Introduction

This guide focuses primarily on North Carolina examples of local and regional governments and community advocates creating innovative local food economies. We developed the guide to serve as a tool that connects planners, economic developers, and other local government officials and administrators with resources for increasing the development of local food economies. The guide has three sections:

- Planning and Land Use for Local Food Economies examines planning, land use, and zoning issues that directly affect farms, food businesses, and other contributors to the local food economy.

- Economic and Community Development for Local Food Economies discusses strategies for the retention, creation, expansion, and recruitment of farm and food businesses.

- Collaborating for Growth offers recommendations for nontraditional partnerships and inclusive planning strategies that bring together disparate elements of local food economies.

Local Food Economies in North Carolina

A local food economy is the system within which food is produced, distributed, and purchased within the same area (Figure 1). Developing a local food economy has been recognized as a way to revitalize traditional agricultural communities and energize urban, periurban, and rural landscapes alike.

Support for these systems includes the creation, retention, expansion, and recruitment of farms and food-related businesses in a town, county, or region. These actions make a positive impact on a variety of industries, including production, processing, storage, transportation, distribution, and wholesale and retail sales entities.

Developing local food economies is an important tool for protecting farmland and natural resources, and maximizing a community’s environmental, social, and economic health (Garrett and Feenstra, 1995).

|

The range in sizes and types of businesses in a local food system diversifies the economic base, a characteristic of a resilient economy—one that can prevent, withstand, and quickly recover from major disruptions (U.S. Economic Development Administration, 2016). Local food economies are also self-regenerating, with businesses linked along the supply chain purchasing local inputs and selling to local consumers. |

For the purposes of this document, local is defined as food that is grown, raised, caught, and consumed within North Carolina; local agencies may adopt a narrower definition to meet their requirements and interests.

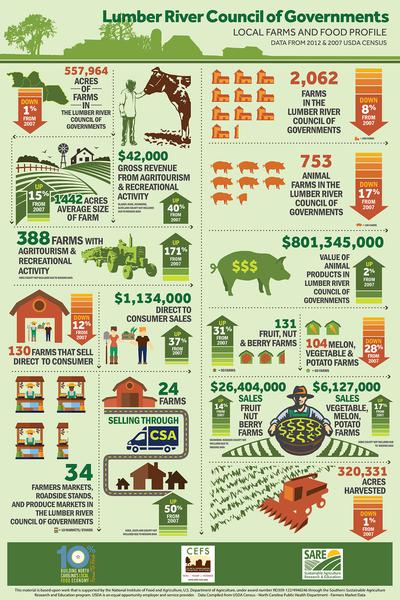

Agriculture is one of North Carolina’s top industries, consistently ranking first or second, and bringing in more than $84 billion to the state’s economy (Figure 2). Agriculture and associated industries are responsible for over one-sixth of the state’s labor and income, and North Carolina ranks eighth in the nation for agricultural outputs (Shore, 2016).

Local governments have unique opportunities to work with the many experts within the food system—including North Carolina Cooperative Extension agents, Soil and Water Conservation District staff and boards, planners, economic developers, and community groups—to promote a sustainable food system. There are many options for flexible local ordinances and incentives, citizen-led food councils, and small business development programs that rely on local governments’ existing partners.

As local governments begin to involve themselves in the work of developing local food economies, the process can create stronger partnerships with existing agencies and new nontraditional partnerships that help ensure the health and economic vitality of both rural and urban areas.

Agricultural Economic Development in North Carolina

Agricultural economic development (AED) addresses the creation, retention, expansion, and recruitment of agricultural and food-related businesses in a town, county, or region. AED projects are planned and implemented in conjunction with farmland preservation planning, strategic planning, and traditional economic development (CEFS, 2016a).

Agricultural economic development can provide important institutional support for local food systems, and can help connect farmers and food entrepreneurs to resources at the local level. Communities are using a number of different strategies to incorporate the goals of AED into their strategic and comprehensive plans, and taking steps to create policies that support innovative AED programs:

- Create a Farmland Protection Plan and its associated advisory board.

- Include a food system goal in the strategic plan and assign resources.

- Adopt a specific policy statement through planning, such as inclusion of specific regulations in a UDO (unified development ordinance) or individual ordinances.

- Establish a department or division with this focus and allot funds.

- Incorporate AED into the economic development strategy or plan.

- Establish cross-sector partnerships, such as public-private partnerships or nonprofits, focused on this work—typically through an MOU (memorandum of understanding) with other partners.

Currently, there are three agricultural economic developers in the state, funded and authorized in different ways, reflecting the many factors that inform decisions about establishing AED. There are many other governments researching how to establish and fund AED at the local and regional government levels.

|

Mark Williams, Henderson County This position was created as part of the comprehensive planning process, which emphasized the importance of the apple industry in Henderson County, and was county-funded. Mr. Williams directed the recruitment of Bold Rock Hard Cider company to Henderson County as a new market for the apple industry. Dawn Jordan, Polk County Ms. Jordan works in the first county to have an AED, a position created in 2011 in response to a land-use planning campaign which aimed to balance preservation of farmland and natural resources with second-home and tourism development. The position works closely with small and mid-scale farmers, market gardens, and community advocates of local food systems. Mike Ortosky, Orange County Orange County originally created a half-time position to support the operations of two county-supported incubators—a farm incubator and a kitchen incubator. Subsequently the position was expanded to full-time and now manages a grant program for food and farm entrepreneurs, among other activities. Mr. Ortosky focuses on creating new markets for farmers to encourage their continued farmland use, and on preservation and recruitment of additional food businesses. |

Research Overview on Local Foods

A growing body of research links local food systems to a variety of positive economic and health-related outcomes. Researchers have found that supply chains linking local production to local consumption generate greater revenues for producers, with net income ranging from equal to more than seven times the revenue gained from conventional national or global supply chains (King et al., 2010). Local food systems can also reduce farmland loss by creating opportunities for the next generation of farm owners.

The economic benefits extend to the broader community, with numerous studies indicating that food produced and consumed locally creates more economic activity in an area than does comparable food produced and imported from a nonlocal source (Enshayan, 2008; Henneberry, Whitaker, and Agustini, 2009; Lev, Brewer, and Stevenson, 2003; Otto and Varner, 2005; Sonntag, 2008). The impacts of local food systems on farm and community businesses (through increased revenues and employment) come from two sources: the transactions that occur between local consumers and local farms and the effects of keeping local dollars in the community to be spent at other businesses.

|

CEFS published a research overview on local food systems with N.C. Cooperative Extension, an annotated bibliography, and a literature review on the relationship between economic development and local food systems in 2016. Research Overview: Local Food Systems, Clarifying Current Research (LF-013) |

The economic impacts are further enhanced when inputs to the farm come from local sources and the farm outputs are used by local food entrepreneurs for value-added products. Researchers who investigate local food systems use the tools of economic development professionals, including IMPLAN, to estimate economic impacts. The USDA’s Toolkit for Calculating the Economic Impact of Local Foods is the first national analysis tool for examining how local food businesses and projects contribute to economic impact.

Local food systems can also improve the health of community members. Epidemiological researchers have found correlations between higher levels of direct-to-consumer farm sales and lower levels of mortality, obesity, and diabetes (Ahern, Brown, and Dukas, 2011; Salois, 2011). These findings supplement qualitative studies that have linked more direct connections to food (via direct contact with the farmers who produce the food, such as through a farmers market or a consumer-supported agriculture buying program, via participation in a community garden, or living in the household of a community gardener) to improvements in eating behaviors (Alaimo et al. 2008) and enhanced social activity and civic engagement (Saldivar-Tanaka and Krasny, 2004).

