Introduction

Over time, consumers have shown consistency in preferring sustainable options, reflecting their attitudes toward environmentally friendly products. Terms like “environmentally friendly,” “green,” and “sustainable” are often used interchangeably for products commonly associated with qualities such as resource conservation potential, low energy consumption, protection of public health, and reduced environmental impact throughout their life cycle (Cooper-Ordoñez et al. 2018; Bhardwaj et al. 2020). A growing body of literature indicates that the preference among consumers for environmentally friendly products over conventional ones is increasing. Specific preferences, however, particularly in the context of sustainable floriculture, remained relatively underexplored in research until recent decades.

In the past, research specific to the floriculture industry was limited due to challenges in defining product categories, gathering data, and securing adequate funding for research dissemination (Behe 1993). It wasn't until the late 2000s that increased research efforts to understand consumers’ sustainability preferences began to be addressed in the context of sustainable floriculture. Although there is limited research, this review explores overarching trends shaped by factors influencing public perceptions of sustainability. The primary focus will be an in-depth exploration of trends in sustainable floriculture between the late 2000s and the 2020s.

It is essential to acknowledge that consumers are diverse, each influenced by an array of factors when it comes to receptiveness toward environmentally friendly products. Research has identified various aspects, including demographics, knowledge, values, attitudes, and behavior, which can significantly shape consumer preferences (Laroche et al. 2001; Behe et al. 2010; Yue et al. 2016; Etheridge et al. 2023). Examining each of these aspects independently may lead to a better understanding of consumers’ decision-making processes and more accurate predictions. While we emphasize the significance of recognizing the uniqueness of consumer preferences, we also recognize the value in exploring common themes and shared attitudes found in the existing literature. By doing so, we can gain insights into how consumer attitudes have evolved, providing a broader view of sustainable consumerism’s progression over time.

1990s: Early Sustainability Initiatives and Challenges

During the 1990s, heightened environmental concerns drew public attention. Key events, such as the discovery of the ozone layer hole, the environmental impact of the Gulf Wars, and consistent emphasis on environmental issues in academic literature and popular press articles, potentially shaped consumer preferences during that period (Roberts 1996). For example, the Time article "The Greening of America" (Gibbs 1990) discussed how Americans are considering environmental business practices, and articles highlighting the Earth Summit in Rio appeared in The New York Times (Friedman 1992; Revkin 1992).

Businesses, corporations, institutions, and governmental and nongovernmental entities, facing public and political pressure, started adopting more sustainable practices, such as recycling, waste reduction, and energy conservation initiatives (Roberts 1996; Swarbrooke 1999). Green products such as recycled paper products and compact fluorescent lamps (CFLs) surged 13.4% from 1989 to 1991 (Roberts 1996). This growth was accompanied by a quadrupled increase in advertising of environmentally friendly products during this period (Roberts 1996). However, marketers and advertisers struggled to effectively communicate the reasons behind these initiatives to consumers or provide adequate guidance to manufacturers on what consumers with pro-environmental behaviors desired (Bhate 2005).

In 1990, SC Johnson conducted interviews with 1,400 U.S. consumers, in which 39 percent stated that they were confused as to what is good and bad for the environment. Although awareness improved by the mid-1990s, with 50% of respondents claiming that they knew a lot or a fair amount about environmental issues and problems, education on sustainability remained limited for both consumers and companies (SC Johnson 2011). Despite the heightened awareness and increased advertising of “green” products in response, consumers hesitated to opt for these products over conventional ones, due mainly to concerns about price, performance, and a lack of knowledge about the products (Roberts 1996).

Though consumers expressed a desire for eco-friendly options, factors such as limited accessibility, affordability, and limited knowledge hindered the widespread consumer adoption of pro-environmental behaviors. As a result, the demand for floral products with sustainable attributes remained modest compared to more recently.

2000s: Organic Flowers Boom

The organics movement in the United States originated from the public’s growing concern about pesticide usage and embrace of “back to nature” ideology of the 1960s. These changes in consumer attitudes were spurred by whistleblowers, particularly Rachel Carson, the author of Silent Spring. Carson’s investigations found that pesticidal chemicals have a harmful effect on the environment. Such research contributed to the establishment of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1970. The Organic Trade Association, a membership-based business association for organic agriculture and products in the U.S., still cites as its original goal “to eliminate harmful pesticides from the food supply.”

