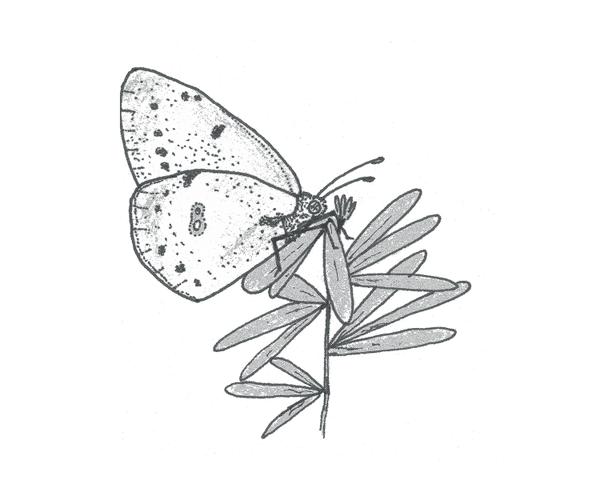

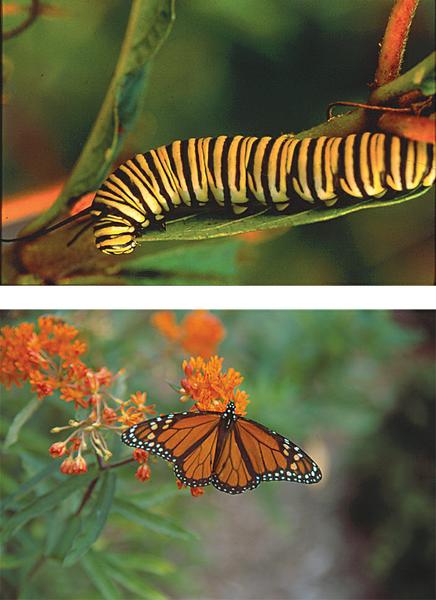

Butterfly watching, though unlikely to match the widespread popularity of bird watching, has gained significant favor in recent years. Butterflies are colorful, diverse, abundant, and active during the day in warm months, making them an ideal pursuit for wildlife watchers (Figure 1). In fact, wildlife watching as a whole, given impetus by the increased awareness of regional and ecological diversity, has become one of this country’s fastest-growing outdoor recreational activities.

Butterflies and caterpillars (the larval stage in the butterfly life cycle) provide food for birds and other organisms, pollinate flowers, and are easy to attract to a garden or backyard landscape. Butterflies are found throughout North Carolina and will flourish within a well-designed landscape of native plants in both rural and urban areas. Planting a variety of both nectar plants for adults and host plants for caterpillars in a sunny location will ensure many hours of viewing pleasure as butterflies visit your garden.

Common Butterflies of North Carolina

North Carolina’s diverse landscape includes coastal dunes, pocosins, sandhill savannahs, piedmont forests, wetlands, and mountain ranges. These different vegetation communities provide a home for more than 175 butterfly species. Some species are found statewide, while others are restricted to a specific vegetation type or region. Scientists classify species into a series of genera and families, based upon similar genetics or similar physical characteristics. Here is a sampling of the butterflies you are likely to encounter in North Carolina:

Family Papilionidae (swallowtails)

Pipevine Swallowtail (Battus philenor)

Zebra Swallowtail (Eurytides marcellus)

Black Swallowtail (Papilio polyxenes)

Eastern Tiger Swallowtail (Papilio glaucus)

Spicebush Swallowtail (Papilio troilus)

Palamedes Swallowtail (Papilio palamedes)

Family Pieridae (sulphurs, whites, and yellows)

Cabbage White (Pieris rapae)

Clouded Sulphur (Colias philodice)

Orange Sulphur (Colias eurytheme)

Cloudless Sulphur (Phoebis sennae)

Sleepy Orange (Eurema nicippe)

Family Lycaenidae (gossamer-wings)

Gray Hairstreak (Strymon melinus)

Red-Banded Hairstreak (Calycopis cecrops)

Eastern Tailed-Blue (Cupido comyntas)

Summer Azure (Celastrina neglecta)

Family Nymphalidae (brushfoot butterflies)

American Snout (Libytheana carinenta)

Variegated Fritillary (Euptoieta claudia)

Great Spangled Fritillary (Speyeria cybele)

