The productivity and ecological character of North Carolina’s future forests rest largely in the hands of over 500,000 private individuals and families who own 78% of the state’s 18.1 million acres of commercial timberland. Owners cherish the environmental, social and economic benefits the forest provides. Forest management, harvest and restoration decisions are influenced by family situation, the productivity and character of the soils, the current forest, income needs and philosophy about land and the environment.

This publication seeks to

1) encourage landowners to evaluate the current condition and potential of their forest;

2) to suggest pro-active practices which enhance forest health, diversity and productivity and;

3) to investigate forest health, tree species composition and productivity for wildlife and future forest condition through a management lens.

The collective decisions of private forest landowners will have long-term impact on the diversity, health and productivity of the forest landscape.

The Forests of North Carolina - As Variable as Our People, Our Regions and Our History

The forests of North Carolina are widespread and diverse. Natural and man-made disturbances and invasions of plants nad isease shaped both the vigor and the quality of today’s forests. North Carolinians value forests because of wildlife habitat value, water, recreational and tourism opportunities and timber. Our State's forests support the state’s tourism and forest products industry while meeting the needs of a growing population.

Forests are dynamic. Change can be dramatic and sudden or slow and tedious. Wildfire, hurricanes, tornadoes and other catastrophic events cause sudden change in forests while the natural processes of forest growth, aging and dying slowly impact forests. Native Americans managed forests by periodoic burning, slash and burn conversion to agriculture, the harvest of forests for fuel,food and many other purposes. European settlement hastened the conversion of native forests to other uses and accelerated timber harvesting. A very limited forest land base has evolved virtually untouched by man. Natural fire was common and frequent. Early timber harvests of the mature virgin forests were, in most cases, complete and early harvests were often followed by intense uncontrolled fires- creating the conditions which regenerated many “natural” forests present today. Eventually, effective and efficient fire control was introduced and wildfire became a rare, rather than common disturbance in forests. Abandonment of agricultural land created a different type of forest evolution over the landscape. In the mountains, the loss of the American chestnut to chestnut blight dramatically changed the landscape. Each of these scenarios and many other factors created a different forest condition and the result is the highly diverse forest covering close to 60% of North Carolina today.

Poor markets for low-grade and small diameter stems and the costs of harvests prompted the high-grading of past forests in North Carolina.

Concern is mounting about the future of our forests. Urbanization continues to eat away at the forest land base and is a major threat. Some changes are subtle, such as the decline in the number of stems of oak, hickory and several other species valuable for wood products and wildlife. These dramatic shifts are occurring as a direct result of fire exclusion and the common practice of repeated “high-grading,” which removes high quality stems of valuable species such as oak while leaving small and poor quality stems and less valuable species such as red maple and sweetgum.

The partially-shaded ground condition left after a high-grade harvest does not favor the regeneration of more sun-loving species such as oak, ash, black cherry, pines and many other species valuable for both wildlife habitat and forest products. Droughts, air pollution, invasive plant species and warming /changing climate also have and will continue to impact North Carolina’s future forest.

Improving Forest Health, Vigor and Productivity

Forest health and vigor can be improved where plant competition is reduced, invasive species removed or systematic fire returns. This is the main reason for such practices as forest improvement, thinning, timber harvesting, prescribed burning, and regeneration.

The restoration, maintenance and enhancement of forest health and vigor is desirable especially if your forestry goals include wildlife, recreation, aesthetics or timber. Healthy forest management practices encourage tree vigor and plant communities well adapted to the soils on your property. If well planned, many of these activities can pay for themselves and increase returns and benefits.

Consult with a Registered Forester can help you ensure that your forest is well-managed.

Well-managed and healthy forests share these characteristics:

- Tree species that are ecologically suited to your soil;

- Healthy trees with adequate room to grow;

- Minimal number of damaged, diseased or insect-infested trees;

- Protection from fire and destructive grazing;

- Controlled access to control trespass and protect roads;

- Best Management Practices to protect water and soil quality;

- Clearly marked and maintained boundaries.