The introduction of “certified organic” labeling by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) in 2002, indicating that a product was at least 95% organically produced, led to an increase in organic flower sales. By 2005, certified organic flower sales in the United States totaled $16 million, marking a 700% growth in sales from 2003 (Sung 2007).

Amidst a growing consumer inclination toward sustainable and eco-friendly products, the emergence of the Veriflora® Sustainably Grown program in 2005 further amplified consumer interest in organically grown flowers and potted plants. This third-party certification program emphasized cultivation methods that prioritize environmental preservation, including the implementation of organic practices at the farm level (Sung 2007; SCS Global Services 2023). By 2010, Veriflora certified flower sales reached $46 million (Vernabe 2012).

With the rise in popularity of organic flowers, growing preference among consumers for environmentally friendly products became evident. The introduction of certified organic labeling by the USDA and programs like Veriflora possibly drove the trend, clarifying visibility of organic flower choices for consumers. The surge in demand not only prompted major growers to seek organic certification, but consumers and retailers also started requesting certification from growers, with over 600 million stems being certified by the Veriflora program in 2007 alone (Sung 2007). In light of the increased demand and the active pursuit of sustainable certifications by both growers and retailers, the introduction of certified organic labeling and programs like Veriflora played a crucial role in consumer access to greener choices, marking a significant trend toward sustainable floral preferences. Mega retailers and florists increasingly began offering bouquets labeled “sustainable,” “fair trade,” and “organic” (Whelan 2009).

By 2001, Fairtrade International began certifying flowers to ensure fair global trade and promote sustainable practices, promising a lighter carbon footprint and reduced pesticide use. By 2007, U.S. growers had launched certified flowers into the marketplace. By 2010, according to a consumer insights report, 22% of general consumers were more likely to buy a product with the Fair Trade seal (Fair Trade USA 2023). It is important to note that this report refers to general certified products and doesn't specifically focus on floral products. Limited research is available regarding the fair-trade flower market in the United States. Nevertheless, anecdotal evidence and interviews with industry stakeholders suggest that this market exhibited slow growth during the early 2000s (Sung 2007; Raynolds 2012).

As public environmental concerns grew, there was a surge in exploring bioplastics as a sustainable alternative for governments and companies (Shen et al. 2009). Plant-based green materials gained global popularity due to their renewability and economic viability, prompting countries including the United States, Germany, and Japan to integrate these materials into their markets and invest in research on plant-based plastics (Berkesch 2005). Despite this trend, research on consumer preferences for bioplastics in floriculture was limited during this period.

2010s: Interest in Local, Organic, and Sustainable Pots

In the 2010s, the sustainable products market grew, as consumers became more informed about environmental practices across industries. This awareness led to increased consumer inquiries about green attributes and increased demand for companies to offer flowers produced through sustainable methods (Arizton 2018).

By this decade, consumer awareness about environmental issues significantly increased, with 73% of U.S. consumers reporting that they believed they possessed a fair amount of knowledge or extensive knowledge about environmental problems (SC Johnson 2011). In addition, 81% of global consumers surveyed in 2018 stated that they strongly believed that companies have a responsibility to contribute to environmental improvement (NIQ 2018). The increasing demand from consumers marked a turning point in which corporate sustainability became more of a necessity than a choice.

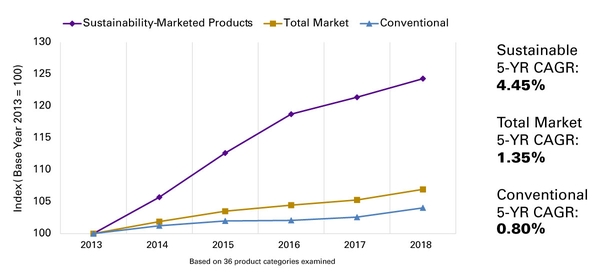

As sustainability claims became more common on consumer goods and consistently competed with traditional products, a clear shift toward eco-friendly choices in purchasing emerged during this period. By 2018, sustainability claims were made by 16.6% of consumer goods across 33 categories, representing a 2.3% increase from 2013 (Figure 1). These sustainable products outperformed their conventional counterparts, experiencing a growth rate 5.6 times faster and achieving 29% higher sales than in 2013 (Kronthal-Sacco and Whelan 2019).

