A community food garden may begin with a neighborhood leader’s idea, a casual conversation over coffee, or a formal proposal from the parks department. No matter who sows the seed, community garden organizers face the same challenge—how to transform an appealing vision into a thriving garden. North Carolina Community Garden Partners (NCCGP), The American Community Gardening Association (ACGA), and other experienced garden organizers suggest a step-by-step approach.

Form a Garden Team

Creating a community food garden is like a barn raising: don’t try to do everything yourself. Starting and sustaining a community garden requires a committed group of people working together. Forming this group is the first step in creating a garden. For convenience, we will call this group the garden team.

Organizing a garden team isn’t difficult. Usually, two or three people are already involved right from the start, informally discussing the potential for a garden. Recruit others who are interested in community food gardening, particularly people with skills, experience, and perspectives that can help the effort.

Keep the size of the team small and manageable at first, about a half-dozen members, to make collaborative work and communication easier. As the project progresses, expand the group to include resource people, highly motivated volunteers, and most importantly, potential gardeners.

Research Community Gardening

Even as the garden team is forming, learn as much as possible about community food gardening. Contact local community gardeners, and take a group to visit them and their gardens. Take pictures and ask lots of questions: What do they like about their garden design? What would they do differently? Community gardening programs outside your area are accessible for “virtual” visits, thanks to the Internet. Research city zoning and land use policies to understand how these policies could affect the practices and long-term sustainability of the garden. See the References section for suggested resources.

Choices and Decisions

Once garden team members are sure that a community food garden is the right choice, project planning can begin. See the list of Garden Questions below for discussion points. These questions do not have a single right answer, although there may be strong opinions. Actively seek common ground within the team, and try not to let differences in viewpoint derail the garden’s progress.

|

GARDEN QUESTIONS

|

A helpful tool for establishing common ground is consensus-based decision-making, which includes actively seeking ideas everyone can support, rather than relying on “majority rules” voting to make choices. Consensus building often requires more time and flexibility and the ability to listen respectfully to different points of view, but it results in more creative solutions and a stronger, more unified team. We encourage community gardeners to learn more about participatory decision-making by reviewing guides such as Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision-Making by Sam Kaner.

Write a Summary Description

When the garden team is reasonably clear about how they envision the garden, write down a brief summary of key ideas. Keep this summary close at hand, and update and improve the text as the project progresses.

Organize and Assign Tasks

After team members have reached consensus, decide how to divide responsibilities and tasks among the team. A simple, informal organizational structure may work best early in the project. For many small-to-medium-sized gardens, this informal structure remains effective even after the garden is well established. Set target deadlines for completing tasks. Even if the team can’t meet every deadline, a timeline is a powerful incentive and organizational tool.

Small is Beautiful

Organize your garden project as a series of bite-sized steps rather than trying to create a huge, perfect community food garden from day one. Working in phases provides better, quicker, and more sustainable results than trying to do an overly ambitious project all at once. For instance, consider beginning with plots for five or six enthusiastic gardeners and a single hose line. The garden can expand as the gardeners’ success attracts more interest.

Spread the Word

With the garden’s written project summary and proposed timeline in hand, reach out to the broader community. Organize community meetings and presentations for potential gardeners, neighborhood associations, public agency representatives, possible funders and sponsors, and others who are curious about community gardening. Focus on potential host neighborhoods and sponsoring organizations. Have answers ready for practical questions such as, “How do I get a plot?” and “When can I start gardening?” Long before you have even chosen a site people will want answers to these questions.

Finding a Sponsor

For many new community garden groups, finding a sponsor is a high priority, and with good reason. A sponsor is an organization or individual that helps to set up and manage the garden. This person or entity may lend financial support to help pay for tools, supplies, fencing, land preparation, water lines, and insurance. In some cases, the sponsor provides the land for a garden site, at no cost to the gardeners, and funds a garden coordinator or other support staff.

A sponsor may be a public or private entity. Parks and recreation department community garden programs are good examples of public sponsorship. Faith-based groups, such as churches, may sponsor gardens on church property or work to support community food gardens at sites throughout their areas. Other sponsors might include land trusts, food banks, slow food groups, and other non-profit organizations. Organizations and agencies with an interest in community gardening are often on the lookout for sponsorship opportunities, especially projects with strong community support and a well thought-out plan.