Nurturing Your Forest Yields Benefits

Healthy forests are rarely untouched,. Wise management can help correct abusive practices, like high-grading, Likewsie a forest where fire has been excluded may need a repeated fire return as the appropriaterestorative treament. Active restoration may be prescribed to return desirable forest conditions. Management begins after a thourough a written plan has been prepared. That plan can link management practices to arrive at your long-term vision of the forest that you value and desire.

The assistance of professional wildlife biologists, registered foresters, soil and water specialists, recreation specialists, and natural resource professionas with investment tools are ready and able to develop your plan.

Forest Management Planning

Planning can take several or repeated steps:

- Assess. Planning entails assessing the current conditions of your forest, specifically the soils, tree species, health and vigor, stocking (determining if you have enough, too many or too few desirable trees);

- Reflect. Given the assessment, you must decide if the current forest conditions are favorable and compatible with your desires for wildlife, recreation, aesthetics and soil and water protection;

- Prescribe. Assessment and reflection lead to forest management prescriptions for each sub-unit (stand) in the forest. Prescriptions might include:

- Renewal: harvesting and replanting or regenerating stands where necessary;

- Tending and enhancement: improving the growth or vigor of stands needing attention by thinning excess trees, removing poor quality (cull) trees, fertilization, weeding;

- Ecological recommendations to enhance the stand’s aesthetics, recreational uses, diversity of plants and wildlife species and appeal to wildlife species;

- Installation and maintenance of Best Management Practices (BMPS) to protect water and soil quality.

- Act (Repeat)

Forest management plans are unique to each owner and forest condition and should be modified when forest conditions or your objectives change. The following discussion may be helpful as you assess, reflect and prescribe practices to enhance your forest.

In North Carolina, a written and implemented forest management plan can also save property taxes; qualify you for cost-share assistance, and become a first step toward sustainable forest certification. See your local forestry representative or county tax assessor for more information.

What Trees Should I Grow? Hardwoods, Pines or Both - Soil Knowledge Is the Key!

While many types of trees grow almost anywhere, healthy forests are comprised of tree species that thrive on your property and soil. An integral part of your forest assessment is to understand soil potential or productivity, the tree species best suited to those soils. Proper knowledge of tsoils can avoid harmful or iunintended consequences of management of your forest land. Many landowners are unaware of soil limitations that can affect tree growth and profitability.. Trees may need amendments or practices to optimize benefits for wildlife food, habitat and cover or profitably grow wood products for home use or sale

Right Tree, Right Site.

Pines are best adapted to soils with moisture, soil depth or textural limitations. It is futile and frustrating to expect hardwood species to thrive on worn out or eroded cropland or previously abused timberland. Best to save those less-than-perfect sites for one of the pine species. Over many decades, soils and sites canl heal and improve with proper management, so future tree species choices may be expanded through your restoration efforts.

Hardwoods evolved to thrive on specific soils and site types. Generally, moist, loamy or medium textured soils with more than 6 inches of topsoil are suitable for high quality and desirable hardwood species such as the oaks, ashes, yellow poplar and hickories. Tilling, erosion, compaction and rutting can render good hardwood sites unacceptable for decades or even centuries. While many hardwood species grow on impoverished and poor sites, they will struggle and lack the necessary vigor to produce wildlife food (mast) or quality timber. Hardwoods on impoverished sites lack vigor.

Some soils and sites have a mix of soil characteristics that allows mixed pine/hardwood stands to flourish. On these sites, the height and diameter growth of both pines and hardwoods are very similar. Diverse mixed stands are ideal for multi-purposes such as wildlife, timber, recreation and aesthetics.

Your soils must be taken into account when deciding which forest tree species will do well on your property.

How do you know the quality of your soil?

