Contents

Introduction

Family Colubridae

Eastern Hognose Snake—Harmless

Southern Hognose Snake—Harmless

Glossy Crayfish Snake—Harmless

Red-Bellied Water Snake—Harmless

Southeastern Crowned Snake—Harmless

Family Elapidae

Family Viperidae

Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake—Venomous

References

Additional Resources

What are Snakes?

What are Snakes?

Snakes are reptiles in the order Squamata, which also includes lizards. Snakes are among the most modern of reptiles and have diverged from other animal groups relatively recently in geological time. Snakes are covered in scales and must shed their outer epidermal layer to grow. Snakes are ectothermic and rely on environmental temperatures for regulating body temperatures—this is why you may see snakes lying in the sun. Unlike most other reptiles, snakes lack legs and rely on muscular contractions associated with their ribs for movement.

Why are Snakes Important?

Ecological Importance

Ecologically, snakes play important roles in food webs. Snakes feed on a wide variety of prey, including fish, amphibians, invertebrates, small mammals, birds, and other reptiles—even other snakes. Snakes help to naturally control these prey species while serving as food for larger mammals, birds, and fish. As both predators and prey, snakes connect food webs and maintain a healthy ecosystem.

Economic Importance

Small rodents and invertebrates can cause a great deal of damage to property and crops. Snakes provide a natural form of control on these pest species. Large snakes, like eastern rat snakes (Pantherophis alleghaniensis), feed heavily on rodents and spare farmers from spending money on rodent control. Also, some snakes feed on insects, slugs, and grubs that may damage crops.

Religious and Cultural Importance

Although snakes are demonized in the Judeo-Christian religions, being associated with sin, the devil, and treachery, there are biblical stories depicting snakes in a positive light and as a symbol of wisdom. In addition, many other religions and cultures revere snakes. For example, in Hinduism, snakes are a figure of reincarnation, the origin of humans, rain, and wind. Native American cultures believed snakes were the reincarnation of grandfathers and refused to kill them, and some Native American cultures believed snakes were a sign of healing and the guardians of life. In the 1700s, the rattlesnake became a prominent symbol of the American Revolution and American independence with the Gadsden flag (Don’t Tread on Me). Also, snakes were prominently featured in the Join or Die political cartoon attributed to Benjamin Franklin that encouraged the Colonies to unite against British rule.

Medical Importance

Snake venoms contain unique organic chemical compounds with medical applications. For example, snake venom from rattlesnakes and other pit vipers is used to treat certain forms of cancer and high blood pressure. In addition, snake venoms are used to create antivenoms, which save lives by blocking destructive venom proteins from binding with their target(s). Researchers have developed antivenoms that are capable of treating snake bites from multiple species. As scientists learn more about the molecules in snake venom, they may discover more compounds and medical applications.

Where are Snakes?

Native snakes occur everywhere in the world except the North and South Poles, Greenland, New Zealand, Ireland, and Hawaii. However, Hawaii has recently become inhabited by invasive nonnative snakes. Snake diversity is highest in the tropical regions due to resource availability.

Biology of Snakes

Senses

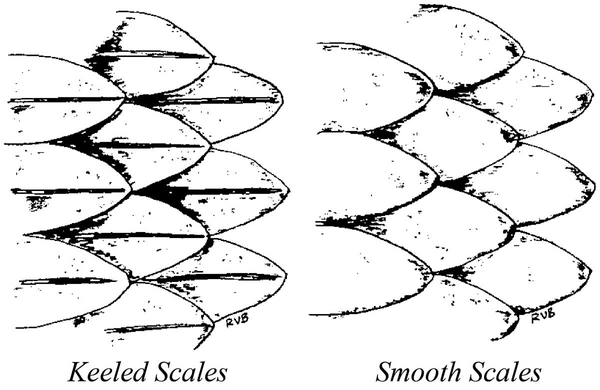

Snakes rely on the key senses—sight, hearing, and smell—for detecting prey and avoiding predation. However, snakes do not hear or smell in conventional ways. Snakes lack outer ears and have very rudimentary vestiges of an inner ear. However, snakes can still sense vibrations stemming from sounds or movements through their bodies. Snakes have external nares, or nostrils, that are used only for respiration. A snake flicks its tongue out to collect particulate matter from the air and then inserts the tongue into a specialized organ called Jacobson’s organ (Figure 1). The Jacobson’s organ processes the particulate matter, allowing the snake to smell or taste the air. In addition, some pit vipers have special organs called loreal pits that allow them to sense heat signatures.

