Demand for local food has increased over the last decade. Many consumers believe local food is fresher, has less chemical contamination, and is of higher quality than imported food (Sloan 2007). For instance, millennials—those who came of age in the early part of the 2000s—are more concerned than previous generations about the origins of their food (Halzack 2015).

Millennials, like people across all age groups, are leading very busy lives, often with little time or desire to cook at home. While a growing number of consumers are paying closer attention to the origins of their food, they also want convenience built into their food choices—flavorful options that are less perishable than farm-fresh products and require minimal preparation at home.

How do you generate more money from local beef, milk, seafood, or produce?

One way is to enhance the value of these foods to consumers. A broad view of adding value is to transform food from its original state to a more marketable state. For instance, you could change sensory qualities, portion size, or convenience of preparation to make products more appealing to consumers.

Examples of increasing economic value include removing the shells from wild-caught shrimp so the final product is ready-to-cook right out of the package, dehydrating or freezing vegetables to extend their shelf life, or crafting cheeses or ice cream from dairy products. In each case, the value to the customer is enhanced.

Consider attributes consumers want in their food—for example, no preservatives or genetically modified ingredients, ease of preparation, unique flavors, or extended shelf life. By creating goods with those desired features, producers can generate differentiated products that are no longer simple commodities. Similar products compete against each other in the marketplace, but differentiation allows producers to tailor their pricing and market strategy to generate consumer awareness and loyalty. Furthermore, new ingredient and manufacturing technologies now allow processors to meet consumers’ rising expectations for health, taste appeal, and convenience.

Manufacturing a new food product, however, is not as simple as preparing a home meal. As a producer, you need to understand how to select, receive, portion, weigh, blend, and cook mass quantities of ingredients using different processing technologies. You also need to know about and comply with state and federal food-safety regulations and inspection requirements to safely process your product and protect public health.

Assessments must be conducted to learn where to apply monitoring and control measures at raw materials receiving and during processing and storage. These evaluations will ensure your new products are safe for consumers to eat.

You will need to know what kind of packaging will fit the distribution channel (refrigerated, frozen, or shelf-stable) that will best attract your customers’ attention or meet their storage needs. You will also need a comprehensive business plan to successfully market your new products.

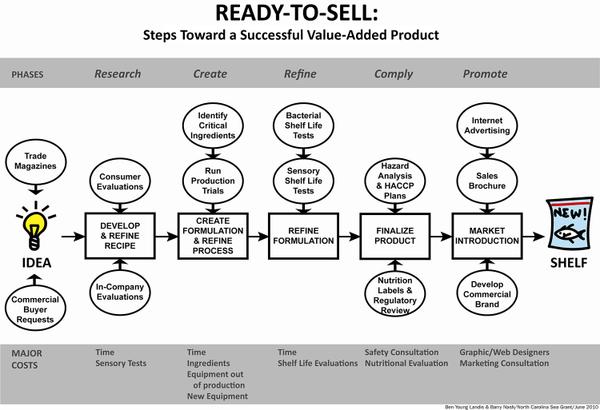

Creating value-added products is time intensive, taking up to a year or more to develop, but you will achieve significant rewards if your developmental process is well planned and executed (Figure 1).

The purpose of this publication is to introduce you to general principles for successfully creating new products and where to find specific guidance at each developmental stage.

Step One: Ideation

Your first step for developing a new product is to decide what kind of product you want to offer. Ideas for new products can come from a number of sources: food magazines, food industry newsletters, food blogs, food industry trade shows, websites, as well as friends or your employees. You should also search social media, such as Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest Recipes, and Instagram, for novel concepts.

In general, consumers are searching for foods that offer health benefits, taste appeal, and ready-to-cook or ready-to-eat convenience right out the package. When you consider product options, take a look at those already offered by the retailers or food distributors with which you want to do business. As one grocery retailer said, “I’m looking for unique items—I have enough barbecue sauces to last a lifetime.” If you already have a relationship with a retail or wholesale buyer, ask that buyer for specific advice about what types of products would readily sell at their establishments.

