Problems Associated With Shade

Tree leaves can substantially reduce the amount and quality of sunlight reaching turfgrass. Food reserves of plants growing in very dense shade are typically drained, resulting in weak plants. Shade varies with the season, the characteristics of the trees, and where trees are located on the lawn. Maples, oaks, magnolias, and beeches are examples of trees with dense canopies that intercept most of the light. Some evergreens such as firs and spruces have very dense canopies but affect only small areas of turfgrass because of their narrow canopy. Pines, poplars, ashes, and birches produce a more open shade than maples and oaks. Areas with an understory, or with trees close together, cast very dense shade. Leafless, deciduous hardwood trees can block out nearly 50 percent of the sunlight in the winter, whereas the same trees in full leaf can block nearly 95 percent of summer sunlight.

Shrubs and shallow-rooted trees such as willows, maples, and beeches compete strongly with turfgrasses for nutrients and water. In clay soil, most of a shade tree’s feeder roots grow in the upper 8 inches where turfgrass roots grow. Competition extends past a tree’s drip zone, since roots can grow a considerable distance beyond this point. Reduced amounts of light, nutrients, and water produce succulent, weak turfgrass plants. They are slow to establish and are more susceptible to insects, disease, and environmental stress. They are less able to withstand traffic than plants grown in full sunlight.

Environmental conditions associated with shade favor some diseases. Poor wind movement and reduced sunlight keep the temperature cooler and increase the relative humidity in shady areas. As a result, foliage remains wet for extended periods. Although dew forms less frequently in shaded locations than sunny ones, it lasts longer because the trees hinder drying. Wet foliage encourages disease development, and thus it is important to select disease-tolerant turfgrasses.

Strategies for Managing Lawn Grasses in the Shade

Modifying the Environment

Turfgrasses will not grow in very heavy shade or under dense leaf cover. If an area gets less than 50 percent open sunlight or less than four hours of sunlight per day, it is much too shady for turfgrass to grow well. Consider removing selected trees, especially if existing trees are too close together and removing them will not detract from the landscape design. When shade is excessive, plant ground covers such as English ivy, ajuga, liriope, and pachysandra or spread pine bark and needles, crushed stone, and wood chips as an alternative to turfgrass. These ground covers are more attractive than a thin, dead lawn. For more information, check out these NC Cooperative Extension publications on lawn and lawn alternative resources. A turf-free zone at least 2 to 4 feet in diameter around a tree can improve the growth rate of small plantings by minimizing competition between tree and turf roots for nutrients and water.

Removing tree limbs to a height of at least 6 feet and cutting out unnecessary undergrowth will enhance wind movement and reduce the potential for disease. Selective pruning of the tree's crown will open the canopy and allow more light to reach the turfgrass. Removing dead and diseased limbs can enhance the health and appearance of the tree if pruning is done selectively and with care. Avoid severe pruning.

Tree-root pruning also aids in lawn performance, but care must be taken not to injure desirable trees. Maples, beeches, oaks, and certain evergreens are very sensitive to extensive root pruning. Roots should be cut cleanly, and no more than 40 percent of the functioning roots should be removed at one time. Supplemental irrigation and fertilization help reduce the harmful effects of root pruning.

The depth of shade within the dripline of a tree can result in soil erosion, exposing surface roots. Willows, elms, and maples are notorious for their surface roots. One temporary solution is to cover these surface roots with 3 to 4 inches of mixed topsoil and organic matter. Shade-tolerant ground covers can be established in these areas to give a pleasing appearance and minimize mowing problems.

Proper tree selection and placement can help minimize turfgrass loss. Trees with dense canopies, shallow root systems, or both, such as willows, poplars, ashes, and certain maples, should be avoided in favor of more desirable species such as oaks, sycamores, and elms. Contact your local Extension center for a list of the shade trees that perform best in your location.

Grass Selection

Using shade-tolerant cultivars is important when growing turfgrass in partial shade. Mixtures of tall fescue in combination with shade-tolerant cultivars of Kentucky bluegrass (80 percent and 20 percent by weight, respectively) are the best choices in most locations where cool-season grasses can be grown (see Table 1). The addition of a fine fescue (hard fescue, creeping red fescue, and chewings fescue) is beneficial in areas that will receive little maintenance. A mixture of 80 percent tall fescue, 10 percent Kentucky bluegrass, and 10 percent fine fescue by weight, seeded at 6 pounds per 1,000 square feet, is recommended.

