Introduction

Black shank is among the most destructive and widespread of all tobacco diseases in North Carolina. Black shank first appeared in the United States in 1915 and was first reported in North Carolina in Forsyth County in 1931. Currently, black shank can be found in every North Carolina county that grows flue-cured tobacco. Reducing the economical impact of black shank in tobacco requires an integrated management approach in fields with high disease pressure. Improved breeding efforts and chemical control measures have added more management tools for this disease.

Pathogen

Black shank is caused by soil-borne oomycete (water mold or fungal-like organism), Phytophthora nicotianae (syn. Phytophthora parasitica). This species infects over 255 genera in 90 families, including Nicotiana (tobacco). Tobacco varieties may exhibit varying host resistance to different races of the pathogen. Races 0, 1, and 3 have been reported in North Carolina, with 0 and 1 as the most prevalent races. More information about resistance to these races can be found in the ‘Disease Management’ section below.

Symptoms

Phytophthora nicotianae may cause black shank in high humidity or wet conditions and warm temperatures. Black shank can affect any part of the tobacco plant at any growth stage. The most common symptoms associated with P. nicotianae are root and crown rot characterized by rapid yellowing, wilting of leaves, and eventually plant death (Figure 1 and Figure 2). At the ground level, a dark brown to black lesion often appears on the stem. When the lower stem is cut in half longways, the lower stem and crown often show blackened pith with distinct disks and white hyphae (Figure 3). Stalk disking and blackening is only of diagnostic value in conjunction with other observations, as disking may be caused by other factors (other fungal infections, lightning strikes, etc.). In severe cases and periods of prolonged drought, wilting symptoms and pith necrosis are followed by death of the entire plant.

Diseases With Similar Symptoms

Fusarium Wilt (Fusarium spp., Figure 5)

This pathogen can produce yellowing and wilting of leaves, and browning of the pith. The causal organism of Fusarium wilt is a weak pathogen, and often requires other damages to the roots, such as poor environmental conditions or nematode infestations.

Granville Wilt (Ralstonia solanacearum, Figure 6)

This pathogen causes yellowing and wilting of plants, but starts as one-sided wilting. When stems are cut open, brown, water-soaked lesions are usually visible within the pith (Figure 7). Bacterial streaming can also be observed when a cut section of diseased stem is placed into a cup of room-temperature water.

Disease Cycle

Phytophthora nicotianae may reproduce asexually and sexually, and cause infection more than once per season (polycyclic). Asexual reproductive structures, chlamydospores, sporangia, or zoospores can all germinate to form hyphae on and within affected tissues. Sexual reproduction requires two mating types (A1 and A2) to form thick-walled oospores. Sexual spores are not thought to be the primary survival structure or initiate infections, as only one mating type is usually found in the same field. While wounds are not required for host infection, they do favor more rapid disease build-up.

When soil conditions are not conducive for infection, thick-walled chlamydospores (survival structures) form and can survive from 4 to 6 years in soil. When conditions are favorable for infection, the chlamydospores germinate to produce germ tubes, which may infect roots directly, or more often form sporangia that produce swimming zoospores. Zoospores swim toward roots, encysts on the root’s surface, and produces a germ tube which penetrates the outer cell layer of the root. Where sexual reproduction occurs, plants may become infected by oospores through the roots. As the pathogen spreads through the roots, limited nutrient and water movement to the stem causes wilting, chlorosis, and eventual death of the plant.

As long as conditions remain favorable, a new generation of motile spores is produced every 72 hours. This pathogen may also cause a leaf spot from infested soil that splashes onto the leaves during rain events. Images of this pathogen and its life cycle can be found at the Tobacco Diseases website.

Disease Management

It is important to use an integrated management approach, which uses resistant varieties, cultural practices, chemical and biological controls to reduce damages from black shank long term. An integrated management approach also reduces the risk of developing populations (race shifts) of the pathogen, P. nicotianae, that overcome resistant varieties and current fungicides.

Resistant Varieties

There are different sources of resistance used in available varieties: polygenic resistance, Ph gene, and Wz gene. Polygenic resistance has been the predominant form of resistance for many years. It is effective in varying degrees against both race 0 and race 1 of the black shank pathogen.

The Ph gene from Tex-Mex tobacco (Nicotiana plumbaginifolia) has been incorporated into a large number of flue-cured tobacco cultivars to provide resistance against races 0 and 3 of P. nicotianae. Varieties with the Ph gene may vary in their resistance to race 1 depending on the polygenic resistance that is in their heritage. Widespread planting of cultivars with the Ph gene has been linked to the shift in the P. nicotianae population in US (including North Carolina) tobacco fields from mostly race 0 to mostly race 1. Changes in race populations are being monitored.

