-being (Chavez and Olson, 2009; Gobster, 2005; Manning and Moore, 2002; Williams, 2006). In addition to individual benefits, wildlife-dependent recreation has a significant impact on both local economies and the national economy. The 2011 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting and Wildlife-Associated Recreation estimated that Americans spent $145 billion on related expenses, which represents about 1% of the U.S. gross domestic product. Therefore, the lack of racial and ethnic diversity among participants in hunting, fishing, and wildlife viewing has direct economic implications for wildlife and fisheries management. Each state’s fish and wildlife management agency receives federal funding from excise taxes placed on the sale of certain equipment related to hunting and fishing as determined by the Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Programs Improvement Act of 2000. The Service distributes this revenue in proportion to the number of fishing and hunting license sales from each state. States use these funds for land acquisition and wildlife research/management programs. The lack of participation in these activities by growing segments of the population equates to lost opportunities for wildlife management revenue (Floyd and Lee, 2002) as well as political support.

Research can inform efforts to provide outdoor recreation opportunities for urban and diverse populations. The literature on race, ethnicity and outdoor recreation has increased significantly in recent years (Floyd, Bocarro, and Thompson, 2008). However, there is limited published research on race, ethnic, and urban diversity related specifically to wildlife- dependent recreation. In a systematic review of five major leisure journals, Floyd et al. (2008) found that 150 of the 3,369 articles (4.5%) published in five major journals up to 2005 had race or ethnicity as a major focus of the research. They identified 19 topical themes in the research with few related to wildlife-dependent recreation. Those with the most relevance were nine studies grouped within a theme of “outdoor recreation and forest recreation,” and 12 studies that examined “activity participation and preferences and leisure meanings.”

It should be noted that the Floyd et al. study was limited to five primary leisure journals and did not include journals such as Human Dimensions of Wildlife, North American Journal of Fisheries Management, and other broader sources. A broader systematic review of the literature on race and ethnicity in wildlife-dependent recreation can serve to identify trends in use patterns, synthesize findings with relevance to human dimensions of wildlife, and set directions for future research (Jackson, 2004). This review gives particular emphasis to identifying and informing management recommendations to better serve ethnically diverse and urban audiences. Ultimately, a greater understanding of the role of race and ethnicity in wildlife-dependent recreation will help public lands management organizations such as the Service develop programs and policies that promote participation and satisfaction among a more diverse population.

Study Purpose and Objectives

To inform development of strategies to respond to increasing racial and ethnic diversity and growth of urban populations, our objective in this study was to review existing social science literature regarding participation in wildlife-dependent recreation among racial and ethnic minorities and urban populations. Our specific objectives were to identify (1) trends in research themes and topics addressed in past research, (2) methods used in the research, (3) recommendations for management and future research that were stated in the articles, and (4) gaps in the research and opportunities for future studies focused on diversity in wildlife-dependent recreation. Particular emphasis was placed on highlighting management strategies suggested by the research. This publication is organized into four major sections and a conclusion. The first section provides additional background on why ethnicnically diverse and urban audiences remain relevant to the Service and other federal agencies. In the second section, we describe the methods used to identify and analyze studies included in the review. The third section reports findings and the major research themes related to diversity and wildlife-dependent recreation. The fourth section presents specific management recommendations extracted from the literature that relate to providing recreation services for diverse audiences. The publication concludes with a review of recommendations for future research.

Relevance to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Other Agencies

The Service has increased efforts to address the opportunities and challenges natural resources agencies face to adapt to the country’s changing demographics. The Service manages the National Wildlife Refuge System (Refuge System), which administers the largest network of protected areas for the conservation of fish, wildlife, and plants while also providing opportunities for wildlife-dependent recreation. Looking specifically at visitation to National Wildlife Refuges, the disparities in participation discussed above become even larger. As mentioned previously, the national wildlife refuge visitor survey conducted in 2010 and 2011 revealed that 96% of visitors to National Wildlife Refuges identified as white, with only 4% of the total sample identifying as Hispanic or Latino ethnicity (Sexton, et al. 2012).

In the summer of 2010, the Service began creating an updated vision for the future of the Refuge System. More than 100 people from across the Service worked together to craft Conserving the Future: Wildlife Refuges and the Next Generation. This document lays out an ambitious plan for the next decade that addresses opportunities and challenges in the face of a changing American population and conservation landscape. To implement the new vision, nine teams consisting of Service employees were created, one of which was the Urban Wildlife Refuge Initiative team (Initiative). The Initiative aims to increase the Service’s relevancy to urban citizens and contribute to the vision’s goal of diversifying and expanding the agency’s conservation constituency over the next decade.

The Initiative needed to gain a better understanding of factors that facilitate or inhibit connecting urban audiences with wildlife and nature. This publication contributes to a larger study by the Service that sought to identify barriers and strategies to engage urban and diverse audiences in wildlife-dependent recreation. It provides a review and synthesis of the current literature to better understand what is known about barriers, motivations, and potential strategies for engaging diverse urban audiences in outdoor recreation. The larger Initiative research project included interviews with refuge staff and partner organization representatives in urban areas to (1) understand current refuge visitation in these settings, (2) identify programs and strategies that have been successful, and (3) identify institutional factors that promote or impede the ability to connect with urban audiences. A third component included community workshops to gain perspectives from local community representatives about the needs and motivations for participation in outdoor recreation, perceptions of existing barriers, and opinions about strategies to better connect and engage diverse urban residents with wildlife.

Agendas, initiatives, and policy at varying agencies and levels of government beyond the Service reflect the importance of connecting Americans to nature and the outdoors. The National Park Service has implemented research initiatives focused on diverse audiences similar to the Service (McCown et al., 2012), and the U.S. Forest Service has launched the Urban Connections outreach program. Furthermore, in 2011 President Obama launched the America’s Great Outdoors Initiative, a national effort to engage the American people in conservation and recreation (Salazar, 2011). This initiative seeks a collaborative approach with states, tribes, and local communities to reconnect Americans—or connect them for the first time—with the outdoors. It also coincides with the Let’s Move Campaign, championed by First Lady Michelle Obama, and emerging organizations such as the Children & Nature Network, which are focused on increasing opportunities for children’s outdoor play and connections to nature.

In the context of wildlife-dependent recreation, two federal policy statements are directly relevant to expanding opportunities for participation: Executive Orders 12862 and 12898. Executive Order No. 12,862, titled Setting Customer Service Standards (1993), directed executive level agencies and departments that provide significant services to the public to “identify customers who are, or should be served by the agency” and to “survey customers to determine the kind and quality of services they want and their level of satisfaction with existing services.” In addition, Executive Order No. 12,898 (1994) directed all federal departments and agencies to identify and address disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of federal actions on minority and low-income populations. Furthermore, each federal agency was specifically directed to “identify differential patterns of consumption of natural resources among minority populations and low-income populations,” as well as “collect, maintain, and analyze information on the consumption patterns of populations who principally rely on fish and/or wildlife for subsistence” (Exec. Order No. 12,898, 1994).