Foresters measure trees in your forest or evaluate soil conditions to determine which species might be best adapted. The quality of your land for different tree species is ranked using a concept termed Site Index (SI). SI is the predicted height of species at a given age, usually 50 or 25 years. The better the SI for a species, the better the trees will grow and thrive. For example, using northern red oak as an example:

| Site Quality | SI for Red Oak |

|---|---|

| Very Good | SI more than 80 |

| Good | SI 70-80 |

| Poor | SI less than 70 |

Generally, if your soil is poor for a given species, then it is wise to manage other species that perform better on that soil type. Also, knowing the SI for one species allows the forester to estimate the SI for other tree species not present on the site. This allows for interpretation of what is the best species or species mix for your soil. For instance, “Poor” red oak sites, may prove excellent for other species, particularly one or more pines or perhaps yellow poplar. If timber is a goal, it will be more profitable and the stands will be healthier and more vigorous if the species with a good or very good SI is managed on the property. Scientifically developed SI data and tables are available for many species and soil / site types across North Carolina.

Characteristics of good hardwood sites and soils:

- Stream and river bottoms and coves

- Soils 3 feet or more deep, with 6 inches or more of topsoil

- Mid and lower slopes

- North, northwest, east or southeast facing slopes

- Gradual, not steep slopes

- Loam, sandy loam, silt loam, sandy clay loam; soils that are friable, not plastic

- Moist, but not wet and with good internal drainage (except for swamp species)

If, after careful soil evaluation, you decide that hardwoods are not likely to thrive, then one or more of the pine or other conifer species should be considered. Restore or convert poor quality hardwood or mixed pine/hardwood stands- it's a sound forest management recommendation for many high-graded or otherwise decadent forest stands in all geographic regions of the state where the soils are suitable.

Pine species are more tolerant of poorer, steeper, hotter and drier soil conditions, in general. Growth and vigor of pines varies significantly with the species, geographic region and the site quality. White pine, Virginia pine and shortleaf pines are the major commercial pine species in the mountains. Shortleaf, longleaf, Virginia and loblolly pine are native in the Piedmont. Longleaf, loblolly and pond pine were and are common in the Coastal Plain.

Regional Conifers of Concern

Other conifers gaining ecological restoration interest are Atlantic white-cedar (coastal organic and wet mineral sites), bald-cypress (coastal and piedmont swamps / river bottoms), red spruce, pitch pine and table mountain pine (high elevation mountain sites). Conifer species selection will be based on the geographic region and the soil conditions of the property.

Confused about your forest soils? If so, call your local county Natural Resources Conservation Service and ask for a copy of your county’s published soil survey. A Registered Forester can help you interpret the soil information or measure the age and height of existing trees to estimate Site Index.

Renovate or Renew? That Is the Question!

The ultimate question: are my tree species matched to my soils and do I have enough quality trees to manage? As trees grow, they need more room.

Some basic information is needed for sound forest management decisions.

- “Are the species of trees and the general biodiversity of plants in my forest matched to the soils?” If the answer is yes, then...

- “Do I have enough stocking of desirable trees to manage the existing stand for a healthy, diverse and productive future?”

- Is the current stocking correct for multiple objectives such as wildlife and aesthetics in addition to timber?

Take Stock: Too Many? Too Few?

Stocking guides based on scientific research and experience are available for both hardwoods and conifers. Forest inventory is necessary to determine your stocking level. The following tables give desirable stockings based on the average diameter (at 4.5 feet above the ground or DBH) of trees in your forest:

| DBH | Trees Per Acre | Approximate Feet Between Trees |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 200-300 | 11-15 |

| 8 | 140-240 | 13-18 |

| 10 | 90-150 | 17-22 |

| 12 | 70-115 | 19-25 |

| 14+ | 50-90 | 22-29 |

The recommended hardwood stocking levels above have been developed primarily to provide full occupation of the site for timber production. Ideally, 40-50 very high quality, well spaced trees (per acre) that will be carried to final harvest is desirable. Somewhat fewer trees per acre may be tolerable if wildlife, recreation or aesthetics are primary goals or if wider spacing creates good conditions for understory plants you wish to keep. Overstocking (too many trees per acre) is common and overstocked stands may need to be thinned or improved by removing smaller or poorly formed trees to restore a healthy condition. Crop tree management is a strategy to identify the best trees in the forest and then release them (remove their immediate neighbors) to reduce competition for water, nutrients and especially sunlight.