The Wz gene confers resistance to race 0 and race 1. Commercially available varieties with the Wz gene include CC35, NC960, and NC 1226. Recent studies have demonstrated that P. nicotianae populations can overcome resistance when challenged by repeated plantings of tobacco containing this gene. Rotation of host resistance traits and use of fungicides may help prevent fungicide-resistant pathogen populations from developing.

Selecting resistant varieties is the most economical management strategy of this pathogen for tobacco growers. Though complete resistance to black shank is not available with recent race shifts, tobacco varieties with high levels of resistance to black shank disease should be prioritized and used in combination with other management practices. See 'Integrated Pest Management Approaches' section below.

Cultural Practices

Exclusion and Sanitation.

The pathogen can be moved in infested soil via equipment, vehicles, tools, or shoes that have entered the field. Equipment from fields with black shank should be sanitized before moving to unaffected fields. Workers should also sanitize shoes after working in infected fields. Working in fields with known histories of black shank last will reduce time and effort needed for sanitation of equipment.

Field sanitation is an important step in managing this disease and reducing its spread. Destroying stalks and roots quickly after harvest will help reduce inoculum. Contaminated irrigation or runoff water may also aid in its movement within a field or from one field to another. Improving drainage in areas where water pools can reduce the environmental suitability of the soil.

Crop Rotation.

Phytophthora nicotianae mainly affects ornamental species, so any other field crops can be used in rotation to help reduce inoculum in the soil. Longer rotations will reduce inoculum more than shorter rotations.

Chemical Control

Fungicides may help reduce disease incidence in fields with disease. Early applications (transplant water, surface applied, or soil incorporated) are the most effective in reducing disease in tobacco fields, and repeated applications may be necessary in fields with high disease pressure. In fields with high disease pressure, fungicides in combination with the selection of a resistant variety and good cultural practices may be required to manage this disease. See 2024 black shank fungicide trial.

Integrated Pest Management - Resistant varieties & Chemical controls

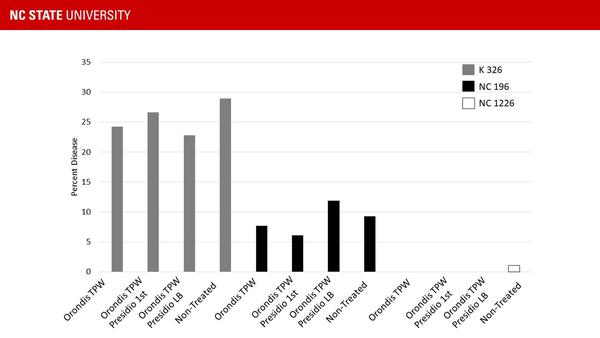

In 2019 trials, varieties with different host resistance (low [K326], moderate [NC 196], and high [NC 1226]) were combined with fungicide programs (Orondis in transplant water [TPW], Orondis TPW followed by Presidio at 1st cultivation [1st], or Orondis TPW followed by Presidio at layby [LB]). While variety provided the greatest level of control, disease was still observed in treatments with no fungicides (Figure 8). Adding a fungicide to a highly resistant variety may help reduce pathogen populations that may be able to colonize new host resistance traits.

Useful Resources

The NC State University Plant Disease and Insect Clinic provides diagnostics and control recommendations.

The NC State Extension Plant Pathology Portal provides information on crop disease management.

The North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual provides pesticide information for common diseases of North Carolina. The manual recommendations do not replace those described on the pesticide label, and the label must be followed.

The American Phytopathological Society provides a complete review about black shank disease in tobacco.

The Tobacco Diseases Information page, created by the Shew lab at NC State University, provides in depth information on this and other tobacco diseases found in North Carolina.

For assistance with a specific problem, contact your local N.C. Cooperative Extension agent.

Note on Recommendations

Recommendations of specific chemicals are based upon information on the manufacturer's label and performance in a limited number of trials. Because environmental conditions and methods of application by growers may vary widely, performance of the chemical will not always conform to the safety and pest control standards indicated by experimental data. All recommendations for pesticide use were legal at the time of publication, but the status of registration and use patterns are subject to change by actions of state and federal regulatory agencies.

Publication date: Oct. 20, 2017

Reviewed/Revised: Dec. 1, 2024

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.

NC Cooperative Extension prohíbe la discriminación por raza, color, nacionalidad, edad, sexo (incluyendo el embarazo), discapacidad, religión, orientación sexual, identidad de género, información genética, afiliación política, y estatus de veteran.

Recommendations for the use of agricultural chemicals are included in this publication as a convenience to the reader. The use of brand names and any mention or listing of commercial products or services in this publication does not imply endorsement by NC State University or N.C. A&T State University nor discrimination against similar products or services not mentioned. Individuals who use agricultural chemicals are responsible for ensuring that the intended use complies with current regulations and conforms to the product label. Be sure to obtain current information about usage regulations and examine a current product label before applying any chemical. For assistance, contact your local N.C. Cooperative Extension county center.

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.