Methods

This review followed established methods for conducting integrative reviews (e.g., see Bocarro, Greenwood, and Henderson, 2008; Edwards and Matarrita-Cascante, 2011). Studies included in the literature review were located using keyword searches of the complete texts (i.e., not limited to titles and abstracts) of all articles in EBSCOHost, Google Scholar, and other online databases. The primary search keywords were hunt, fish, wildlife-watch, race, ethnicity, urban, metro, Latino, Hispanic, African American, Asian American, and other related descriptors. A broad initial search was conducted that identified potentially relevant articles that met all or most of the systematic inclusion criteria listed below. Those potential articles were used to begin snowball sampling, whereby additional potential articles were identified through their references. Additional database searches were informed by the results of snowball sampling, and both sampling methods were employed simultaneously. These procedures generated approximately 500 potential publications. These potential publications were further examined and were included in the systematic analysis of this literature review if they met all of the following four criteria:

- The publication examined wildlife-dependent recreation. To maintain a manageable scope for this review, “wildlife- dependent recreation” was defined as hunting, fishing, wildlife watching, or wildlife photography. Note that wildlife-dependent recreation did not have to be the central focus of the publication; it just had to be explicitly included in the study in some form.

- The publication included examinations of racial/ethnic minorities, urban populations, or both. This included studies that compare racial or ethnic groups, or studies that examine a single racial or ethnic group, or studies that compare urban and rural populations, or studies that examine only urban populations.

- An empirical analysis was reported.

- The study was published within the last 15 years (i.e., from 1999 to 2014).

Because there was limited research on racial/ethnic and urban diversity in the literature, this review included peer-reviewed journal articles, book chapters, conference proceedings, and conference abstracts to broaden the analysis. However, it is important to note that the goal of this literature review was not to exhaustively locate every publication in existence that relates the topics of race, ethnicity, or urban populations to wildlife- dependent recreation. Instead, the process was designed to explore and characterize how scholars have framed the issues, how the issues have been studied, and what recommendations have been made (Floyd, et al., 2008; Edwards and Matarrita- Cascante, 2011).

The content of each article was assessed and coded using the following variables:

- the type of wildlife-dependent recreation examined (fishing, hunting/trapping, or nonconsumptive recreation, such as wildlife watching or photography)

- whether wildlife-dependent recreation was the primary topic of the article

- the method of data collection (mail survey, telephone survey, on-site survey, semi-structured interview, focus group, or other)

- the study population (general population, license/permit holders, recreation participants, urban residents, rural residents, youth, elderly, immigrants, or non-specified)

- the specific racial/ethnic groups sampled or compared

- the presence of an urban-rural comparison

- the geographic location of the study

In addition, thematic analysis was used to examine three aspects of each paper: (1) the main topic, (2) management recommendations stated in the article, and (3) research recommendations stated in the article. Analysis was performed using a coding process similar to grounded theory, following the method of Strauss and Corbin (1990) and Edwards and Matarrita-Cascante (2011). Key phrases were identified, themes were developed from those phrases, and research topics, methods, and recommendations of each study were grouped according to the most salient and important themes.

It is important to note that hundreds of empirical studies from within the last 15 years that examined some aspect of urban or minority participation in outdoor recreation were identified during the sampling process; however, most of those studies did not specifically mention wildlife-dependent recreation (i.e., they did not meet the first of the four criteria for inclusion, but they did meet the last three). Such papers were not included in the systematic analysis of the literature review. Relevant information from those additional papers, however, is referenced alongside the systematic findings to offer context and additional insight.

Results

Descriptive Overview of the Literature

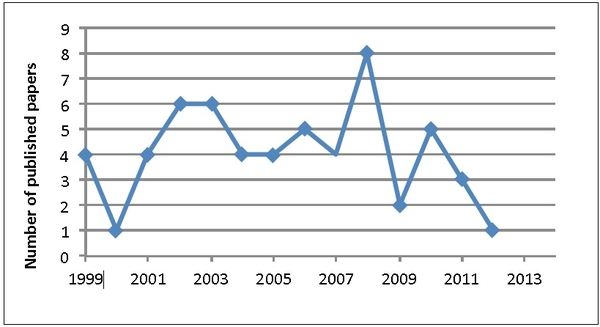

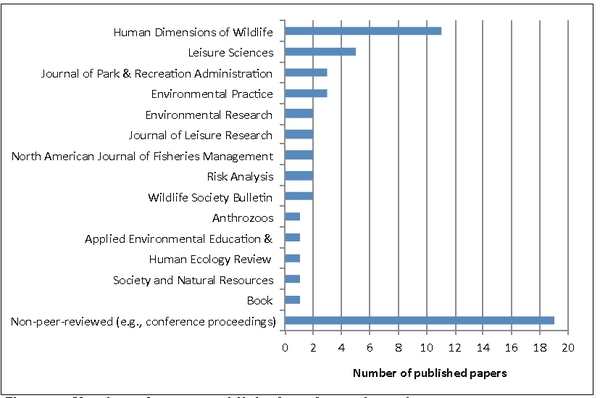

Of the approximately 500 publications examined, 56 were identified that met all four of the systematic inclusion criteria for this review. The publication dates ranged from 1999 to 2014, with a peak frequency in 2008 (Figure 1). The majority of studies were published in peer-reviewed journals and most appeared in Human Dimensions of Wildlife (n=11; Figure 2). Nineteen articles were identified from non-peer-reviewed sources, such as conference proceedings, government reports, and graduate student theses. Fourteen of the non-peer-reviewed articles were from the annual Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium.

Every paper examined some aspect of wildlife-dependent recreation, but only 31 (55%) included wildlife-dependent recreation as a primary focus of investigation. Fishing was the most frequently studied activity, mentioned in 82% (n=46) of published papers; hunting or trapping was studied in 43% (n=24); and nonconsumptive recreation was studied in 54% (n=30). Articles commonly included wildlife-dependent recreation as a secondary focus by examining a wider variety of outdoor recreation activity preferences and including wildlife watching as one activity. Other studies examined people’s values or attitudes towards wildlife as a focal topic. For example, Cronan, Shinew, and Stodolska (2008) examined trail use among Latinos and one of the 14 trail activities included in their survey was watching/ feeding birds or animals (p. 73).