Pearl Crescent (Phyciodes tharos)

Question Mark (Polygonia interrogationis)

Eastern Comma (Polygonia comma)

Mourning Cloak (Nymphalis antiopa)

American Lady (Vanessa virginiensis)

Red Admiral (Vanessa atalanta)

Common Buckeye (Junonia coenia)

Red-Spotted Purple (Limenitis arthemis astyanax)

Viceroy (Limenitis archippus)

Monarch (Danaus plexippus)

Family Hesperiidae (skippers)

Silver-Spotted Skipper (Epargyreus clarus)

Long-Tailed Skipper (Urbanus proteus)

Southern Cloudywing (Thorybes bathyllus)

Juvenal’s Duskywing (Erynnis juvenalis)

Horace’s Duskywing (Erynnis horatius)

Least Skipper (Ancyloxypha numitor)

Fiery Skipper (Hylephila phyleus)

Sachem (Atalopedes campestris)

Clouded Skipper (Lerema accius)

Life Cycle

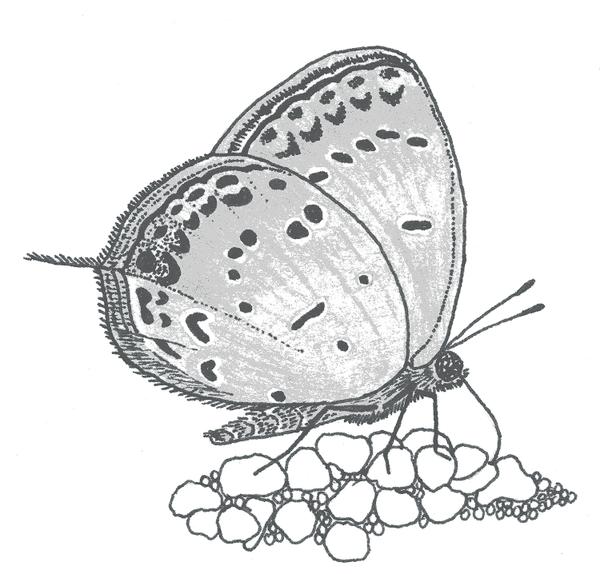

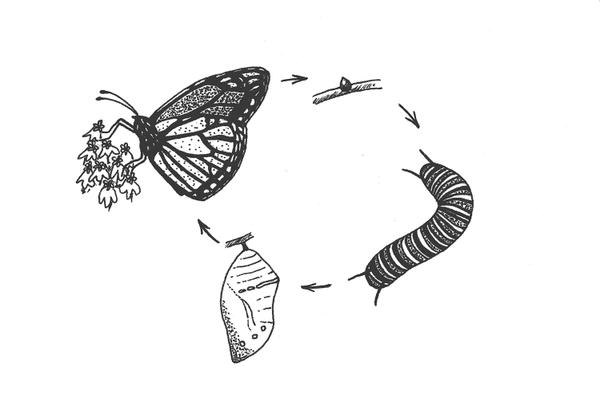

Butterflies and moths are unique because they change from a caterpillar to a winged adult through a process called metamorphosis (Figure 7). A typical butterfly’s life begins as an egg, generally laid on the leaf of a host plant. A host plant is a plant that caterpillars like to eat. Eggs soon hatch into caterpillars, which act as eating machines to devour leaves of the host plant. Caterpillars often have very specific food requirements that restrict them to just one or a few plant species (Figure 8, top). After a few weeks, the caterpillar molts into a mummy-like stage with a hard protective casing, called a pupa or chrysalis. While in the chrysalis, the caterpillar transforms into an adult. At the end of about two weeks, the adult emerges from the chrysalis, spreads and dries its wings, and begins searching for food and a mate (Figure 8, bottom). Following successful mating, the female begins her search for a host plant on which to deposit her eggs, and the life cycle begins again.

Physiology and Behavior

- Butterflies and moths are insects in the order Lepidoptera, meaning “scaly-winged.” A person who studies these creatures is called a “lepidopterist.”

- Moths may have whip-like, fern-like, or fuzzy antennae with no knobs at their ends. Butterfly antennae are smooth, thin, and whip-like with a terminal knob.

- Butterfly wings are covered with thousands of tiny overlapping scales arranged like shingles on a roof. A butterfly can fly even if these scales are removed.

