NOTE: An invasive tick species, the longhorned tick (Haemaphysalis longicornis) was confirmed in Polk County, NC in late June 2018. This species is native to Asia but has spread to other countries and has been found in Arkansas, New Jersey, Virginia, and West Virginia. The longhorned tick has been found on a number of wildlife hosts including deer, opossums, and raccoons, but it also feeds on dogs, livestock, and people. High tick populations on livestock can have significant impact on their growth and health. The ticks also transmit a number of pathogens that affect livestock as well as people. Control of these ticks is the same as employed for the ticks commonly found in North Carolina and described below.

Introduction

Ticks have long been pests of humans, domestic animals and wildlife in North Carolina. They attach to a living host and feed on the host’s blood. In doing so, they may transmit disease-causing bacteria or viruses that cause Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Lyme disease, both of which can have serious consequences for humans. This publication will help you identify the most common species of ticks found in North Carolina and the diseases that they may transmit. It also describes ways you can protect yourself from ticks outdoors and control ticks in your home.

Tick Biology and Behavior

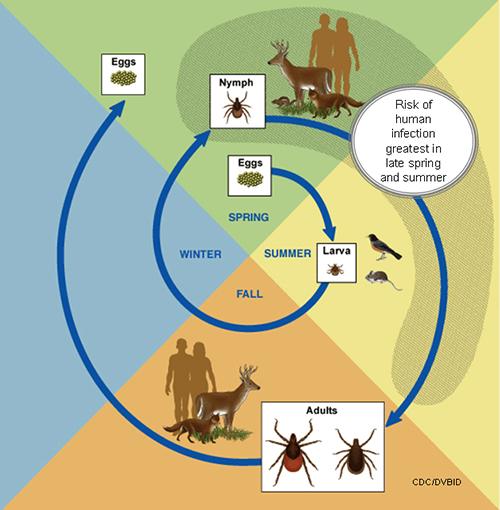

Ticks are related to mites and spiders. They have four stages in their life cycle: the egg, the larva, nymph, and adult stages (Figure 1). Larva, nymphs and adults look simiilar except that the larva only have six legs and with some tick species, color patterns and markings may differ betwen the adults and immatures. After hatching from the egg, the tick must take a blood meal to complete each stage in its life cycle. Each stage of the tick usually takes a blood meal from a different host. For most ticks, each blood meal is taken from a different type of host.

Ticks are usually most active in the spring, summer, and fall; however, the adults of some species are active in the winter. When they seek a blood meal, ticks engage in "questing" behavior.(Figure 2) ticks move from leaf litter or from a crack or crevice along a building foundation, or from another protected area to grass or shrubs where they attach themselves to an animal as it passes. If a host is not found by fall, most species of ticks move into sheltered sites where they become inactive until spring. Once a tick is on a host, it crawls upward in search of a place on the skin where it can attach to take a blood meal. The tick’s mouth parts are barbed (like a fish hook), making it difficult to remove the tick from the skin. In addition, the tick produces a glue to hold the mouthparts in place. The female mates while attached to a host and usually feeds for 8 to 12 days until it is "engorged" (full). By the time it finishes feeding, the female may increase in weight by 100 times (Figure 3). A male tick may attach, but it does not feed as long as the female. The male tick may mate several times before dying. After mating and feeding, the female tick drops to the ground where it lays a mass of eggs in a secluded place such as in a crevice or under leaf litter. Shortly after laying an egg mass, which may contain thousands of eggs, the female dies. The eggs hatch in about two weeks, and the life cycle begins again. Depending upon the species of tick, the life cycle may take as little as a few months or as much as two years.

Common Ticks in North Carolina

Here are the most common species of ticks found across North Carolina:

The American Dog Tick

The adult American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis, (Figure 4) is active in the spring, summer, and fall. It lives along woodland paths, in recreational parks, farm pastures, wastelands, and other shrubby habitats in rural and suburban areas of North Carolina. In each stage of its life cycle, this tick may feed on a different animal. For example, the larvae feed only on white-footed field mice and meadow voles or pine voles, whereas nymphs prefer medium-sized mammals such as opossum or raccoons. Adults prefer humans and dogs as hosts. In North Carolina and throughout the southeastern United States, the American dog tick is the vector of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. However, this species does not transmit Lyme disease. The American dog tick is found throughout North Carolina, but it is most common in the Piedmont area.

The Brown Dog Tick

Rhipicephalus sanguineous, the brown dog tick (Figure 5) occurs throughout North Carolina and may be active year round. In all stages, it feeds almost exclusively on dogs and rarely attacks people. Brown dog tick females may lay egg masses in cracks and crevices along building foundations, in pet kennels, and in homes. After a few weeks, you may find several thousand larvae climbing on walls, draperies, or furniture. When uncontrolled in kennels, populations of the brown dog tick may grow to extremely high levels.