In the floral industry, consumer preferences extended to plant containers, with a rising desire for sustainable material options as technological advances allowed for more choices. Consumers showed an increased interest in pots made from recycled materials, biopots, and compostable pots. This preference for sustainable pots suggests increased value placed on environmentally friendly packaging and materials (Yue et al. 2011). When asked about their relative interest, participants ranked local (60% interest), biopots (60% interest), compostable pots (50% interest) and recyclable pots (43% interest) as their top choices above organic (-22% interest, very uninterested), sustainable (13% interest), organic fertilizer (-1% interest, very uninterested), and efficient greenhouse (18% interest).

Another trend included growing consumer preference for locally sourced products. Some consumers defined flowers as local if they were produced within a 100-mile radius from where they purchased them, whereas others considered them local if they were produced in the same state (Arizton 2018). Between 2007 and 2012, flower farms selling domestic cut flowers increased by almost 20% (Beck 2015). By 2013, the “Slow Flowers” movement had emerged (Kizis 2023). This movement aimed to establish sustainable practices, support local economies, and reduce chemical use through purchasing domestically and ethically grown flowers. Research by Arizton found an inclination toward locally sourced products, with about half of consumers (51%) stating they would buy locally if given a choice (Arizton 2018). This preference is mirrored in a study looking at consumer interest toward different types of plants, which found that more than 60% of participants had more interest in local plants compared to conventional ones (Yue et al. 2011).

The appeal of locally grown flowers led to more support toward the local market. Across various retail outlets, 66% of supermarket retailers placed operational emphasis on sourcing products locally (Produce Marketing Association 2017). In addition, according to USDA data, between 2007 and 2017, farms reported that some or all of their acreage being devoted to cut flowers increased by 32%. This proactive response from industry firms further solidifies the notion that consumers were seeking locally sourced products.

Building on the momentum of the organic movement, sales of organic flowers in the U.S. increased by 12.5% to $450 million from 2016 to 2017. Although organic flowers didn't gain popularity as quickly as organic food and beverages, likely due to their higher production costs, consumers have shown a willingness to pay more for these products. Millennials, in particular, have voiced a strong inclination toward sustainability in their purchasing choices (Arizton 2018). Studies by Yue et al. (2016) revealed that among consumer preferences by this demographic group, reduced pesticide usage and organic cultivation methods emerged as top priorities. This suggests that reduced pesticide use and organic cultivation methods continued to hold weight in this period. Fair trade demand grew in this period, with a 16% increase in the general population's likelihood to purchase products bearing the Fair Trade seal between 2010 to 2020 (Fair Trade USA 2023). Despite this growth, fair trade had a smaller market share and was considered a lesser priority in the floriculture industry, with just under 10% of millennials ranking it as a primary consideration (Yue et al. 2016).

Even with the growing demand for organic and local products, there remained a lack of education and clear definitions surrounding "green" terms in this decade. For instance, a study investigating consumers' perceptions of the terms "local" and "organic" found that 23% of the participants believed "local" meant products were grown organically and without synthetic pesticide use, while 17% thought "local" was a characteristic of organic products (Campbell et al. 2014). This study suggested that consumers held inaccurate perceptions, mistaking "local" for “organic” and vice versa. In addition, a separate study found that 70% of consumers were unaware of the origin of flowers (Arizton 2018). This confusion shows the need for more effective consumer education and transparent labeling to help consumers make informed choices.

2020s: Sustained Preference for Locally Sourced Flowers and Sustainable Pots

The 2020s continues to witness a strong emphasis on sustainable products, influenced by shifts in generational market power. A 2021 survey from First Insight and the Wharton Baker Retailing Center found that there is more priority for sustainable products over brand names, with Generation Z placing the highest importance on sustainability, closely followed by Millennials and Gen X. In addition, in their 2019–2021 survey comparison, all generations indicated an increased willingness to spend at least 10% more on sustainable products between the two survey years (First Insight and the Wharton Baker Retailing Center 2021). It is clear that even with changing generational market dynamics, consumer demand continues to emphasize the importance of sustainable products.