- Colors such as blue, green, violet, gold, and silver on butterfly wings are not caused by pigment, but rather by light reflecting off the wing scales.

- Depending upon the species, adult butterflies can live from one week to nine months.

- Butterflies (and other insects) have an exoskeleton, or structural support on the outside of their bodies, to protect them and keep in fluids so they don’t dry out.

- Butterflies and caterpillars breathe through “spiracles,” which are tiny openings along the sides of their bodies.

- Butterflies can smell with their antennae.

- Butterflies have compound eyes that allow them to see the colors red, green, and yellow. Their eyes do not rotate to follow a predator’s movement; rather, they detect movement as the object moves from one facet of the eye to the next.

- Butterflies use special nerve cells called chemoreceptors on the pads of their feet to “taste” food and identify leaves of their caterpillar’s host plant before they lay their eggs.

- In some butterfly species, females and males look different. Their colors may vary slightly, and females generally are larger than males. But size cannot be used to distinguish between the sexes because individuals of any single species may vary in how big they are, depending on the amount and quality of food they ate as caterpillars.

- Most butterflies lay their eggs on a specific type of plant, called their host plant, which their caterpillars later feed on (Figure 9). Exceptions include Harvester caterpillars, which eat woolly aphids, and a few other caterpillars that eat rotting leaves rather than living plant foliage.

- Adult butterflies may feed on nectar from flowers, but some prefer rotten fruit or tree sap. They suck the liquid food through a straw-like “tongue” called a proboscis, which curls up under the head like a watchspring when not in use.

- Male butterflies often congregate at “puddling” areas, which include mud puddles, moist soil along stream banks, and animal scat (Figure 10). There they ingest salts important in sperm production.

- Different species of butterflies have characteristic behaviors. For example, some perch on leaves, guarding an area and flying out to investigate all intruders. Others appear to constantly patrol certain areas and rarely perch.

- Butterflies bask in the sun to warm their bodies before they fly (Figure 11). Their wings act as solar collectors.

- Butterflies are most active during the warmest parts of the day, but in temperatures of over 100°F, they may become overheated and seek shade.

- Most species of butterflies survive the winter by hibernating as caterpillars, pupae, or adults. A few spend the winter as eggs. Fewer still migrate to warmer climates.

- Those species that spend the winter as adults tuck themselves behind loose bark or in tree cavities. They emerge in search of sap or rotten fruit on warm, sunny days.

- Eggs, caterpillars, and adult butterflies have many predators. To avoid them, females lay eggs in concealed locations on the host plant, and caterpillars often look inconspicuous. To scare away predators, some caterpillars have large eye-spots that resemble a snake’s head. Other caterpillars have protective spines, release obnoxious scents, or just plain taste bad.

Using Native Plants to Attract Butterflies

Native plants generally are defined as those that occurred in North America before European settlement. Non-native, or exotic, plants are those that are not native. Plants native to your area grow well because they are specifically adapted to the climate, soils, temperature, and precipitation. Native plants are those to which regional butterflies have adapted, and therefore, they are ideal for butterfly gardening and for larger restoration projects (Figure 12).

Why focus on native plants for butterfly habitat?

- These plants require relatively little maintenance, watering, or care because they are adapted to a particular area.

- Native plants will attract butterflies native to the region. Caterpillars are very picky eaters and will eat only very specific host plants; native plants provide these specific food sources.

- Some non-native plants grow with excessive vigor and compete for space with native plants. Because some non-natives could “escape” from your garden and threaten nearby wild habitat, they should be specifically avoided (see Landscaping for Wildlife with Native Plants, AG-636-03)

- Most ornamental plants are bred for color and bloom size, not for nectar production. While these cultivars may be attractive to us, many provide little benefit to wildlife.

Creating a Butterfly Habitat

Diversity

An effective butterfly habitat provides everything a butterfly needs to complete its life cycle.

- Provide a good diversity of host plants to attract a variety of butterflies and their caterpillars (see Table 1). Caterpillars are voracious but picky eaters, and many feed only on a particular species of plant.

