Introduction

By making strategic land management decisions, landowners can have a forest that meets their needs.

Early twentieth-century forestry practices resulted in mining the forest for the best trees, which either left the worst trees in the woods or cleared the area for agriculture. Current forestry practices promote regenerating favorable trees and improving the quality and growth of the forest over time.

This publication will help you determine which species are best to manage in different areas. Understanding which trees grow well in each area on the property is the first step in deciding how to harvest and regenerate a forest. The next publication in this series (Part 2, Species Selection) will help you decide whether to plant or naturally regenerate species depending on your area.

Several factors influence which species grow in each area of the landscape, including landscape position. Landscape position is a combination of site aspect and topography. The site aspect is the direction the slope faces.

Other landscape positions indicate whether the site is generally upland or bottomland, the elevation, and the hydrology of the site. The sections below explain how different landscape positions in the mountains, piedmont, and coastal plain will affect species composition in those locations.

Species composition is always dependent on past land use history as well. Some species will not be where they “naturally” would exist due to lack of disturbance (such as prescribed fire, storm, harvest), lack of seed source, change in hydrology, and invasive species.

Mountains

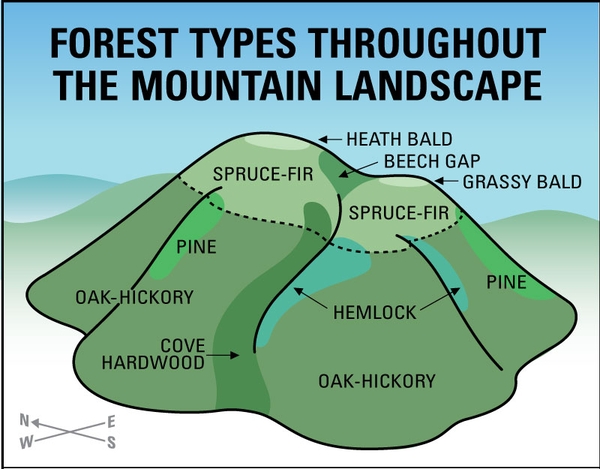

Several different features affect species composition in the mountains, including site aspect, elevation, and slope position.

Aspect

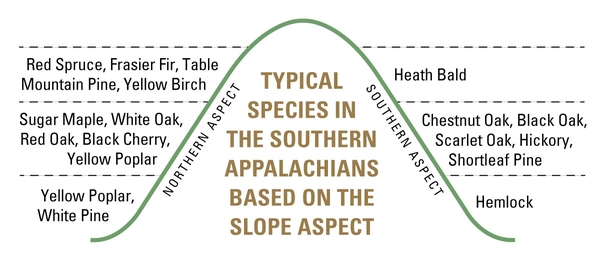

The poorest quality sites are southwest facing on the higher part of the slope, while the best quality sites are in the coves on north and northeast aspects. High-elevation, exposed sites are very limited in species while moist coves are very species-rich.

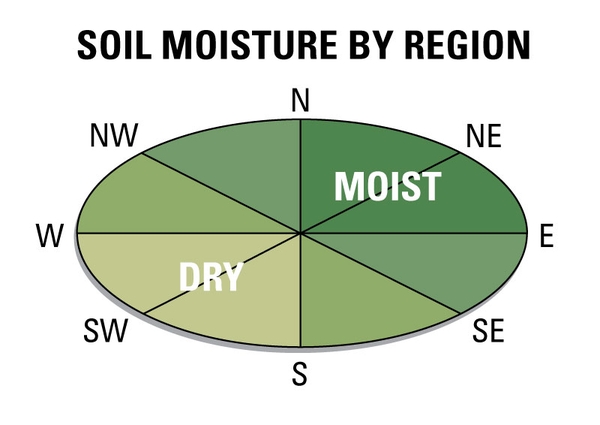

Southern aspects have more sun exposure throughout the day than northern aspects. This leads to a drier environment and poorer-quality soil (Figure 1). While eastern and western aspects have similar sun exposure, western aspects have sun exposure during the hottest part of the day. Similarly, the higher part of a hill has more wind and sun exposure than areas lower on the slope (Figure 2).

Elevation

Higher elevation areas (above approximately 4,500 ft elevation) typically consist of spruce-fir forests that lead up to mountain balds (Figure 3). Mountain balds are very exposed areas that either consist of grass or woody shrubs such as rhododendron, alder, and hawthorn. Spruce-fir forests consist of spruce, Frasier fir, and yellow-birch.

Some species may continue to grow on northern aspects up to 4,800 ft elevation, including red oak, beech, and sugar maple. Shortleaf pine and white pine are generally limited to elevations lower than 3,000 ft. Loblolly pine generally will not grow above 1,200 ft elevation.

Slope

Sheltered slopes, or hills that are shaded by nearby larger hills, are suitable for species like those on northern slopes. Many species include cove hardwoods such as northern red oak, white oak, and yellow-poplar.

