This fact sheet addresses the question of what local communities and landowners can do today to minimize the impacts of tidal floods. It reviews devices that can be used to modify or “retrofit” ditches and underground pipe systems to improve water management in urban and rural coastal communities over short timescales (several years). Landowners, town engineers, planners, and stormwater managers are the target audience for this fact sheet.

What Is Tidal Flooding?

Stormwater management systems are designed to move stormwater away from roads and buildings, and into the surrounding ditches, waterways, and underground pipe networks. In coastal communities, ditches and underground pipe networks use gravity to move stormwater from high areas to low areas, typically emptying into the ocean, sounds, or tidal creeks. To allow stormwater to drain properly, ditch outlets and the ends of pipes, also known as “outfalls,” must be above water (Figure 1). When ditch outlets or outfalls are submerged by saltwater, stormwater can quickly fill the remainder of the ditch or pipe and then back up onto roads and surrounding areas, causing flooding to occur. This type of flooding is referred to as a compound flood, because it occurs from the combined effects of rain and high water levels in the ocean, sounds, or tidal creeks. Compound floods are more likely to occur when rain falls around high tide, which is when pipe outfalls are more likely to be submerged and ditches are more likely to be filled with saltwater.

Floods in coastal communities can also occur due to high tides alone. These floods are referred to by many names, including nuisance tidal floods, high-tide floods, and king-tide floods. Because these floods can occur on sunny days without rainstorms, they are also sometimes referred to as sunny-day floods or blue-sky floods. During these floods, tidal water may come up through ditches or underground pipe networks to flood yards and roads, or spill over low shorelines.

There are other factors that contribute to flooding in coastal communities. High water levels in the ocean and in sounds cause the groundwater table to rise, which limits the ability for stormwater to soak into the ground. This increase in the groundwater table can also lead to water filling ditches, and in some cases, infiltrating through cracks in underground pipes, filling stormwater networks. High wind can also contribute to flooding as water blown in from high winds can pile up in tidal creeks and along low shorelines in sounds. Lastly, coastal communities can be flooded during extreme events like hurricanes or tropical cyclones, when storm surge and high waves can lead to overtopping of low shorelines.

In this fact sheet, the term “tidal flooding” will be used to describe all floods in which saltwater temporarily overflows onto normally dry land due to tides, outside of extreme events.

Why Are Tidal Floods Happening, and How Can They Be Reduced?

Why were outfalls and ditches not constructed to avoid being submerged or filled with saltwater from the ocean, sounds, or tidal creeks? In most coastal communities, stormwater management systems were constructed decades ago when sea levels were lower. Since that time, sea levels have risen globally, and in many areas, the land has also been gradually sinking, or subsiding. Now, many stormwater systems are not working as originally designed, and are submerged regularly even during moderate tides due to sea level rise. Across the continental US, average sea levels rose about 0.92 feet from 1920 to 2020. Sea levels will continue to rise at an increasing rate in the future. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predicts sea levels along the continental US will rise an additional 0.82 to 0.98 feet from 2020 to 2050, which is about the same amount of sea level rise over a 30-year period that occurred during the last 100 years. Rates of sea level rise are even greater along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, meaning communities in these areas are some of the most vulnerable in the country to floods driven by sea level rise. Over 60 million people live in coastal counties on the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, which amounts to 18.5 percent of the US population.

As sea levels rise, the average tide levels also rise, filling ditches and submerging outfalls more frequently. Consequently, compound and tidal floods are occurring more often in coastal communities. For example, in Beaufort, North Carolina, NOAA reports there were a total of nine flood days from 1982 to 2002 and a total of 58 flood days from 2002 to 2023, with ten flood days per year in both 2022 and 2023. These flood days did not occur only because of tides; the increasing frequency of flood days in recent years was largely attributed to rising sea levels. In Beaufort, NOAA predicts there will be 35 to 125 flood days annually by 2050; the wide range in predicted flood days results from there being several plausible future sea level rise scenarios influenced by factors such as greenhouse gas emissions. Predictions of the number of future flood days from tidal flooding are a “best case” scenario because they do not account for nontidal factors such as rain, groundwater, wind, or stormwater infrastructure. These predictions are also made using water levels measured at tide gauges, which are sparsely located along the coast. When considering these factors, it is known that the real number of flood days will be higher in most coastal communities than the predictions at the tide gauges suggest.