Studies in this review included participants from a wide range of populations and recreation participants (Table 2). The most common groups sampled were general populations of a geographic study area (n=14, 25%), hunting or fishing license holders (n=12, 21%), and on-site recreationists (n=12, 21%). Fourteen publications (25%) included samples with multiple racial/ ethnic minority groups (Table 3). Hispanic/Latino populations were the focus of five studies (9%). African Americans were the focus of three studies (5%), two studies focused on Asian Americans (4%), and one study concentrated on Native Americans (2%). Thirty-one publications (55%) did not feature racial/ethnic content in their findings but were still included in the systematic analysis because they conducted studies of urban populations (Table 3).

| Population Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| General population | 14 | 25 |

| Hunting or fishing license holders | 12 | 21 |

| On-site recreationists | 12 | 21 |

| Subject experts | 3 | 5 |

| Urban residents | 5 | 9 |

| Youth | 3 | 5 |

| Immigrants | 1 | 2 |

| Rural residents | 1 | 2 |

| Vehicle license purchasers | 1 | 2 |

| Multiple categories (e.g., urban youth) | 3 | 5 |

| Not specified | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 56 | 99* |

*Error due to rounding ↲

| Group | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Hispanic/Latino | 5 | 9 |

| African American | 3 | 5 |

| Asian American | 2 | 4 |

| Native American | 1 | 2 |

| Multiple minority groups | 14 | 25 |

| No minority focus* | 31 | 55 |

| Total | 56 | 100 |

*Race or ethnicity was secondary to the main focus of the study or was not mentioned. ↲

Surveys were the primary method of data collection used in the studies. Mail surveys were used most frequently (n=20, 36%), followed by telephone (n=15, 27%) and on-site surveys (n=10, 18%). As would be expected, given the predominant use of surveys, quantitative methods were used in the vast majority of the studies (n=46, 82%). Qualitative methods (e.g., in-depth interviews and focus groups) were used less frequently (n=9, 16%), and one study used both methods.

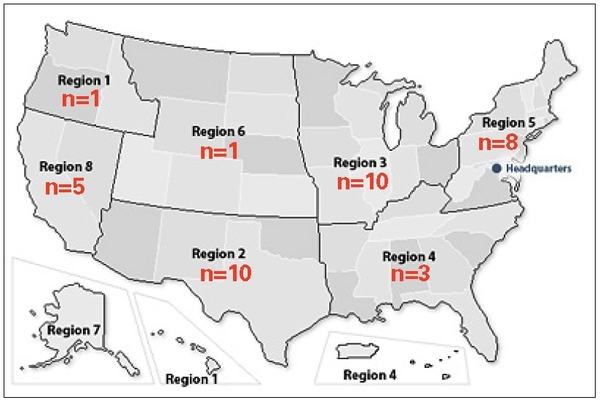

Studies were conducted in multiple regions of the United States. Figure 3 shows the distribution of study locations across the eight Service management regions. As shown in Table 4, most of the studies occurred in Region 2 (n=10, 18%), Region 3 (n=10, 18%), or across multiple regions (n=9, 16%). Regions 1, 6, and 7 had one or less study focused on an area within their boundaries. Five studies (9%) were national in scope (e.g., studies using the National Survey of Hunting, Fishing, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation). Ten studies (19%) were conducted on-site at a recreational area, of which five (9%) were federally managed (e.g., U.S. Forest Service), two (4%) were managed by a city, and three (6%) were under multiple jurisdictions. No studies were identified that were conducted at a national wildlife refuge.

Research Themes Related to Diversity and Wildlife-Dependent Recreation

Thematic analysis of the main topics of each paper produced six main research themes (Table 5). The goal of the analysis was to describe the range of topics in research on wildlife- dependent recreation related to diverse and urban populations. It is important to note that the themes were non-exclusive, meaning that a paper could be associated with more than one theme. The most common research themes were participation in recreation activities(n=48, 86%); socio-demographic comparisons between subgroups (n=39, 70%); and social-psychological aspectsof participation, such as beliefs, values, attitudes, motivations, preferences, opinions, and satisfactions associated with wildlife-dependent recreation (n=36, 64%). Each theme was present in more than half of the papers, indicating a strong overlap. A more detailed description of the six main themes is provided in Table 5.

| Topical Theme | N * | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Participation in recreation activities | 48 | 86 |

| 2. Socio-demographic comparison | 39 | 70 |

| 3. Social-psychological analysis (e.g., motivations) | 36 | 64 |

| 4. Urban context | 19 | 34 |

| 5. Barriers to participation | 10 | 18 |

| 6. Risk management | 6 | 11 |

| Other | 13 | 23 |

*Papers could contain more than one theme; sum of N>56. ↲

1. Participation in recreation activities (n=48, 86%)

The participation in recreation activities theme included studies that focused on activity participation and use patterns. Such studies focused on hunting, fishing, wildlife viewing, camping, park use, and national forest visitation among other activities and behaviors. They examined topics such as the identification of user groups participating in different recreation activities (e.g., Hunt and Ditton, 2002), the manner in which people participated (e.g., McAvoy, Shirilla, and Flood, 2005), or factors influencing participation (e.g., Sali and Kuehn, 2008).

For example, Hunt and Ditton’s (2002) study of fishing participation in Texas found that Anglos (whites) were more likely than African Americans and other racial/ethnic groups to be licensed anglers. They also reported that Anglo males were more likely to begin fishing at earlier ages. Lee and Scott (2011) utilized the 2006 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation to examine participation in wildlife watching. They concluded that race/ethnicity was the strongest predictor of participation in wildlife watching close to home and away from home. For example, being white increased an individual’s likelihood of participating in wildlife watching away from home by approximately two and one-half times compared to non-whites; in addition, a household income of $25,000 or more increased the likelihood of participating in wildlife watching away from home by a factor of two compared to lower income households. Johnson and Bowker (1999) sampled African Americans and whites in the rural South (near the Apalachicola National Forest in Florida). They asked respondents about their levels of activity participation on the national forest’s grounds or other natural areas. No differences were observed between racial/ethnic groups for consumptive recreation such as hunting and fishing. However, whites participated more in camping, hiking, nature observation, canoeing/kayaking, picnicking, and relaxation in natural areas.

Chavez and Olson (2009) reported many similarities among Latino visitors to day-use sites on four Southern California national forests. Similarities were observed in activity participation, the relative importance of site attributes, and perceptions reported about their recreation experiences. At all four areas, common activities were development dependent (e.g., picnicking/barbecuing, camping, and off-highway vehicle riding), natural area dependent (e.g., watching wildlife and driving for pleasure), or water dependent (e.g., stream play and fishing). Using data collected from visitor studies between 1990 and 2011, Le (2012) examined potential differences between non-Hispanic whites and Hispanic national park visitors. The findings showed that Hispanics visited parks in larger groups and traveled less distance to get to parks. Le also reported that among day users, Hispanics reported spending more time in the parks. Hispanics also rated facilities, services, and amenities such as restrooms and staff as more important to their visits than white park visitors.