Scales

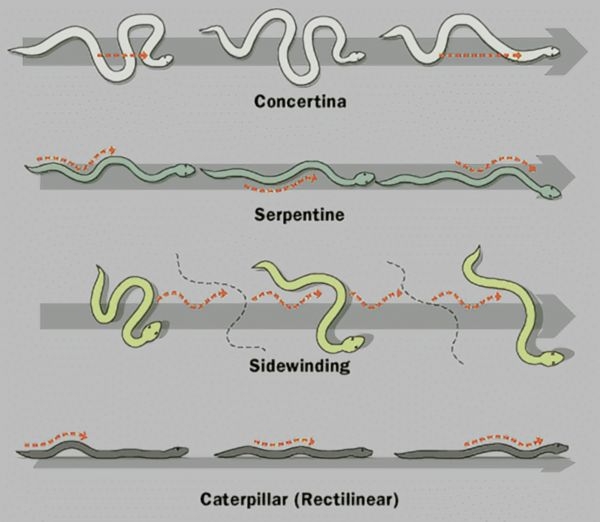

The scales that cover the epidermis of a snake can either present a smooth feel and shiny appearance or a rough feel (Figure 2).These differences are caused by the absence or presence of a keel on each scale. The keel is a raised ridge on the scale that scatters light differently than a smooth scale, resulting in a duller appearance. Also, the ridge results in a rougher texture. Snakes can have different degrees of keel and may be referred to as weakly keeled or strongly keeled. Also, snake scales display multiple colors and patterns within and among species. These colors and patterns serve different biological functions for snakes, such as camouflage or aposematism (using conspicuous colors to warn predators it is toxic). These colors and patterns can be used to differentiate species.

Locomotion

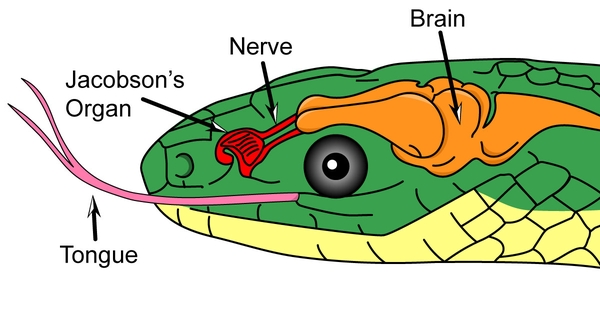

There are five main forms of locomotion in snakes, including lateral undulation (or serpentine), sidewinding, concertina, rectilinear, and slide-pushing (Figure 3 – with the exception of slidepushing). Lateral undulation is the most common form of locomotion in snakes. This motion involves slithering in an “S” formation using the ventral, or bottom, scales to gain traction and propel the animal forward. Different species may use different forms of locomotion more often than others, and different forms of locomotion may be used for different situations, depending on the surfaces and obstacles snakes are traveling through.

Venom vs Poison

Although the terms “venom” and “poison” both describe forms of toxins, they are quite different. Poison is a toxin that may be ingested or absorbed into the body (through the skin or a mucous membrane), whereas venom is typically injected into the body through a bite or sting. Most venomous snakes possess fangs, which are enlarged hollow teeth that inject venom into prey, whereas other venomous snakes deliver venom through chewing action of the teeth. Although one genus of snake (Rhabdophis; only found in Asia) is truly poisonous, most snakes capable of toxin delivery are venomous. In North Carolina, the six venomous snake species cause bites that are medically significant. Venoms are a mixture of different types of toxins, and venom composition can vary within and among species. There are two primary types of venom—neurotoxic or hemotoxic. Neurotoxic venom occurs primarily in elapids (eastern coral snake [Micrurus fulvius]) and causes tingling, pain, and paralysis. Hemotoxic venom is more typically exhibited by viperids (like copperheads [Agkistrodon contortrix], cottonmouths [Agkistrodon piscivorus], pigmy rattlesnakes [Sistrurus miliarius], and rattlesnakes [Crotalus spp.]). Hemotoxic venom causes tissue degradation, red blood cell destruction, hemorrhaging, and localized blood clots.