Balance the kind of product you want to produce and market against your manufacturing and delivery capabilities. You may need specialized ingredients to enhance the nutrition, palatability, or shelf life of your product. Food-safety regulations may influence your choice of processing and packaging options. Depending on your ingredients, manufacturing requirements, and method of distribution (at room temperature, refrigerated, or frozen), you may need to contract with a co-packer to produce your product. Also consider labor, packaging, and transportation costs for the markets you want to serve. These expenditures will determine if you can sell your new product at a price that covers your manufacturing, distribution, and marketing costs while providing you an acceptable profit.

Before investing your time and capital to transform a product concept into a saleable item, seek both business and technical assistance. A business specialist can help you assess the costs of investing in the operation and the anticipated returns. A technical specialist can answer questions related to equipment, labor needs, and food safety, among other topics. For low- and no-cost guidance, see the suggestions below and check with your local community college or small business development center.

Before meeting with these experts for help, identify a few key details about your product and process. You should know who your target customer is, what consumer needs your product will satisfy, how you will sell your product (i.e., refrigerated, frozen, or shelf-stable), and if you will sell directly to consumers (i.e., farmers markets or online), retailers (i.e., grocery chains or gourmet food stores), or bulk distributors (i.e., Pate Dawson or Sysco Foods).

For regulatory direction on processing value-added foods with seafood, milk, or produce, contact the Food & Drug Protection Division at the North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services. For manufacturing processed foods with beef, pork, or poultry, contact the Meat & Poultry Inspection Division.

For business guidance, contact the North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services (NCDA&CS) Marketing Division.

For technical direction on processing seafood, contact North Carolina Sea Grant or the North Carolina State University Seafood Laboratory.

For guidance on processing meats, fruits, or vegetables, contact your county North Carolina Cooperative Extension center or the Department of Food, Bioprocessing and Nutrition Sciences at NC State University.

Step Two: Develop a Recipe

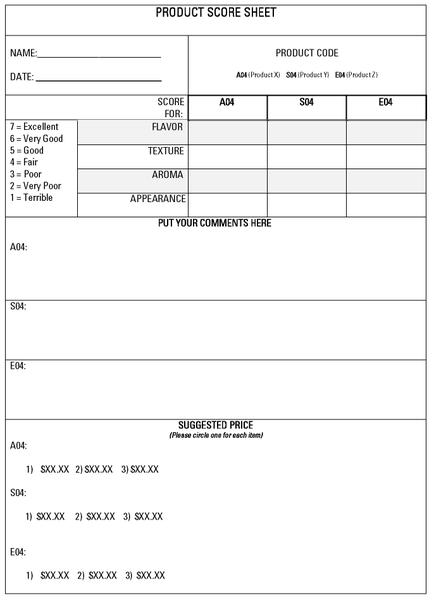

Once you decide on a product, develop a standard recipe and evaluate its appeal to potential consumers. An inexpensive method for assessing the acceptability of your product is to conduct sensory evaluations or “taste tests” with friends or your company personnel. Sensory ballots are available from North Carolina Sea Grant that allow individuals to rate the flavor, texture, color, aroma, and appearance of food on a scale from 1 to 7 where 1 is “unacceptable” and 7 is “excellent” (Figure 2).

In addition to numerical scores, encourage your sensory participants to comment on what they like and dislike about your product and why. This information, in addition to the scores, will help you determine how best to modify your recipe to remedy any deficiencies identified by your informal sensory panel.

If you want more detailed feedback from your target customers, you may wish to conduct large-scale consumer evaluations of your product. The Sensory Service Center at NC State offers fee-for-service product testing for North Carolina businesses. Contact the Sensory Service Center to schedule a consultation.

Step Three: Create a Product Formulation

Once you are satisfied with your recipe, you are ready to transfer your developmental work to a manufacturing setting. Weigh the ingredients in your recipe so you can convert US measurements, such as tablespoons, cups, ounces, and pounds, into metric units (grams). Then calculate the percentage each ingredient contributes to the entire recipe by dividing the weight of an ingredient by the total weight of all the ingredients in your recipe and multiply by 100. You will use this formulation to calculate the quantity of ingredients for a specific batch size (e.g., 100 pounds, 1000 pounds, or more) when you begin manufacturing your new product on a commercial scale (Table 1).

