What Is Thinning?

Thinning is the cutting or removal of trees to accomplish a management objective. For timber purposes, thinning regulates the number, quality, and distribution of the remaining “crop” trees. If the cut trees are saleable, the thinning is deemed “commercial.” When markets do not exist for the removed trees (usually because of size), the thinning is termed “precommercial.”

Why Thin?

The number of trees per acre affects yield and value growth of pine trees. Stand density (or tree stocking) can affect the size and vigor of trees. Much like site productivity, trees grow poorly if there are too many or even too few per acre. Unlike most crops, trees live long enough and grow large so that the optimum number per acre changes with age. Controlling stand density by thinning can improve the vigor, growth rate, and quality (and value) of the remaining “crop” trees.

Forest thinning benefits the forest landowner in four ways:

- Shorter time to market: Growth is concentrated on fewer, faster growing trees. Faster growth reduces the time required to reach harvestable size, and larger trees bring higher stumpage prices.

- Growth is focus on crop trees: Only high-quality trees are permitted to grow to final harvest, eliminating volume accumulation on low-value trees.

- Forest health is increased: Trees which would stagnate or die before final harvest can be utilized.

- Management pays early! Intermediate harvests can provide periodic income and enhance growth, access, fire protection, and wildlife values.

Biologically Speaking

Pine trees need growing space as they compete for water, nutrients, and light. Using these inputs, the green needles in the crown manufacture food to increase the tree’s size. The larger trees can support an expanded crown which, in turn, can produce still more food. As a result, the tallest trees are most often the most successful competitors. They “dominate” the canopy where they receive direct sunlight from above and the sides. Since pines cannot tolerate shade, their branches thin out and die from the ground up, as the trees become shaded and crowded. As trees get overtopped, their live green crowns decrease. Over time trees become less competitive and eventually die. Due to this natural “thinning” process, a dense natural pine stand or plantation will be reduced to a few hundred trees per acre by age 40.

If nature has its own “thinning” process, what is the advantage of thinning deliberately?

Most sites produce about the same total wood volume—be it a lot of small trees or a few large ones. Total wood volume, however, is rarely a good indicator of market value. Because value increases with diameter, individual tree size determines the product and market value. For example, an individual tree can double or even triple in value as it becomes usable as small or large sawtimber, respectively.

Diameter growth is greatly influenced by stand density. To produce sufficient food for vigorous diameter growth, each tree must retain at least one-third of its height in live crown. With normal, uncontrolled competition, the amount of live crown declines to less than one-third on all except the dominant trees in a stand. Therefore, natural thinning occurs only after diameter growth has been slowed on most trees, including many crop trees.

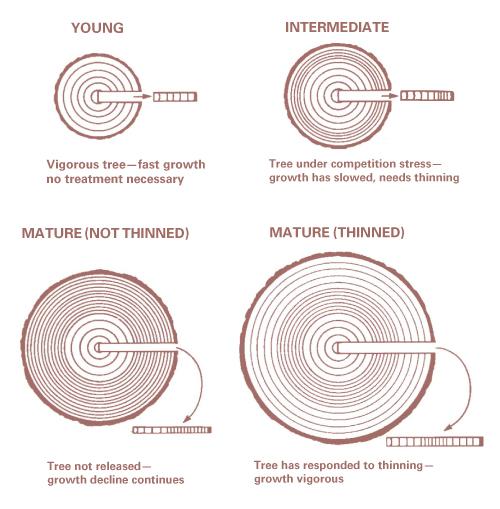

The maximum response to thinning usually is found among the remaining vigorous trees (co-dominants) once these are relieved from competition of their subordinates (Figure 1). Dominant trees have already "out-competed" smaller neighbors so that only removing "suppressed" trees seldom prompts much response. Smaller trees can only benefit from competition removal if and when they develop sufficient live crown. Thinnings should be performed early in the stand's life since height growth, vigor, and ability of the crown to expand decline with age. Larger volume and better wood properties make continuous fast growth preferable to the "slow-fast" response illustrated in Figure 1. Therefore, several light thinnings are better than a single heavy thinning.