Even if communities want to move or enlarge their pipes and ditches in preparation for future sea level rise, they may face obstacles. First, many coastal areas, particularly in the South and Mid-Atlantic region, are flat and low-lying; this means there is little change between the elevation of the road and the elevation of outfalls. Second, these types of construction projects are very costly and disruptive, and many communities do not have the funds or resources for projects of this scale. The cost may also be difficult to justify because sea levels will continue to rise to the point that tidal floods will eventually be driven more by overtopping of low-lying shorelines and groundwater than faulty stormwater networks (Habel et al., 2020). Therefore, to minimize flooding, any changes to the configuration of stormwater networks will likely need to be accompanied by other infrastructure improvements (for example, construction of bulkheads, raising other infrastructure).

To minimize future increases in compound and tidal flooding from sea level rise, the causes of global climate change will have to be addressed, but addressing global climate change requires large-scale, international collaboration. This fact sheet provides short timescale options for local communities and landowners to address tidal flooding today.

Tide/Flap Gates

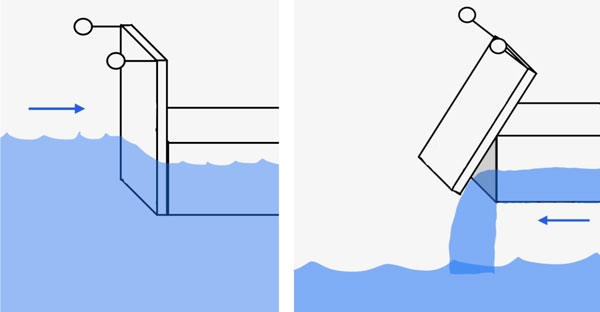

Flap gates, also referred to as tide gates, are door-like structures on the outfalls of drainage pipes and ditches (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4). Some flap gates are hinged on the side and open like a door, while others may be connected at the top of the outfall structure (Figure 3, Figure 4).

Flap gates open and close based on the water levels on either side of the gate. When there is water flowing within the pipe at a level that is sufficiently higher than the water on the outside of the pipe, the gate is pushed open, letting water drain from the pipe into the ocean or sound. When water is not flowing within the pipe or if ocean/sound water submerges the gate at a level higher than the water in the pipe, the gate stays closed and blocks water from entering the pipe from the ocean or sound. When a flap gate opens and closes solely based on water levels on either side of the gate, it is referred to as “self-regulating.” An advantage of self-regulating flap gates is they do not require an outside power source, so they can be installed in remote locations. The main disadvantage of self-regulating flap gates is they can get blocked by trash, debris, or biological growth (for example, oysters), and consequently be lodged open or closed depending on how the gate gets stuck. Routine and post-storm inspections and maintenance are key to ensuring flap gates perform as intended. At the end of this fact sheet, maintenance considerations are offered for each of the devices.

Not all flap gates are self-regulating. Some flap gates use a computer-based system that controls when the gate opens and closes. The control system might consider information from sensors, such as water-level sensors and/or rain gauges, or can be programmed to open and close based on a schedule. The control system programming can be modified on an as-needed basis, such as to prepare for a major storm. Computer-controlled flap gates have the advantage of being tailored to a specific community’s needs. For example, a computer-controlled tide gate could be programmed to close only if salinity or water level exceeds a threshold. When installed in another community, the same gate may be programmed to close for a different salinity or water-level threshold. Computer-controlled gates, however, have the disadvantages of requiring (1) an external power source, which can be challenging to access in many locations, (2) substantial funds, as these systems can be costly, (3) skilled personnel with knowledge of control systems, because the user may need to program the control system themselves, and (4) increased maintenance.

Additionally, for both self-regulating and computer-controlled flap gates, the gate material and hardware (usually metal) can corrode over time, particularly in saltwater. Flap gates can also prevent stormwater from draining when sea or sound water levels are high enough to cover the gate, which could cause the pipes to fill with stormwater runoff to the point of flooding. Therefore, it is important to consider the difference in water level needed between the “rainfall” and tidal “sea” sides of the gate for the gate to lift and release the impounded stormwater. Accordingly, flap gates can be effective at reducing tidal flooding, but cannot eliminate compound floods. But the gate may not worsen compound flooding because it prevents tidal waters from entering the pipe or ditch, which can preserve some storage space within the stormwater management system.

Sluice Gates

A sluice gate is a specific type of tide gate that is vertically raised or lowered to block the exit of a drainage pipe or channel and reduce tidal flooding (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Sluice gates are similar to flap gates, except they are not self-regulating. They are typically manually opened and closed, but some can be operated with computer-based controls. The main advantage of a manually operated sluice gate is that the operator has total control and decides when it is opened or closed. But the need for an operator is also the primary disadvantage, because that person will have to monitor changes in water levels to determine when the gate should be closed or opened. Computer-controlled sluice gates have the same disadvantages as computer-controlled tide and flap gates. Additionally, as with tide and flap gates, the metal material of the sluice gate can corrode over time, and closed gates can prevent stormwater drainage. Sluice gates should be regularly greased and maintained.