Sponsors sometimes set strict conditions or insist on making all garden decisions. For this reason, some grass-roots community garden groups decline sponsorship, preferring the freedom to make their own choices to the security of having a sponsor.

The benefits of working with a sponsor, however, often outweigh potential drawbacks. Just be aware that the garden team, the sponsor, and eventually the gardeners must all be able to work together effectively.

|

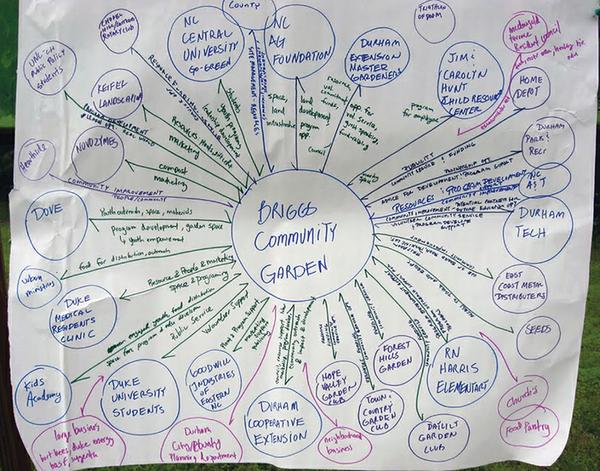

Potential Community Garden Sponsors

Many other possibilities exist, including non-profit organizations and private businesses. |

Community Garden Support Programs

Community garden support programs provide advice and assist community gardens, particularly during their start-up phase. Though they do not sponsor gardens, they can act as a bridge between a new garden and potential sponsors. These programs are now active in an increasing number of US cities, often staffed by AmeriCorps, VISTA, and Food Corps volunteers.

Don Boekelheide CC BY 4.0

School Gardens and Community Gardening

First Lady Michelle Obama's White House garden and concern for the health and nutrition of children and youth have helped reawaken national interest in youth gardening at pre-, elementary, middle, and high schools.

School gardens are specialized community gardens, so much of the information in this manual will be useful in setting up a school garden. However, we also recommend seeking out additional resources that directly address school gardening, particularly focusing on curriculum and lesson planning, which is not a concern for most community gardens in non-educational settings.

Working with a school adds additional layers of complexity and challenge to setting up and managing a garden. As with any community garden, the wider school community, including students, parents, teachers, administrators, and maintenance workers, must support and take ownership of the garden. Once there is buy-in, many approaches to gardening can work in a school setting.

Students, the most important stakeholders in a school garden, are sometimes excluded from planning the garden, despite the wonderful learning opportunities inherent in the early phases of garden planning. Identify age-appropriate activities throughout the process to involve students from the beginning.

Simply having an inspiring idea is not enough to create a successful school garden. School garden organizers must forge cooperative partnerships with the principal and staff, as well as the teachers, students, and parents. They must also work with custodians, and sometimes hired landscape contractors, to ensure the garden is being managed in a way that works for everyone. In addition, school gardens also must satisfy requirements of the school's governing body and respond to interest and concern from neighbors and funding agencies.

If a suitable site is available near a school, combining a school and community garden has many benefits, including the possibility that community gardeners can tend and harvest a food garden over the summer when school is out. One relatively easy option in a plot garden is to reserve a plot or two for a nearby school.

Here are a few practical suggestions for creating a school garden:

- In the piedmont, coastal plain, and warmer mountain valleys, plant cool season varieties (lettuce, broccoli, root crops) in August as part of back-to-school.

- As the garden grows, include it in science lessons.

- Make compost from leaf drop in between Thanksgiving and the winter break.

- Plant lettuce, radishes, and other cool season plants in March.

- Older children can start their own seedlings indoors using lights and even take warm season crops, such as tomatoes and peppers, home for their family gardens when school lets out for summer.

|

Visit the following resources for more information on youth gardening: |

Lucy Bradley CC BY-NC 4.0

Don Boekelheide CC BY 4.0

Don Boekelheide CC BY 4.0

Lucy Bradley CC BY-NC 4.0

Publication date: Aug. 10, 2017

AG-806

Other Publications in Collard Greens and Common Ground: A North Carolina Community Food Gardening Handbook

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.