Do not permit leaves to accumulate on the new lawn. As leaves fall, they become layered and create a mat that blocks light, air, and water movement. Remove leaves frequently until the grass is established. Some seedlings may be torn out by the rake; however, more seedlings will be lost if the leaves remain. Once the lawn is established and if the mat is not too thick, the leaves can be mulched with a lawn mower. The mulch will decay and add organic matter to the soil. However, if the cover is too heavy, it is best to remove the leaves.

In general, warm-season grasses often suffer more winter injury in shaded areas than in open, sunny locations. St. Augustinegrass is the most shade-tolerant of the warm-season grasses, followed by zoysiagrass. Centipedegrass and bahiagrass perform well under light pine-tree shade but are not as shade-tolerant as St. Augustinegrass and zoysiagrass. Bermudagrass is the least shade tolerant of the turfgrasses and should not be used in shady areas.

Cultural Practices

Lawns grown in the shade must be managed more carefully because they are often weaker than turf grown in full sun. Cultural practices must be altered to help ensure survival and enhance performance. Mow grasses at the top of their recommended mowing height (Table 1) to promote deep rooting and to leave as much foliage as possible to manufacture food for the plant.

Lawn grasses grown in the shade should generally be fertilized at the same time as turf grown in the sun, but at a lighter rate (Table 2). Lawn fertilization is not harmful to trees and shrubs and may actually be beneficial. Fertilizers associated with turfgrass, such as 12-4-8 and 16-4-8, can help to meet the requirements of trees and shrubs, thus preventing a nutrient deficiency. (Nutrient status can be confirmed by submitting a soil sample to the North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services Soil Testing Laboratory in Raleigh.) If the trees require more nutrients than can be supplied by the turfgrass fertilizer, apply additional fertilizer by soil injection or drill coring to reduce the amount of area affected and minimize the potential for turfgrass injury or loss. Keep records of the total amount of fertilizer applied to a given area so the total recommended amount for any plant is not exceeded. Overfertilization may occur if different people are responsible for the trees, shrubs, and lawn.

Irrigate the lawn deeply and infrequently to encourage deep rooting of trees and lawn grasses, reduce soil compaction, and minimize the time that the foliage is wet. Wet foliage promotes disease development.

Weed Control

Mosses (small green plants with leaves arising from all sides of a central axis) are very competitive in cool, moist, shaded locations — for example, on the north side of buildings and in wooded areas. Conditions favoring the growth of mosses are low fertility, poor drainage, acidity, frequently wet soil, soil compaction, excessive thatch, or a combination of these factors, which lead to thin, weak turf. Physical or chemical removal of mosses provides only temporary control unless growing conditions are improved. Seeds of weeds like crabgrass and goosegrass usually need high light intensity to germinate, and so preemergence herbicides are not required in heavily shaded areas. Be careful when applying broadleaf weed controls because some herbicides can injure trees and shrubs by root uptake or spray drift. Read and follow all label directions carefully.

Disease Control

Powdery mildew, brown patch or large patch, leafspot, and melting out are the major turfgrass diseases associated with shade. See NC State Extension TurfFiles for a description of the symptoms of these diseases and suggested management practices for minimizing development and damage. Planting improved, shade-adapted lawn grasses and using good cultural practices can help reduce damage from diseases. Using a blend or mixture of improved, adapted cool-season grasses, rather than a single cultivar, can help reduce potential turfgrass loss from disease.

| Lawn Grasses | Shade Tolerance | Seedling Rate (lb seed per 1,000 sq ft) |

Cutting Height (inches) |

Region of Adaptation * (Figure 1) |

| Kentucky bluegrass1 | Good | 1.5 to 2 | 2 to 3 | M, P |

| 50% Kentucky bluegrass and 50% fine fescue | Excellent | 1.5 + 1.5 | 2 to 3 | M, P |

| 10% – 20% Kentucky bluegrass and 80% – 90% tall fescue | Good | 1 + 5 | 3 to 4 | M, P |

| 10% Kentucky bluegrass, 80% tall fescue, and 10% fine fescue | Excellent | 1 + 5 + 1 | 3 to 4 | M, P |

