Warm-season annual forages, such as crabgrass (Digitaria spp.), can be a key component for year-round forage production systems in North Carolina. Although some people classify crabgrass as a weed, it can be a very useful forage crop. This publication discusses crabgrass as a forage and summarizes research findings on productivity and nitrogen fertilization in the piedmont and coastal plain of North Carolina (Sosinski et al., 2022).

General Information

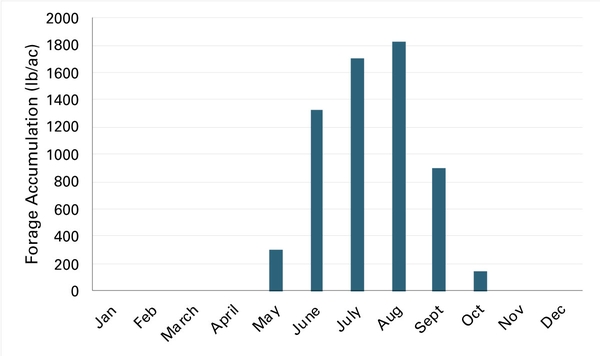

Crabgrass is a warm-season annual grass with potential to complement the cool season–based forage systems in North Carolina by providing forage during the summer months (Figure 1). Managers of land and livestock have typically recognized crabgrass as a ubiquitous and reoccurring species in grazing- and hay-land. In some cases, crabgrass species have been deemed desirable as a primary or secondary (“fallback”) forage in pasture-based livestock systems (Figure 2); in other cases, it may be considered an undesirable weed interfering with the establishment of planted forages or row crops. Nonetheless, research efforts have brought to market several cultivars for crabgrass, such as Red River, Impact, and Quick-N-Big (Bouton et al., 2019).

Establishment and Management

Crabgrass will grow on almost any soil, but it grows best in well-drained, medium- to coarse-textured soils, such as sandy loam, sandy clay loam, and clay loam soils. The most common situation where crabgrass benefits forage programs is in places where it volunteers—that is, it establishes from the resident soil seed bank. This situation occurs mainly in weak or degraded pastures or hayfields where canopy cover of the desirable perennial forage species was reduced by adverse weather conditions or other stresses. Crabgrass will often “fill the gaps” in this situation, thus making a significant contribution of forage in years when such a field would otherwise produce much lower forage biomass. But relying on volunteer crabgrass to provide pure stands is risky due to erratic establishment.

Planting crabgrass can also be a highly appropriate land and forage management strategy, especially in fields where winter annual forages are planted on a prepared seedbed each autumn. This works well because the growing seasons of winter annuals and crabgrass are quite complementary. For example, ryegrass can be followed by crabgrass in an annual pasture—hence, a ryegrass-crabgrass system (Figure 3). By late August or early September, crabgrass growth declines, which coincides with the time to establish winter annuals.

Planting crabgrass can start around early May to a recommended depth of ¼ inch soil depth. Recommended planting rates are 8 to 10 pounds per acre if broadcasted or 5 to 7 pounds per acre if drilled. Planting too deep is usually an issue when establishing crabgrass, so broadcasting as the planting method is highly encouraged. More details about forage establishment in North Carolina can be found in Extension publication AG-266, Planting Guide for Forage Crops in North Carolina. Although using a target calendar date is very helpful as a starting reference, one should continuously check the weather (that is, rainfall and temperature) to target field activities for planting crabgrass. Crabgrass usually starts to germinate when soil temperatures reach 55°F to 58°F for two to five consecutive days. Adequate rainfall and soil moisture are of utmost importance for crabgrass, leading to wide variations in productivity (Bouton et al., 2019). Interestingly, adequate planting conditions for crabgrass in North Carolina are signaled by the time that dogwood trees (Cornus florida) are flowering.

When planting by early May, the first harvest event could occur as early as forty-five days after planting, assuming adequate weather conditions occur. Defoliation management, either clipping or grazing, should target a stubble height of 3 to 4 inches when pastures are rotationally stocked or the forage is harvested for hay. More details for management of the canopy height when pastures are rotationally stocked can be found in AG-939, Pasture Grazing Heights for Rotational Stocking. In North Carolina, it took about 21 days in July-August and about 30 days in August-September timeframes for crabgrass to recover and be ready (about 10 to 12 inches canopy height) for another defoliation event (Sosinski et al., 2022). The length of the growing season for crabgrass can vary, on average, from 60 to 120 days from early May to mid-September in North Carolina.