The Center for Environmental Farming Systems

The Center for Environmental Farming Systems (CEFS) develops and promotes just and equitable food and farming systems that conserve natural resources, strengthen communities, improve health outcomes, and provide economic opportunities in North Carolina and beyond. CEFS is a partnership of NC State University, NC Agricultural and Technical State University, and the NC Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (NCDA&CS). Established in 1994, CEFS is one of the nation’s most important centers for research, extension, and education in sustainable agriculture and community-based food systems.

CEFS is recognized as a national and international leader in the local foods movement and is celebrated for its work in building consensus around policies, programs, and actions that facilitate a vibrant local food economy. In 2008 and 2009, CEFS convened hundreds of food system stakeholders across the state in regional meetings, which concluded with a statewide summit, to develop “game changer” strategies to transform North Carolina’s food system. These strategies, and other outcomes of the process, are detailed in From Farm to Fork: Building a Sustainable Local Food Economy in North Carolina, a comprehensive guide to statewide action (Curtis et al., 2010).

CEFS-affiliated faculty, researchers, and graduate students conduct sustainable agriculture research at the CEFS 2,000-acre Field Research and Outreach Facility at Cherry Research Farm in Goldsboro, North Carolina. In addition to the Research Farm, CEFS has the following focus areas: Food System Initiatives, Extension and Outreach, Academics and Education, and Youth. CEFS works through collaborative, interdisciplinary research, extension, and education towards its vision: a future of vibrant farms, resilient ecosystems, strong communities, healthy people, and thriving local economies.

Planning and Land Use for Local Food Economies

Uniting Planners and Communities through Local Food Systems

For the past several decades, traditional planning approaches rarely accounted for food systems. As the American Planning Association (APA) has noted (2007), several factors affected this decision, including the perceived gap between the built environment and food systems, a general feeling that the food system was working without the need for interference and a perception that planning’s emphasis on public goods and infrastructure didn’t include food production or consumption.

In recent years, however, planners have become more interested in food systems at the local, regional, and national levels. Several factors have heightened interest in food system planning, including the need for emergency planning for crisis situations, health and wellness initiatives directed at obesity, increases in food insecurity and hunger, consumer and community interest in knowing the origin of food, and the growing influence of food policy councils across the country.

Planners are uniquely positioned to support initiatives that increase access to healthy and local foods while supporting farmers and food businesses. While food policy councils are effective community advocates and agricultural advisory boards of all kinds can provide specific resources to local governments, planners have the capacity and skills needed to help communities address long-term, big-picture food system goals. As the APA acknowledges, planners are trained in “the analysis of the land use and spatial dimensions of communities, externalities and hidden costs of potential policy decisions, interdisciplinary perspectives on community systems like the food system, and ways to link new goals like community food systems into sustainable and healthy community goals” (APA Food Systems Planning Committee, 2008).

These are valuable skills for groups working on local food initiatives, which are often composed of farmers, community members, urban gardeners, and others whose experience in government is limited. Working with such groups provides planners an opportunity to use their skills at a systems-planning level while also connecting one-on-one with citizens across a broad range of interests.

Planning for agriculture at the local and regional levels can have positive impacts across a broad range of planning goals:

- Meeting community requests for food access and farmer support

- Revitalizing downtown areas with farmers markets and food businesses

- Providing new uses for vacant land

- Increasing community health through access to food

- Protecting farmland and managing increased demands for development

- Improving pollution and water quality through working lands protection

- Capitalizing on economic benefits through increased markets for regional products

- Building infrastructure, such as water and sewer and broadband, and infrastructure business opportunities, such as cold storage or distribution

- Supporting other natural, built, and human resource development associated with long-term strategies for community success (Hodgson, 2012; APA, 2007)

Innovation in Planning and Economic Development

Integrating food systems and planning provides innovative opportunities at the leading edge of the planning sector, especially in regionalism, multidisciplinary planning, and applied technology. Regionalism, an economic development and planning approach that considers needs across a defined geographic area that includes multiple units of local government, allows for long-term market-based partnerships as well as coordinated strategies for development (Association of Wisconsin Regional Planning Commissions, 2014). By its nature, agriculture is a regional enterprise and offers communities a way to work together on important development issues. Food systems also bring together a diverse group of stakeholders from multiple industries and with varying motivations (see the “Collaborating for Growth” section of this guide). This allows planners to use multiple approaches, particularly from the economic development, health, and design fields, to solve complex problems that affect every population within a community. Food systems planning and development is at the leading edge of innovation in public service, offering multiple ways for unique solutions to be implemented. Technological solutions—from cloud-based farm data management, to app-based food ordering, to gleaning matches between farms and food banks—provide capacity and capability to find real-world solutions.

In this section, we discuss approaches that planners can use to outline long-term goals for food systems within a community, as well as specific policy tools—such as those related to farmland preservation and zoning. Additional resources can be found through the American Planning Association and through the SUNY Buffalo Growing Food Connections Project, which brings together urban and regional planning resources with local food systems research and implementation projects.

*Authors’ note: Pending a final decision, we prepared this guide without accounting for the proposed changes to planning and development regulation in the NC General Assembly Local Government Regulatory Reform Bill. House Bill 548 has been under discussion and review since 2015, and was referred to committee at the end of the June 2016 session (see the UNC School of Government analysis of the bill’s various changes to regulatory authority). Planners and developers should monitor changes created by this bill, as the changes will affect many of the regulatory and enforcement capacities of local governments. Many of these changes could affect how agriculture and food systems are integrated into ordinances and planning strategies.

Calculating Economic Impact

Central to the argument that investment in a local food system will generate economic dividends for the local economy is the idea that food dollars spent locally will experience a multiplier effect as local farmers, in turn, purchase intermediate inputs, labor, and capital from within the localized economy (O’Hara and Pirog, 2013).

Though this theory is fundamental to the ongoing conversation among economic developers and local food advocates, available findings are difficult to generalize across a diverse set of communities and economies. For more information about recent research into the economic impact of local foods, please see the “Economic and Community Development” section of this guide.

Common Topics: Community Gardens, Urban Agriculture, Roadside Stands and Mobile Markets, and Farmers Markets

Community Gardens

A community garden is defined as any public or private facility used for the cultivation of edible and ornamental plants by more than one person (Davidson and Dolnick, 2004). Careful planning is important to locate community gardens outside environmentally sensitive areas and within walking distance of local residents. Advocates also need to consider many issues, including zoning, land ownership for long-term availability of the garden site, business licenses required for selling of produce, and emerging federal health and safety laws on agricultural products.

Community gardens in low-income areas can be especially valuable as they provide lower-cost fresh and healthy food to residents who may not have access to a grocery store, cannot afford high prices for fresh produce, and have difficulty getting to a farmers market. Community gardens may place less strain on local government budgets and capacities than more difficult solutions to food access, such as supermarket recruitment or development of appropriate parcels of land for grocery stores.

In North Carolina, many citizen groups, nonprofit organizations, and state agencies have collaborated to promote and establish community gardens. Community gardens often benefit from state agencies and from the experience of leaders and staff in county and municipal parks and recreation offices, local Extension centers, health departments, community organizations, and local schools. Local garden clubs can provide key volunteers and expertise to community garden efforts and often take the lead on implementing these projects.

For example, NC Community Garden Partners began with a partnership between the NC Division of Public Health, N.C. Cooperative Extension, and community garden advocates across the state. Together the partners have created a website, social media site, gardening primer, and community garden listserv, and the group hosts regular meetings and workgroups to foster its mission of increasing the number of successful and sustainable community gardens in North Carolina.