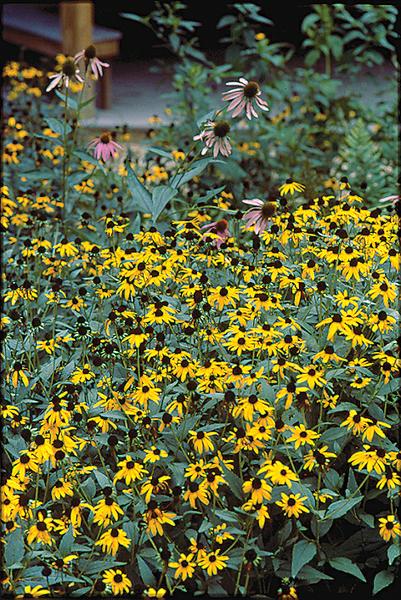

- Choose a variety of nectar plants that will provide food throughout the growing seasons, as different species of butterfly are active from early spring through late fall (see Table 2) (Figure 13).

- Choose flowers with blooms of different sizes and depths (Figure 14). Smaller butterflies, such as hairstreaks and skippers, have shorter proboscises and are unable to reach the nectar in larger blooms. Larger butterflies, such as swallowtails, favor larger blooms.

- Consider the moisture and light requirements of plants before introducing them to your butterfly habitat. Choose only the plants most appropriate for your area.

- Visit butterfly gardens at local nature centers or botanical gardens and observe which flowering plants attract butterflies.

- Do not get discouraged if a particular plant does not attract butterflies as anticipated. Experiment and find out which plants work in your butterfly habitat (Figure 15).

- Peelings and cores of fruit (peeled, overly ripe bananas work well) can be discarded in partially shaded nooks in the garden where they will attract butterflies that eat rotting fruit.

Design

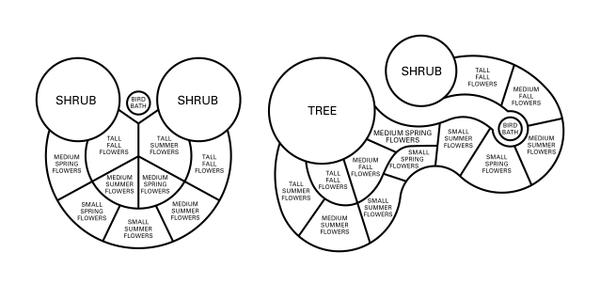

Plan your butterfly habitat before buying and putting in any plants (Figure 16). Decide how much space you want to dedicate to your butterfly habitat.

- Map the area in its current condition, then create a map for your projected habitat, making sure to provide for all the basic butterfly needs (sun, shelter, larval host plants, and adult nectar plants).

- Your butterfly habitat will function best in a sunny location. Most butterflies are active only in the sun, and many butterfly larval and nectar plants require sunny spots.

- Place taller plants and shrubs behind smaller plants and ground covers to maximize visibility and enjoyment of your design (Figure 17).

- Concentrate flowering plants with similar blooming periods to allow butterflies easy access to seasonally abundant nectar sources without excessive movement and increased exposure to predators (see Table 2) (Figure 18).

- Many nectar and larval host plants grow tall. Taller plants and shrubs provide butterflies with shelter from wind and rain.

- Remember that many of your plants will grow larger and multiply each year as they mature. Be sure to leave room for each plant to grow and expand.

- Do not dig plants from the wild unless you are part of an organized plant rescue. Select nursery-grown native species or cultivate your own from nursery-bred native seeds. By using nursery stock from a reputable dealer, you will help preserve your local environment and the native plant population.

- Make “puddling” (ingestion of salts from watery or damp ground) easy for male butterflies by designing water puddles and wet, sandy areas into the habitat and by allowing animal feces to remain in the landscape.

- Provide a few large flat rocks for butterflies to perch on while basking in the sun.

- You can provide shelter for the butterflies in your habitat by leaving snags (standing dead trees) or a brush pile. There is little evidence to suggest that butterflies actually use butterfly houses.

Maintenance

- Throughout the growing season, leave the dead flower heads and dead foliage on your plants or you may accidentally remove eggs or pupating butterflies.

- If neatness is in your blood, consider allocating a few plants as butterfly host plants. Leave those plants alone, but remove and relocate caterpillars from individual plants, if you like.

- Wildlife habitat, whether for birds or butterflies, is best left untidy. As native grasses and wildflowers grow, bloom, and set seed, they may grow fast, tall, and a bit scraggly. Nature is not always perfectly ordered, and the most effective butterfly gardens will follow in nature’s footsteps.