How to Measure Stand Density

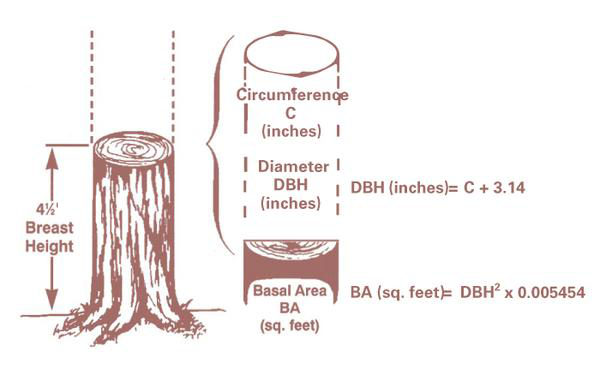

The optimum number of trees per acre at a given age depends upon their size. Foresters use "basal area" to describe stand density and evaluate stocking. A tree's basal area (BA) is the stump-top surface area at 41⁄2 feet above the ground (breast height). Measured in square feet, BA is determined by the tree's diameter at breast height (DBH). DBH is commonly measured using a flexible tape pulled around the circumference graduated in inches and tenths on a scale which divides the circumference by 3.14 (Figure 2).

Basal area per acre is the total of the BA's of all trees on that acre. It may be estimated by measuring all trees on a small plot of known size and then inflating the total value to a per acre figure. For example, ten 12-inch trees on a one-tenth acre plot (a square 66 by 66 feet or a circle with a 37.25-foot radius) would total 7.9 square feet per one-tenth acre, representing 100 trees with 79 square feet per acre (Table 1).

|

Diameter Breast Height |

Basal Area Per Tree |

Number of Trees Per Acre for the Following Basal Area (BA) |

||

|

80 |

100 |

120 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

.20 |

410 |

510 |

600 |

|

8 |

.35 |

230 |

290 |

345 |

|

10 |

.55 |

150 |

180 |

220 |

|

12 |

.79 |

100 |

130 |

150 |

|

14 |

1.07 |

70 |

90 |

112 |

|

16 |

1.40 |

60 |

70 |

86 |

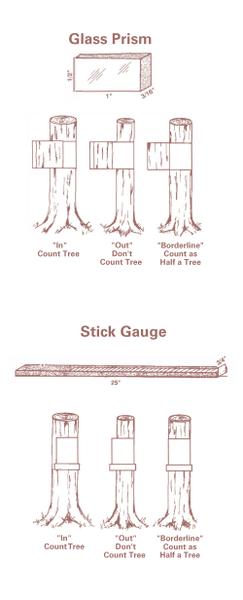

A much simpler method to determine basal area per acre involves using a glass prism or other type of angle gauge. Each "in" tree (those too large and too close to be offset completely by the gauge) counted while turning one complete revolution (360 degrees) represents a certain basal area per acre regardless of tree size—an amount called the instrument's "factor." The basal area per acre is estimated by counting all "in" trees surrounding a sample point and then multiplying the tally by the instrument's "factor." For example, with a "10-factor" gauge, one revolution counting nine "in" trees would indicate 9 × 10 feet or 90 square feet per acre of basal area, regardless of the tree sizes (Figure 3).

A simple "10-factor" angle gauge may be constructed by fastening a 3⁄4-inch wide target to the end of a 25-inch long (Biltmore) stick. Glass prism gauges may be inexpensively purchased from forestry suppliers.

When to Thin

Basal area per acre tends to remain fairly stable over much of the forest stand's life. However, it stabilizes at a maximum in the east above 130 square feet per acre , too high to permit optimum crop tree growth. The goal of thinning is to reduce the basal area per acre to between 60 and 110 square feet as early and as often as practical, keeping only straight, healthy, vigorous, and evenly spaced crop trees. Table 1, showing the basal area of trees by diameter, also includes the approximate number of trees per acre of each size which would total 80, 100, or 120 square feet per acre.

Naturally regenerated stands sometimes have such a large number of trees per acre that precommercial thinning becomes advisable. Precommercial thinning should be performed as soon as overstocked conditions are identified, and the stands are safe from the regrowth of sprouts and weeds—generally between age 4 and 8 years. Precommercial thinning may be most beneficial where tree density compromises tree ability to express dominance and thin themselves naturally.

How to Thin

Foresters consider site quality, species, age, tree size, and vigor of a stand, as well as stand density, when prescribing a thinning. They adjust density based on site productivity, objectives, and market. Location, markets, and logger availability influence the thinning prescription. Weather affects recommendations, with frequent, lighter thinnings favored in locations particularly susceptible to wind, snow, and ice damage.

Foresters may mark rows or individual trees to be removed with paint or ink spots both at breast height and at the ground line. The marks are useful to estimate the volume to be removed, to calculate the basal area of crop trees to be left, and to check on the harvest operation to see that it is done properly. Trees to be removed should include the crooked, defective, forked, diseased, and dying, as well as undesirable species. Practical considerations have led to a practice called row-thinning for equipment access (for example, every fifth, fourth, third row). Depending upon the logging crew, selective removal from remaining rows may also be part of the thinning prescription.