|

Recipe |

Weight (Grams) |

Formulation (Percent) |

|

1 ½ pounds cooked shrimp |

681 |

60.5333 |

|

1 cup light cream |

190 |

16.8889 |

|

½ cup mayonnaise |

95 |

8.4445 |

|

3 ounces softened cream cheese |

85 |

7.5555 |

|

3 tablespoons chopped onions |

32 |

2.8445 |

|

2 tablespoons fresh lemon juice |

22 |

1.9555 |

|

1 ½ teaspoons prepared mustard |

16 |

1.4223 |

|

½ teaspoon Worcestershire sauce |

3 |

0.2667 |

|

¼ teaspoon Tabasco sauce |

1 |

0.0888 |

|

1125 g |

100% |

You may need special ingredients to enhance or maintain your product’s sensory qualities over time or extend its shelf life. For instance, additives called gums control the loss of water from meat and vegetable ingredients to keep them moist over time. Natural antioxidants, such as rosemary, protect the flavor of your product, and lactic and acetic acids can suppress the growth of spoilage bacteria.

The Institute of Food Technologists, a food industry trade organization, offers an online directory featuring product and contact information for 200 companies that supply ingredients to food manufacturers. If you desire specific guidance on formulating your product with specialized ingredients, contact North Carolina Sea Grant or the Department of Food, Bioprocessing, and Nutrition Sciences at NC State.

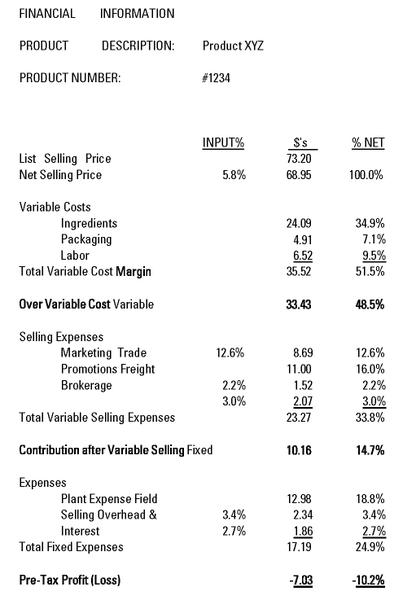

Enter ingredient levels and prices into a spreadsheet so you can calculate how adjustments to your formulation will alter your product’s total manufacturing costs. You can then balance this information against a target retail cost and sensory quality to create an item that is both appealing and profitable to manufacture. You should consistently record and track your product’s finances so you can quickly identify trends that positively or negatively affect your profits. An NCDA&CS business specialist can help you develop a spreadsheet to scrutinize your product’s ingredient and processing costs (Figure 3).

Step Four: Refine the Formulation and Enhance Production Efficiencies

At this stage, you will adjust your formulation and manufacturing process to ensure you can mass-produce your product without sacrificing its sensory qualities. Several to-scale tests or production trials may be needed to verify that your processing equipment operates properly and your production methods deliver the highest yields of saleable product.

If you lack processing infrastructure, consider a shared-use kitchen to conduct your manufacturing tests. These operations furnish entrepreneurs with commercial processing equipment to mass-manufacture value-added foods for retail or wholesale customers. Producers pay a fee and provide their own labor. For a list of shared-use facilities in North Carolina, visit the NC Shared-Use and Business Incubator Kitchens section of NCDA&CS’s Marketing Division web page.

You could also contract with a co-packer to test and produce your product. Co-packers are established food businesses that will process and package your product according to your specifications. An advantage of using a co-packer is you can devote more time to distributing and promoting your product. Manufacturing costs, however, can be expensive.

The Food Processing Using a Co-Packer fact sheet from Oklahoma State University contains guidance on selecting a co-packer. For a list of businesses within the state that offer co-packing services, visit the NC-Based Co-Packers section of NCDA&CS’s Marketing Division web page.

If you want to construct or upgrade your own facility, consult with NCDA&CS to design a production area that meets the requirements for safely manufacturing products. Consultations are free of charge to North Carolina businesses. Contact the department’s Food & Drug Protection Division at 919-733-7366 to schedule a consultation with a regulatory specialist. If you plan to process beef, pork, or poultry products, contact the NCDA&CS Meat & Poultry Inspection Division at 919-707-3180.

