Introduction

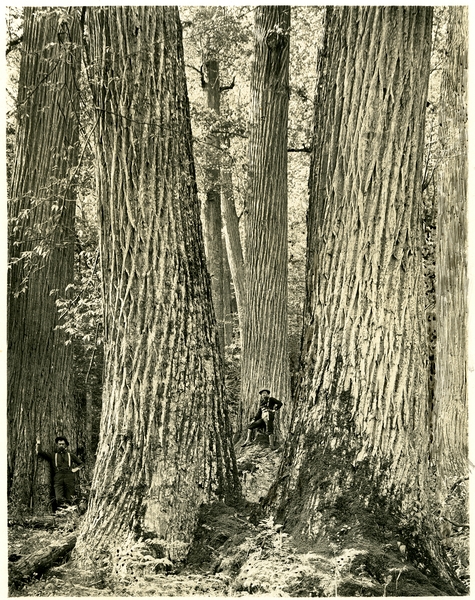

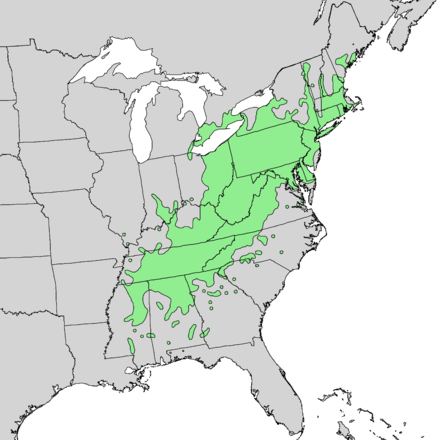

American chestnut (Castanea dentata) once dominated portions of eastern North American forests and were considered the "redwoods of the East" (Fig 1.). Their historical range stretched across 29 states, extending into the southeastern deciduous forests of Canada (Fig. 2). With its strong, rot-resistant wood and abundant annual crop of nutrient-dense chestnuts, the American chestnut was once an invaluable hardwood for humans and wildlife before the chestnut blight decimated its populations in the early 1900s.

Chestnut blight is a canker disease caused by a fungal pathogen in East Asia. It was first detected in New York in 1920; however, the initial introduction could have occurred as early as 1876 with the first imports of Chinese chestnut (Castanea mollissima) and Japanese chestnut (Castanea crenata) nursery stock (Anagnostakis, 2000). By 1950, the blight had spread through much of its range, infecting more than 80% of mature American chestnut trees (Henderson, 2023). Today, American chestnut is considered functionally extinct in the forests it once dominated.

Causal Agent

A non-native fungus, Cryphonectria parasitica (formerly Endothia parasitica), is the pathogen that causes chestnut blight. In its native range of East Asia, the fungus infects Chinese chestnut and Japanese chestnut; however, both species have coevolved with the pathogen and have developed resistance to its devastating effects (Jeffries, 2014). Chinese and Japanese chestnuts that do succumb to the pathogen are typically unhealthy trees already stressed from other environmental factors.

Host Plants

The fungal pathogen that causes chestnut blight can infect a wide range of host tree species in the Family Fagaceae; however, species in the genus Castanea, mainly the American chestnut and the European chestnut (Castanea sativa), are the most vulnerable to infection. Secondary hosts include oaks (Quercus spp.), maples (Acer spp.), European hornbeam (Carpinus betulus), shagbark hickory (Carya ovata), and American chinkapin (Castanea pumila). The threat to the persistence of these secondary hosts is minor (Rigling, 2017).

Disease Cycle

The pathogen spreads via wind-borne fungal spores or are vectored by birds and mammals (Scharf, 2011). When young, American chestnut trees has impenetrable bark to the spores, but as they mature, the bark naturally develops deep vertical furrows or fissures (Fig. 3). Spores invade injuries or these furrows in the bark, leading to the development of cankers (Fig. 4). In most cases, these cankers kill the cambium, eventually girdle the tree, and kill trees within three years of initial infection (Jeffries, 2014).

Because the pathogen does not kill the underground root system, chestnut blight infection is not always an immediate death sentence. In these instances, the root system continues to produce sprouts. However, as the sprouts age, furrows in the bark develop, allowing the pathogen to enter and reinfect the new trees. Trees are killed before reaching reproductive maturity (Henderson, 2023), reducing a once prominent canopy tree to an understory shrub. Although this cycle of death and rebirth has prevented the species from numerical extinction, American chestnut has been considered functionally extinct for decades.