Another promising initiative was started in 2011, when the NC Recreation and Parks Association partnered with Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina to establish Nourishing NC, an initiative with the objective of establishing a community garden in every county in North Carolina by 2013. As of 2016, only seven counties do not have a reported community garden on the list. This initiative was one of the “game changer” ideas resulting from the 2010 CEFS Farm to Fork initiative.

|

Additional Resources for Community Gardens

|

Urban Agriculture

Urban farms within cities can be small in acreage, and the food can either be shared or sold. Some farms set up a formal sales operation to distribute wholesale to restaurants, while others sell through direct-to-consumer channels—such as farmers markets (often on site) or through a community-supported agriculture (CSA) system.

Urban farms provide more than just working green space for city dwellers. Urban farms can also be employment and value-added entrepreneurial activities for residents and municipal revenue sources based on the sales tax levied on farm products sold there (Brown and Carter, 2003). Will Allen’s Growing Power model (growingpower.org), which combines urban farming with training and technical assistance to community members to learn sustainable practices for growing, processing, marketing, and distributing food, has been adopted in several urban centers and continues to spread (Growing Power Inc., 2014).

Urban farms offer many benefits, such as access to local fresh food, jobs, and educational opportunities. A study conducted in 2008 highlighted the benefits of middle- to large-scale urban agriculture and provided urban planners with six existing models of urban farms across the country (Myers, 2008). Bio-intensive production methods, often used in land-scarce urban settings, offer a range of benefits, including a more than 50 percent reduction in water usage and purchased fertilizers, a 100 percent increase in soil fertility, and production of two to six times more food compared to conventional methods (Jeavons, 2001; Jeavons, 2002). Some farm products sold in their original state by producers may be exempt from sales tax, depending on the state and the size of the farm. In North Carolina, this exemption was repealed and amended in 2014, and farmers must meet particular requirements to be exempt from sales tax (N.C. Gen. Stat. § 105-164.13; NC Department of Revenue, 2014).

In the past few years, the issue of urban chickens has been brought up in many town meetings, with advocates noting the benefits of fresh eggs, free natural fertilizer, and natural pest control (Edwards and Carver, 2008) (Figure 4). As of 2016, at least 31 NC municipalities and counties allowed “backyard chickens.” In some cities, groups host events to promote backyard chickens as agritourism, such as Raleigh’s annual “Tour D’Coop” (2017). Local governments can examine whether chickens and other livestock are allowed under their zoning, animal control, or other applicable ordinances. Several factors should be considered, including whether to allow roosters, the number of chickens, whether to allow commercial sales of eggs or meat, distance from dwellings, amount of land required, enclosure of the house and run area, and sanitation. State and federal regulations also apply to the processing and sale of meat and eggs.

One example of urban farm permissions is in the City of Winston-Salem, where the planning department allowed urban farm activities in all residential districts in the city after urban agriculture was approved as a primary strategy in the Legacy 2030 Comprehensive Plan for Winston-Salem and Forsyth County. The department developed a community guide to approving urban agriculture projects and later directed its staff to complete a Food Access Report for the City, outlining needs and barriers for access in all communities.

|

Additional Resources for Urban Gardens

|

Roadside Stands and Mobile Markets

In many rural agricultural areas and in the urban areas that they border, farmers may choose to sell directly to consumers by parking their trucks loaded with fresh produce alongside the road, usually with a sign advertising fresh produce for sale. This type of mobile market is usually allowed in county ordinances related to agriculture. Due to the increase in consumer demand for fresh local food, many cities and towns in North Carolina also allow mobile markets in downtown areas, especially if a farmers market has not been established. Some municipalities allow outdoor fresh produce stands to be set up in empty parking lots within the town limits during the growing season.

Depending on whether or not the roadside stand is located within a county jurisdiction or municipality, there are a number of questions to consider relating to roadside stands and mobile markets. Is a vendor’s license or permit required for roadside stands? Do sign ordinances apply? Is the roadside stand located on the property where the products were produced?

A stand may be allowed under county zoning if it is part of the farm operation and the items sold are produced on that farm. Counties and municipalities should consider amending their zoning ordinances to allow for the retail sale of produce and agricultural products either on the farm where they are produced or at off-site farm stands or mobile produce trucks. Ordinances developed to allow the sale of farm produce at off-site locations allow growers to benefit from higher population densities and traffic volumes that may exist some distance away from the farm.

Landowners who participate in Enhanced Voluntary Agricultural District (EVAD) programs can sell products on land enrolled in an EVAD—even if the products are not produced on site—and receive up to 25 percent of gross sales, while still having those sales fall under the bona fide farm purpose exemption from county zoning. Additionally, the production of any nonfarm product on land enrolled in an EVAD program recognized as a "Goodness Grows in North Carolina" product is considered a bona fide farm purpose that may also be exempt from county zoning: NC Gen. Stat. § 106‑743.4(a). An example of a nonfarm product is peanut butter produced from peanuts originating off-site from other farming operations.

Communities may allow some flexibility for growers who need to bring in and sell agricultural products from other growers in the same area. This opportunity allows growers to generate additional income and offer a more diverse range of local products. An allowance of collective sales from local farmers is not the same as resell practices that bring food in from outside the region.

|

Additional Resources for Roadside Stands and Mobile Markets

|

Farmers Markets

Farmers markets provide an opportunity for urban and rural residents to purchase fresh local foods close to home (Figure 5). They can increase the incomes of local farmers and at businesses adjacent to the markets and bring tourism dollars to downtown areas. A farmers market has a multiplier effect on the local economy because more money stays in the community and is recirculated.

In one studied community, for every $100 spent at the local farmers market, $62 was recirculated—for a total local impact of $162. In comparison, for every $100 spent at an average grocery store, only $25 is respent locally (Sonntag, 2008).

North Carolina now has well over 200 farmers markets (NCDA&CS, 2017). Counties and municipalities can revise their land-use policies to allow existing markets and promote new ones by defining and listing farmers markets as permitted uses within their zoning ordinances. Unless farmers markets are specified as allowed in the zoning regulations, permitting a farmers market to be established or remain in use could be considered a violation of the zoning ordinances.

Governments can also promote farmers markets by providing a site with shade and plumbing, renting space to the farmers market for a nominal fee (a $1 fee is often used), helping advertise the market, providing funds for a market manager, and making sure the markets are accessible via public transportation. Farmers market organizations often work with local governments to provide the administrative framework (such as rules, regulations, membership, and financial recordkeeping) and insurance (Goforth, 2010).

Growers-only markets (those that restrict sales only to items produced by the sellers) do more to support developing local food economies than markets that allow nonlocal produce to be sold alongside that of local producers. These nonlocal markets can confuse and anger consumers, who visit markets to support local agriculture. And markets that allow nonlocal produce can anger farmers, who may perceive that these ”local” markets are being advertised inaccurately.

A number of NC farmers markets are working to allow the use of electronic benefit transfer (EBT) cards (formerly Food Stamps) that are issued to NC Food and Nutrition Services Program participants. This increases the availability of fresh local food to people with low incomes, brings new customers to the markets, and increases sales for farmers. Currently, at least 53 NC farmers markets or individual farmers market vendors accept EBT cards.

|

Additional Resources for Farmers Markets

|

Comprehensive and Strategic Plans

Elected officials in county and city governments rely on community input and comprehensive land-use plans to make decisions regulating development and use of public and private lands. The plans guide a community’s growth, as well as the enactment and amendment of zoning and other ordinances. Through comprehensive plans, residents work together to create a future that considers the region’s prosperity and well-being. Agriculture should be included because it is a key contributor to the local economy and community health and because farmland, forestland, and horticultural lands can provide several other benefits to a community, including open space and wildlife habitat.

