Introduction

The sun rises on a home or business, and they begin their feast. The sounds of crunching and chewing can’t be heard but are most certainly there. Soldiers stand ready to defend their home, alerting their family to intruders through vibrations in the floor, communicating everything without speaking a word. Each tiny bite causes the cost to go up, and it continues until, eventually, the walls will come down, and the bones are brittle. This is the reality of a structure infested with Eastern Subterranean termites (Reticulitermes flavipes) in North Carolina. These silent invaders can go unnoticed for decades without proper surveillance and can lead to immense financial burden and loss for those affected. While we provide an extensive overview of termite surveillance and management in our publication, Monitoring and Management of Eastern Subterranean Termites, it is important to also understand the lifecycle and colony structure of this pest in order to remain vigilant. Read on to learn more about the greatest threat to your home and business in North Carolina.

Lifecycle & Habitat

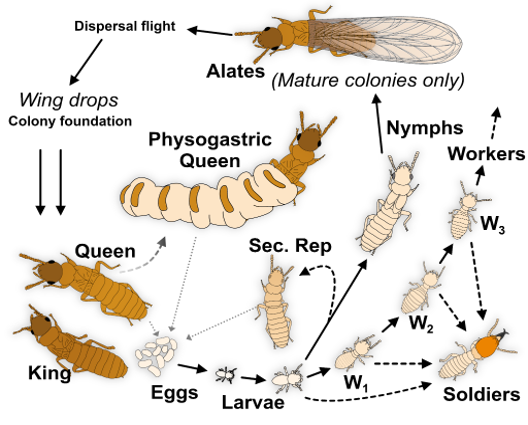

Termite colonies, like all other social insect colonies, begin with a male-female pair of mature reproductives (alates) that have flown from their colony to start anew. In the case of the Eastern subterranean termite, the most common termite species through North America, the alates are dark brown to black in color and roughly 8-10mm in length from head to the tip of their wings (Figure 1). Once alates have mated and “gone to ground,” they begin developing the colony as the new Queen and King – unlike other social insects, which have queens only. An individual queen typically produces between 5,000-10,000 eggs per year, leading to slowed colony growth, and can take up to a decade to begin producing the next generation of alates. Mature colonies have been found to contain up to several million members, but on average they contain roughly 300,000 insects. Within the colony everyone plays a role, and in the case of termites these can be workers, soldiers, primary reproductives, and even secondary reproductives – more below. Termites undergo incomplete metamorphosis, progressing from egg to nymph and then to adult (Figure 2).

In terms of habitat, Eastern Subterranean Termite colonies typically establish within the soil, below the frost line, as termites are highly sensitive to shifts in temperature and moisture due to their soft exoskeleton. However, as it relates to structures, it is not impossible for colonies to establish at higher levels in the soil, or even within the structure itself. Termite colonies need an abundance of food and moisture in order to survive, and a leaky pipe or standing water within a crawlspace can provide the much needed moisture far closer to their food source. Within North Carolina, Eastern Subterranean Termites can be found in all counties, and so homes and structures across the state are at constant risk.

Colony Structure

As eusocial insects, those insects characterized by having cooperative brood care, overlapping generations within the same colony, and division of labor, Eastern Subterranean Termites are characterized by a complex and highly organized social structure. Each colony is centered around cooperation and efficient division of labor, with all members being divided into distinct castes that play specialized roles, from reproduction to foraging and defense.

Reproductive Castes

Queen and King: At the heart of every termite colony are the queen and king, whose mating produces thousands of eggs over their lifetimes, which drives the expansion of the population. Termite reproductives are long-lived, sometimes surviving for decades (Figure 3) (Figure 4).

Neotenic Reproductives: The king and the queen are the primary reproductive members of the colony, but when they die or when the colony expands, secondary reproductives called neotenics develop from workers or nymphs within the colony. These neotenics often inbreed within the colony to maintain or expand the population.

The Worker Caste

Workers are considered the “engine” of the colony, performing tasks that are central to its survival, including foraging for materials rich in cellulose, constructing and maintaining tunnels, caring for eggs and juveniles, and performing activities like corpse management that contribute to their social hygiene. Most workers are sterile, i.e., they lack the ability to reproduce (Figure 5). Workers engage in trophallaxis, a process of sharing food and gut symbionts with colony mates, especially those members (e.g., soldiers, reproductives, and juveniles) that cannot feed themselves. This mechanism ensures that the entire group benefits from nutrient acquisition and gaining a full complement of their gut microbiome.