Reproduction

Most snakes reproduce sexually. Snakes have two main approaches to giving birth: egg-laying and live-bearing. Egg-laying snakes are known as oviparous. Eggs laid by oviparous snakes are leathery and pliable, unlike bird eggs. Live-bearing snakes are known as ovoviviparous; the snake holds membranous eggs within her body that hatch inside and are later born as live young from the cloaca, which is an opening used for waste elimination and reproduction. Snakes may deposit eggs in or near natural or artificial cover or underground.

Diet

All snakes are carnivorous, and many species have highly variable diets, feeding upon a variety of organisms. Conversely, some species have highly specialized diets and feed primarily on a single organism (for example, queen snakes [Regina septemvittata] primarily feed on crayfish).

People and Snakes

Ophidiophobia, or fear of snakes, is common and may have biological, biblical, mythical, and pop culture roots. Nevertheless, snakes provide many biological and economic benefits and are an integral part of ecosystems where they naturally occur. Also, snakes have historical, medical, and religious importance around the world. However, due to irrational fears and myths, snakes have long been demonized and deliberately killed. We hope that dispelling common misconceptions about snakes and providing opportunities to learn about the ecological benefits of snakes will help people tolerate them and respect their role in ecosystems.

Venomous Snakes compared to Nonvenomous (Harmless) Snakes

In North Carolina, venomous snakes can be distinguished from nonvenomous (harmless) snakes by a few key morphological features (Figure 4). The pupils of the venomous copperhead are elliptical compared to the rounded pupils of the harmless eastern milk snake (Lampropeltis triangulum). In addition, venomous snakes in the family Viperidae have pits located below their nostrils that are lacking in nonvenomous snakes native to North Carolina. Also, viperids tend to have triangular-shaped heads. However, this characteristic can be tricky to distinguish because some nonvenomous snakes will flatten their heads and flare their jaw outward, thus making their heads appear wider. Elapids are difficult to distinguish from some harmless snakes because they lack pits and elliptical pupils. Ultimately, learning patterns and other identifying characteristics is the best way to distinguish venomous snakes from those that are harmless.

Snake Bites

Snake bites generally occur when people intentionally handle or unintentionally encounter snakes. In North America, being bitten by a venomous snake is rather uncommon and rarely results in death. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 7,000 to 8,000 people are bitten by snakes in North America each year; of those, only about five die. If you are bitten by a venomous snake, seek medical attention immediately. Although not all snake bites are avoidable, you can avoid most by not handling snakes, using caution, and showing proper respect for the animals.

Managing Snakes

There are many reasons snakes may occur in and around homes. Human dwellings can provide warmth, shelter, prey, and water. Identifying the attractant(s) is helpful in managing property to reduce the number of snakes and snake encounters. For example, snakes are attracted to hiding places, such as downed wood, pots, rocks, and other debris. In particular, piles of wood, metal, or plastic may be attractive to snakes for thermoregulation—regulating their body temperature. Snakes may use openings between rocks, bricks, or other building materials for refuge, to aid in skin shedding, or to locate prey. Snake encounters may be reduced by minimizing the presence of these structures.

The best way to discourage snakes from your property is to identify and address what may be attracting them. Homeowners can eliminate pests like rodents and insects from buildings by making entry more difficult. For example, sealing off small openings or cracks will make it more difficult for animals to enter buildings. To deter snakes, it is best to remove any objects that may provide shelter for snakes or prey species.

If you encounter a snake inside a building, it is important to properly identify the species to assess the risk involved. If a snake is nonvenomous, homeowners can easily remove the animal on their own with little or no risk to themselves or the animal. Homeowners can sweep nonvenomous snakes out of a home with a broom. Alternatively, homeowners can pick up nonvenomous snakes and remove them by hand; however, there is some risk of being bitten. Thick gloves and long sleeves may be helpful in preventing a bite. However, never try to move venomous snakes, no matter what clothing you wear.