Duckbill Check Valves

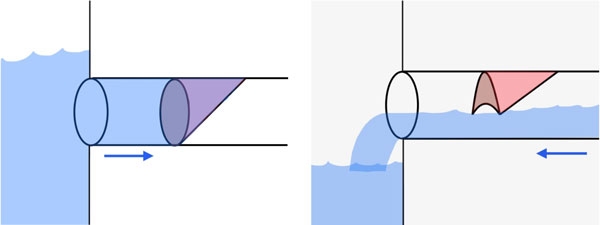

A duckbill check valve is made of rubber, has a curved bill, and is installed at the end of a pipe outfall (Figure 7 and Figure 8). When water is not flowing out through the pipe or when the ocean level is higher than the duckbill, the curved bill stays closed, preventing sea or sound water from coming in. When ocean or sound water levels are below water levels within the pipe, the duckbill will gradually open, allowing drainage.

Duckbill check valves do not require an outside power source, are mechanically simple and made of noncorroding material, and can be effective at reducing tidal flooding and the severity of compound floods. They are unable, however, to eliminate compound floods altogether. Duckbill check valves are designed to close even if there is small debris present in the duckbill, making them less susceptible to blockages than flap gates. Duckbill check valves can still be held open, however, by larger debris or biological growth if they are not regularly cleaned. Additionally, to open and allow stormwater drainage, there needs to be an adequate difference in water levels between the stormwater and tidal “sea” sides of the duckbill check valve. The difference in water levels required for the bill to open should be included in manufacturer specifications. It is important to consider the specifications of the duckbill check valve in relation to expected rain and tide levels to determine its suitability.

Inline Check Valves

An inline check valve is installed inside of a pipe instead of on the end of the outfall. There are several different types of check valves. One type uses a cone device (Figure 9 and Figure 10), where the opening of the cone faces the outfall. When water enters the pipe at the outfall and arrives at the cone, the valve blocks the water from moving further up the pipe to prevent backflow and reduce tidal flooding. When stormwater comes from the other direction, the edge of the cone is pushed up and creates an opening the water can flow through. Watch a video demonstrating how this type of check valve works. (Note that this video was prepared by a check valve manufacturer. This is not an endorsement of any specific manufacturer’s products.) Other check valves do not use the same cone structure, but similarly prevent backflow within a pipe.

Because check valves are installed inside pipes, multiple check valves can be placed along the length of a pipe and/or in addition to a device at the outfall, such as a flap gate. The check valves can also be placed strategically, such as next to a flood-prone stormwater drain. As a result, one of the main advantages of check valves is that they can act as back-up measures to outfall-based flood reduction devices, and they can be used with greater precision than devices installed at outfalls. When they are installed inside of pipes, however, they are more difficult and costly to install and maintain than devices installed at outfalls. When access to a check valve is limited, safety can become a concern; refer to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) for specific guidance on how to navigate such risks. Some installations have placed check valves at outfalls so they can be accessed more safely and easily. Similar to duckbill check valves, inline check valves are made from noncorroding material, but debris and biological growth can compromise functionality by keeping the valve from closing completely.

Pumps

In some communities, gates and valves may not be possible to install or may insufficiently reduce flooding. In these areas, additional measures such as pumps may be needed to move floodwaters to the ocean, sounds, tidal creeks, storage reservoirs, or other stormwater networks. Mobile pumps can be transported to a location and used after a flooding event. Other pumps can be permanently installed in areas where flooding often occurs. For example, the Town of Emerald Isle, NC, has both mobile and permanently installed pump stations. Pumps can sometimes be installed within a drainage system to avoid flooding. This is a strategy used by the City of Washington, NC, on Jack’s Creek.

The main advantage of a pump system is that it can provide quicker relief from tidal or compound flooding and act as a back-up measure to gates and valves. Disadvantages include high installation cost, maintenance, and energy costs to operate the pump, plus the need for an external power source.

In many places, pumps may not prevent flooding from occurring, and will instead be used in response to floods that have already occurred. But pumps that can move both surface water and groundwater may help lessen flood durations and peak levels by lowering water levels in drainage pipes or channels before an impending event, like a major storm or predicted king tide.

It is also important to consider how pumping might affect other waterways. For example, in 2020, the Town of Emerald Isle pumped floodwaters caused by excess rain into the ocean and sound, and the NC Department of Environmental Quality issued precautionary swimming advisories for nearby beaches due to water quality concerns.