Signs and Symptoms

On infected younger trees that have not yet developed deep furrows in the bark, cankers may appear sunken or swollen and are orange in color (Fig. 5). Stems may also bear numerous yellow to orange or reddish-brown blister-like pustules (Fig. 6). Within only a few weeks, cankers cause girdling and subsequent flagging, a condition where branches and leaves wilt, turn brown, and die. Sprouts may also be present directly below cankers.

In older trees, orange-colored, longitudinal cracks (Fig. 7) may be present in the bark, although most of the canker is hidden underneath the bark. Swelling and loose bark (Fig. 8) are typical where cankers have developed. Flagging is also another common symptom of an infected tree. Trees that have not yet succumbed to the disease will appear as stumps or standing dead trees with root collar sprouts, multiple sprouts emerging from the base of the trunk (Fig. 9).

Is There Hope for the American Chestnut?

Restoring the ‘Redwoods of the East’ across their historical range is an arduous journey that will likely take decades. Because the fungal spores that cause the disease are wind-dispersed and can be harbored on many hosts, eradicating the pathogen is unfeasible. Moreover, discovering that the American chestnut is also vulnerable to a root disease caused by the fungal pathogen Phytophthora cinnamomi, presents another hurdle for their recovery (Gustafson, 2022). Despite this, we are in a time of great optimism for restoring a once prominent feature across eastern deciduous forests. Researchers, the US Forest Service, non-profit organizations like the American Chestnut Foundation, and volunteers have made great efforts to prevent the complete loss of the species. Breeding and genetic engineering of blight-resistant American chestnut trees holds much promise.

In 1989, the American Chestnut Foundation (TACF) established a breeding program at the Wagner Research Farm in Meadowview, Virginia. Chinese chestnut, which are resistant to the blight, were crossed with American chestnut to produce blight-resistant trees that are 50% American and 50% Chinese. These hybrids were then repeatedly backcrossed to American chestnut and screened at each step to produce a blight-resistant American chestnut that retained no distinguishable physical characteristics of Chinese chestnut. The resulting B3F3 generation was backcrossed with American chestnut three times, inheriting roughly 94% of their genome from American chestnut but maintaining blight resistance genes of Chinese chestnut. TACF continues to breed beyond the B3F3 generation but considers them suitable for the start of the reintroduction process.

In conjunction with the American Chestnut Foundation, the American Chestnut Research and Restoration Project at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY ESF) produced 'Darling 58', a genetically engineered American chestnut with blight tolerance. Researchers insert a gene from wheat called oxalate oxidase (OxO), producing American chestnut trees that retain nearly 100% of their natural genes but can coexist with the pathogen. The OxO gene prevents the development of cankers by detoxifying the acid produced by the pathogen.

As a part of the development of reintroduction and management strategies, several experimental outplantings are being hosted on both public and private lands to monitor growth and assess response to silviculture treatments. Aside from blight resistance, B3F3 and 'Darling 58' have shown no significant ecological differences compared to wild American chestnut. Researchers with TACF and the SUNY ESF have proposed that these blight-resistant American chestnut trees can cross-pollinate with wild American chestnuts, spreading blight resistance to subsequent generations. They are awaiting USDA, EPA, and FDA approval to plant these genetically engineered American chestnut trees in our forests. If approved, it will be the first genetically engineered forest tree planted in the wild in North America.

Other Resources

The American Chestnut Foundation

Anagnostakis, S.L. 2000. Revitalization of the Majestic Chestnut: Chestnut Blight Disease. APSnet Features. Online. doi: 10.1094/APSnetFeature-2000-1200

Carlson, E., Stewart, K., Baier, K., McGuigan, L., and Powell W. 2021. Pathogen-induced expression of a blight tolerance transgene in American chestnut. Mol Plant Pathol. 2022 Mar;23(3):370-382. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13165. Epub 2021 Nov 28. PMID: 34841616; PMCID: PMC8828690.

Gustafson, E. J., Miranda, B. R., Dreaden, T. J., Pinchot, C. C., & Jacobs, D. F. (2022). Beyond blight: Phytophthora root rot under climate change limits populations of reintroduced American chestnut. Ecosphere (Washington, D.C), 13(2), n/a.

Henderson, A. F., Santoro, J. A., & Kremer, P. 2023. Impacts of spatial scale and resolution on species distribution models of American chestnut (Castanea dentata) in Pennsylvania, USA. Forest Ecology and Management, 529, 120741.

Jeffries, S.B., and T.R. Wentworth. 2014. Exploring Southern Appalachian Forests: An Ecological Guide to 30 Great Hikes in the Carolinas, Georgia, Tennessee, and Virginia. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC, USA. (p):257-258

Publication date: April 27, 2023

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.