In the 2020s, consumer preferences in the floral sector continued to favor locally sourced products and sustainable materials. This trend mirrored the inclination observed in the 2010s, showing a sustained consumer commitment to supporting local businesses and reducing environmental impacts. Consumer prioritization of locally sourced flowers persisted from the early 2010s through 2023. The 2021 annual survey by the National Gardening Association found 58% of respondents valued purchasing locally grown floral arrangements—a preference reaffirmed in consumer research by the 2023 Floral Marketing Fund (Whitinger, 2022; Etheredge et al. 2023). When given sustainable purchasing options, shoppers expressed greatest willingness to buy flowers from retailers with locally sourced flowers, with 61.7% of participants expressing a willingness to pay 10% or more for locally sourced flowers (Etheredge et al. 2023). The survey found that the consumers were least inclined to purchase from a retailer selling fair-trade sourced and organically grown flowers; their willingness to pay more was lowest for these two options, suggesting a preference for locally sourced flowers (Etheredge et al. 2023). Though additional characteristics like fair trade and organic cultivation remain relevant to consumers, there is a continued trend from the 2010s of more consumers preferring locally sourced flowers.

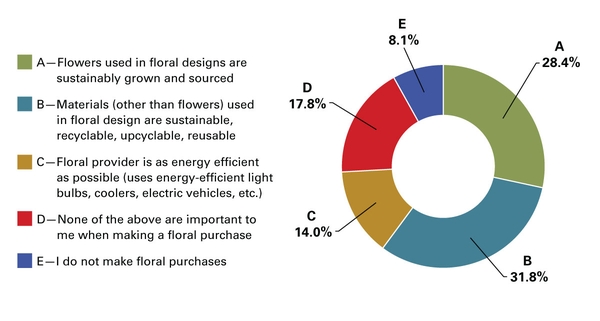

Survey participants were asked, “When deciding where to make a floral purchase, which of the following aspects of sustainability do you consider to be the most important for a retail floral provider to practice?” Respondents stated that their highest priority was for materials (other than flowers) used in floral design to be sustainable, recyclable, upcyclable, and reusable (31.8%); 28.4% wanted flowers used in floral designs to be sustainably grown and sourced; and 14.0% wanted the floral provider to be as energy-efficient as possible (Figure 2) (Etheredge et al. 2023). This aligns with a separate study examining consumer attitudes toward plastic alternatives, in which 72.8% of respondents expressed a willingness to pay more for products made from bioplastic compared to conventional plastic (Zwicker et al. 2020; Yue et al. 2010). These results collectively demonstrate consumers placing a growing value upon recyclable, reusable, and environmentally friendly materials.

However, misconceptions continued among consumers. A 2020 survey revealed that over half of the participants (58%) lacked a clear understanding of what defined bio-based plastic (Zwicker et al. 2020). Although emphasis on sustainable materials has grown, it remains crucial to provide education about sustainable materials for consumers to make informed decisions.

A recent survey found that the horticultural industry has been slow to adopt sustainable materials, including biodegradable containers, with growers expressing skepticism about their efficiency and benefits (Harris et al. 2020). Consumers, too, have misconceptions about sustainable terms and materials. Although technology broadens information access, it also brings the challenge of ensuring that accurate information reaches a wide audience and, as a result, can influence the adoption of these products. In order for the sustainable floriculture sector to leverage the influence of technology and thrive, it is essential to establish a strong online presence, especially in e-commerce platforms, and to ensure that accurate information is provided to both industry stakeholders and consumers.

As we observe the growth in consumer demand for environmentally friendly options, it becomes evident that these trends toward sustainability are not merely fads. As education, certifications, and accessibility to sustainable products grew over time, so did purchases of these eco-friendly items. While certain aspects of sustainable consumerism may fluctuate, the broader pattern indicates a growing connection between consumers and environmental concerns. The collective shift among generations toward sustainability suggests this trend will become further ingrained in the values and expectations of future generations, strengthened by a stronger foundation of knowledge and resources.