2. Socio-demographic comparisons (n=39, 70%)

The socio-demographic comparisons theme included studies that compared individuals or groups based on demographic characteristics such as age (e.g., Lee and Scott, 2011), gender (e.g., Sali and Kuehn, 2008), race/ethnicity (e.g., Hunt, Floyd, and Ditton, 2007), and place of residence or urban/rural residence (e.g., Ford, 2008; Mankin, Warner, and Anderson, 1999). Studies that examined just a single socio-demographic group were not included in this theme. Within this theme, comparisons by socioeconomic variables such as income and education (Floyd, Nicholas, et al., 2006; Lee and Scott, 2011) were also found. For example, Dwyer and Barro (2001) found a positive correlation between age and observing wildlife for residents of Cooke County, Illinois. Mankin et al. (1999) reported that metro residents in Illinois had fewer encounters with wildlife and participated in wildlife recreation less than non-metro residents. Sali and Kuehn (2008) compared men and women bird-watchers and found that men took a greater number of in-state and out-of-state bird-watching trips. They also reported that men and women used similar locations but different types of equipment. In another study, Marsinko and Dwyer (2005) examined trends in participation rates in wildlife-associated recreation activities by race/ethnicity and gender. Among other findings, they reported that hunting was the activity with the greatest disparity in participation by gender and race/ethnicity, although other recreation activities had similar participation rates for men and women. Floyd et al. (2006) and Lee and Scott (2011) demonstrated the importance of considering how multiple socio-demographic variables interact to impact participation in wildlife recreation. For instance, Lee and Scott’s study showed that young white men from rural areas had the highest participation in wildlife watching away from home, whereas elderly white women from rural areas, with college educations and higher incomes, had the highest rates of participation in wildlife watching close to home. Based on a statewide survey of Texas residents, Floyd et al. (2006) found that the probability of having ever fished was 95% for young, white (or Anglo), college educated, and high income earning individuals. Respondents that were older than 65, of minority status, female, without a college degree, or with an income below $20,000 were approximately two times less likely to have ever fished. Their estimated probability for having ever fished was 46%.

3. Social-psychological aspects (n=36, 64%)

The social-psychological aspects theme included studies that sought to describe social-psychological aspects of wildlife recreation participation or outdoor recreation. It included concepts such as attitudes (e.g., Mankin et. al., 1999), values (e.g., Manfredo, Teel, and Bright, 2003), motivations and perceived benefits (e.g., Fedler and Ditton, 2001; Schuett et al., 2010), and perceptions (e.g., Dwyer, 2003). Studies involving attitudes and values were oriented towards identifying public opinion about an array of wildlife related issues (e.g., Butler et al., 2003; Manfredo et al., 2003). Investigations of motivation were focused on actual participants or consumers, either license holders (Zwick et al., 2002) or on-site participants (McAvoy et al., 2005). Such studies provide information on underlying meanings, motivations, and perceived benefits of participating in recreation activities.

Ethnic patterns or differences in motivations were found between whites and ethnic minority groups. For example, results from a study using four statewide surveys in Texas indicated that African Americans were more interested in catching large fish, catching larger numbers of fish, and keeping the fish that were caught compared to white anglers (Hunt et al., 2007). Hunt and Ditton (2001) compared the motives of Anglo American and Hispanic American anglers. They observed that escaping stress and being in a natural environment was more important to Anglo Americans, while Hispanic Americans rated achievement as a more important motivation. In a study comparing white and African American anglers in the Mississippi Delta region, Toth and Brown (1997) reported that while white and African American anglers associated similar meanings to fishing, whites placed greater emphasis on sport aspects of the activity, while subsistence was of greater importance to African Americans.

Hutt and Neal (2010) found that urban anglers, who were more likely to be African American, placed greater importance on waters to fish close to home and also preferred site attributes such as stocked fish, restrooms, and clean facilities.

Winter, Jeong, and Godbey (2004) compared three motive domains associated with visiting natural areas—consumption, experiencing nature, and social interaction—among Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Filipino residents in the San Francisco area. Consumptive reasons and social interaction motivations were rated higher among Chinese and Filipino respondents. Chinese respondents placed the highest ratings on nature related motivations. An important contribution of this study was its comparison of four different Asian origin groups and its demonstration of significant heterogeneity within this population.

In a New Zealand study, Lovelock et al. (2011) conducted in- depth interviews exploring how new immigrants to New Zealand engage with nature in protected areas. Cultural values and experiences related to wilderness, nature, and aesthetics from immigrants’ countries of origin were found to be determinants of their likelihood to recreate in New Zealand’s regional and national parks. Immigrants who had wilderness experiences in their countries of origin were more likely to recreate in the parks than those who were unfamiliar with such experiences. Park use by Chinese immigrants was also constrained by aesthetic perceptions: they viewed parks as uncultivated and less aesthetically pleasing than places with structures, monuments, landscaping, or other human-made elements. One key aspect across studies of attitudes, motivations, and perceived benefits is that even when groups (or subgroups) engage in the same activity or use the same recreation settings, their reasons for participation and sources of satisfaction can differ.

4. Urban context (n=19, 34%)

The urban context theme included studies that focused on urban residents or recreation in urban or urban-proximate natural settings (e.g., Burger, Pflugh et al., 1999; Burger, Stephens, Boring, Kuklinski, Gibbons, and Gochfeld, et al., 1999; Chavez and Olson, 2009; Dwyer, 2003). As an example, Burger, Pflugh, et al. (1999) interviewed people who were fishing or crabbing in the Newark, New Jersey Bay Complex about fish consumption behaviors. Fisher, Westphal, and Longini (2010) conducted a similar study in the Calumet Region of northwest Indiana and southeast Chicago. Fisher et al. (2010) determined that two-thirds of their sample reported eating the fish that they caught. Compared to whites, African Americans and Hispanics were more likely to eat their catch and to fish regularly for fish to eat. Similarly, the Burger, Pflugh, et al. (1999) study found ethnic differences in fish consumption. Differences in the information sources used by different racial/ethnic groups about fishing and knowledge of advisories and health risks associated with eating contaminated fish were also found. African Americans and Hispanics were more likely to consume more of their catch and were less aware of the health risks associated with eating their catch. In a study conducted in South Carolina, Burger, Stephens, et al. (1999) obtained similar results. They found that African Americans consumed more caught fish than whites and also consumed larger portion sizes. As mentioned previously, consumption patterns among African Americans exposes them to higher risk of eating contaminated fish.

A study of urban park visitation using surveys of Philadelphia and Atlanta residents included wildlife recreation as a secondary focus (Ho et al., 2005). It found that the perceived importance of wildlife as a preferable attribute of parks differed by an individual’s race/ethnicity. Wildlife was perceived as important significantly more often among whites, Hispanics, and Japanese residents compared to residents who were African American or of Chinese or Korean ancestry. However, all groups rated wildlife as somewhat important (ranging from 1.93 to 2.14 on a three-point scale). Even so, out of six park attributes considered (facilities, ethnic representation, landscapes, wildlife, water amenities, and logistics items, such as parking spaces and signage) wildlife ranked fifth based on mean perceived importance ratings.