Forage Accumulation

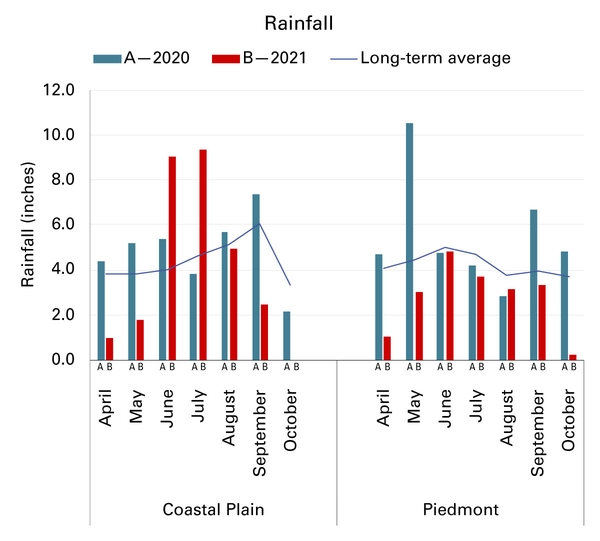

Field trials in North Carolina evaluated nitrogen fertilization rates using chemical fertilizer and poultry litter for two years in the piedmont and coastal plain and their effects on forage accumulation, nutritive value, and tissue-N concentration of crabgrass (Sosinski et al., 2022). The nitrogen fertilization rates ranged from 0 to 427 pounds per acre. The field season to measure crabgrass responses had four sampling events in the coastal plain (first and last clippings of the season were done in early July and early September, respectively) for the two years of experimentation; however, the length of the growing season was shorter in the piedmont in 2020, and overall crabgrass responses in this region were erratic during the two years of experimentation.

In 2020 in the piedmont, high cumulative rainfall in May (about 10 inches, which was more than double the long-term average for May; Figure 4) resulted in failed establishment of crabgrass. This required re-establishment of the plots, ultimately resulting in only two harvesting events that year. In contrast, lower rainfall (about 12 inches less than the long-term normal of 31 inches during the May through October timeframe) was deemed the limiting factor, resulting in lower forage accumulation in the piedmont in 2021 compared to the coastal plain. These events highlight the rainfall variability and the associated risk when relying solely on annual forages for pasture-based livestock systems. On average, the forage harvested at each sampling event was 0.7 tons per acre in the coastal plain and 0.4 tons per acre in the piedmont. Because grazing livestock require a consistent supply of forage to graze year-round, it is critical that land and livestock managers consider developing a perennial forage-based system first. The perennial component could then be complemented with annual forages planted on selected fields on the farm.

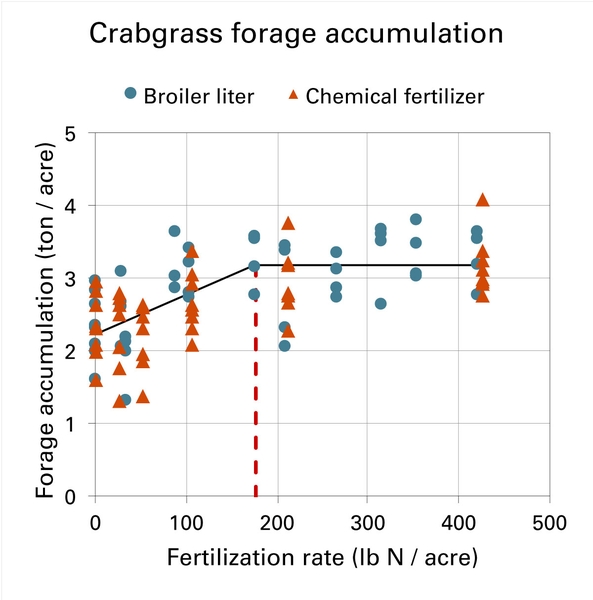

In the coastal plain, forage accumulation of crabgrass increased from 2 tons per acre with no addition of nitrogen fertilizer to 3.2 tons per acre at an agronomic optimum nitrogen rate of 177 pounds N per acre (Figure 5). There was no difference in forage accumulation of crabgrass between chemical fertilizer and poultry litter application rates when accounting for a plant-available N coefficient of 50% for the broiler poultry litter (Kulesza, 2022). In the piedmont, overall forage accumulation across nitrogen fertilization rates was ≤ 1.8 tons per acre. Greater forage accumulation values than those reported in this study have been reported for crabgrass in other states, especially south of North Carolina. Such responses are likely a function of different environmental conditions and longer growing seasons (McLaughlin et al., 2004).