Many communities across the country are including sustainable, local foods in their regions’ long-term plans. The impetus for food system planning often begins with municipal, county, regional, or state food policy councils that engage with government officials, conduct food system assessments, and make recommendations based on the findings. Food policy councils and food system assessments are discussed in more detail later in this document.

In North Carolina, the NC Association of Regional Councils of Government has included small-scale agriculture and food system development in its NC Tomorrow Comprehensive Plan. Food systems meet the requirements of several guiding standards and principles for comprehensive planning, including U.S. Economic Development Administration Investment Priorities and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Livability Principles for such practices as environmentally sustainable development, valuing communities and neighborhoods, enhancing economic competitiveness, fostering resilience and regional successes, and increasing multidisciplinary collaboration (NC Association of Regional Councils of Government, 2016).

Additionally, the Piedmont Triad Regional Council (covering 12 counties) recently worked with the CEFS Community Food Strategies team to conduct regional planning and visioning for a collaborative approach to the local food economy (CEFS, 2016b). Piedmont Together, the regional initiative to explore development opportunities, focused its food system work on examining networks of aggregation and distribution hubs (Walker, 2014) and farm incubator projects (Piedmont Together, 2014).

Citizen input and long-term strategic planning are important to the overall success of these efforts. The effectiveness of farmland protection planning is enhanced when farmers are encouraged and given concrete opportunities to participate in planning. An important consideration when creating comprehensive plans is to budget sufficient funds to employ staff to actually implement the plan. Farmland protection plans can also be included or referenced in regional, county, and municipal comprehensive plans.

|

Additional Resources for Comprehensive and Strategic Plans

|

Farmland Preservation Planning and Tools

Farmland protection initiatives protect farmland, farmland-dependent businesses, and employment in these businesses. Agriculture and agribusiness are North Carolina’s leading industries, producing 20 percent of the state’s income and employing 17 percent of the state’s workforce (NC Agricultural Development and Farmland Preservation Trust Fund, 2016). Protecting farmland means protecting the economic and social vitality of NC communities.

Farmland preservation is vitally important for maintaining the appropriate land on which to grow food. North Carolina ranks as one of the states with the greatest loss of farms and farmland, with 2,695 farmers and 100,000 acres lost between 2007 and 2012 (NCDA&CS, 2014).

The average age of a farmer in North Carolina is 59, and the aging of farmers increases the likelihood that more acreage will transition from farming to development in the next decade. This loss of farmland represents a loss of cultural history, a loss of knowledge of farming techniques and practices, and a loss of economic opportunity in rural and urban areas.

The businesses that support local farms and that provide employment are also threatened, including traditional agricultural supply companies, associated businesses such as fuel suppliers and fertilizer dealers, and food processing and distribution companies.

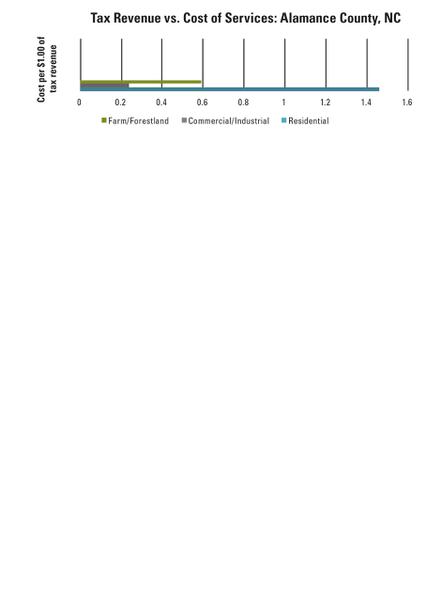

Another important economic factor for county and municipal governments to consider is the cost of services for housing developments versus farms. When a new housing development moves into what was once farmland, counties and cities must build infrastructure in the form of roads, schools, and water and sewer, and provide services such as fire, police, and emergency medical services. A number of studies in NC counties indicate that residential properties can cost counties more in needed services than the properties provide in revenue, while farms and forestlands pay more taxes than the services they require (Farmland Information Center, 2010).

For example, Figure 6 shows that for every dollar of revenue that Alamance County collected in 2010, the costs of providing services to various types of properties were as follows: residential ($1.46), commercial/industrial ($0.23) and farm/forestland ($0.59) (Farmland Information Center, 2010). These results do not mean that local governments should not allow development, but they do indicate the importance of balancing residential development with farms and forestlands.

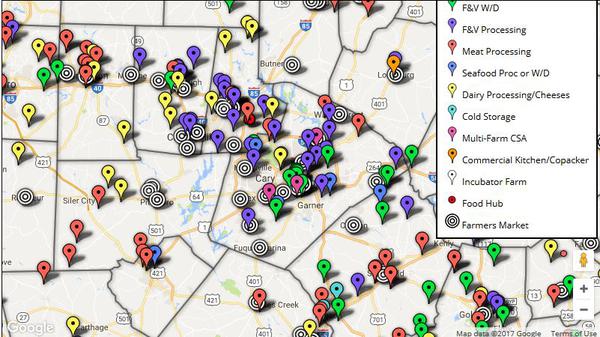

Counties and municipalities can contribute to protecting the future of working lands in agriculture and forestry by developing long-term plans that use tools to address community food issues and needs. A variety of existing tools are available for municipal and county governments working to conserve working farms and forests (Figure 7).

Some tools local governments may want to consider are cost-share programs, right-to-farm laws, purchase of development rights, present-use value taxation, agritourism, funding from federal and state programs, and technical assistance through the N.C. Cooperative Extension, NC Soil and Water Conservation Districts, and universities and colleges across the state (NC Department of Environmental Quality, 2015). The following sections provide an overview of farmland protection tools and county and municipal ordinances that can be used to protect working farmlands.

|

Additional Resources for Farmland Preservation Planning and Tools

|

Farmland Protection Plans and Funding

Farmland protection plans preserve farmland by identifying the extent and type of agricultural activity in a county and making recommendations on how to protect working farmlands. These plans can be useful guides for local governments when considering future development, and elements of the plans may be referenced or incorporated directly into county and municipal comprehensive plans, as noted previously. As of 2016, 50 of 100 NC counties had developed countywide farmland protection plans (NCDA&CS, 2017b, 2017c).

Voluntary Agricultural District advisory boards, which are formed from the enactment of Voluntary Agricultural District ordinances, can take the lead in developing farmland protection plans and inform government officials and citizens about the benefits of farmland protection and local food systems. These boards can be responsible for implementing action items in a plan.

For example, Durham County’s Farmland Protection Advisory Board has co-sponsored workshops on local and direct marketing opportunities for farmers, grant and cost-share opportunities, and ways to lower tax rates through the present-use taxation program (discussed later in this guide under “Present-Use Value Programs”). The Board works closely with the Durham Soil and Water Conservation District and the Piedmont Conservation Council to pursue other market opportunities. Chatham County’s plan addresses farmland preservation and agricultural economic development issues, and it includes recommendations for the county to promote farmer access to wholesale and retail markets and to create a program to retain and recruit farmers.

The Agricultural Development and Farmland Preservation Enabling Act was amended in 2005 to authorize the NC Agricultural Development and Farmland Preservation Trust Fund (NCADFPTF) under N.C. Gen. Stat. Ann. §§ 106-735 through 106-744 (NC General Assembly, 1985). This fund focuses on conservation, growth, and development of farmland and forestland by encouraging the development of farmland protection plans, conservation easements, and agricultural development projects (NCDA&CS, 2017b). The act also authorizes the creation of voluntary and enhanced voluntary agricultural district programs (discussed below).