Dwyer and Barro (2001) reported on outdoor recreation behaviors and preferences of racial/ethnic groups in Cooke County (Chicago), Illinois, the second most populous county in the United States. They compared representative samples of white (non-Hispanic) Americans, African Americans, and Hispanic Americans on their participation in 43 diverse outdoor activities and use of 20 facility locations. All groups reported that outdoor recreation was important to them, but significant differences were found for 33 of the 43 activities and 13 of the 20 places. There were also significant differences found in site facility preferences, group size and make-up, and number of out of state trips for outdoor recreation among racial/ethnic groups. For example, whites were more likely to observe wildlife, fish, tent camp, prefer a less developed setting, and to recreate out of state. African Americans were more likely to use specific places in Chicago, prefer developed facilities, and were more likely than the other groups to recreate in church and social groups. Hispanic Americans were more likely than other groups to visit the Lincoln Park Zoo and more likely to participate in outdoor activities in groups with adults and children in the family.

Studies by Chavez (2001; 2008) and Chavez and Olson (2009) highlighted use of day-use areas near southern California by Hispanic populations. Consistent with Dwyer and Barro (2001), developed sites with facilities, opportunities for social interaction, and natural elements were found to be important aspects of Hispanics’ recreation experiences.

5. Barriers to participation (n=10, 18%)

The barriers to participation theme focused on barriers and constraints that prevent people from engaging in recreation (e.g., Larson, Green, and Cordell, 2011; Wolch and Zhang, 2004; Zwick et al., 2006).

Zwick et al. (2006) examined parents’ and youths’ perceived opportunities and constraints to participation in a Massachusetts youth hunt. Parents and youth differed in their perceptions of opportunities and activities important in a youth hunt. There were few social barriers to youth participation in hunting, but time constraints related to school, work, and sports most often prevented youth from hunting as much as they would like. Similarly, non-participation in youth hunting was related to lack of time and opportunity rather than social constraints.

In another study involving youth, Larson et al. (2011) analyzed children’s reasons for not participating in outdoor activities. The most frequent reason given was “listening to music, art, reading, etc.” (i.e., essentially indoor activities). A study by Fedler and Ditton (2001) found that, compared to active anglers, anglers who were no longer active or who were “recent dropouts” more frequently rated the time taken up by other activities and too many family and work commitments as the primary barriers to fishing. These results are similar to findings reported by Zwick et al. (2006). In their survey of Los Angeles residents, Tierney, Dahl, and Chavez (1998) found that time and household finances were barriers to use of natural areas. Using data from the U.S. Forest Service’s onsite National Visitor Use Monitoring Survey, Johnson et al. (2007) determined that African Americans were more likely than whites to not participate in preferred activities because of the lack of awareness of recreation opportunities. They also found that user fees were less supported by African American and Hispanic respondents. Previous studies suggest that fees and charges restrict recreation opportunities for low income groups (Burns and Graefe, 2006). These results are consistent with Scott and Munson’s (1994) study in which low income residents indicated they would use parks more if transportation was more convenient and if costs associated with going to parks were lower.

Discrimination is a barrier that can affect where individuals go for recreation and restrict their choices of recreation activities (Gramann, 1996; Sharaievska, Stodolska, and Floyd, 2014). Flood and McAvoy (2007) interviewed 60 members of the Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation in Montana about their use of national forests. Twenty-eight percent of the interviewees indicated encountering other forest users “who showed disrespect for Indian people” as a barrier to their use, the second-most cited barrier following crowding (p. 203). Although reported at a lower percentage, harassment by Forest Service officers (about 10%) was also mentioned. In a sample of nearly 900 of Chicago’s Lincoln Park users, Gobster (2002) found that 14% of African American park users reported experiencing discrimination in the park, compared to 7% of Latinos and 9% of Asian park users. Tierney et al. (1998) found that minority groups (African American, Latinos, Asian Americans) were more likely than whites to express concerns about discrimination when visiting natural areas.

6. Risk perceptions and management (n=6, 11%)

The risk perceptions and management theme included papers focusing on issues such as risk assessment (e.g., Burger, Stephens, et al., 1999), risk perception (e.g., Westphal et al., 2008), or risk communication (e.g., Burger, Pflugh, et al., 1999). These studies sought to identify preferences for fishing or hunting and consumption patterns. In addition, they aimed to determine awareness of risks associated with consuming contaminated fish or game, which was often tied to issues of environmental justice.

For example, Burger (2002) examined consumption patterns and reasons for fishing in the highly industrialized Newark Bay Complex to understand the disconnect between consumption risk advisories and fish consumption. She found that study participants fished mostly to relax, be outdoors, commune with nature, and recreate rather than fishing primarily as a source of food. Ethnic differences in consumption patterns consistent with earlier studies were found; however, there were no ethnic differences among individuals’ reasons for fishing. Overall, 49% of whites did not eat their catch compared to 40% of Hispanics, and 24% and 22% of Asians and African Americans, respectively. About 70% of participants reported eating crabs despite a total ban on both harvesting and consumption because of dioxin-related health risks. People with lower incomes, as well as older anglers, were more likely to consume their catch.

Summary of Research Themes

Despite the challenge of synthesizing findings from studies that examined many different topics using a variety of methods, several patterns emerged. First, national, state-level, and several on-site studies show that the extent of wildlife participation varies by race/ethnicity, gender, and urban/rural locations. Individuals’ participation in different activities was observed in both rural and urban locations, although the extent of involvement and motivations vary. Second, past studies reveal that patterns associated with different socio-demographic subgroups must be considered. These patterns included differences related to particular racial/ethnic groups and subgroups. For example, Ho et al. (2005) and Winter et al. (2004) showed how the perceived importance of site attributes and motivations for participating in recreation varies across different Asian ancestry subgroups. It is important to recognize variations within broad ethnic categories, although few studies have done this. Third, underlying meanings, motivations, and perceived benefits appear to be associated with cultural values among racial/ethnic minority groups. As stated previously, even when groups participate in the same activity or in similar settings, their motivations for doing so may differ (see, e.g., Toth and Brown, 1997). Fourth, wildlife has been shown to be important to urban residents as a preferred park attribute. At the same time, facilities, convenience, and staff appeared to be of greater importance. The importance placed on facilities also applies to urban fishing locations. Fifth, a broad range of outdoor recreation pursuits can be affected by time, financial constraints, lack of awareness, competition from other activities, and other constraints. However, discrimination is a disproportionately significant constraint faced by racial and ethnic minorities. Actual or perceived discrimination can limit participation in certain activities or cause individuals to avoid certain times or locations for outdoor recreation. Finally, study results are consistent in revealing higher fish consumption rates among minority groups and less knowledge and awareness of risk communication.

Management Recommendations from the Literature

Given that the scope of the 56 papers varied from nationwide studies of the general population to site-specific studies of particular subpopulations, it is difficult to synthesize overall recommendations into summaries that could be applied to any time and place. The literature frequently emphasized the need to tailor outreach to the local communities and subpopulations of interest (Bengston et al., 2012; Burger, Stephens et al., 1999; Lu et al., 2010).