How Many Pines Do I Need?

Pine stocking is easily assessed using the “D Rule” as a rule of thumb. Adequate stocking is based on the average diameter (DBH) of the stand and the distance between trees in the stand. The 1.75 X D rule recommends spacing in feet among trees to be 1.75 times the tree’s DBH in inches. For example, for 12 inch DBH trees, the ideal distance between trees is 21 feet (1.75 X 12 =21). Once the distance between trees is known, this can be converted into the approximate desirable number of trees per acre.

| DBH | Approximate Feet Between Trees | Trees Per Acre |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 10 | 410 |

| 8 | 14 | 230 |

| 10 | 17 | 150 |

| 12 | 21 | 100 |

| 14 | 25 | 70 |

The stocking levels calculated by the “D” rule are optimum levels for tree growth. Wider spacing is recommended for increased plant diversity and wildlife habit.

Mixed pine / hardwood stocking levels fall between those for pure pine and pure hardwood stands. These stands may be more dominated by pine than hardwood or vice versa, making it virtually impossible to come up with a general standard that fits all situations. As a rule of thumb, if the stand contains the minimum recommended stockings for hardwood or pine stands, the stand is likely manageable. Be sure that potential growth rates of the pine and hardwood crop trees are similar.

Forest Renovation Can Enhance All Forest Values

You have inventoried your soils, your stocking levels, stand health and vigor and forest management objectives and you have decided (with the help of your Registered Forester) to manage the current stand. There are several forest management treatments (intermediate stand management practices) you might consider in established stands.

Timber Stand Improvement (TSI) is a broad term that describes forest management activities that improve the vigor, stocking, composition, productivity and quality of forest stands. TSI is not done to regenerate a stand, but rather to add value to an existing stand.

A number of renovation and enhancement practices fall into the category of TSI:

- Sanitation or salvage cutting of dead, dying or stressed trees;

- Cull tree removal in pine, hardwood or mixed pine hardwood stands to favor selected trees;

- Prescribed burning in pine stands;

- Thinning to reduce the number of trees per acre;

- Release of young crop trees by removing overtopping and competing trees;

- Pruning to improve stem quality.

Thinning, salvage and cull tree removal can be profitable where markets exist. In many locations in North Carolina, markets for small diameter and low-grade timber are poor. So, often you must make an investment in stand improvement. Cost-share assistance for wildlife and timber improvement practices is available. Contact your local NC Forest Service or N.C. Cooperative Extension center for information.

The purpose of TSI is to favor “crop trees.” “Crop trees” are any tree that fulfills a landowner’s desired purpose.

Crop trees are:

- High value (oaks, poplars, pines, ashes, cherry, walnut, hackberry, basswood) with decreasing emphasis on species such as sweetgum, red maple, elm, locust, blackgum, cottonwood, sassafrass, boxelder and other low-value species.

- Well matched to the site, meaning the species present have potential to grow vigorously to the grade and quality desired in the soil on that site.

- Vigorous, straight and relatively knot-free.

- Well spaced with more than 1/3 of the stem in live crown.

- Free of basal defect (scars and rot), insects or other damage.

Non-crop trees targeted for removal include:

- Suppressed trees that offer little future value toward achieving your objectives;

- Poorly formed trees;

- Stems infested or affected by insects, disease, fire, wind or ice;

- Species not matched to your soil; or other objectives like mast for wildlife, water quality or beauty

- Over-mature and slow growing trees;

- “Wolf trees” (very large crowned trees which occupy excessive space);

- Any undesirable tree that directly competes with better quality crop trees.