| Tall fescue2 | Good | 6 | 3 to 4 | W, P, CP |

| St. Auguestinegrass3 | Good | NA | 2.5 to 4 | P, CP |

| Centipedegrass3 | Fair | 0.25 to 0.5 | 1 to 2 | P, CP |

| Zoysiagrass | Fair | 1 to 2 | 1 to 2.5 | P, CP |

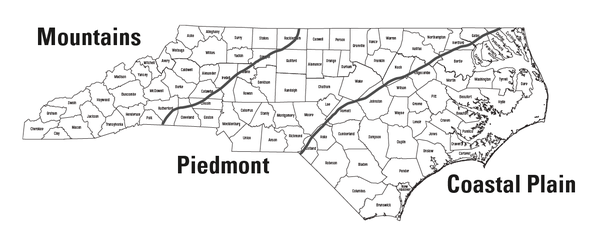

* Note on region of adaptation: M = mountains, P = piedmont, CP = coastal plain (Figure 1)

1 Adapted to mountains and piedmont regions but performs best at higher elevations.

2 Marginal performance expected in the coastal plain. Good air movement, drainage, and low traffic are necessary for persistence.

3 Usually planted vegetatively (plugged, sprigged, or sodded).

| Lawn Grass | Monthly Application Rate (lb N/1,000 sq ft)1 | Total lb N/1,000 sq ft/year | |||||||||||

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D | ||

| Kentucky bluegrass | 1⁄2 | 1 | 1⁄2 | 2 | |||||||||

| Kentucky bluegrass + fine fescue | 1⁄2 | 1 | 1⁄2 | 2 | |||||||||

| Kentucky bluegrass + tall fescue | 1⁄2 | 1 | 1⁄2 | 2 | |||||||||

| Tall fescue | 1⁄2 | 1 | 1⁄2 | 2 | |||||||||

| St. Augustinegrass | 1⁄2 | 1⁄2 | 1⁄2 | 11⁄2 | |||||||||

| Centipedegrass2 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Zoysiagrass | 1⁄2 | 1⁄2 | 1⁄2 | 11⁄2 | |||||||||

Note: Dates suggested are for the central piedmont. For the mountains, dates may be one to two weeks later in the spring and earlier in the fall. For the east, dates may be one to two weeks earlier in the spring and later in the fall.

1 Multiply by 43.5 to convert to a per-acre basis. Follow table suggestions (if soil tests aren’t available). Use a complete (N-P-K) turf-grade fertilizer with a 3-1-2 or 4-1-2 analysis (for example, 12-4-8 or 16-4-8) in which one-fourth to one-half of the nitrogen is slowly available.

2 Centipedegrass should be fertilized very lightly after establishment. An additional fertilization in August may enhance performance in coastal locations. Do not apply any phosphorus unless suggested by soil test results.

Integrated Pest Management

The Sensible Approach to Lawn Care

Many pest problems can cause your turfgrass to look bad — diseases, weeds, insects, and animals. If you are unlucky, you may have all of them at one time.

So what do you do? Use a pesticide? Or make changes in cultural practices? Both methods, and some others as well, may be needed. The balanced use of all available methods is called integrated pest management (IPM). The goal is to produce a healthy lawn and minimize the influence of pesticides on humans, the environment, and turfgrass.

IPM methods include:

- Use of best adapted grasses.

- Proper use of cultural practices such as watering, mowing, and fertilization.

- Proper selection and use of pesticides when necessary.

Early detection and prevention, or both, will minimize pest damage, saving time, effort, and money. Should a problem occur, determine the cause or causes, then choose the safest, most effective control(s) available.

When chemical control is necessary, select the proper pesticide, follow label directions, and apply when the pest is most susceptible. Treat only those areas in need. Regard pesticides as only one of many tools available in lawn care.

To learn more about IPM, pest identification, lawn care, and proper use of pesticides, contact your local Extension center or see NC State Extension’s TurfFiles.

Publication date: July 1, 2021

AG-421

Recommendations for the use of agricultural chemicals are included in this publication as a convenience to the reader. The use of brand names and any mention or listing of commercial products or services in this publication does not imply endorsement by NC State University or N.C. A&T State University nor discrimination against similar products or services not mentioned. Individuals who use agricultural chemicals are responsible for ensuring that the intended use complies with current regulations and conforms to the product label. Be sure to obtain current information about usage regulations and examine a current product label before applying any chemical. For assistance, contact your local N.C. Cooperative Extension county center.

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.