Table 6 lists the sixteen management recommendation themes that emerged from systematically reviewing the literature. These themes are non-exclusive, meaning that a paper could be associated with multiple recommendations. The following section provides a detailed description of each of the sixteen recommendation themes. The most common management recommendation themes were to develop facilities and amenities (n=16, 29%), target specific races or ethnicities (n=16, 29%), and provide group recreation opportunities (n=15, 27%). Thirty percent of the papers (n=17) had no management recommendations. Excerpts from studies that highlighted specific strategies are also presented in the following section. It is important to note that these themes were developed from analyzing the 56 papers that met all four criteria for systematic inclusion in this study, including some examination of wildlife-dependent recreation. Additionally, the results of these 56 papers are further scrutinized by presenting them alongside other recommendations from more general studies of outdoor recreation that could potentially be applied to wildlife-dependent recreation.

| Recommendation Theme | N * | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Develop facilities and amenities | 16 | 29 |

| 2. Target specific races or ethnicities | 16 | 29 |

| 3. Provide group recreation opportunities | 15 | 27 |

| 4. Form partnerships with local organizations | 14 | 25 |

| 5. Educate the public/promote environmental justice | 14 | 25 |

| 6. Provide local recreation and target low income residents | 12 | 21 |

| 7. Improve communication channels | 10 | 18 |

| 8. Increase staff diversity and cultural awareness | 9 | 16 |

| 9. Utilize gender-specific outreach | 8 | 14 |

| 10. Provide a safe and clean environment | 6 | 11 |

| 11. Utilize age-specific outreach | 5 | 9 |

| 12. Provide transportation to recreational areas | 5 | 9 |

| 13. Provide signs and services in multiple languages | 4 | 7 |

| 14. Maintain high catch rates for fishing and preferred species | 4 | 7 |

| 15. Increase use of technology to reach youth | 2 | 4 |

| 16. Promote the importance of heritage and tradition in marketing | 1 | 2 |

| No recommendations | 17 | 30 |

*Papers could contain more than one recommendation; sum of N>56. ↲

1. Develop facilities and amenities (n=16, 29%)

The develop facilities and amenities theme included recommendations to target built facilities or equipment towards subpopulations of interest, including equipment loan programs. Such recommendations stem from findings showing that developed facilities, social interactions, and catch opportunities (related to fishing) were important site attributes among minority groups (e.g., Hutt and Neal, 2010; Gobster, 2002).

- Develop facilities and amenities

- tables and seating arrangements for larger groups

- safe and clean restrooms

- shore-based fishing opportunities

- on-site equipment rental service

- partner with recreation outfitter

- mobile equipment supplier

For example, Gobster (2002) makes the following recommendations:

Management that facilitates racially/ethnically based social use patterns might include table and seating arrangements that accommodate larger groups; a simplified information/ permitting system for obtaining picnic areas for organized group festivals; and location and maintenance of restroom facilities throughout the park that provide safe and clean access. (p. 155)

In another example of recommendations related to facilities and amenities, Hunt and Ditton (2002) found that African American and Mexican American anglers fished mostly from the shore and had different preferences for species of fish compared to Anglos and to each other. They recommended that “fisheries managers should pay more attention to shore-based opportunities in African American and Mexican American communities. This means making fishing areas more accessible, developing shore fishing areas with desired amenities, and placing fish attractors to attract desired species close to shore” (p. 62).

Baur et al. (2007) conducted a study of partnership strategies between the National Park Service and community-based organizations. They offered the following managerial solutions to issues that stem from the lack of outdoor equipment due to cost or lack of knowledge:

- Offering an on-site equipment rental service. Either existing vendors or the NPS could offer such a service, perhaps at a discounted rate to low-income visitors.

- Another way to accommodate participants is to partner with recreation outfitters, offering equipment rentals to community and/or low-income group participants.

- One group suggested offering a mobile equipment supplier that NPS staff could use to meet groups at various sites and provide them with necessary equipment. (p. 36)

2. Target specific racial or ethnic group (n=16, 29%)

The target specific racial or ethnic group theme included recommendations that were related to a particular racial or ethnic group. Either the article identified a subgroup that should be targeted, or it offered strategies on how to target a specific subgroup. Racial and ethnic groups discussed in the literature were typically categorized as white, African American, Hispanic, Asian American, and Native American or American Indian.

Specific recommendations pertaining to African Americans were found in 10 studies (18%). Hutt and Neal (2010) made the following recommendation:

Fisheries agencies managing urban fisheries should continue to target African-American anglers as they appear to be more dependent on urban fisheries resources; and have been shown to have catch-related attitudes, preferences, and angling motivations that are different from those of their white counterparts. (pp. 99-101)

Because many African Americans used the Apalachicola National Forest in Florida specifically for fishing, Johnson and Bowker (1999) stated that “fishing seems to be a ’pull’ factor that recreation managers could concentrate on to increase African American visitation to the Apalachicola National Forest. Using this information, managers could direct additional resources to improving fishing venues” (p. 34).

Recommendations targeted towards Hispanics come from 10 studies (18%). For example, Chavez and Olson (2008) indicated that users of urban-proximate natural forests, including Latinos, expressed concern about litter on roadways and in picnic areas, graffiti, and tree carving. They suggested that “managers should focus on keeping sites free of litter and graffiti” (p. 73). To introduce Latinos and African Americans to first time fishing experiences, Floyd et al. (2006) recommended that “efforts to introduce fishing to Latinos and African Americans should focus on intrapersonal (e.g., increasing knowledge and familiarity) and interpersonal (e.g., providing partners or peer-groups) constraints to provide satisfying and comfortable first and early experiences” (p. 365).

2. Target specific races or ethnicities

- African American

- Utilize fishing as a “pull” activity to increase visitation.

- Stock fish.

- Hispanics

- Keep sites free of litter and graffiti.

- Increase knowledge and familiarity.

- Provide information through Latino organizations (e.g., farm workers associations, health clinics, community centers, small businesses).

- Provide information through television, especially Univision (Spanish language channel).

- Asian Americans

- Utilize existing organizations to deliver information.

- Trust with key informants is important.

- Publicize health, culture, and educational benefits.

- Native Americans

- Understand history of past use of lands and how it became public land.

Recommendations targeting Asian Americans were found in 10 papers (18%). A study by Burns, Covelli, and Graefe (2008) reported recommendations from Asian American focus group participants:

Participants all agreed that utilizing existing Asian American organizations as a means to inform the community about recreation opportunities would be helpful. This includes using social service agencies, Asian restaurant associations, churches, and schools. One suggestion was to hang fliers and posters in Asian restaurants and stores. The issue of trust within the community is important to acknowledge.

Participants suggested that outdoor recreation agencies need to create trust with key informants within the community to pass along the benefits of outdoor recreation. This may be achieved by going to Asian community fairs and using social service agencies. Participants also suggested publicizing the benefits of recreation to the community. Some benefits that may be appealing to the Asian American community include health, culture, and education. (p. 132).