Conclusion

Consumer-perceived value of several sustainable practices in the floral industry has increased steadily since the early 2000s. Although limited, research explains why despite growing environmental concerns, consumers in the 1990s were reluctant to adopt sustainable products. However, the organic boom in the 2000s launched a pattern of increasing perceived value and demand for sustainable products among consumers that has continued into subsequent decades. The 2010s saw increased demand for sustainable, locally sourced, and organic products. In the 2020s, demand for locally sourced commodities continued to increase, reflecting a sustained commitment by consumers to support local businesses.

Businesses aiming to navigate the sustainable market successfully must understand the history and evolution of consumer trends. For instance, the organics movement in the United States was born out of concerns about pesticide usage and its environmental impact; this movement emerged in the 1960s, driven by figures like Rachel Carson. The significance of this historical context becomes more evident when we consider the organic boom that occurred in the 2000s. During this period, the USDA introduced the organic label, allowing for easy identification of organic products. The rise in sales by consumers in response to organic labeling emphasized the value placed on this particular attribute within products. Applying this kind of labeling to sustainable certification may provide clarity for consumer purchasing decisions.

By learning from the past, businesses can anticipate consumer responses and adopt strategies that appeal to consumers. Branching off the organic boom, businesses can emphasize sustainable and verifiable certifications. Currently, with the ongoing demand for locally sourced and sustainable pots, businesses can collaborate with local manufacturers, prioritize sustainable materials, and address misconceptions about these alternatives. By forming partnerships with local manufacturers and sourcing materials sustainably, companies can capitalize on the growing demand for products that reduce carbon footprints and have environmentally friendly impacts.

The rise of digital platforms and widespread adoption of e-commerce have been key in the influence of the sustainable market. Online visibility of product information has rapidly increased knowledge of and access to sustainable products. E-commerce is expected to continue boosting revenue for florists, with forecasts predicting a compound annual growth rate of about 2.8% for the next five years, linked to the surge in e-commerce sales (Rose 2023). Online communications can conveniently connect consumers to greener product alternatives on a wider scale. However, while digital platforms rapidly increase product information awareness and can be beneficial in the sustainable market, misinformation remains a challenge.

In summary, this report offers a comprehensive analysis of sustainable consumer behavior within the floriculture industry spanning from the 1990s to the 2020s, with context of perceptions from the 1950s and 1960s. With sustainability gaining more importance in the market, businesses need to adapt. Understanding the past, analyzing changing trends, and acknowledging external factors like technology enable businesses to deliver what consumers value. Ultimately, integrating historical context with emerging consumer trends provides a critical framework for businesses to anticipate future market shifts and develop strategic approaches that align with the increasing demand for sustainable products within the floriculture industry.

References

Arizton. 2018. U.S. Floral Gifting Market. Arizton Advisory and Intelligence. ↲

Beck, M. A. 2015. “Slow Flowers’ Movement Pushes Local, US-Grown Cut Flowers.” WHYY. ↲

Behe, B. K. 1993. “Floral Marketing and Consumer Research.” HortScience 28 (1): 11–14. ↲

Behe, B. K., B. Campbell, J. Dennis, C. Hall, R. Lopez, and C. Yue. 2010. “Gardening Consumer Segments Vary in Ecopractices.” HortScience 45 (10): 1475–1479. ↲

Berkesch, S. 2005. Biodegradable Polymers: A Rebirth of Plastic. Michigan State University. ↲

Bhardwaj, A., A. Garg, S. Ram, Y. Gajpal, and C. Zheng. 2020. “Research Trends in Green Product for Environment: A Bibliometric Perspective.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (22): 8469. ↲

Bhate, S. 2005. “An Examination of the Relative Roles Played by Consumer Behaviour Settings and Levels of Involvement in Determining Environmental Behaviour.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 12 (6): 419–429. ↲

Campbell, B. L., H. Khachatryan, B. K. Behe, J. Dennis, and C. Hall. 2014. “U.S. and Canadian Consumer Perception of Local and Organic Terminology.” International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 17 (2): 21–40. ↲

Cooper-Ordoñez, R. E., A. Altimiras-Martin, and W. L. Filho. 2018. "Environmental Friendly Products and Sustainable Development." In Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education. ↲

Etheredge, C. L., J. DelPrince, and T. M. Waliczek. 2023. U.S. Consumer Perceptions and Willingness to Pay for Sustainable Environmental Practices in the Floral Industry. Floral Marketing Fund. ↲

