Soybean water use can exceed 25 inches during the growing season. Water may come from soil storage, precipitation, and irrigation. The growth stage determines the water requirements of the soybean plant and its susceptibility to wet and dry stress. Kranz & Specht (2012) estimated that more than 60% of total water use occurs during the R1 to R6 growth stages. To manage water for soybean production, growers must consider multiple factors, including growth stage, depth of root penetration, soil types, topography, and the ability to manage water in the field through an irrigation and drainage system.

Soybean Rooting

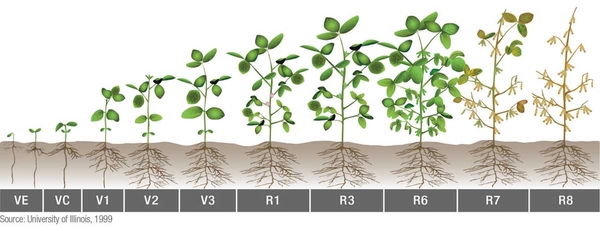

Soybean plants have a taproot, as shown in Figure 1. The taproot typically develops in the first weeks after the plant's emergence. Other roots branch off of the taproot as the plant continues to grow. Understanding how roots develop and at what depth the soybean plant roots exist is fundamental to effectively managing water throughout the growing season. In North Carolina soybean production, the primary root system responsible for water uptake is typically in the top 12 inches of the soil, although roots extend far below this depth. About 70% of water intake for soybean occurs in the top 12 inches of the soil profile, whereas less than 30% of water intake occurs below this depth (mostly from 12 to 24 inches deep) (USDA-NRCS 2010). Rooting depth is variable across North Carolina and can be impacted by many factors, including hardpan, pH, rock layers, and depth to the water table. Although soybean roots can extend well below 24 inches, most water management decisions should be based on water behavior in the top 24 inches of the soil profile.

Soils

Soil texture plays a critical role in the amount of water available to the soybean plant. There are three primary soil textures: sand, silt, and clay. The ability of the soil to provide water to the plant is a function of the texture. Sand holds the least amount of plant-available water, followed by silt, and then clay. The soil texture influences the likelihood of wet and dry stress during the growing season. Dry stress is more likely to occur in sandy soil, whereas wet stress is more likely in silt or clay. Sandy soils require frequent irrigation in smaller amounts. Silt and clay soils require more intensive drainage. Coarse soils like sand typically hold less than 1.3 inches of water per foot of soil. Finer-textured soils hold about 1.8 to 2.0 inches of water per foot of soil. For more information, see Soil, Water, and Crop Characteristics Important to Irrigation Scheduling.

Topography

Topography refers to elevation differences in a field and plays a pivotal role in the movement and storage of water in the soil. A low area in a field typically receives runoff from higher elevations and is subjected to surface ponding, which tends to create wet conditions for the plant. When wet conditions occur, no oxygen is available in the soil, causing plant growth and nutrient uptake to slow and potentially leading to plant death. River bottoms, valleys, and field potholes are areas prone to wet conditions. In addition, coastal plain sites in North Carolina are relatively close to sea level and have prevailing high water tables (shallow, saturated areas of the soil) that create excessive wet stress for plants. In contrast, water in high-elevation sites (hills or mountains) is prone to run off to low areas. Runoff leads to less infiltration of precipitation, which reduces the amount of water that enters the soil and replenishes plant-available water.

Growth Stages and Water

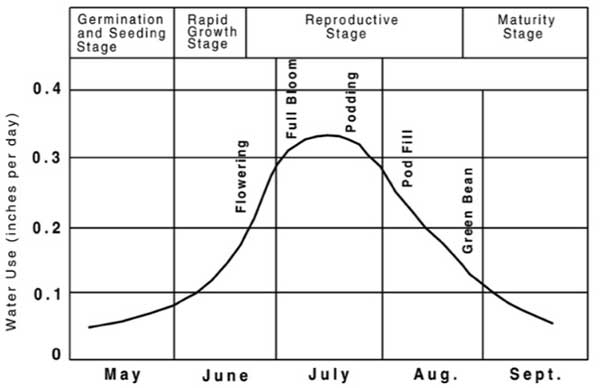

Soybean growth stage is a major factor in determining the water use of the plant and the magnitude of stress created by drought or wet conditions. Soybeans require different amounts of water at different stages of development (Table 1). During early growth stages (VE–V1), soybean plants require very little water. Water needs greatly increase as the plant continues to produce roots and develop above ground and below ground (V1–R1). During reproduction periods (R1–R5), water needs are at their highest. After the R5 stage, water requirements decrease significantly.

Modified from Tacker and Vories n.d.

Fluctuating periods of wet and dry stress throughout the growing season can have cumulative impacts on final crop yields. Wet stress during emergence can impact root development and plant populations, which if followed by a drought can exacerbate drought stress. Understanding cyclical patterns is key to managing water during the growing season. Although each growth stage can be susceptible to wet or dry stress, final yields are a function of the cumulative stress that occurs throughout the growing season.