Improvement and Profit

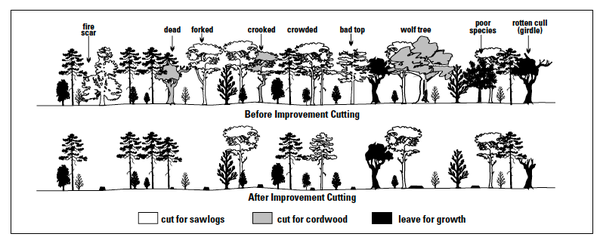

Commercial improvement harvests fall in one of two categories:

- Thinnings. Enough space is needed for the development of selected crop trees. Commercial thinning produces some income from the sale of removed trees. Failure to thin crowded stands will cause the growth rate and vigor of the stand to decline, perhaps to the point where insects, diseases and stress kill trees. By allowing more sunlight to reach the crowns of the crop trees, growth, health and vigor are maintained or improved. Added benefits include the added growth of vegetation on the forest floor (under story) which increases food and cover for many wildlife species.

- Improvement Cutting. Middle age stands with a mixture of tree species can be improved by harvesting species and low quality stems which compete with more desirable trees in the stand for moisture, nutrients and sunlight. Trees removed can be used or sold for firewood, posts, pulpwood, sawtimber or other uses. By removing less desirable species and poorly formed, diseased or insect infested trees, this practice improves the species composition and stand quality. Improvement cutting can be used to improve wildlife habitat, aesthetics or timber production.

Forest renovation pays twice; first by enhancing growth and vigor and secondly, by concentrating growth on fewer high quality trees per acre. Trees of large diameter, with 12-foot or longer clear (knot free) butt logs, are the most valuable. Ecologically, TSI can create conditions that favor the enhancement or development of more diverse plant communities, increase the vigor of trees in streamside areas to enhance nutrient uptake and water protection and/or create habitat for targeted wildlife species.

Timber stand improvement, broadly defined, includes “cull tree removal,” “weeding,” timber sanitation and salvage,” “thinning,” “improvement cutting,” “prescribed burning,” and “crop tree management.” Whether for timber solely or multiple benefits, these practices strive to keep the best trees for the site and your goals while marketing or removing those that impede the best.

Renewing Degraded Forests

Just like urban renewal, sometimes the best thing to do to a forest or a timber stand is tear it down and start over. Forests badly degraded by repeated highgrading, mature or over-mature forests (either biologically or economically) and/or forests in which by your assessment shows an inadequate number of desirable trees for wildlife, timber, aesthetics or other goals are candidates for renewal (regeneration).

Natural regeneration, which relies on seed, sprouts or existing seedlings, may re-populate the harvested area if these sources are present in sufficient quantity, desirable species and desired quality. Hardwood reforestation is typically done by “natural regeneration.” Natural regeneration will work if there is adequate seed, good seedbed conditions and enough sunlight for the selected desirable species to regenerate. If natural regeneration is judged not to be an option, seedlings or seed of selected species can be planted, assuming the selected species are well adapted to the soil / site and adequate site preparation and vegetation control is done to ensure success. Site preparation and tree planting is widely used for pines but pines also can easily be reproduced from natural seedfall.

Preplanning and the selection of the best harvest-regeneration system is the most important decision related to forest renewal.

Regeneration harvest systems should be pre-planned, as effectiveness will vary depending on soil/site, tree species and stand conditions. Systems that might be used include: single tree selection, group selection, seed tree, shelterwood and clearcutting. The system selected must be compatible with the tree species and methods you choose to regenerate (particularly the light requirements of the species), and your objectives for wildlife, recreation, aesthetics, and timber production.

If wildlife habitat manipulation is a key reason for harvesting, the owner must take into account adjoining ownerships to be sure that the timber harvest complements, rather than detracts from, the forest landscape habitat conditions. See a NC Wildlife Resources Biologist.