- To keep your garden looking and performing its best requires research, planning, and annual maintenance. Although you’ll probably discover that many butterflies quickly find your new plantings, expect to wait several years before your butterfly garden becomes fully established and, therefore, fully appreciated by the butterflies.

<

| Plant Type | Scientific Name | Common Name | Butterfly Larvae |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trees | Betula alleghaniensis | Yellow Birch | Mourning Cloak, Dreamy Duskywing |

| Betula lenta | Sweet Birch | ||

| Betula nigra | River Birch | ||

| Carya glabra | Pignut Hickory | Banded Hairstreak | |

| Carya tomentosa | Mockemut Hickory | ||

| Celtis laevigata* | Hackberry | American Snout, Mourning Cloak, Question Mark, Hackberry Emperor, Tawny Emperor | |

| Celtis tenuifolia | Sugarberry | ||

| Chamaecyparis thyoides | Atlantic White Cedar | Hessel’s Hairstreak | |

| Fraxinus americana | White Ash | Eastern Tiger Swallowtail | |

| Ilex opaca | American Holly | Henry's Elfin | |

| Juniperus virginiana | Eastern Redcedar | Juniper Hairstreak | |

| Liriodendron tulipifera* | Yellow Poplar | Eastern Tiger Swallowtail | |

| Persea borbonia | Redbay | Palamedes Swallowtail | |

| Pinus echinata | Shortleaf Pine | Eastern Pine Elfin | |

| Pinus taeda | Loblolly Pine | ||

| Populus deltoides | Cottonwood | Viceroy, Red-Spotted Purple | |

| Prunus americana | Wild Plum | Coral Hairstreak, Eastern Tiger Swallowtail, Red-spotted Purple, Spring Azure, Viceroy | |

| Prunus angustifolia | Chickasaw Plum | ||

| Prunus serotina* | Black Cherry | ||

| Quercus spp. | Oaks | Banded Hairstreak, Edward’s Hairstreak, Gray Hairstreak, White-M Hairstreak, Horace’s Duskywing, Juvenal’s Duskywing | |

| Robinia pseudoacacia* | Black Locust | Clouded Sulphur**, Zarucco Duskywing, Silver-Spotted Skipper | |

| Salix caroliniana | Carolina Willow | Eastern Tiger Swallowtail, Mourning Cloak, Eastern Comma**, Red-spotted Purple, Viceroy | |

| Salix nigra* | Black Willow | ||

| Sassafras albidum* | Sassafras | Spicebush Swallowtail | |

| Ulmus alata | Winged Elm | Painted Lady**, Eastern Comma, Mourning Cloak, Question Mark, Red-spotted Purple** | |

| Ulmus americana* | American Elm | ||

| Small Trees | Alnus serrulata | Alder | Harvester (carnivorous larvae eat woolly aphids commonly found on alder) |

| Amelanchier arborea | Serviceberry | Red-spotted Purple, Viceroy** | |

| Asimina triloba | Pawpaw | Zebra Swallowtail | |

| Carpinus caroliniana | Ironwood | Eastern Tiger Swallowtail, Red-spotted Purple | |

| Cercis canadensis | Redbud | Henry’s Elfin | |

| Cornus florida | Flowering Dogwood | Spring Azure | |

| Crataegus spp. | Hawthorn | Gray Hairstreak, Red-spotted Purple**, Viceroy** | |

| Myrica cerifera | Wax Myrtle | Red-banded Hairstreak | |

| Rhus copallinum | Winged Sumac | Red-banded Hairstreak | |

| Rhus glabra | Smooth Sumac | ||

| Symplocos tinctoria | Sweetleaf | King’s Hairstreak | |

| Shrubs | Asimina parviflora | Dwarf Pawpaw | Zebra Swallowtail |

| Ceanothus americanus | New Jersey Tea | Mottled Duskywing | |

| Gaylussacia dumosa | Dwarf Huckleberry | Henry’s Elfin | |

| Gaylussacia frondosa | Blue Huckleberry | ||

| Ilex glabra | Inkberry | Henry’s Elfin | |

| Lindera benzoin | Spicebush | Palamedes Swallowtail, Spicebush Swallowtail | |

| Phoradendron leucarpum | Mistletoe | Great Purple Hairstreak | |

| Vaccinium arboreum | Sparkleberry | Brown Elfin | |

| Vaccinium corymbosum | Highbush Blueberry | ||

| Vaccinium stamineum | Deerberry | ||

| Vines | Aristolochia macrophylla | Dutchman’s Pipe | Pipevine Swallowtail |

| Passiflora incarnata | Passionflower | Gulf Fritillary, Variegated Fritillary, Zebra Heliconian | |