The NCADFPTF provides grants to county governments and nonprofit groups to create farmland protection plans and develop other types of programs affecting land use for agriculture (such as Voluntary Agricultural Districts), grants to fund conservation easements, and grants for programs that develop economically viable agriculture operations—such as infrastructure development and market promotion (NC General Assembly, 1985; NCDA&CS, 2017b). When receiving trust fund monies, counties that already have a farmland protection plan are given preference with regard to the amount of county funds they are required to match, depending on their development tier. In July 2015, farmland preservation programs were awarded $2.13 million in recurring funds in the state appropriation budget (NC Office of State Budget and Management, 2015).

Both county governments and nonprofits can apply for NCADFPTF funds. For example, the nonprofit Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project received funds in the 2010 – 2011 grant cycle to develop marketing opportunities for farmers. Orange County used NCADFPTF funds to support a shared-use, value-added processing facility. Cabarrus County used funds to build meat slaughter capacity and infrastructure to expand markets for area livestock producers.

|

Additional Resources for Farmland Protection Plans and Funding

|

Present-use Value Program

North Carolina’s present-use value program (N.C. Gen. Stat. §§ 105-277.3 through 105-277.7) serves as one of the most important working-land preservation tools in North Carolina. Recent updates from the 2015 legislative session have changed some of the parameters of the program, which allows reduced county tax assessments for individually owned property used for agriculture, horticulture, or forestry.

To qualify, applicants must meet requirements for ownership, size, income, and sound management. Generally, farmland must have at least one tract of 10 acres in active production; horticultural land must have at least five acres in active production; and both must generate at least $1,000 in income each year and be under a sound management program. Forestland must be at least 20 acres in size and does not need to generate income but must be managed or harvested according to an approved forest management plan (NC Department of Revenue, 2017).

There are, however, many exceptions and custom approaches. So each landowner applying for the program should rely directly on the NC Department of Revenue’s guidance on this topic. (See “Additional Resources for Present-use Value Programs.”) Property accepted into this program is taxed at its “present-use value” for its farm, forestry, or horticultural use rather than the value of its “highest and best use,” which in many areas would be for residential, retail, or other commercial uses.

The value of farmland is usually less than its market value. The difference between the market value and the present-use value is deferred indefinitely until the land no longer qualifies. When the land ceases to meet eligibility requirements, the difference between the market value and the present-use value for the prior three years and the current year must be repaid.

A farmer’s use of present value as a means to reduce tax rates can be compromised if municipalities enact zoning or other ordinances that reduce the farm’s ability to meet the income eligibility requirement. If land use is not in accordance with present-use value requirements, the owner must pay the difference between the market value and the present-use value for the current and prior three years. Therefore, local governments should consider how their zoning ordinances and other land-use regulations affect farming, forestry, and horticultural activities and whether the ability to meet present-use value income, production, or other requirements might be affected by these regulations.

A conservation easement placed on land currently under present-use value that is annexed at a later time by a municipality may be able to continue to qualify for enrollment in a county’s present-use value even if it is not able to fulfill income or production requirements. S. L. 20160-76 (HB 533) exempts landowners from the three-year tax rollback requirement if they sell PUV-eligible property to a land conservation organization or government agency (NC General Assembly, 2015). This is a significant incentive and can be helpful to farmers in their long-term strategies for succession and estate planning.

|

Additional Resources for Present-Use Value Program

|

Voluntary Agricultural Districts

Voluntary Agricultural District (VAD) programs are established at the county or municipal level to protect farmland from nonfarm development and are authorized under the Agricultural Development and Farmland Preservation Enabling Act (N.C. Gen. Stat. §§ 106-735 through 106-749). As of 2016, agricultural districts (VADs and Enhanced VADs, discussed below) were present in all but 13 of North Carolina’s 100 counties (NCDA&CS, 2015a). Although these programs have been implemented primarily by county governments, municipalities also have the authority under the act to implement their own programs as well. The increased pressure of housing developments in rural areas often prompts the creation of these district programs.

One of the major goals of a VAD program is to increase public awareness of what it means to live near a farm and to prevent nuisance complaints arising from the proximity of nonfarm uses to farming activities and their associated noises, smells, and other agriculture-related characteristics (Figure 8). Farmers identify their membership in the program through mapping of enrolled farms in Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and by using signage that indicates to potential neighbors that the land is used as a farm and participates in a VAD program. This mapping can inform those within some distance of a VAD farm, typically ½-mile, of the potential for noise, odor, dusts, and slow-moving farm vehicles. See Appendix A for an example map of a VAD and the properties that are included within the ½-mile distance for notification purposes. Local governments benefit from VAD programs as the programs provide a mechanism for planning for agricultural development while managing and reducing conflicts between farm and nonfarm land uses.

VADs are created by ordinance at the municipal or county level, and these ordinances may be enacted differently from one jurisdiction to the next. In some programs, land must be enrolled, or qualify to be enrolled, in a county’s present-use value program for it to be enrolled in a VAD program. Other programs across North Carolina may have differing enrollment requirements. For example, programs following the requirements of the Agricultural Development and Farmland Preservation Enabling Act (N.C. Gen.S tat. §§ 106‑735 et seq.) will require that the land be real property that is engaged in agriculture as that word is defined in N.C. Gen. Stat. § 106-581.1.

Landowners must sign a revocable conservation agreement that limits the nonfarm uses and development on the property for 10 years, with the exception of the creation of not more than three lots that meet applicable county zoning and subdivision regulations. By written notice to the county, the landowner may revoke this conservation agreement—with the revocation resulting in the loss of qualifying farm status. Restrictions on nonfarm development and uses are outlined in the Agricultural Development and Farmland Preservation Enabling Act and the Conservation and Historic Preservation Agreements Act (N.C. Gen. Stat. §§ 121-34 through 121-42.). Additionally, highly erodible land must be managed in accordance with Soil Conservation Service defined erosion-control practices.

Landowners can benefit in several ways in exchange for voluntarily restricting nonfarm development and uses on their property for 10 years. The incentives to join are determined locally and vary according to each local government’s ordinance. Many ordinances provide for signage, mapping of enrolled farms in the GIS for the purpose of notifying new neighbors, waiver of water and sewer assessments for enrolled land, and public hearings in the event that enrolled land becomes subject to condemnation by state or local units of government.

Farmers, county commissioners, city councils, and land-use planners can form partnerships to create a VAD program, and these programs should be included in county and municipal farmland protection planning. The Agricultural Advisory Board created as part of the establishment of a VAD also acts as an advisor to the governing board of the county or city on projects, programs, and issues affecting the agricultural economy, including promotion of a sustainable and local food system. For example, Johnston County’s VAD Advisory Board drafted an Agriculture Development Plan that identified growth in local food consumption and production for institutional sales as opportunities for county economic development and recommended improvements in access to local and regional markets at the wholesale and retail levels (Agricultural & Community Development Services LLC, 2010).

|

Additional Resources for Voluntary Agricultural Districts

|

Enhanced Voluntary Agricultural Districts

Both counties and municipalities may establish EVAD programs as authorized by the Agricultural Development and Farmland Preservation Enabling Act. Unlike agreements in the VAD program, EVAD conservation agreements are irrevocable for a period of 10 years and are automatically renewable for a three-year term unless notice of termination is given in a timely manner by either party as provided for in a county or municipality’s EVAD ordinance. Like the VAD program, participation in the EVAD program the land must involve real property that is engaged in agriculture as that word is defined in N.C. Gen. Stat. § 106-581.1 and be enrolled (or qualify to be enrolled) in a county present-use value program (if the ordinance has the latter requirement).