Single Tree and Group Selection Systems

Single tree selection and group selection involves harvesting individual trees or groups of trees. The small openings created by single tree selection allow only a small amount of sunlight to enter the forest. The resulting regeneration must be suited to full or partial shade since relatively little sunlight is allowed to reach the forest floor as a result of this method. Group selection creates a larger hole in the forest and the size of the hole will determine the amount of sunlight that enters. The trees or groups of trees to be harvested should be marked. After the harvest, the holes created in the forest are re-populated with young seedlings or sprouts. This can create a forest of multi-ages and sizes. As a landowner, you need to be aware of the predictable species that will fill in the holes (see below) and decide if selection methods can regenerate the species that meet your wildlife, recreational, aesthetic or timber goals. Extreme care must be taken to avoid damage to the trees that will be left after the harvest. Numerous roads and trails are required to conduct repetitive selection harvesting making the cost of these methods higher and the potential for soil and water quality degradation from eroding road surfaces greater.

High-grading is a form of selection. Beware of buyers offering to purchase only trees larger than a given diameter (diameter limit harvesting). This practice almost always degrades the forest in both species and health.

Seed Tree System

Almost all trees are removed in a seed tree harvest, but 4 to 20 trees are left standing to re-seed the harvested area. This method produces regeneration that is a single age and favors species that thrive in almost full sunlight (right). Advanced planning is required to ensure that the seedbed is ready and the harvest is done when the seed crop is adequate. The very best quality trees are left for seed trees in the hopes that the offspring will also be of high quality. Seed trees are usually removed after regeneration is established.

Shelterwood System

From 21-60 of the best trees per acre are left after the harvest. This method also produces regeneration of a single age and usually provides an abundance of seed, shelter for seedlings and some residual shade to reduce competition from unwanted sun loving vegetation. The “shelter trees” may be removed after adequate regeneration is in place or kept longer, giving a two-aged stand structure (deferred shelterwood) that many think more attractive.

Clearcutting System

Clearcutting removes all the merchantable trees at once. The site is then planted or natural sprouts or seed already on the site regenerates the new singleaged stand. This method favors the most sunloving species (see below). Clearcutting is opposed by many, largely because it is considered ugly by some and others erroneously equate clearcutting with water quality degradation from increased erosion. Clearcutting does create a drastic, but temporary, visual landscape change, but need not cause erosion or water impacts if appropriate Best Management Practices are used to protect soil integrity and water quality.

The purpose of a regeneration harvest is to create a new forest of the tree species best matched to your soils and objectives. Select the harvest technique that provides the required amount of sunlight for the species you desire. Selecting the wrong method or implementing it poorly will result in species shifts and failed regeneration!

| Tree species favored by various harvesting methods | |||||

| Full Shade ---> | ---> | ---> Full Sunlight | |||

| Shade Lovers | Intermediate | Sun Lovers | |||

| Fir | White pine | Eastern red cedar | |||

| Spruce | Box elder | Shortleaf pine | |||

| Striped maple | Sycamore | Table mountain pine | |||

| Red maple | White oak | Pitch pine | |||

| Silver maple | Southern red oak | Virginia pine | |||

| Sugar maple | Chestnut oak | Loblolly pine | |||

| Buckeye | Northern red oak | Alianthus | |||

| Pignut hickory | Black oak | Sweet birch | |||

| Shellbark hickory | Winged elm | River birch | |||

| Redbud | American elm | Bitternut hickory | |||

| Dogwood | Yellow birch | Mockernut hickory | |||

| Persimmon | Shagbark hickory | White ash | |||

| Beech | Fraser magnolia | Green ash | |||

| American holly | Cucumber tree | Honey locust | |||

| Mulberry | Hazelnut | Butternut | |||

| Black gum | Black walnut | ||||

| Slippery elm | Sweet gum | ||||

| Mountain laurel | Yellow poplar | ||||

| Witch hazel | Cottonwood | ||||

| Rhododendron | Pin cherry | ||||

| Black cherry | |||||

| Scarlet oak | |||||

| Post oak | |||||

| Black locust | |||||

| Willow | |||||

| Sassafrass | |||||

| Increasing Intensity of Harvest | |||||

| Single tree | Group selection | Shelter wood | Seed tree | Clear cut | |

| |----------- Partial ----------- | | | ----------- Complete ----------- | | ||||