If you are uncertain of the species of a snake or you suspect it to be venomous, do not attempt to handle the snake. It is best to leave the snake alone or contact a wildlife professional if the snake does not leave. Unless you are an experienced snake handler with the proper permits, you should never attempt to handle or remove a venomous snake on your own.

Once you remove a snake from a building, it should be released onto the same property where the building stands. Snakes have distinct home ranges, and moving them large distances has been shown to result in an increased risk of mortality. Also, some snakes may carry diseases, so it is important to avoid moving snakes from one location to another to minimize the spread of diseases and avoid potentially harming other snakes.

Commercial snake repellents exist, but these products can be harmful to people and pets if not used properly and have not been scientifically shown to be effective in repelling snakes.

Attracting Snakes

Some property owners may want to attract snakes to their property for ecological or economic benefits, or just because they like snakes. Having snakes in gardens can help control rodents and other pests that may destroy plants or harbor disease.

To attract snakes to your property, do the opposite of what we previously described. Snakes will select locations that provide food, cover, and areas to cool off and warm up. Property owners could maintain places to hide, support dense vegetation, and provide water sources to attract snakes.

Common Misconceptions

Common Misconceptions

“Snakes are mean.” Snakes vary in their responses to encounters with humans, differing by species and the temperament of individuals. In general, most snakes will remain still or flee to avoid an encounter with humans. If escape is not possible, snakes may take a defensive posture and strike (depending on species).

“Snakes are evil.” Snakes, like all animals, are driven by biological processes and are not moral or immoral. Snakes simply eat, reproduce, and regulate their body temperature to survive.

“Snakes form hoops to chase people.” No snake species has been shown to form a hoop to move like a wheel. This myth is probably based on the feeding behavior of the mud snake (Farancia abacura). The mud snake primarily feeds on slippery, long-bodied amphibians and will orient its body like a hoop when eating. In addition, when encountered, a mud snake may curl up in a circle with its head under its tail for protection, thus resembling a hoop. But they do not roll or chase people.

“Eastern milk snakes steal milk from cows.” Eastern milk snakes feed primarily on small mammals, snakes, and lizards. Eastern milk snakes do not suckle milk from cows but are drawn to barns to prey on rodents.

“Eastern rat snakes crossbreed with copperheads to create venomous black snakes.” Eastern rat snakes and copperheads are not closely related and cannot produce viable offspring. In fact, eastern rat snakes and copperheads have different forms of reproduction. Copperheads are live-bearing and eastern rat snakes are egg-layers.

“Snakes can sting with their tails.” Although most snakes have pointed tails, their tails are harmless and not strong enough to break the skin of a person. No snake possesses a stinger. Venomous snakes use fangs, which are modified teeth, to inject venom into prey.

Snakes of North Carolina

North Carolina is home to 38 snake species. Thirty-two of these species belong to the family Colubridae, five belong to the family Viperidae, and one belongs to the family Elapidae. Although some colubrids possess a mild form of venom, they are all considered harmless to people. That is because the venom does not target mammalian prey or because their delivery method is less efficient than hollow fangs near the front of the mouth. In some cases, both reasons apply. North Carolina snakes in the families Viperidae and Elapidae are venomous, and their bites are considered medically significant to people. But if you treat snakes with respect and caution, you may avoid bites.

The North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission recognizes some snakes as needing special protection. These species are listed as endangered, threatened, or of special concern.

Figure 1. Snake morphology with tongue protruded showing Jacobson’s organ, also known as the vomeronasal organ.

Image from User: Fred the Oyster / Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.5

Snakes of North Carolina Index

| Family | Common Name | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colubridae | Banded Water Snake | Nerodia | fasciata |

| Colubridae | Black Racer | Coluber | constrictor |

| Colubridae | Black Swamp Snake | Liodytes | pygaea |

| Colubridae | Brown Water Snake | Nerodia | taxispilota |

| Viperidae | Copperhead | Agkistrodon | contortrix |

| Colubridae | Corn Snake | Pantherophis | guttatus |

| Viperidae | Cottonmouth | Agkistrodon | piscivorus |

| Colubridae | Dekay’s Brown Snake | Storeria | dekayi |

| Colubridae | Eastern Coachwhip | Masticophis | flagellum |

| Elapidae | Eastern Coral Snake | Micrurus | fulvius |

| Viperidae | Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake | Crotalus | adamanteus |