The same benefits allowed under state law for enrollment in a VAD program are also provided to farm operations on land enrolled in an EVAD program. However, participants in an EVAD conservation agreement may obtain additional benefits not provided to VAD participants. These individuals may receive a higher percentage of cost‑share funds for the benefit of the enrolled land under the Agriculture Cost Share Program. Another economic benefit is that farmers who participate can receive up to 25 percent of gross sales from the sale of nonfarm products on the enrolled land and still have those sales qualify as a bona fide farm purpose that may be exempt from county zoning regulations. Finally, state departments, institutions, or agencies that award grants to farmers are encouraged to give priority consideration to individuals farming land subject to an EVAD agreement.

Like the VAD program, municipalities can create and administer their own VAD or EVAD programs or work with a county through an interlocal agreement to participate in a county program. Alternatively, municipalities can have the county administer a municipal VAD or EVAD program. One of the key requirements for participation in some VAD and EVAD programs is enrollment (or qualification for enrollment) in a county’s present-use value program.

Local governments should consider whether their local regulations currently allow land to be used in a way that permits the land to qualify for enrollment in a present-use value program. Without enrollment in present-use value, landowners will not be able to participate in a VAD or EVAD program if this is a program requirement. Additionally, landowners will likely face higher property taxes, which may be one factor that forces farmers to sell their land for development.

|

Additional Resources for Enhanced Voluntary Agricultural Districts

|

Memorandums of Understanding

In North Carolina, counties and municipalities can work together to administer farmland preservation programs through a Memorandum of Understanding, or MOU. Under the Agricultural Development and Farmland Preservation Enabling Act, land cannot be included within a county VAD or EVAD program if it is contained within a municipal corporate boundary. Under this condition, cooperation is necessary between a county and a municipality for a farm to be able to participate in a county program, assuming that the municipality does not have its own VAD or EVAD program.

Working together, both a county and a municipality can economically benefit by preserving working farmlands and by supporting growers and activities on those lands. Landowners benefit through continued participation in a VAD or EVAD program even when their land becomes part of a municipality’s corporate boundaries. To preemptively address nuisance complaints, municipalities can also use VAD and EVAD programs to notify new or prospective residents, property buyers, and developers about farming, forestry, and horticultural activities and the associated noise, smells, or other characteristics of those activities.Often, the cooperation needed entails signing a formal MOU between the county and city governments so that farmland, forestland, and horticultural land contained within a municipality’s corporate boundaries can be enrolled in a county VAD or EVAD program. Additionally, under this type of agreement, when other land is later annexed into a municipality, the land can continue to participate under the county’s VAD or EVAD program.

|

Additional Resources for City and County Memorandums of Understanding for VADs and EVADs

|

Conservation Easements

County governments, municipalities, and nonprofit agencies can work together to obtain conservation easements—restrictions on rights to use or develop land that protect natural resources such as farmland, water, or wildlife. Easements can affect a number of land-use rights and may affect other rights such as water and mineral rights. But easements can be structured to still allow farming, timbering, hunting, and other income-producing activities. The land remains in private ownership, and the easement can be tailored to meet the landowner’s needs. The land encumbered by a conservation easement must be monitored by the easement holder, either a government agency or nonprofit such as a land trust, to ensure the terms of the easement are met. Land trusts are typically the holders of easements.

Conservation easements are usually perpetual, although some may be term easements covering a specific number of years. Term easements, however, do not qualify for state or federal tax benefits. A landowner who donates a perpetual conservation easement may qualify for federal income tax deductions, and his or her heirs may benefit from reduced estate taxes on the land encumbered by the easement.

States may also offer conservation tax credits, although North Carolina’s was repealed in the General Assembly in 2013. Additionally, local property taxes may be reduced if the highest and best-use value of the land is based on development and this use is limited by an easement. Under NC law (N.C. Gen. Stat. § 121‑40), land and improvements subject to an easement are assessed on the basis of their true value less any reduction in their value caused by an easement.

Please note that the NC Conservation Tax Credit program mentioned in previous versions of this guide was eliminated effective December 12, 2013; it was repealed by Session Law 2013-316. If new legislative actions are proposed to reinstate this credit, they would be taken up by the General Assembly in future sessions.

|

Additional Resources for Conservation Easements

|

Land Use and Zoning Ordinances

Ordinances—city and county laws—can affect the location of agricultural activities directly or indirectly by restricting the activities that can take place on designated lands. Counties and municipalities have multiple methods for regulating land use that can provide flexibility for agricultural activities. This section addresses zoning and land use regulation strategies that can be examined for ways to further agricultural development.

Municipalities and Agriculture

Land-use and land-development ordinances together make up one means by which a local government carries out the policies set forth in comprehensive and community development plans. Whether for small-scale farms, larger farming operations, or community backyard gardens, ordinances must be amended to allow for these uses if municipal ordinances do not do so already.

A town may apply various development-related ordinances and programs both inside its town limits and in an area outside the town’s primary corporate limit, referred to as its extraterritorial planning jurisdiction (ETJ). Such an area typically extends not more than one mile outside town limits, but in some cases it may extend up to three miles beyond a municipal boundary. Towns may also obtain authorization from the General Assembly to extend their ETJ even further than that allowed by statute.

A town may enforce its land subdivision ordinance, its zoning ordinance, its soil erosion and sedimentation control ordinance, its flood hazard protection ordinance, and the state building code in its ETJ. For example, if property is added to a city’s ETJ, the land may become subject to municipal land-use ordinances that set standards for the location of farming activities, for buffers between farm and nonfarm uses, and for the height and material of farm fences. However, if a parcel or portion of a parcel is being used for a bona fide farm purpose, as defined and described in N.C. Gen. Stat. § 153A-340(b)(2), it may be exempt from exercise of the municipality's ETJ and the enforcement of these ordinances on that property (see section below on “Bona Fide Farm Exemptions”).

Municipalities still have the responsibility for regulating the construction of barns and other accessory agriculture structures in their ETJs and corporate boundaries. Municipalities are required under state law to enforce the State Building Code, but these structures may be exempt from county enforcement outside of an ETJ. Municipalities, however, can seek local legislation to allow a municipality to include in its zoning ordinance a provision allowing an accessory building used for a bona fide farm purpose in an ETJ to have the same exemption from the building code as it would have under county zoning. In 2011, for example, Session Law 2011-34 was enacted, giving all municipalities in Wake County the authority to provide in their zoning ordinances that an accessory building of a bona fide farm as defined in N.C. Gen. Stat. § 153A-340(b) has the same exemption from the building code as it would have under county zoning.

Under NC law, municipalities may be limited in annexing land if that property is being used for a bona fide farm purpose. The statutory restrictions provided for in Session Law 2011-363 on municipal annexation and the exercise of extraterritorial jurisdiction do not apply to properties already within a town’s corporate boundaries. Thus, properties in a town’s corporate boundaries on which farming, forestry, or horticultural uses are occurring would be subject to regulation of those uses by that town.

Some municipalities in North Carolina have chosen to exempt bona fide farm or agricultural purposes that occur in their corporate boundaries from their zoning and unified development ordinances (UDO), and a 2013 legislative update eliminates the ability of municipalities to annex a property certified as a bona fide farm without owner permission (see section below on “Bona Fide Farm Exemptions”).