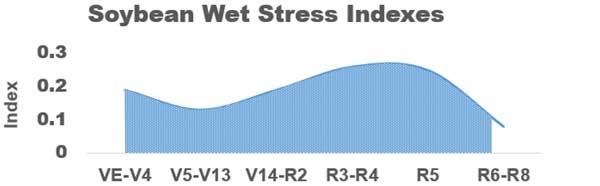

Figure 2 shows a unitless index of wet stress for soybean as affected by growth stage. These data were derived from greenhouse studies to quantify susceptibility of soybean crops to excess moisture stress (Evans 1991) for use in the DRAINMOD computer model developed at North Carolina State University (Skaggs 1978). Soybean plants are susceptible to wet stress throughout the growing season, but they are extremely susceptible during the emergence period (VE) and from R1 to R5. The yield impact from wet stress during these growth stages is more severe.

Figure 3 shows the range of soybean susceptibility to dry stress by plant growth stage (Sudar et al. 1979). Note that both Figure 2 and Figure 3 present a unitless index to quantify the yield impact of stress at different growth stages. Each type of stress is considered independent of the other. The relative trends and magnitudes are the important takeaway. As indicated in Figure 3, soybeans are not as susceptible to dry stress early (VE–V14) or late (R5–R8) in the growing season. At reproduction (R1–R5), however, the impact of dry stress increases compared to the beginning of the growing season. Understanding the relationship of water stress susceptibility at different soybean growth stages should guide water management decisions throughout the growing season.

Water Management (Evapotranspiration, Drainage, and Irrigation)

Evapotranspiration (ET) refers to the amount of water that is returned to the atmosphere through either soil evaporation or plant transpiration. Typically, ET is greatest during the summer months, when daytime and nighttime temperatures are highest. At this time, soybeans are in late vegetative and reproductive growth periods throughout North Carolina. During these growth periods, corresponding to late June through mid-August, soybean transpiration rates peak (Table 1), and water demand intensifies. Figure 4 depicts the typical daily water demand graphically for soybean by growth stage.

Two management practices, drainage and irrigation, control the amount of water that is available in the soil to meet soybean water demand.

Drainage utilizes open ditches, tile drainage, or surface drainage (also known as land leveling or surface grading) to manage excess soil water during the growing season. A ditch or tile drain removes subsurface water when the water table is higher than the depth of the ditch or drain. Such systems are designed and installed to reduce prolonged saturation in the soil. When effectively managed, ditches or tile drains can increase the level of oxygen available for the plant during and after intensive precipitation. The required intensity of drainage is a function of the soil type and spacing and depth of the ditch or tile drain. In general, the coarser the soil, the deeper the drain depth, and the closer the drain spacing, the higher the drainage intensity of the system. Ditch or tile systems can be highly effective at reducing waterlogged conditions, but they should also be managed to not overdrain the fields. Overdrainage can occur when the water table falls significantly below the root zone, thus removing too much water from the soil profile. This situation can lead to depletion of water in the root zone and ultimately create a deficit of soil water later in the growing season. Drainage water management can be accomplished with outlet controls that can reduce or stop drainage. Ideally, the drainage system should be used at full capacity to reduce wet conditions in the top 12 inches of the soil (the primary rooting zone) and then operated to limit drainage to conserve water once waterlogged conditions are no longer apparent within the primary rooting zone.

Surface drainage promotes uniform water infiltration while reducing shallow depressions that are prone to waterlogging. This type of drainage is accomplished by using a land plane, box blade, soil pan, or other grading system to level the field to uniform surface grade. The operator can create surface drainage by using their best judgment or through more precise techniques, such as laser or real-time kinematic (RTK) grading systems. In North Carolina, a combination of subsurface (tile and deep ditches >3 ft) and surface drainage is often required to manage wet stress in soybean production.

Irrigation is the practice of adding water to soybean fields when drought stress is anticipated. Adequately addressing soybean water needs requires an understanding of the actual plant-available water per inch of soil, plant rooting depth, plant growth stage, and impact of dry stress on yield. Growers should also factor predicted weather conditions into irrigation planning. The greatest impact of wet and dry stress on final soybean yield overlaps during the reproductive stages (Figure 2 and Figure 3); therefore, it is important to consider potential upcoming rainfall events when deciding to irrigate. Irrigation prior to intensive rainfall can reduce existing dry stress but can exacerbate wet stress after rainfall, thus offsetting the yield benefit of the irrigation.

The best practice in soybean water management is to monitor moisture levels in the soil, commonly accomplished via the feel method, ET irrigation scheduling (with checkbook balancing method), or soil moisture sensors. The feel method involves simply digging a shallow hole and feeling the soil to estimate moisture content, an acceptable means of assessing the need for irrigation. A more comprehensive method of irrigation scheduling is to use a checkbook-balancing approach to estimate water utilization. This can be accomplished by accounting for available soil moisture, plus daily rainfall or irrigation, then subtracting an estimated daily soybean ET rate. Once the soil is at a moisture content suitable for irrigation to start, you can use Table 1 or Figure 4 to estimate daily soybean irrigation demand if rainfall isn't anticipated. A more complex method of monitoring moisture levels involves using ET information from either a weather station at the field or a nearby weather station operated by the North Carolina State Climate Office corrected for soybean crop coefficients. Soybean crop coefficients (Kc) are used to convert the measured ET for a reference grass crop to soybean. Simply multiply the measured ET by the Kc factor in Table 2.