Piedmont

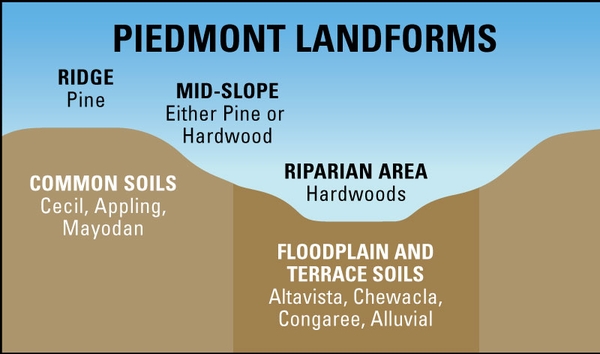

In the piedmont, both terrain and hydrology generally have greater effects on species composition.

Terrain

While southern yellow pine will grow faster on ridges, some landowners choose to grow oak on ridges based on their objectives for improving wildlife habitat and sustainably managing oak (Figure 4). An experienced forester can help you decide if managing upland oak on a ridgetop is achievable on your property.

Hydrology

Flooding potential and drainage are large factors in determining natural species composition in the piedmont. Many of the bottomland species in the piedmont are common throughout the rest of the state, including yellow-poplar, red maple, black walnut, bottomland oaks (willow oak, water oak, and swamp chestnut oak). Hardwood species on well drained slopes are similar to hardwood species on southern aspects in the mountains, including northern red oak, scarlet oak, chestnut oak, and white oak.

Yellow-poplar is the most favored species in piedmont bottomland areas. Green ash is common in bottomland forests, but it is currently not a viable species to maintain due to destruction caused by the Emerald ash borer.

Coastal Plain

Terrain

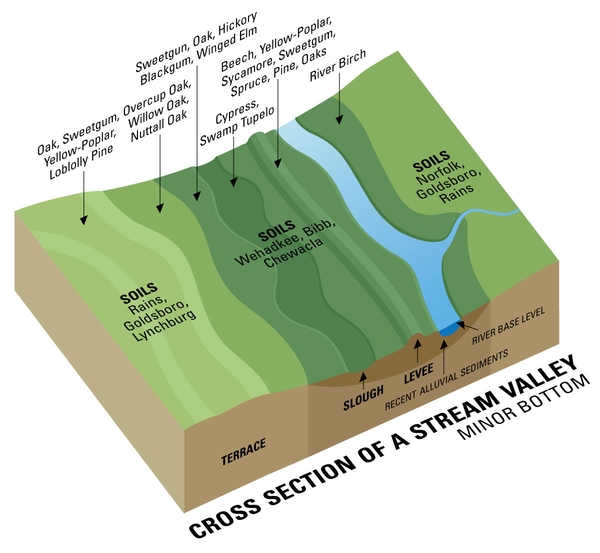

Small changes in terrain can cause a big change in species type in the coastal plain. Stream bottoms have predicable landforms from sediment deposits over time (Figure 5). These small changes determine what species can be expected to grow in a certain area.

High value tupelo and cypress are unique to these flooded swamp areas and provide significant value when the trees become mature. Many other species, including elm, ash, red maple, swamp chestnut oak, and sweetgum, are generally considered lower value species. Drained areas create highly productive conditions for growing loblolly pine. Many of these species including oaks, tupelo, cypress, and gums reach maturity in 80 to 100+ years.

Soils

Bottomland areas often have very productive soils with deep organic layers leading to more sandy soils in the upland terraces (Figure 5). Flooding regularity and soil water holding capacity both play a role in the species present on a given site.

Soils in the upland areas consists of Norfolk, Goldsboro, and Lynchford series. Stream deposits form Wehadkee, Bibb, and Chewacla soil series. These soil series are frequently flooded and poorly drained, often only allowing very water tolerant species to grow such as tupelo, willow, and cypress.

Soil Types

Landowners can use Web Soil Survey to determine the soil types present on their property. This is a free online mapping service that will provide a report of the soil types on your property and the suggested trees that will grow well on your land.

Web Soil Survey shows the site indices of different species depending on the soil type. Site index is the expected height that a species will reach at a certain age (typically 50 years), assuming trees are free to grow. To learn more about site index, see Woodland Owner Note 07 Forest Soils and Site Index.

Comparing species’ site indices can provide clues as to which species to manage on similar sites. A site with a high site index for oak (>80) can have an even higher site index for yellow-poplar (90 or 100). This typically means that yellow-poplar will grow faster and shade out oak on that site without any human intervention (such as release treatments or prescribed fire). Table 1 shows how different common timber species perform based on the site index of a given species. These species are commonly shown in a site index chart and can be determined more accurately for your site by a forester.

Additional Resources

Before you cut, contact a Consultant Forester or your local North Carolina Forest Service office to prepare a forest management plan for your property. This plan should address your species composition, age, site quality, soils, and give you a timeline for future management. A list of Consultant Foresters for each county is available through the NC Forest Service website.

Publication date: April 5, 2024

WON-64-1

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.