| Herbs and Wildflowers | Agalinus spp. | Gerardia | Common Buckeye |

| Antennaria plantaginifolia | Plantain-Leaved Pussytoes | American Lady | |

| Antennaria solitaria | Solitary Pussytoes | ||

| Aristolochia serpentaria | Virginia Snakeroot | Pipevine Swallowtail | |

| Aruncus dioicus | Goat’s Beard | Dusky Azure | |

| Asclepias incarnata | Swamp Milkweed | Monarch | |

| Asclepias syriaca | Common Milkweed | ||

| Asclepias tuberosa | Butterfly Weed | ||

| Asclepias variegata | White Milkweed | ||

| Aster carolinianus | Climbing Aster | Pearl Crescent | |

| Aster novae-angliae | New England Aster | ||

| Baptisia tinctoria | Wild Indigo | Wild Indigo Duskywing | |

| Boehmeria cylindrica | False Nettle | Eastern Comma, Question Mark, Red Admiral | |

| Chamaecrista fasciculata | Partridge Pea | Cloudless Sulphur, Little Yellow, Sleepy Orange | |

| Chelone glabra | White Turtlehead | Baltimore Checkerspot, Common Buckeye** | |

| Cimicifuga racemosa | Black Cohosh | Appalachian Azure | |

| Cirsium horridulum | Yellow Thistle | Little Metalmark, Painted Lady | |

| Desmodium spp. | Beggarlice | Silver-Spotted Skipper, Hoary Edge, Northern Cloudywing, Southern Cloudywing, Gray Hairstreak, Eastern Tailed-Blue | |

| Eutrochium fistulosum | Joe-Pye-Weed | Pearl Crescent | |

| Gnaphalium obtusifolium | Rabbit Tobacco | American Lady | |

| Helianthus atrorubens | Sunflower | Silvery Checkerspot | |

| Laportea canadensis | Wood Nettle | Eastern Comma, Red Admiral | |

| Lespedeza capitata | Bush Clover | Eastern Tailed-Blue | |

| Lespedeza virginica | Virginia Bush Clover | ||

| Linaria canadensis | Blue Toadflax | Common Buckeye | |

| Penstemon laevigatus | Smooth Beardtongue | Common Buckeye | |

| Ruellia caroliniensis | Wild Petunia | Common Buckeye | |

| Tephrosia virginiana | Goat’s Rue | Southern Cloudywing, Northern Cloudywing | |

| Thaspium barbinode | Meadow Parsnip | Black Swallowtail | |

| Thaspium trifoliatum | Hairy-Jointed Meadow Parsnip | ||

| Trifolium carolinianum | Carolina Clover | Clouded Sulphur, Eastern Tailed-Blue, Orange Sulphur, Gray Hairstreak, Northern Cloudywing | |

| Trifolium reflexum | Buffalo Clover | ||

| Urtica chamaedryoides | Heartleaf Nettle | Painted Lady**, Eastern Comma, Question Mark, Red Admiral | |

| Urtica dioica | Stinging Nettle | ||

| Viola spp. | Violets | Fritillaries | |

| Zizia aptera | Heart-Leaved Alexanders | Black Swallowtail | |

| Zizia trifoliata | Golden Alexanders | ||

| Grasses and Sedges | Andropogon spp. | Bluestem, Broomsedge | Common Wood-Nymph, Various Skippers |

| Erianthus spp. | Plumegrass | ||

| Panicum spp. | Panic Grasses | ||

| Schizachyrium scoparius | Little Bluestem | ||

| Tridens flavus | Purple Top | ||

| Arundinaria gigantea | Switchcane | Southern Pearly-eye, Creole Pearly-eye, Various Skippers | |

| Carex spp. | Sedges | Various Satyrs | |

| Uniola latifolia | River Oats | Northern Pearly-eye |

* Trees that can be pruned and kept at shrub size by cutting them to the ground every 2-3 years. In this way, people with small yards can increase tree species diversity. ↲