Fair Trade USA. 2023. Consumer Insights Report. ↲

First Insight and Wharton Baker Retailing Center. 2021. The State of Consumer Spending: Gen Z Influencing All Generations to Make Sustainability-First Purchasing Decisions. First Insight, Inc. ↲

Friedman, Thomas L. 1992. “At the Earth Summit, a Call to Action.” New York Times, June 13. ↲

Gibbs, Nancy. 1990. “The Greening of America.” Time, April 16. ↲

Harris, B. A., W. J. Florkowski, and S. V. Pennisi. 2020. “Horticulture Industry Adoption of Biodegradable Containers.” HortTechnology 30 (3): 372–384. ↲

Kizis, D. 2023. "There’s Slow Food, Slow Travel, and Slow Fashion—But Have You Heard of Slow Flowers? Here’s What to Know About the Trend." Sunset (website). ↲

Kronthal-Sacco, R., and T. Whelan. 2019. Sustainable Share Index™: Research on IRI Purchasing Data (2013–2018). NYU Stern. ↲

Laroche, M., J. Bergeron, and G. Barbaro‐Forleo. 2001. “Targeting Consumers Who Are Willing to Pay More for Environmentally Friendly Products.” Journal of Consumer Marketing 18 (6): 503–520. ↲

NIQ. 2018. "Global Consumers Seek Companies That Care About Environmental Issues." ↲

Produce Marketing Association. 2017. Trends in Mass-Market Floral. ↲

Revkin, Andrew C. 1992. “Nations Start to Sign Earth Pact.” New York Times, June 5. ↲

Raynolds, L. T. 2012. "Fair Trade Flowers: Global Certification, Environmental Sustainability, and Labor Standards." Rural Sociology 77 (4): 493–519. ↲

Roberts, J. A. 1996. "Green Consumers in the 1990s: Profile and Implications for Advertising." Journal of Business Research 36 (3): 217–231. ↲

Rose, A. 2023. Florists in the US (Industry Report No. 45311). IBISWorld. ↲

SC Johnson. 2011. The Environment: Public Attitudes and Individual Behavior—A Twenty-Year Evolution. GfK Roper Consulting. ↲

SCS Global Services. 2023. Veriflora® Sustainably Grown. ↲

Shen, L., J. Haufe, and M. K. Patel. 2009. Product Overview and Market Projection of Emerging Bio-Based Plastics. Copernicus Institute for Sustainable Development and Innovation. ↲

Sung, A. 2007. "Roses are Green." Supermarket News. ↲

Swarbrooke, J. 1999. Sustainable Tourism Management (1st ed.). CABI. ↲

Vernabe, J. 2012. "California Based Flower Farm Grows Market for Organic Flowers One Bouquet at a Time." Seedstock. ↲

Whelan, C. 2009. "Blooms Away: The Real Price of Flowers." Scientific American online, February 12. ↲

Whitinger, D. 2022. “2021 National Gardening Survey.” National Gardening Association. ↲

Yue, C., J. H. Dennis, B. K. Behe, C. R. Hall, B. L. Campbell, and R. G. Lopez. 2011. "Investigating Consumer Preference for Organic, Local, or Sustainable Plants." HortScience 46 (4): 610–615. ↲

Yue, C., C. R. Hall, B. K. Behe, B. L. Campbell, R. G. Lopez, and J. H. Dennis. 2010. "Investigating Consumer Preference for Biodegradable Containers." Journal of Environmental Horticulture 28 (4): 239–243. ↲

Yue, C., S. Zhao, and A. Rihn. 2016. Marketing Tactics to Increase Millennial Floral Purchases. American Floral Endowment. Floral Marketing Research Fund. ↲

Zwicker, M. V., H. U. Nohlen, J. Dalege, G.-J. M. Gruter, and F. van Harreveld. 2020. "Applying an Attitude Network Approach to Consumer Behaviour Towards Plastic." Journal of Environmental Psychology 69: 1–14. ↲

Publication date: Aug. 12, 2025

AG-980

The use of brand names in this publication does not imply endorsement by NC State University or N.C. A&T State University of the products or services named nor discrimination against similar products or services not mentioned.

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.