Additionally, municipalities are authorized under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 160A‑383.2 to amend ordinances applicable in their planning jurisdiction (corporate boundaries and ETJ) to provide flexibility for farming operations that are located within a city or county VAD or EVAD. This section states that “amendments to applicable ordinances may include provisions regarding on-farm sales, pick-your-own operations, road signs, agritourism, and other activities incident to farming.” Farming for the purposes of this section is defined in N.C. Gen. Stat. § 106‑581.1.

Municipal and County Zoning Ordinances

Zoning, one of the most commonly used land-use planning tools, divides a community into districts and determines the uses and structures allowed in those districts. Under NC law, bona fide farm purposes are exempt from county (and some municipal) zoning ordinances. Municipalities can utilize zoning ordinances to regulate farm operations within their city limits and their ETJs. Sometimes cities integrate their zoning, subdivision, flood hazard protection, and other regulations into a single unified development ordinance (UDO).

Local governments utilizing a UDO can integrate protections and flexibility for agricultural or food-related purposes in multiple ways.

Municipalities can consider agricultural operations by either a district or use category when designing zoning ordinances (Mukherji and Morales, 2010). “Agriculture districts” (such as Residential Agricultural-40) in zoning ordinances are different from VADs, which are not authorized under a local government’s planning and zoning authority. Agriculture districts are common in rural areas and along the edges of urban areas and allow for a wide range of agricultural activities, from raising crops and animals to food processing, distribution, and sales. For example, Orange County created a conditional zoning district for “Agricultural Support Enterprises,” which provides some exemptions for agriculture-affiliated enterprises not covered by the traditional bona fide farm exemption at the state level (Orange County, 2015). (Note that Orange County is one of three counties with a county-funded agricultural economic developer on staff. Mike Ortosky is profiled in a case study associated with this report and his work, along with other ag economic development officers, is explained in more detail in the “Economic and Community Development” section of this guide.)

Zoning for agricultural operations may also be characterized by use category. For example, zoning ordinances can address land use in terms of what types of activities are permitted “as of right” (a use category). Other uses may be deemed special or conditional uses and may be approved by a local government board if it concludes that the use will not detrimentally impact neighboring properties. For example, the Town of Matthews adopted urban farm definitions in its UDO that allow urban farms “as a use under prescribed conditions” in all zoning districts except I-2 Heavy Industrial and AU Adult Uses. Farms must meet the town’s definitions and requirements for accessory uses, structures, and other standards (Town of Matthews, 2014).

Zoning ordinances typically include many requirements that affect agricultural operations. For example, requirements such as lot size, setbacks, parking, sidewalk access, lighting, and traffic could have a major impact on where within the city limits a community garden or other agricultural activity can be located. Ordinances also contain provisions regulating signs and setbacks that may affect agricultural operations. Sign provisions determine how, where, and when a farmer may advertise a particular product or the types of signs that may be used to promote the farm’s name. Setback provisions determine what portions of land must be set aside to meet buffering requirements and may reduce the amount of land available for pasturing livestock or growing crops.

Town councils need to look carefully at these types of land-use issues and consider how to provide for flexibility within their ordinances so that municipalities can allow and support urban agricultural elements such as community gardens, backyard chickens, or local roadside farm stands. Municipalities can add farming, forestry, and horticulture as allowable land uses within zoning ordinances and plans.

For planning tools to be effective, however, all agricultural related terms, land uses, and specification of what uses are exempt need to be carefully defined in land-use plans and ordinances. Clear specifications in the original ordinance prevent confusion that may arise when it comes time to interpret whether or not a use is allowed under the ordinance. Counties should review their zoning ordinances and UDOs to ensure that their definitions and exemptions of bona fide farm purposes comply with statutory exemptions under county zoning while also allowing for activities supported and specified in their farmland protection and land-use plans.

County and municipal government agencies can review their current zoning ordinances for specific language that promotes local food systems. Some issues that may arise include whether zoned agricultural and rural residential districts permit farm and farm-related activities, and whether proposed farmers market sites are within neighborhood business districts. Local governments can also use zoning regulations to improve community access to fresh local foods for sale. For example, mixed-use zones can be designated to permit grocery stores to operate within residential neighborhoods, potentially giving residents easy access to a wider variety of fresh and healthy food.

|

Additional Resources for Land-Use and Zoning Ordinances

|

Bona Fide Farm Exemptions

North Carolina allows local governments to exempt bona fide farms from zoning ordinances through definitions and standards in N.C. Gen. Stat. 153A-340. Bona fide farm purposes are defined here as the production and activities relating to or incidental to the production of crops, grains, fruits, vegetables, ornamental and flowering plants, dairy, livestock, poultry, and all other forms of agriculture.

Evidence of bona fide farm status can be presented in one or more of four ways: a farm sales tax exemption certificate issued by the NC Department of Revenue, a copy of the property tax listing demonstrating eligibility for the Present-Use Value Program (discussed earlier in this section), a copy of Schedule F from the most recent year’s federal tax return, or a forest management plan. These status categories exclude farms subject to a conservation agreement. Information for excluded farms is available in N.C. Gen. Stat. § 106-743.2-4 (NC General Assembly, 2011).

In September 2013, this legislation was updated to expand the exemption from county zoning, eliminate the ability of municipalities to enforce zoning on bona fide farms in their extraterritorial jurisdictions, and prevent municipalities from annexing such farms without owner consent. The exempt activities expansion included provisions for activity associated with a farm and “any other farm owned or leased … by the bona fide farm operator, no matter where located.” This allows energy production and processing facilities that serve multiple farm tracts to be considered as exempt from zoning.

The update also included rules to exempt grain warehouses and storage facilities from zoning by counties and municipalities in ETJ districts, and directed the NC Department of Transportation to adopt rules for vegetation pruning that emphasized agritourism activity viewing along federal and state highways.

|

Additional Resources for Bona Fide Farm Exemptions

|

General Ordinances

Local governments also need to examine the impacts on agriculture from general ordinances, such as animal control, nuisance, and landscaping ordinances. These ordinances contain provisions separate from those enacted under a local government’s planning and zoning authority and will not be contained within either a zoning or UDO, but instead are listed in separate sections of the local government’s code of ordinances.

All local ordinances should be enacted and enforced together in a consistent manner to allow for desired rural or urban agricultural activities. Where a zoning ordinance allows for livestock in one or more districts, the animal control ordinance for a county or municipality needs to be written so that the care and keeping of livestock is allowed within a local government’s boundaries and planning jurisdiction.

Additionally, nuisance and noxious weed ordinances that regulate vegetation height should be written to allow for crops in gardens or on farms, which will grow beyond vegetation height restrictions that are enacted to control overgrown, weedy vegetation on unmaintained lots. Some gardeners within city limits may run the risk of potential fines and neighborhood discord if their gardens do not meet vegetation height restrictions.

|

Additional Resources for General Ordinances The following websites provide general information about local governments and ordinances:

|

Trends and Emerging Issues in Local Food System Development

Unique approaches to planning for agricultural development and food entrepreneurship occur all across North Carolina. Here we discuss some emerging trends and strategies from the national level that are being explored in North Carolina. (For information about mobile markets and farmers markets, see the expanded section in the “Economic and Community Development” section of this guide.)

Additionally, the NC Growing Together Project has prepared case studies from every region of North Carolina that showcase some of these trends.

Conservation Development and Agrihoods

Conservation development strategies have been increasingly popular over the last four decades. This development approach focuses on the protection of natural resources while also creating economic benefits and includes a wide range of projects—from rural ranches, to suburban conservation subdivisions, to large master-planned communities. As of 2016, conservation development accounted for nearly a quarter of private land conservation in the United States (Colorado State University, 2016).