The information in Figure 5 can be useful for establishing a nitrogen factor (N factor) for crabgrass. The N factor has been defined as pounds of nitrogen required per unit crop yield (Osmond et al., 2020). It is used for development of nutrient management plans in North Carolina. For example, dividing the agronomic nitrogen rate of 177 pounds N per acre (Figure 5) by the total seasonal herbage accumulation of 3.2 tons per acre, the N factor is 55. The establishment of N factors requires data from multiple site-years, hence the data obtained in this experiment provide a first assessment and guidance of what this factor would be after calibration.

Nutritive Value, Livestock Requirements, and Nitrate Concentration

Crude protein concentration values ranged from 12.6% to 15.4% across locations and years. Total digestible nutrient concentration (TDN) ranged from 59.6% to 65%. Using average values of 14% crude protein and 62% TDN, the TDN/CP ratio is 4. When forage TDN/CP ratio is less than 7, as in this case, providing supplemental feed is not justified because voluntary animal intake and animal performance due to supplementation are not expected (Moore and Kunkle, 1999). In other words, the nutritive value of the forage may be high enough to meet the nutritional demand of livestock.

Mature lactating beef cows (approximately 1,200-pound body weight) require 2.8 pounds of crude protein per day to maintain a body condition score of 5 and reproductive function (National Research Council, 1996). Considering crabgrass with average crude protein of 14% and intake of 2.3% body weight, crabgrass would provide 3.9 pounds of crude protein per day, more than satisfying the daily requirement. Even at the fertilization rate of 0 pounds N per acre in this trial, crabgrass with 12% CP would satisfy the daily requirement of the mature lactating cow. Similarly, considering an average TDN value of 62% for crabgrass and the daily requirement of the mature beef cow of 16.9 pounds TDN per day, crabgrass would also satisfy the daily requirement of the cow by providing 18 pounds TDN per day. Hence, crabgrass being the sole source of feed can meet the nutritional demands of the mature lactating beef cow while maintaining optimum performance.

Tissue nitrate concentration values across the experiment were below the toxic threshold (that is, ≤0.5%) for feeding livestock. Concentrations tended to be lower when poultry litter was the N source and during the late-season sampling events.

Summary and Conclusions

Crabgrass forage has potential to complement perennial-based forage systems in North Carolina and contribute high nutritive value forage for livestock. From two years of field trials (2020 and 2021), forage accumulation, number of harvest events, and length of the growing season were greater and more consistent in the coastal plain versus the piedmont.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time crabgrass responses have been reported in North Carolina. It is common to see crabgrass growing vigorously in the piedmont and coastal plain, but rainfall conditions in the piedmont were not conducive to optimum growth of crabgrass during the two years the trials were conducted.

Differences in crabgrass responses in the two regions were associated with variations in the rainfall pattern. Specifically in the piedmont, excess rainfall right after planting in 2020 resulted in a failed stand of crabgrass. In contrast, limited rainfall across the season in 2021 resulted in lower forage accumulation. If weather conditions and management are adequate, crabgrass grown in North Carolina will provide about 2 to 4 tons per acre of forage resulting from three to four harvest events of about 0.4 to 0.8 ton per acre for each harvest event, with crude protein values between 12% and 15% and total digestible nutrients at or greater than 60%, during a growing season varying from 60 to 100 days.

References

Bouton, J.H., Motes, B., Trammell, M.A., and Butler, T. 2019. “Registration of ‘Impact’ Crabgrass.” J. Environ. Qual. 13, 19–23. ↲

Kulesza, S. 2022. Nutrient Management in North Carolina. North Carolina State University. ↲

McLaughlin, M.R., Fairbrother, T.E., and Rowe, D.E. 2004. “Forage Yield and Nutritive Uptake of Warm-Season Grasses in a Swine Effluent Spray Field.” Agron. J. 96:1516–1522. ↲

Moore, J.E., Brant, M.H., Kunkle, W.E., and Hopkins, D.I. 1999. “Effects of Supplementation on Voluntary Forage Intake, Diet Digestibility, and Animal Performance.” J. Anim. Sci. ↲

National Research Council (NRC). 1996. Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle. 7th ed. National Academies Press. ↲

Osmond, D. Gatiboni, L., Kulesza, S., Austin, R., and Crouse D. 2020. North Carolina Realistic Yield Expectations and Nitrogen Fertilizer Decision. AG-878. ↲

Sosinski, S., Castillo, M.S., Kulesza, S., and Leon R. 2022. “Poultry Litter and Nitrogen Fertilizer Effects on Productivity and Nutritive Value of Crabgrass.” Crop Sci. ↲

Publication date: Dec. 5, 2024

AG-976

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.