| Tree species favored by various harvesting methods | |||||

| Full Shade ---> | ---> | ---> Full Sunlight | |||

| Shade Lovers | Intermediate | Sun Lovers | |||

| Red maple | Atlantic white cedar | Eastern red cedar | |||

| Silver maple | Bald cypress | Shortleaf pine | |||

| Pignut hickory | Boxelder | Longleaf pine | |||

| Shellbark hickory | Sycamore | Pitch pine | |||

| Sugarberry | White oak | Pond pine | |||

| Dogwood | Swamp white oak | Virginia pine | |||

| Persimmon | Southern red oak | Loblolly pine | |||

| Beech | Overcup oak | River birch | |||

| American holly | Chestnut oak | Bitternut hickory | |||

| Southern magnolia | Northern red oak | White ash | |||

| Red bay | Black oak | Green ash | |||

| Black gum | Live oak | Sweetgum | |||

| Tupelo gum | Winged elm | Yellow poplar | |||

| Slippery elm | Water hickory | Cotton wood | |||

| Shagbark hickory | Cherrybark oak | ||||

| Pumpkin ash | Swamp chestnut oak | ||||

| Sweet bay | Shumard oak | ||||

| Water oak | |||||

| Pin oak | |||||

| Post oak | |||||

| Black willow | |||||

| Sassafrass | |||||

| Increasing Intensity of Harvest | |||||

| Single tree | Group selection | Shelter wood | Seed tree | Clear cut | |

| |----------- Partial ----------- | | | ----------- Complete ----------- | | ||||

A Quality Regeneration Harvest Is the First Step of Forest Renewal

Get professional help and monitor the timber harvest. A good timber sale, harvest and successful regeneration is no accident. You should be well informed and conduct the timber sale and harvest in a professional manner. Key steps are:

- Consult a professional. Landowners who receive professional forestry advice average 23% higher income and had projected future income from the next forest 120% higher. Use only registered foresters who also are designated by the NC Board of Registration for Foresters as Consulting Foresters (CF). The CF, for a fee, estimates the volume, quality and value of the timber offered for sale, which allows you to judge whether the prices offered by buyers are reasonable.

- Carefully develop and follow a pre-harvest plan with your forester to ensure that adequate water and soil quality protective measures are included in the timber harvest plan.

- Advertise widely with an invitation to bid on the timber. The invitation should include all details of the harvest: acreage, timber description, length of contract (or deed) period, identification of trees to be cut, maps, harvesting restrictions.

- Only sell by written contract or deed that contains the same provisions set forth in the invitation to bid.

- Require that your CF monitor the harvest activity to ensure that the provisions of the written contract are followed.

- Insist that practices to protect water quality and site productivity are employed!

Knowledgeable timber sellers know the volume and value of the timber to be sold, have a pre-harvest plan that provides for soil and water protection, advertise widely, demand a written contract and monitor the harvest for contract compliance.

Remember:

Forest Land Enhancement practices can be used to tend existing forest stands or renew forests that are degraded or unhealthy. Many of these practices can pay for themselves and yield increased benefits and revenue. Financial and technical assistance is available.

As a result of the publication you can now:

- Assess and evaluate the current condition and potential of your forest;

- Reflect upon, then choose practices which will enhance the health, diversity, and productivity of your forest;

- Seek professional advice to plan and prescribe the appropriate management practices or regeneration system.

For more information and assistance refer to the list of sources on below.

Elements of a Management Plan

(1) Your goals and objectives for your forestland-

A successful plan begins with clear objectives( your specific interests and goals).

Short-term goals are targeted, typically with specific practices and time table.

Longer-term (more than 10 years) goals are usually general.

(2) Map of the Forest Property

Your plan should have a legible map and/or aerial photograph showing the location of the property and access point. Boundaries should be clearly marked and described. You can obtain aerial photographs from your County GIS ( geographical information service) , tax office or natural resource agency. Many mapping applications are available form natural resource agencies or non-profit entities, like the American Forest Foundation's MY LAND PLAN.