One study gave management recommendations focused on Native Americans. In this case, McAvoy et al. (2005) made the following remark:

Any attempt by managers or researchers to understand how American Indians relate to national forests and other protected lands must consider the history of how Indian people used those forests in the past, and how some of the forests came to be designated as public lands. (p. 82)

3. Provide family and group recreation opportunities (n=15, 27%)

The provide family and group recreation opportunities theme included recommendations focused on reaching out to individuals and communities through families or large organized groups. In some cases this applied to Hispanic families that typically recreate in large extended family groups. It also included recommendations to provide opportunities for recreationists to socialize. Tseng and Ditton (2007) stated that

because of Hispanics’ strong family attachment to the nuclear and extended kinship network, a secure and supportive social space for shared experiences with family and extended family is a more important management goal than focusing on the size and nature of the fish and the sporting experiences provided. (p. 238)

In response to the preference for group participation among African Americans visiting a southern national forest, “managers could emphasize that the forest provides opportunities for group-related activities for social and civic clubs and religious groups” (Johnson and Bowker 1999, 34).

Kuehn (2006) focused attention on parental involvement as a key to attracting children to fishing:

The importance of support by friends and family for female children indicates that strategies for increasing participation by children need to focus on parental fishing involvement as well. Educating parents about how their support affects their children’s fishing participation could be useful for encouraging parents to take their children fishing more often. Creating family fishing events could be an effective strategy. (p.417)

3. Provide family and group recreation opportunities

- Focus on providing social space rather than sporting experiences.

- Educate parents about how their support affects their children’s participation.

- Create family fishing events.

- Show single-parent families in advertisements.

- For youth, provide social events such as fishing derbies and teen retreat weekends.

In light of the increased number of female-headed households, Johnson and Bowker (1999) made the following suggestion:

Federal land managers should consider that some of the more traditional “mother-father, two kids” activities may give way to those that include a single female adult and children. For some outdoor recreation markets, signs and brochures advertising recreation opportunities in national forests could also include promotional material that show one adult and child or children. (p. 36)

To target teens, Kuehn (2006) recommended that

programs designed to increase fishing participation should provide social interaction as well as increased fishing opportunities....Efforts to organize outdoor activity groups and social events such as fishing derbies and teen retreat weekends may help maintain female fishing involvement during this life stage and may be equally effective for males. (p. 417)

4. Form partnerships with local organizations (n=14, 25%)

The form partnerships with local organizations theme included recommendations to provide opportunities, services, and information in partnership with other community organizations such as schools, Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts, non-profits, and faith-based organizations.

Bengston et al. (2012) provided an example of a partnership with the Hmong community that identified the need for partnership to be viewed as a long-term effort and the need to incorporate cultural values of the community. They concluded that successful partnerships must rely on strong relationships with local cultures:

Environmental educators and researchers from the mainstream culture cannot succeed in developing culturally appropriate environmental education approaches without fully partnering with the target community. The community of interest must be centrally involved every step of the way in designing effective approaches to ensure that the most important messages are identified and that they are communicated in ways that are both memorable and culturally harmonious. (p. 7)

4. Form partnerships with local organizations

- Involve community organizations in planning processes.

- Integrate outdoor/fishing skill development courses in school curriculum.

- Include or enhance outdoor/ fishing skill development activities in youth organizations.

- Work with partner organizations who can provide on-site guidance about flora and fauna.

Kuehn (2006) identified social and psychological factors that influenced fishing participation among a sample of Lake Ontario anglers and made the following recommendation:

Because of the importance of skill development on childhood fishing participation, parents should be encouraged to bring their children fishing at locations that enable their children to easily catch fish (e.g., panfishing ponds). Skill development could also be enhanced through the inclusion of outdoor/fishing skill development courses in school curriculums, and by including or enhancing fishing skill development activities in youth organizations. (p. 417)

In their analysis of data from the National Survey of Hunting, Fishing and Wildlife-Associated Recreation, Lee and Scott (2011) found that race was the best predictor of wildlife watching activities. They concluded that “outreach efforts should be designed with an eye to reaching out to people of color. Blacks and Hispanics, for example, may be attracted to wildlife watching sites that include employees and volunteers who look like them” (p. 341).

Baur et al. (2007) developed an extensive list of recommendations related to partnerships based on interviews with National Park Service (NPS) staff and staff from community organizations in Los Angeles. The following recommendations were directed to the NPS:

- Develop materials specifically for visitors new to the outdoors.

- Conduct more NPS staff visits to local communities.

- Increase information exchange through partnerships and conduct “market” research to determine how best to attract and engage currently underserved audience members.

- Directly involve CBOs [community based organizations] in planning decisions.

- Explore and support internal innovation, including alternative funding sources. (p. 47)

5. Educate the public/promote environmental justice (n=14, 25%)

The educate the public/promote environmental justice theme was formed from recommendations to educate the public about various issues, which include recreational opportunities, ecosystem services, and environmental risks. Studies in this theme tended to recognize that low income and racial and ethnic minority groups often experience disproportionately greater risk of exposure to environmental hazards (Floyd and Johnson, 2002). This theme considered ethnic differences in fish consumption, potential exposure to contaminants, and dissemination of risk information.

5. Educate the public/promote environmental justice

- Educate people about the benefits of nongame species as part of programs that are primarily designed to improve hunting skills.

- Provide effective risk communication on exposure to contaminants for groups that exhibit higher levels of fish consumption.

- Educate the public using students, interns, local residents, or a Master Angler program similar to Master Gardeners.

- Be aware of distribution and quality of facilities, services, programs, and staff, paying attention to areas that serve minorities.

Chavez (2008) found that on-site Latino respondents at a Forest Service day-use site felt that more areas should be set aside for recreational and resource protection. Respondents expressed preferences for protection of water quality, protection of wildlife, improved air quality, protection of plants, visitor safety, watching wildlife, swimming, camping, picnicking in developed sites, scenic values, stream play, and educational purposes.

Chavez (2008) recommended that

managers of these natural areas in southern California might want to consider communication and educational programs focusing on describing the benefits to Latinos from natural areas, especially emphasizing regulating and cultural services. It might be an opportunity to increase knowledge levels about what natural areas do for people. Awareness can lead to an informed public and protected natural areas. (p. 162)

Reflecting on their comparison of metro and non-metro residents’ opinions about wildlife in Illinois, Mankin et al. (1999) concluded that their study showed “a strong need for environmental education” (p. 472). They stated that

environmental issues are becoming important to many people, but the extent of superficial knowledge, misconceptions, and lack of diverse experiential involvement by citizens are a serious concern. More emphasis could be placed on the benefits gained by nongame wildlife species through programs that are primarily designed to improve hunting. Thus, managing all types of wildlife needs to be conveyed in the context of the goal of maintaining the integrity of ecosystems. (p. 472)

Burger, Pflugh et al. (1999) found that the dissemination of information about the risks of eating fish and crabs in the Newark Bay area has not worked as well as authorities believed. Due to differences in consumption patterns, risks were greater for Hispanics and African Americans than whites. Rather than discourage fishing, the authors recommended promoting alternate cooking methods or other risk-reduction methods.