The Lone Star Tick

All stages of Amblyomma americanum, the lone star tick, (Figure 6) readily feed on people and large wild or domestic animals such as deer and dogs. Adults and nymphs are abundant in the spring and summer months. The mite-like larvae of this species, commonly called seed ticks, are abundant in the fall. In this stage, the lone star tick readily attacks humans. This tick is found in habitats similar to those of the American dog tick. Bites from the lone star tick can result in an illness called STARI (Southern Tick Associated Rash Infection) which exhibits a rash similar in appearance to that seen with Lyme Disease. However, this disease is not caused by the same organism that causes Lyme Disease nor has it been linked to the same arthritic, neurological, or chronic symptoms associated with Lyme Disease. The lone star tick also transmits bacteria that cause erhlichiosis. It occurs predominantly in the coastal plain, but it may be found in the North Carolina Piedmont. Recent research has also tied the lone star tick to the "alpha-gal allergy" where the tick bite can result in the person developing an allergy to mammal meat (beef, pork, lamb, venison, rabbit, etc.). For more information about alpha-gal, visit the CDC's Alpha-Gal Allergy.

The Black-Legged Tick

Larvae and nymphs of Ixodes scapularis, the black-legged tick (Figure 7), feed on lizards and small mammals. The nymphs and adults attack small and larger mammals including dogs and deer. Adults are active in late fall, in early spring, and in winter when temperatures rise above freezing. The black-legged tick is found in the same habitats and regions of North Carolina as the lone star tick. It is the vector (transmitter) of the bacterium that causes Lyme disease.

Diseases Transmitted by Ticks

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

Also known as tick typhus, Rocky Mountain spotted fever is caused by a bacteria-like microorganism, Rickettsia rickettsii. Rocky Mountain spotted fever rickettsiae are acquired by an American dog tick when it takes a blood meal from an infected animal. These bacteria are not harmful to most wild and domestic animals, but they are extremely pathogenic to humans and dogs. Rocky Mountain spotted fever is normally a disease of wild animals, but people can be infected while camping or hiking in tick-infested areas if they are bitten by an infected tick. In addition, pets may carry an infected tick into the family living area. The disease organisms can also be passed through the egg of an infected tick and from stage to stage in the life cycle. Fortunately, only a small percentage of American dog ticks found in nature are infected. Symptoms of Rocky Mountain spotted fever include headache, fever, chills, aches, pains, and sometimes nausea. These symptoms are usually accompanied by a rash that starts on the wrists and ankles. Early treatment of Rocky Mountain spotted fever with antibiotics can prevent severe illness, a person exhibiting any of these symptoms 2 to 14 days after a tick bite should consult a physician at once. If left untreated, Rocky Mountain spotted fever can cause death.

Lyme Disease

Lyme disease is caused by a spiral-shaped bacterium (called a spirochete), Borrelia burgdorferi. The bacterium is transmitted through the bite of an infected tick. Lyme disease was recognized as a distinct disease in 1975 after several children, living close to each other in the town of Old Lyme, Connecticut, developed arthritis. The disease is prevalent in the northeastern United States where the black-legged tick, lxodes scapularis (formerly called the deer tick, Ixodes damnini) is the vector of the Lyme disease spirochete. The black-legged tick in the Southeast does not tend to bite humans and as a result many fewer cases of Lyme disease are found. The lone star tick does readily attack humans, but only a small number of spirochete-infected ticks have been collected in the Southeast. Like Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Lyme disease is indigenous to wild animals. Lyme disease has been divided into three clinical stages.

Stage I involves a rash and flu-like symptoms. Within 30 days of infection, a characteristic rash ("erythema migrans") forms at the site of the tick bite. However, 20% - 30% of Lyme disease patients do not exhibit the rash, which often delays diagnosis of the disease. Erythema migrans may occur as an irregular-shaped red blotch or it may consist of a bright red ring around the bite that gradually expands over several days and clears in the center to form a bull’s-eye pattern. The rash can vary in size from 1 to 18 inches. Later, secondary blotchlike skin lesions may occur away from the site of the bite as the spirochete organism spreads. The rash is usually accompanied by fatigue, a headache, a stiff neck, muscle aches and pains, and a general feeling of discomfort.

Stage II, which occurs during the next several weeks, includes cardiac and neurological symptoms. Neurological complications occur in about 15 percent of the patients and can involve encephalitis (inflammation of the brain), radiculitis (inflammation of the nerve roots), and Bell’s palsy (transitory facial paralysis). In most instances, these symptoms completely disappear after lasting several months. Cardiac abnormalities occur in about 8 percent of patients. The symptoms include dizziness, shortness of breath, and heartbeat irregularities that may require installation of a pacemaker. Within several weeks these symptoms usually disappear.

Stage III is distinguished by arthritic problems that may appear as long as two years after the rash. Patients may experience pain, swelling, and elevated temperature in one or more joints. Some patients may also exhibit sleepwalking, loss of memory, mood changes, and inability to concentrate. Lyme disease and its complications can be effectively treated with antibiotics. Physicians use different antibiotics against each stage of the disease. With early treatment, the course of Lyme disease is shortened and the occurrence of late complications, such as arthritis, is reduced. Therefore, it is important to diagnose Lyme disease and administer antibiotic therapy quickly.