Land conservation is a continuously challenging field, working within larger trends of land development, climate issues, and financing methods. Conservation development incorporates the need for residential housing and development with an emphasis on stewardship in the design, construction, and maintenance of residential facilities. Some conservation development projects protect a percentage of the property through conservation easements obtained by the developer-owner of the property. Other projects offer a way for farmers to protect a majority of their farmland while allowing development in a concentrated area, like this example from the Hudson Valley, where both farmland and housing are at a premium.

Another increasingly popular strategy for conservation development is the design and construction of “agrihoods,” developments centered around a common resource. Instead of golf courses or swimming pools, residents build on sites located around agricultural uses like farms and gardens. This strategy addresses a common desire for potential buyers to have views and open space without the large capital investments needed in golf courses or other amenities, and assists developers both in selling lots and in obtaining tax credits and protections based on their use of conservation easements.

Some developments hire professionals to manage the farming activities and deliver produce boxes to residents each week, while others offer allotments of farm or garden space to owners (Locke, 2016). One example that was recently approved in Durham County is Wetrock Farm. The project would place roughly half the 287-acre development property into conservation as a working farm, while including fresh produce as a benefit of the homeowners’ association dues (Bracken, 2016). Fundraising continues at the time of this publication.

Counties and municipalities have the regulatory authority to utilize specific guidelines and incentives to encourage conservation development in local land use regulations in many ways, such as density bonuses, conservation easement assistance in partnership with local land trusts, and assistance with ecological site mapping and protection plans (Reed, Hilty, and Theobald, 2014). However, the use of zoning as an incentive exclusively for farms is rare in the state, although flexible development options have been adopted by some counties by which developers can decrease lot sizes and get “bonus units” for additional preserved acreage. The option is rarely used due to a lack of incentives for developers to take advantage of those programs (Belk, 2014). For examples, see City of Durham’s Article 6: District Intensity Standards (City of Durham, 2016); Franklin County’s Flexible Development standards (Franklin County, 2017); and Orange County’s Article 7: Subdivisions—Cluster Development—Payments in Lieu of Dedication standards (Orange County, 2011).

|

Additional Resources for Conservation Development and Agrihoods

|

Food Trucks

One of the most common requests among planners is information about how to properly zone areas for food trucks and other niche food businesses, including mobile markets, CSA distribution sites, cooking or gardening classes, and other activities not easily defined in existing use categories (Figure 9).

Many North Carolina counties and municipalities have addressed these issues through zoning or policy changes, particularly to allow mobile markets and food trucks to locate in commercial or industrial areas and to allow permits for multiple units in a given location (such as food truck “rodeos” or “rallies,” or defined “food truck lots” that target employees of a specific industry or commercial district).

For more information, see the APA’s guidance on food trucks.

Beehives

Another common issue is the maintenance and use of beehives in urban districts. The 2016 Local Government Regulatory Reform Bill (N.C. Gen. Stat. § 106-645) states that county ordinances cannot prohibit possession of five or fewer hives, although some municipal regulation of hives may be allowed (but up to five hives within the planning jurisdiction must be allowed). Ordinances may regulate setbacks, anchors, or location, but may not prohibit hives from being installed altogether (NC General Assembly, 2015).

Public Land for Community Gardens and Incubator Kitchens

Many states, counties, and towns are providing public land for food projects like community gardens and incubator commercial kitchens. Often, land and facilities are already in public use, and these uses are added to existing space or facilities, such as those at recreation centers, libraries, hospitals or health clinics, education boards, schools, government housing projects, and other locations (Winig and Wooten, 2015). In the City of Greensboro, a food access report led the city to explore using its network of recreation centers throughout the city to host incubator kitchens on-site, providing quick and easy access to food and food entrepreneurship activities in existing facilities (City of Greensboro, 2015).

For more resources on using public land, see the “Vacant Land for Food System Development” subsection in the “Economic and Community Development” section of this guide.

Military Food Systems Planning Initiatives

Military bases in all branches of the U.S. Department of Defense have begun to consider land protection and conservation efforts in base regions over the past 10 years. Base leaders are often concerned about encroachment near the bases, which can inhibit training programs, affect housing needs for base families, and impact transportation, infrastructure, and land use in the area.

Many bases have begun to work with local and regional planners to identify strategies for protecting land around bases and beneath flight or training areas. This can often mean military support for state and local programs that protect farmland in permanent or semipermanent conservation easements. As part of the Department of Defense’s Sentinel Landscapes initiative, bases in North Carolina have begun addressing these issues: Camp Lejeune (U.S. Marine Corps), Jacksonville; Ft. Bragg (U.S. Army), Fayetteville; and some regional U.S. Air Force facilities. Camp Lejeune has also supported farmers markets on the base for active personnel and other community initiatives such as an incubator farm to encourage more market channel availability for farmers in their encroachment region (Edmonds, 2015) (Figure 10).

Planning for food systems in conjunction with military entities aligns two of a state’s larger industries—military and agricultural—and emphasizes their common goals of land protection and conservation. A number of market-based opportunities for land preservation and farm market channel expansion are available as tools to encourage food system expansion in military zones.

|

Additional Resources for Military Food Systems Planning Initiatives

|

Economic and Community Development for Local Food Economies

Incorporating Local Food Systems into Economic and Community Development Strategies

Local economies can accrue several benefits from the presence of small agriculture enterprises and food entrepreneurship in their communities. Local governments, regional councils, and planners and economic developers have a unique opportunity to support recruitment and expansion efforts in this sector, thereby increasing job opportunities, keeping more money circulating within local communities, and enhancing the ability of residents to remain in rural areas.

Recent work in the area of local food system development measures the benefits of this work using a return on investment (ROI) perspective, which includes not only economic benefits but also social and environmental benefits connected to quality of life. This work takes place at the intersection of planning and economic development approaches to building stronger communities. The City of Raleigh planning and economic development staff, for example, jointly use an ROI-based development strategy that takes into account the economic impacts of planning and development decisions (Nettler, 2013). Minnesota GreenStep Cities (2015) provides an ROI guide that accounts for urban investments in green space, gardens, and urban farms.

For the local food system to flourish, much of the food-processing infrastructure for small and medium-sized farms may need to be developed. Farmers need centers to aggregate produce, commercial kitchens to create value-added products (such as jams or sauces), slaughter facilities, and value-added meat-processing facilities. Producers also need access to a variety of markets and viable farmland, and a food system that connects them into the existing networks for transportation, distribution, storage, and other critical needs.

When planning new initiatives to promote economic development, local governments should consider their agricultural assets and what kinds of consumer demand and available supply are present within a region. There are several ways for counties and towns to support the development of local food systems, many of which are outlined below. This section of the guide also includes information on using local foods to attract, retain, and expand businesses of all sizes and industries.

Innovation in Planning and Economic Development

Integrating food systems and planning can provide innovative opportunities at the leading edge of the planning sector, especially in regionalism, multidisciplinary planning, and applied technology. Regionalism, an economic development and planning approach that considers needs across a defined geographic area, includes multiple units of local government and allows for long-term market-based partnerships as well as coordinated strategies for development (Association of Wisconsin Regional Planning Commissions, 2014).

By its nature, agriculture is a regional enterprise and offers communities a way to work together on important development issues. Food systems also bring together a diverse group of stakeholders from multiple industries and motivations (see “Collaborating for Growth” in this guide). This allows planners to use multiple approaches, particularly from economic development, health, and design partners, to solve complex problems that affect every population within a community. Food systems planning and development is at the leading edge of innovation in public service, offering multiple ways for unique solutions to be implemented.

Calculating Economic Impact

|

SO, WHAT'S LOCAL? There is no fixed definition of "local.” |