The Soldier Caste

Soldiers in Eastern Subterranean Termite colonies serve as the primary line of defense against threats from predators and rival colonies. Although they make up only a small percentage of the colony (2–4%), their specialized anatomy and behavior make them critical to the colony’s survival. Soldiers are morphologically distinct from other castes. They possess heavily sclerotized (hardened) head capsules and powerful mandibles, which they use to slash into invaders (Figure 6). However, these oversized mandibles prevent them from feeding directly on wood and are therefore entirely dependent on receiving pre-digested food via trophallaxis from workers. Soldiers often seem to be strategically stationed at vulnerable points in the colony and on foraging trails. They may be found more frequently guarding tunnel entrances or around reproductive members.

Communication and Cooperation in the Colony

Coordinating activities within the termite colony requires sophisticated communication based on chemical communication between individuals. Chemical signals transmitted using pheromones regulate caste differentiation, reproductive status, and alarm responses. Additionally, antennal tapping and mutual grooming reinforce social cohesion and aid in resource sharing. Of unique note, termite soldiers will bang their heads on the ground to alert nearby workers of potential threats and to elicit defense responses from other nestmates.

Ecology & Microbiome

Why do They Thrive in North America?

Eastern Subterranean Termites are native to North America and thrive in many temperate climates around the world. Their natural range includes forests, where they play important roles in breaking down cellulose-rich materials like fallen logs. Their success, however, stems largely from their ability to live and forage underground, giving them access to food resources while avoiding environmental pressures and predators.

Their success in urban environments stems from a combination of their ability to exploit wood in human structures and their adaptability to soil-based habitats. Moisture, warm temperatures, and access to cellulose make urban environments ideal for colonization. Couple these factors with the ever-growing need for housing and cookie-cutter structural designs full of hidden pathways (cinder blocks, brick veneer, dirt-filled porches), and you get an ever-growing market of food – the eating is good.

Perfect Wood Destroyers

Termites are part of the insect order Blattodea (which also includes cockroaches) and have been feeding on wood (cellulose) since their origin around 150 million years ago. The uncanny efficiency with which the Eastern Subterranean Termite digests wood comes from a combination of physiological adaptations and the tight-knit symbiosis with their gut microbiome that they have evolved over millions of years:

The Gut Microbiome:

-

Eastern Subterranean Termites rely on a dense population of gut microorganisms, including bacteria and protozoa, to break down cellulose into simpler compounds like glucose – a sugar. These symbionts produce enzymes that break cellulose materials apart (through hydrolysis) and make it easier to digest!

-

Their hindgut (similar to your colon) serves as a fermentation chamber, where microbes convert cellulose into short-chain fatty acids, which termites absorb as an important energy source, and methane – yes, termites fart.

Endogenous Enzymes:

-

In addition to microbial help, Eastern Subterranean Termites produce enzymes in their salivary glands. These enzymes work together with microbial-produced enzymes, maximizing digestion efficiency and extraction of nutrients.

Efficient Resource Use:

-

To top things off, the complex and highly coordinated social structures of these termites are integral to the efficient breakdown of their wood-based diet that few other organisms can exploit.

-

They recycle nutrients within the colony by feeding on each other’s feces (coprophagy) and exchanging symbionts through trophallaxis. This ensures all individuals, especially juveniles and soldiers, maintain a functional gut microbiome.

Foraging & Swarming

Foraging

As mentioned above, Eastern Subterranean Termites feed exclusively on cellulose-based materials, and spend nearly their entire life underground – so how do they find this food? Well, put simply, they engage in random foraging behaviors through the soil, with groups emanating from the colony center. As they branch out they produce pheromones to communicate their location and are able to pick up on chemicals and odors produced by food sources that permeate through the soil. Should they hit a barrier they travel upwards, and upon leaving the moist soil they construct mud tubing which maintains moisture and provides protection for foraging termites. In fact, these tubes are one of the signs of termite infestation on structures, often traversing foundation walls to approach the wooden members of the structure (Figure 7). Upon finding a new food source for the colony, termites communicate this discovery and recruit fellow termites to begin exploiting this new resource. Depending on the size of the colony, Termites can forage across areas of up to ⅓ an acre and regularly travel up to 200 feet away from the nest. In fact, as colonies continue to grow, and in support of more effective foraging, satellite nests can form – creating a network of chambers and tunnels comprising a single massive colony.