| Colubridae | Eastern Garter Snake | Thamnophis | sirtalis |

| Colubridae | Eastern Hognose Snake | Heterodon | platirhinos |

| Colubridae | Eastern Kingsnake | Lampropeltis | getula |

| Colubridae | Eastern Milk Snake | Lampropeltis | triangulum |

| Colubridae | Eastern Rat Snake | Pantherophis | alleghaniensis |

| Colubridae | Eastern Ribbon Snake | Thamnophis | sauritus |

| Colubridae | Eastern Worm Snake | Carphophis | amoenus |

| Colubridae | Glossy Crayfish Snake | Liodytes | rigida |

| Colubridae | Mole Kingsnake | Lampropeltis | rhombomaculata |

| Colubridae | Mud Snake | Farancia | abacura |

| Colubridae | Northern Water Snake | Nerodia | sipedon |

| Viperidae | Pigmy Rattlesnake | Sistrurus | miliarius |

| Colubridae | Pine Snake | Pituophis | melanoleucus |

| Colubridae | Pine Woods Snake | Rhadinaea | flavilata |

| Colubridae | Queen Snake | Regina | septemvitatta |

| Colubridae | Rainbow Snake | Farancia | erytrogramma |

| Colubridae | Red-Bellied Snake | Storeria | occipitomaculata |

| Colubridae | Red-Bellied Water Snake | Nerodia | erythrogaster |

| Colubridae | Ring-Necked Snake | Diadophis | punctatus |

| Colubridae | Rough Earth Snake | Haldea | striatula |

| Colubridae | Rough Green Snake | Opheodrys | aestivus |

| Colubridae | Scarlet Kingsnake | Lampropeltis | elapsoides |

| Colubridae | Scarlet Snake | Cemophora | coccinea |

| Colubridae | Smooth Earth Snake | Virginia | valeriae |

| Colubridae | Southeastern Crowned Snake | Tantilla | coronata |

| Colubridae | Southern Hognose Snake | Heterodon | simus |

| Viperidae | Timber Rattlesnake | Crotalus | horridus |

References

Beane, J. C., A. L. Braswell, J. C. Mitchell, W. M. Palmer, and J. R. Harrison. 2010. Amphibians & Reptiles of the Carolinas and Virginia. Second edition. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

Bosmans, R. 2012. Snakes. University of Maryland Extension Specialist, Home and Garden Information Center.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. “Venomous Snakes,” a Workplace Safety and Health Topic. 2018.

Krysko, Kenneth L., and F. Wayne King. 2014. “Online Guide to the Snakes of Florida.” Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL. [Online: September 2014]

Moon, B. 2001. Snake Locomotion. Comparative Physiology and Functional Morphology. University of Louisiana at Lafayette. Accessed 29 Jul 2019.

Ovaska, K., and C. Engelstoft. 2003. “Attracting Snakes into your Backyard.” Government of British Columbia. Accessed 29 Jul 2019.

Parkhurst, J. 2010. “Managing Wildlife Damage: Snakes.” Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Tech. Accessed 29 Jul 2019.

Prada, E, L. Miková, R. Surovec, and M, Kenderová. 2012. Complex kinematic model of snake-like robot with holonomic constraints. Mezinárodní vědecká konference k problematice technologických a inovačních procesů Technnológia Europea 2012, At Hradec Králové, The Czech Republic, Volume: 2.

Ruppert, B. 2016. “The Rattlesnake Tells the Story.” Journal of the American Revolution. Accessed 29 Jul 2019.

Stanley, J. W. 2008. “Snakes: Objects of Religion, Fear, and Myth.” Journal of Integrative Biology 2:42–58.

Thompson, H. 2015. “What’s the Difference Between Poisonous and Venomous Animals?” Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution. Accessed 29 Jul 2019.

Tkaczyk, F. “Snake Tracks: Understanding Serpent Locomotion.” Alderleaf Wilderness College. Accessed 29 Jul 2019.

Publication date: Aug. 21, 2019

Reviewed/Revised: July 12, 2024

AG-472-02

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.