During the interviews, respondents changed their perceptions of risk when presented with a direct statement from the interviewer. As a result, the researchers concluded that

strategies must be developed to inform the public about the risks of consuming blue crabs and particular species of fish...a campaign that included hiring students, interns, or local residents to talk to fishermen about the hazards from fish and crab consumption might be effective. Further, such people should be fluent in Spanish in the Newark Bay Complex, and comfortable with the Hispanic culture. (p. 227)

Westphal et al. (2008) suggested developing a “Master Angler” program, modeled after the Cooperative Extension’s Master Gardener program, to reach urban anglers with risk communications:

“Master Anglers” could recruit experienced anglers and offer them classes in fish- and fishing-related subjects including local fish consumption risk information. Like Master Gardeners, Master Anglers would then share their expertise with others in both formal and informal settings. The great advantage of such a program is that it provides a mechanism for disseminating information along the proven and trusted informal social networks that already exist in recreational fishing communities. (p. 60)

6. Provide local recreation and target low income residents (n=12, 21%)

Several studies recommended providing outdoor recreation opportunities closer to where people live as a strategy to overcome barriers to participation, especially income and financial barriers. This recommendation suggests that these opportunities must be provided by local recreation agencies, non-profit community organizations, or partnerships involving multiple organizations. Low- or no-cost options were seen as important to avoid pricing out certain groups.

6. Provide local recreation and target low income residents

- Direct efforts to specific non- Anglo communities, not just to large urban areas.

- Focus on close-to-home, day- to-day environments where people encounter wildlife.

- Promote rural angling opportunities close to urban centers as an escape.

- Consider the impacts of fees for recreation, particularly for minorities and women.

Based on their study of fishing, Floyd et al. (2006) reported that income was a key predictor for a person ever having a fishing experience, but it was less important for continued participation. Thus, they concluded that people are more likely to participate if opportunities “exist within close proximity to home and are relatively affordable” (Floyd et al., 2006, 365).

Other researchers have recommended similar strategies for educational programs. According to Van Velsor and Nilon (2006, 368), “Wildlife professionals can help foster an enduring interest in and connection to wildlife by developing programs and materials that reach urban children and their parents and that focus on the day-to-day environments where most of our participants encountered wildlife.”

According to Hunt and Ditton (2002),

Fisheries programs and services seeking to ‘‘reach’’ minority group members should direct their efforts not only to large urban areas where most minorities live but also to the non-Anglo communities there. Providing fisheries resources and conducting outreach activities ‘‘ just anywhere’’ in urban areas will not suffice because people tend to participate in their own communities with members of their own racial- ethnic groups. (p. 61)

Relating to federal land management agencies that charge entrances fees, Johnson and Bowker’s (1999) comments should be considered. They noted that agencies “should recognize that the implementation of such programs may have differential effects on minorities and women,” and that “female-headed families in particular may be priced out of some outdoor recreation markets if fees are required” (p. 24).

7. Improve communication channels (n=10, 18%)

Ten studies recommended developing strategies related to disseminating information to diverse subpopulations or receiving information from them. In most instances, emphasis was placed on using communication channels within various communities. For example, a focus group with Latinos conducted by Burns et al. (2008) led to the following recommendations concerning use of national forests: use Spanish language television and newspapers, advertise for outdoor recreation with Latino models, and utilize local community organizations (e.g., health clinics, farm workers associations, and small busineses). Other suggestions included developing a calendar of events to coordinate local, state, and federal recreation events and using youth to reach parents who may have limited English skills.

7. Improve communication channels

- Simplify the information/ permitting system for organized group festivals.

- Develop materials specifically for visitors new to the outdoors.

- Increase staff visits to local communities.

- Send information home with schoolchildren to be read or translated to parents.

- Develop a calendar showing local, state, and federal recreation events in the area.

- Utilize pre-existing informal social networks

- Advertise using material that depicts people from targeted communities.

For urban national parks, Baur et al. (2007) recommended that park staff and local community organizations identify and visit locations within communities to conduct educational programs. They also suggested developing a website and print materials targeted to first-time visitors to include information such as

- what to expect in parks for those who may have never visited the park;

- information on specific locations, such as trails, services, and facilities;

- common misperceptions;

- what to bring;

- answers to frequently asked questions. (p. 34)

Baur et al. (2007) also recommended that the NPS use a phone- based information access number where park information can be obtained.

8. Increase staff diversity and cultural awareness (n=9, 16%)

Researchers suggested that agencies should increase the cultural awareness of their staff through training programs, by hiring staff from diverse ethnic groups, and by using student interns from racial/ethnic minority groups. Although there have been no studies that examined the effect of staff diversity on visitor diversity, increasing ethnic diversity of staff is an often-suggested strategy for reaching minority audiences (Allison and Hibbler, 2004). For example, Baur et al. (2007) indicated that “having greater staff diversity will help minority visitors and NPS staff relate more readily to one another” (p. 37). They also listed benefits of using student interns:

Student internships are a low-cost option for increasing minority representation at national parks. Internships offer youth a hands-on learning experience and the opportunity to explore a potential career path. Interns also have the opportunity to gain an in-depth exposure to the parks while helping the NPS build their workforce by recruiting more ethnic and other minority groups into a field lacking in diversity. (p. 37)

8. Increase staff diversity and cultural awareness

- Hire more bilingual and racial/ethnically diverse staff to lessen perceptions of discrimination and improve service to diverse clientele.

- Recruit minority youth for student internships.

- Provide staff with ongoing cultural competency training to reduce unintentional stereotypes.

When adding staff or interns is not feasible, Baur et al. (2007) provided cultural competency training as another option for increasing staff awareness of diverse cultures. In an urban park setting, Gobster (2002) discussed the benefits of having a diverse staff and provided the following recommendation:

Police and park supervisors should make their staffs more sensitive to the possibilities that their language and actions can discriminate against certain groups, or be perceived as such...In parks like Lincoln [Chicago, Illinois] with large concentrations of certain minority groups, staff of the same race/ethnicity, and in some cases those who speak the same language, could go far in serving clientele and lessening discrimination, real and/or perceived. (p. 156)

9. Utilize gender-specific outreach (n=8, 14%)

Gender-based strategies were mentioned primarily as a means to increase participation among women in wildlife-dependent recreation, but some studies also included male-specific strategies. Floyd et al. (2006) concluded,

Programs that introduce women and girls to fishing or provide opportunities for women and girls to continue participation should continue to receive financial and other forms of support. Attention should be given to the unique circumstance of Latinas and African American women. (p. 365)

9. Utilize gender-specific outreach

- Market sharing knowledge to male birdwatchers and bird- watching around the home to female birdwatchers.

- Focus on the social nature of fishing to increase female participation; for males, focus on social and sporting aspects.

- Consider the unique circumstance of Latinas and African American women.