** Rarely uses this host plant in North Carolina. ↲

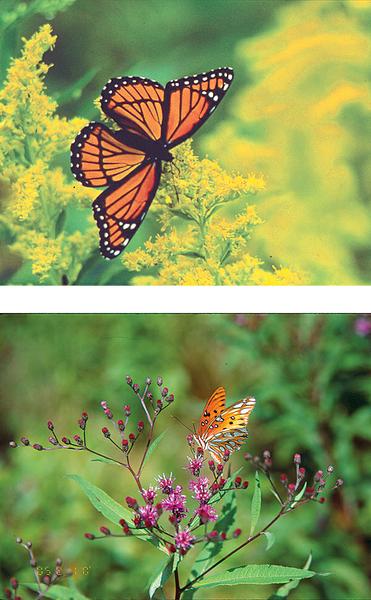

Figure 13. Goldenrod (top), ironweed (bottom), and other late-flowering plants provide important nectar sources for butterflies like the Viceroy (top) and Gulf Fritillary (bottom) during a time of the year when many popular ornamentals are not in bloom.

Top photo courtesy of Thomas G. Barnes, University of Kentucky; bottom photo by Chris Moorman

Butterfly Conservation

- Encourage your neighbors and local school officials, businesses, or parks officials to put in butterfly plantings of their own so you all can create a network of butterfly gardens throughout your community.

- Gardening with native plant species can increase critical habitat for both larvae and adult butterflies.

- Minimize the use of pesticides. Chemicals that kill insect pests also kill butterflies and beneficial insects. Pesticides can be toxic to birds, too, and runoff can contaminate streams and water systems.

- Butterfly releases at weddings or other occasions have become popular, but are not recommended for a number of reasons. These butterflies can spread diseases to the native butterfly population. They may interbreed with the native population, causing genetic problems or interfering with natural migration patterns. They also generally die quickly because they are released during an inappropriate season or are not equipped to handle the particular environment where they are released.

Email Forum

CarolinaLeps is a listserve-style email forum for butterfly enthusiasts to discuss all aspects of butterfly life in the Carolinas, including butterfly finding, butterfly identification, trip reports, butterfly counts, butterfly behavior, backyard butterflying, butterfly gardening, butterfly photography, and butterfly club information. To subscribe, send the message text “subscribe carolinaleps” (without the quotation marks) to sympa@duke.edu. Leave the subject line blank, and do not write anything else in your message text. You will receive an automated confirmation, which includes a file of information. For more details, visit CarolinaLeps.

Additional Resources

Ajilvsgi, G. 1990. Butterfly Gardening for the South. Dallas, Texas: Taylor Publishing Co.

Barnes, T. G. 1999. Gardening for the Birds. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky.

Brock, J. P., and K. Kaufman. 2003. Butterflies of North America. Singapore: Hillstar Editions L.C.

Glassberg, J. 1999. Butterflies Through Binoculars, The East. New York: Oxford University Press.

Glassberg, J. 2012. A Swift Guide to Butterflies of North America. Sunstreak Books.

Opler, P. A., and R. T. Peterson. 1992. Field Guide to Eastern Butterflies (Peterson Field Guides). New York: Houghton Mifflin Co.

Pyle, R. M., and S. A Hughes. 1992. Handbook for Butterfly Watchers. New York: Houghton Mifflin Co.

Wasowski, S., and A. Wasowski. 1994. Gardening with Native Plants of the South. Dallas, Texas: Taylor Publishing Co.

For more information, click the resources below or request the following Working With Wildlife (WWW) and Urban Wildlife (AG) publications from your local Cooperative Extension Center.

- Songbirds, WWW-4

- Snags and Downed Logs, WWW-14

- Hummingbirds and Butterflies, WWW-20

- Managing Backyards and Other Urban Habitats for Birds, AG-636-01

- Landscaping for Wildlife with Native Plants, AG-636-03

Funding for creation of this publication was provided in part through an Urban and Community Forestry Grant from the North Carolina Division of Forest Resources, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, in cooperation with the USDA Forest Service, Southern Region.

Publication date: Feb. 3, 2026

AG-636-02

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.