Modified from USDA-NRCS 2010.

A third method of determining when to irrigate is to use soil moisture sensor devices such as a tensiometer, which measures soil water tension in the field. A tensiometer measures the amount of work a soybean plant must perform to extract moisture from the soil. The more negative the reading is, the less water is available for the plant. Another acceptable device is a volumetric soil moisture sensor, which measures the water in the soil on a percentage basis. The readings acquired from both types of sensor devices are affected by soil texture. Over time, a farm manager should become acquainted with the corresponding plant-water availability for the specific reading of the instrument to properly schedule irrigation. The manager should also consider differences in soil types within a field when making irrigation decisions.

The depth to the shallow water table (if present) should also be considered when making drainage and irrigation decisions. You can determine the depth to the water table by boring a shallow hole in the soil (36 to 48 inches deep) and observing whether water comes into the hole over time (for example, 15 minutes to 6 hours, depending on soil type). You can create a more permanent monitoring setup by installing a screened well in the hole that can be routinely checked. If water is observed within 36 inches of the soil surface, consider not irrigating until there is no water present within the top 36 inches. Certain soil types allow for water to move from the water table to the root zone via a process known as upward flux. In upward flux, water moves vertically toward the root zone from the water table. In some soils, particularly sandy loams, this process can significantly contribute to meeting ET demand without the need for substantial surface irrigation.

In soils with a high water table, it is imperative that irrigation and drainage operators identify the level of the water table relative to the root zone to make informed drainage and irrigation decisions. If the water table is within 12 inches of the soil surface, you should use the full intensity of your drainage system. For most North Carolina soils, you should strive to establish drainage that maintains a water table between 20 and 36 inches to promote water conservation and reduce the need for supplemental irrigation in soybean production.

Summary

Managing water-related stress in soybean is a function of multiple factors. Successful management of water stress involves a comprehensive understanding of the probability of encountering either wet or dry stress at any point during the growing season. For example, if your farm is located on the top of a hill, there is a greater likelihood of observing dry stress during the growing season than if it is in a river bottom or valley. You must understand how soil texture affects the potential for water stress. Sands do not have a high water-holding capacity and will be prone to dry stress. As a result, more intensive irrigation will be required. Conversely, clays have a high water-holding capacity and will be prone to wet stress that requires intensive drainage. Understanding soybean rooting depth and water use at different growth stages and recognizing the impact of either wet or dry stress on crop yield are essential in proper water management. Knowledge of these concepts ultimately determines when, how, and in what amount you should irrigate or drain. You should also incorporate weather forecasts in the decision-making process. A proactive approach to water management is always best. In soils with a high water table, water management decisions should include real-time awareness of the water table's location. Significant water for crop use can come from below the root zone to meet ET demand, reducing the need for supplemental irrigation, but at the same time can contribute to wet stress, especially when irrigation is done prior to large rainfall events. Managers must account for the natural process of upward water movement from a water table when deciding on irrigation and drainage needs.

Proper water management in soybean can be accomplished through investment in and timely management of both drainage and irrigation infrastructure. Water-related stress during the growing season is cumulative and related to plant growth stage. In any given year, simultaneous management of both excesses and deficits in soil water conditions throughout the growing season is essential to achieve high soybean yields.

References

Dong, Y., L. Kelley, and S. Miller. 2020. Efficient Irrigation Management with Center Pivot Systems. E3439. Michigan State University Extension.

Evans, R. O., R. W. Skaggs, and R. E. Sneed. 1991. "Stress Day Index Models to Predict Corn and Soybean Relative Yield Under High Water Table Conditions." Transactions of the ASAE 34 (5): 1997–2005. ↲

Kranz, W. L., and J. E. Specht. 2012. Irrigating Soybean. G1367. University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. ↲

Rogers, D. H. 1997. "Irrigation." In Soybean Production Handbook. C-449. Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service.

Skaggs, R. W. 1978. A Water Management Model for Shallow Water Table Soils. Report No. 134. Water Resources Research Institute of the University of North Carolina. ↲

Sudar, R. A., K. E. Saxton, and R. G. Spomer. 1981. "A Predictive Model of Water Stress in Corn and Soybeans." Transactions of the ASAE 24 (1): 0097-0102.

Tacker, P., and E. Vories. n.d. "Chapter 8: Irrigation." In Arkansas Soybean Handbook. MP197. University of Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service. ↲

USDA-NRCS. 2010. North Carolina Irrigation Guide. ↲

Publication date: Sept. 22, 2025

AG-992

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.