During your manufacturing trials, you will make significant adjustments in your process to enhance production efficiencies. To ensure these adjustments do not negatively impact the sensory quality of your product, conduct informal sensory evaluations with friends or employees as described earlier in this publication. Your goal is to incrementally improve manufacturing proficiencies without sacrificing the desirable characteristics that will make your product appealing to your target customer.

When you have achieved a production formulation that meets your cost and quality targets, your next step is to conduct a shelf-life evaluation to determine the time it takes for spoilage microorganisms to grow and make your product unfit to eat. For more information on shelf life testing, contact a North Carolina Sea Grant food-processing specialist to assist with shelf life evaluation for both seafood and other food products.

Step Five: Regulatory Assessments

You have finalized the formulations and production process for your new product. Next you need to comply with state and federal safety regulations and nutrition labeling requirements.

Your product may be subject to regulations, such as the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) food-safety rule, that help processors identify where in their manufacturing process they can prevent, eliminate, or reduce to an acceptable level biological, chemical, or physical hazards that can make food unsafe to eat. All processors need sanitation programs to ensure food-handling practices throughout their manufacturing facilities do not contaminate products, potentially making them unsafe for consumption. If your value-added product will be manufactured at a co-packer or commercial kitchen, that business entity is responsible for meeting these regulatory requirements. If you plan to manufacture the product yourself, be sure to fully understand and assess regulatory compliance costs and include them in your business plan.

To learn more about safety rules and sanitation regimes for processing commodities, contact the NCDA&CS Food & Drug Protection Division, North Carolina Sea Grant, or the NC State University Department of Food, Bioprocessing, and Nutrition Sciences.

Assistance with developing nutrition labels for your final product is available through NC State University’s Department of Food, Bioprocessing, and Nutrition Sciences.

Step Six: Market Introduction

Whether you plan to sell directly to consumers, retailers, or wholesalers, you need a website to provide your target customer with information about your company, what makes your product unique, and where it can be purchased. Websites are basically online sales brochures where you can continuously update photos, videos, customer testimonials, and other promotional features without incurring print costs.

Retail and wholesale buyers will want to review sales literature prior to meeting with you in person to determine if your item fits with their existing line of value-added products or meets consumer needs. A sales brochure should feature a photo and brief description of your product—brand name, type of packaging, shipping-case dimensions, and pricing—that all buyers require for an initial evaluation (Figure 5).

For more guidance on generating sale materials and websites, contact NCDA&CS’s Marketing Division, North Carolina Sea Grant, or North Carolina Cooperative Extension.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Dr. Barbara Blakistone, Kristin Davis, Art Defeo, Annette Dunlap, Rebecca Dunning, Doris Hicks, Anita MacMullan, Audrey Pilkington, Laura Ritter, and Scott Wiles for reviewing and providing helpful edits to this publication.

References

Halzack, Sarah. 2015. "Your Healthy Eating Habits Are Eating into the Packaged Foods Industry." Washington Post, February 13.

Sloan, Elizabeth. 2007. "Top Ten Functional Food Trends." Food Technology. 61(4):35.

Taylor, Joyce. 2003. "Shrimp Dip." Mariner’s Menu: 30 Years of Fresh Seafood Ideas. North Carolina Sea Grant, 122.

Additional Resources on Product Development

Nash, Barry. 2010. Ready-to-Sell: Developing Value-Added Seafood Products.

Nash, Barry, Charles Hudson, and Dan Kauffman. 2014. Adding Value to Seafood: Facilitating Innovation through Partnerships.

This material is based upon work that is supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, US Department of Agriculture, under award number 2013-68004-20363. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

CEFS is a partnership of North Carolina State University (NC State), North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University (NC A&T), and the North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services (NCDA&CS).

More information: Center for Environmental Farming Systems

Local Foods Publication Series Editor

Joanna Massey Lelekacs, Coordinator for Local Foods

NC Cooperative Extension Center for Environmental Farming Systems

Publication date: Feb. 2, 2016

LF-008

The use of brand names in this publication does not imply endorsement by NC State University or N.C. A&T State University of the products or services named nor discrimination against similar products or services not mentioned.

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.