The true value of thinning involves the trees which remain in spite of the attention given the trees being cut. Therefore, frequent oversight is recommended to ensure that crop trees are protected during thinning operations.

Occasionally, crop trees are marked for leaving rather than marking trees to be removed. This is particularly helpful in stands with numerous small or low value trees, areas of diseased, damaged, and deformed trees, and stands which might be thinned intermittently, perhaps by the landowner. In all cases, care must be taken during marking and harvesting to avoid damaging crop trees and to minimize damage to the site.

Pre-commercial thinning may focus more on numbers of trees rather than a density target. Because of the small tree size and long time before harvest, preference is given to the lowest cost method for reducing the number of trees per acre. No fewer than 400 to 500 well-distributed potential crop trees per acre should be left. Precommercial thinning may be done with hand tools or mechanically by chopping or bush hogging 7- to 8-foot parallel swaths, leaving 1- to 3-foot wide strips of standing trees. Sometimes an alternative is a combination of the two methods, manually thinning the 3-foot strips to about 450 trees per acre. Prescribed fire, chemicals, or fertilizers have sometimes been used as pre-commercial thinning techniques with varied results.

A simple rule of thumb that may be useful for estimating crop tree density is based on the diameter and spacing. Spacing is the distance between a given tree and its neighbors. The D × 2 Rule determines spacing (in feet) among crop trees to be 1.75 times the tree’s diameter (in inches). For example, two 12-inch trees to be left should be separated by 24 feet (12 × 2 = 24). Application of this rule would leave approximately 80 square feet of residual basal area per acre without regard to species, site, or stand conditions (Table 2).

|

Diameter Breast Height (DBH) |

Distance Between Trees |

Number of Trees Left |

|

6 |

12 |

436 |

|

8 |

16 |

170 |

|

10 |

20 |

110 |

|

12 |

24 |

75 |

|

14 |

28 |

55 |

Specific Recommendations

Thinning recommendations for individual pine species, including timing, intensity, and repetition intervals, follow:

Loblolly: On the better coastal plain and piedmont pine sites, loblolly is the most productive of the southern pines. Intensive management could call for thinning to about 60 to 110 square feet of basal area per acre as frequently as every five years. Practical considerations usually limit the number of thinnings to once or twice during a rotation. Consider thinning in the “teenage” years 13 to 17 on the best sites with commercial-sized trees. Start later using longer intervals on medium or poorer sites and in more dense stands. Such a schedule can produce sawtimber in as little as 30 to 35 years, depending on soil quality.

Longleaf: This species is generally found on dry, sandy coastal plain sites. Thinnings may be advisable about every 10 years to reduce the basal area to 50 to 100 square feet per acre. While precommercial thinning is usually not necessary, the stocking of dense young stands should be reduced as early as practical to about 400 to 500 well distributed seedlings per acre.

Shortleaf: Although common throughout the piedmont and mountains and prized for its sawtimber value, shortleaf pine is slower growing than loblolly on most sites. In mixtures with loblolly pine, this species is likely to be removed in intermediate cuttings. In pure stands, similar guidelines apply for loblolly, with thinnings as frequent as 10 years reducing basal area to approximately 60 to 100 square feet per acre.

White: Widely planted in the mountains and upper piedmont, white pine is extremely fast growing and frequently develops very high stand densities on the better sites. Thinnings should be light and frequent, leaving residual basal areas above 90 square feet per acre and as high as 120 in older stands on good sites. Poor pulp markets for this species have led to recommendations to plant at wide spacings. This minimizes the need for early thinning.

Conclusion

Thinning is a more expensive harvesting operation than clearcutting and, therefore, returns less money to the landowner. However, the improved utilization, intermediate cash flow, and the increased value of the final crop can make thinning a profitable management decision. Not all partial cuttings are thinnings nor are they all good investments. “Cutting the best and leaving the rest” or “leaving those small (young?) trees to grow” can be “high-grading” rather than thinning. Proper thinning requires that an adequate stand of “crop” trees remain. Landowners should seek the advice and assistance of a professional forester prior to marking or marketing a thinning.

For an overview of how to manage for resilient pines, see the Resilient Piedmont Pines: Risk Reduction Guide.

Publication date: Oct. 1, 2019

Reviewed/Revised: July 10, 2024

WON-13

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.