Swarming

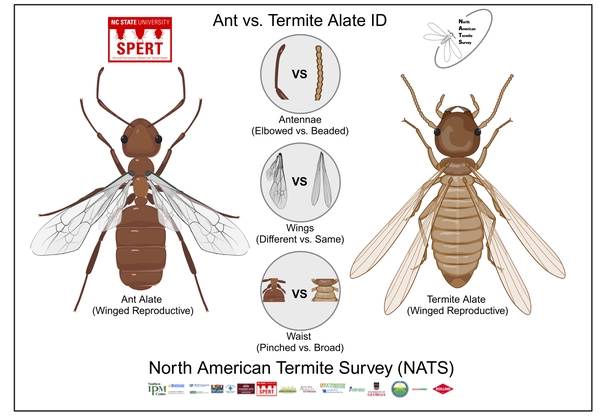

Swarming refers to the seasonal behavior of winged reproductives – alates – to be produced by a mature colony and take to the skies in order to have gene flow and find a mate. In North Carolina, Eastern Subterranean Termites typically swarm on warmer and gusty days (especially after a recent rain) from late Spring to late Summer. Swarming can even occur in early Spring on particularly warm days, or even later into the Fall, depending on weather conditions, colony size and maturity, and temperature. Essentially, you could possibly see swarmers at nearly any time of the year in NC, given the right conditions. Swarmers are typically seen outdoors, around stumps and coming out of infested trees, but are not necessarily a sign of structural infestation. However, they can occur indoors, and in this situation, it is most certainly a sign of active infestation. Oftentimes, termite and ant swarmers can be confused for one another, however, there are key differences to look for when telling these two insects apart (Figure 8):

-

Antenna: Bent vs. Straight – Ant swarmers have “elbowed” antennae, while termite swarmers have straight and beaded antennae.

-

Wings: Different vs. Same – Ant swarmers have two larger wings (front) and two smaller wings (hind), with termite swarmers having four wings of roughly the same size and shape.

-

Waist: Pinched vs. Broad – Ant swarmers have a pinched waist, while termite swarmers have a broad waist.

To learn more about swarming, and to understand the potential risks of swarming termites check out our publication: Termite Swarmers - What Do They Mean for You?

Risk to Structures

The Eastern Subterranean Termite is the greatest silent threat to built structures in North Carolina, often going unnoticed for years until serious damage has occurred. A colony of roughly 60,000 can consume 1 foot of 2x4 lumber in roughly 5 months, and while this may seem like a small amount it adds up quickly. Typically, serious structural damage takes between 3-8 years of ongoing feeding and infestation to occur. Across the U.S. annually it is estimated that termites cause over $5 billion in damages. The cost to individual residents could be up to $3,000 for treatment, and upwards of $38,000 in repair costs for well-established and overlooked infestations. As such, it is critical to take several steps to protect your structures and stay ahead of the termites:

-

Look for damage: Wood that sounds "hollow" when it is tapped with the handle of a screwdriver, or that is easily penetrated by a knife or screwdriver tip. Look for mud within the wood as an additional sign of termite activity rather than just water damage. If damage is found it is important to consider the treatment history of the property and contact a professional pest management service.

-

Look for tubes: As mentioned above, these termites will produce mud tubes to cross areas above the soil in pursuit of food (Figure 7). Look for these along foundation walls, behind siding, in basements, and even in the crawlspace. If found, break them open and see if live termites are moving about. The absence of termites in a broken tube doesn’t mean they aren’t feeding on the house. Tubes can sometimes be abandoned, and if found the treatment history of the house should be considered and a professional pest management service should be contacted.

-

Annual inspection: It is highly recommended to have your structure inspected annually for termite activity and evidence by a professional pest management service. They are trained experts at identifying termite evidence, and should evidence be found, are the only reliable option for effective management.

Many residents and homeowners worry over the potential risk of termites, and the damage they can cause. While they are a serious concern across NC, we have not given you the knowledge and steps to monitor your home, know the enemy, and trust the professionals.

Publication date: Jan. 22, 2025

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.