Ehrlichiosis

Ehrlichiosis is caused by several bacterial species in the genus Ehrlichia (pronounced err-lick-ee-uh) which have been recognized since 1935. Human ehrlichiosis due to Ehrlichia chaffeensis was first described in 1987. The disease occurs primarily in the southeastern and south central regions of the country and is primarily transmitted by the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum (Figure 6). Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) represents the second recognized ehrlichial infection of humans in the United States, and was first described in 1994. The name for the species that causes HGE has not been formally proposed, but this species is closely related or identical to the veterinary pathogens Ehrlichia equi and Ehrlichia phagocytophila. HGE is transmitted by the black-legged tick (Ixodes scapularis) and the western black-legged tick (Ixodes pacificus) in the United States (Figure 7).

Symptoms of ehrlichiosis are somewhat similar to Rocky Mountain spotted fever. For more information, visit the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's page on ehrlichiosis.

Protecting Yourself From Ticks

- Stay on wide clear paths and roads when possible. Avoid overgrown weedy areas where ticks are often found.

- When practical, layer your clothing. Tuck your pant legs into your socks and your shirt tail into your pants. Wearing light-colored clothing makes ticks easier to see.

- Most commercial insect repellents are effective against ticks (see Insect Repellent Products). Liberally apply one of these to exposed areas of your body and to your clothing.

- When camping, try to select an area that is not heavily infested with ticks. You can check for ticks by dragging a piece of white flannel cloth or clothing over the grass and shrubs and then examining it for ticks.

- When you have been in a tick-infested area (even a well-maintained lawn), examine your clothing and body at least twice each day. Frequent self-inspection lessens the chance of a tick having enough time to attach. A tick must be attached at least six hours in order to transmit disease organisms causing Rocky Mountain spotted fever and more than 24 hours to transmit Lyme disease. Therefore, the longer that a tick is attached, the greater the chances are that the disease-causing germs will be transmitted.

- Blood test for tick-borne diseases rely on detecting antibodies which take several weeks to reach detectable levels. Other signs & symptoms (as noted above) are more likely to develop before you can get an accurate test done.

Removing Ticks

- The risk of infection with tick-transmitted disease organisms can be greatly reduced by inspecting yourself frequently for ticks and promptly removing any that have attached. Applying petroleum jelly or cleaning fluid or holding a burning cigarette near an attached tick will not cause it to dislodge. Such “home remedies” often irritate the skin and kill the tick, making it difficult to remove it intact.

- Use a piece of folded tissue paper or use tweezers to remove the tick. Disease organisms carried by an engorged tick may penetrate even microscopic breaks in your skin. Grasp the body of the attached tick firmly as close as possible to your skin. Then, without twisting or jerking the tick, pull directly away from the point of attachment, increasing the force gradually until the tick is pulled free.

- If the tick’s mouthparts break off in the skin, use a sterilized needle to remove them as you would a splinter.

- Wash the bite area with soap and water and apply an antiseptic such as alcohol.

- Wash your hands thoroughly with soap and water after removing the tick.

- Mark the date of the tick bite on a calendar. If you develop any symptoms of Rocky Mountain spotted fever or Lyme disease, you will be able to tell your physician when you were bitten.

- Save the tick by preserving it in rubbing alcohol. If you cannot identify it using the pictures in this publication, take it to your county Cooperative Extension center.

Ticks and Pets

Pets may transport ticks into the family living area, so inspect them frequently for ticks. Remove attached ticks from pets using the same procedures described for people. Control ticks on pets using products recommended by your veterinarian. Contact your county Cooperative Extension center for advice on pesticides or you can check the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Controlling Ticks Around Your Home and in Public Areas

- As mentioned earlier, ticks spend time off their hosts down in the moist soil or on tall grass and weeds. Keep these areas mowed / trimmed to cut down on tick questing sites and to discourage rodents and other potential tick hosts from becoming established.

- Reduce exposure to ticks by removing the leaf litter layer around and under picnic tables, in campsites, and along hiking trails.

- Severe tick infestations can be controlled effectively with pesticides. Uniform and thorough (not excessive) application is critical to achieving adequate control. If a liquid formulation is used, the ground cover in tick-infested areas should be wetted thoroughly to the soil surface. This is particularly important during dry periods when the soil surface may bind up pesticides. Spraying a few hours after rainfall or after watering your lawn will help chemical penetrate better. These applications are often best done using a hose-end sprayer If you use a granular pesticides, apply it before rainfall or else water the area after applying the granules to ensure that the pesticide is released. Keep children and pets out of treated areas until the chemical has dried. Contact your county Cooperative Extension center for advice on which pesticides to use against ticks or check the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Publication date: June 14, 2018

Reviewed/Revised: June 22, 2019

AG-428

The use of brand names in this publication does not imply endorsement by NC State University or N.C. A&T State University of the products or services named nor discrimination against similar products or services not mentioned.

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.