(3) Description of the current forest type, health, condition

Each stand and distinct forest area, should be described and correctly marked on the property map and/or the aerial photograph. Essential information can include:

- soil types;

- site productivity;

- number of acres;

- stand age;

- stocking (trees per acre);

- range of tree diameters;

- average tree height;

- standing timber volume;

- tree condition and health;

- tree species;

- topography, slope, and aspect;

- unique water quality or drainage;

- type(s) of water supply (e.g., ponds, creeks, ephemeral pools, etc.);

- other unique features.

(4) Prescribed forest management activities ( to reach desired future condition)

The “real meat” of a forest management plan is creating a timetable of planned activitie to achieve your objectives and goals ands. Management activities can be included in the previous Description section, or they can be in a separate section linked to each timber stand. Typical prescribed activities include:

- Establishing and maintaining wildlife management practices;

- Installing and maintaining water quality protection practices (BMPs);

- Marking and maintaining property lines and comers;

- Road and trail design;

- Restoration (regeneration) practices;

- Enhancing the stand’s aesthetics, recreational use and diversity of plants and wildlife species.

(5) Protection, maintenance, and modification

When preparing your plan, seek the assistance of a professional forester or resource specialist. Several key points about all plans:

- Plans are unique to each owner and forest.

- A plan is an outline or elaborate "to do " list.

- No plan is set in stone and can be modified at any time to meet new conditions, constraints or insights .

- Plans should be reviewed and updated at least every five years or as conditions change or the objectives of the owner(s) change.

- All owners and heirs, if possible, should be informed or included in plan development to ensure continuity of forest management activities.

(6) Record of activities

A record of the activities performed should be kept. This will help you remember when activities were performed so that you can better evaluate those practices. This can be included in the “Prescribed Forest Management Activities” section or attached as a separate section.

Getting Help

Advice from a natural resource management professional will enhance your forest’s potential productivity, beauty, variety, and environmental quality. Now that you’ve taken the step of determining what type of forest you’d like, the following sources or organizations can help you get there:

N.C. Cooperative Extension provides educational materials and workshops for landowners. A wide variety of publications is available from the Extension office in your county or at the online publication repository.

Extension Forestry provides educational programs as well as print and online publications.

Extension Forestry

North Carolina State University

Campus Box 8008

4231 Jordan Hall Addition

Raleigh, NC 27695-8008

919-515-5638

North Carolina Forest Service is the state agency that helps private landowners manage forestry on their property. The county forest rangers are supported by foresters who can develop a management plan to address your forestry objectives. The NCFS also administers the Forest Stewardship Program, which provides plans for enhancing your forest’s many benefits.

North Carolina Forest Service

512 North Salisbury Street

Raleigh, NC 27604

919-857-4801

North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission employs biologists who can give landowners information and technical assistance about wildlife management.

Division of Wildlife Management

1722 Mail Service Center

Raleigh, NC 27699-1722

919-733-7291

Natural Resources Conservation Service is a branch of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. District conservationists are available in most counties to help landowners protect their soil and water resources. They can provide on-site planning advice and assistance. Educational materials are available from local offices or can be found on the web site below.

USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service

4405 Bland Road

Suite 205

Raleigh, NC 27609

919-873-2100

North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality includes the Divisions of Water Resources and Energy, Mineral and Land Resources. Both divisions assist private landowners.

1601 Mail Service Center

Raleigh, NC 27699-1601

919-733-4984

North Carolina Board of Registration for Foresters oversees North Carolina’s forester registration law. Contact this board to find out if someone is a registered forester.

P.O. Box 27393

Raleigh, NC 27611

919-847-5441

North Carolina chapter, Association of Consulting Foresters, consists of private foresters who provide planning, advice, and assistance.

N.C. Chapter of the Association of Consulting Foresters

PO Box 18742

Raleigh NC 27619

919-782-7022

Publication date: Jan. 18, 2019

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.