What Else Should Be Considered Before Installing a Flood Reduction Device?

Devices are not permanent solutions. Although these devices can be helpful in reducing the severity of tidal and compound flooding over several years, they are not permanent flood solutions. Flood reduction devices should be installed while also creating comprehensive and long-term (10+ years) sea level rise adaptation plans. When selecting a flood reduction device, consider not only the performance of the device at current sea levels, but also the performance of the device at future sea levels corresponding to the lifespan of infrastructure to be protected.

Multiple devices are needed to reduce community-scale tidal flooding. Ditches and underground stormwater pipes are often interconnected. If one pipe or ditch outfall is retrofitted with a device, tidal waters may still create flooding if a connected pipe or ditch is not also retrofitted with a device. Consider all connection points and sources of saltwater to an area when determining how many devices are needed to reduce flooding. One should consider the topography of the surrounding area and identify all flow channels that contribute to tidal flooding. Each potential flooding pathway (the lowest elevation areas that are the paths of least resistance for floodwaters) must be considered in selecting the location for device installation.

Devices are vulnerable to biofouling. All these devices are vulnerable to biofouling, which is a term used to describe the growth of marine plants and animals such as bivalves, barnacles, and algae (Figure 11). Biofouling can inhibit devices from opening and closing as designed; therefore, growth must be routinely removed from devices to ensure they work properly. Oysters are particularly harmful to the function of flood reduction devices such as flap gates and duckbill or inline check valves. In some cases, if biofouling becomes too severe, the device may need to be replaced. Although manufacturers may advertise that some devices need little maintenance or are not vulnerable to biofouling, communities that have installed these devices often report otherwise. The frequency with which devices should be inspected will vary by site, but devices will likely need to be visited at least quarterly to remove debris and/or biofouling. Keep in mind that biofouling is often worse in summer, when higher temperatures promote biological growth.

Devices require maintenance. Before investing in a device, create a maintenance schedule, estimate maintenance costs, and establish access plans for devices installed along the edges of waterways or marshes. Refer to manufacturer guidelines for specific maintenance actions to be taken, such as routine greasing. Consider budgeting for additional devices and parts in the event a replacement is needed.

Devices should be well sealed. When installing a flood reduction device, it is critical that the device is well sealed within the pipe or channel, and the seal should be inspected for cracks during routine maintenance. If the device is not well sealed, water may infiltrate around the device, reducing or eliminating the device’s ability to alleviate flooding.

Devices may require permits or special permissions for installation. Before installing any flood reduction devices, landowners should consult with their local government offices to assess permitting needs, and to determine whether they may infringe on others’ property and drainage rights through the installation of a device. Some ditches and channels may be classified as jurisdictional water features that are subject to the Clean Water Act Section 404 rules.

Devices may not reduce compound flooding. Devices designed to reduce tidal flooding will also prevent stormwater from freely draining out of stormwater management systems, which could cause compound flooding. In communities facing severe compound flooding, management actions are likely needed in addition to flood reduction devices, such as creating additional stormwater storage.

Acknowledgments

Hanna McCormick created all flood reduction device illustrations. Special thanks to Johnny Martin of Moffatt & Nichol for reviewing an early draft of this document and Daniel Keating of the Town of Carolina Beach for providing input on device installation and maintenance. Members of the team that prepared this fact sheet are supported by U.S. National Science Foundation award 2047609 and NC Collaboratory grants 388 and 535.

References

Gold, A., K. Anarde, L. Grimley, R. Neve, E. R. Srebnik, T. Thelen, A. Whipple, and M. Hino. 2023. “Data from the Drain: A Sensor Framework that Captures Multiple Drivers of Chronic Coastal Floods.” Water Resources Research 59: e2022WR032392. ↲

Habel, S., C. H. Fletcher, T. R. Anderson, and P. R. Thompson. 2020. “Sea-Level Rise Induced Multi-Mechanism Flooding and Contribution to Urban Infrastructure Failure.” Scientific Reports 10: 2796. ↲

NOAA. 2022. “The State of High Tide Flooding and 2022 Outlook.” Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services, National Ocean Service. Accessed June 20, 2023. ↲

Sweet, W. V., B. D. Hamlington, R. E. Kopp, C. P. Weaver, P. L. Barnard, D. Bekaert, W. Brooks, M. Craghan, G. Dusek, T. Frederikse, G. Garner, A. S. Genz, J. P. Krasting, E. Larour, D. Marcy, J. J. Marra, J. Obeysekera, M. Osler, M. Pendleton, D. Roman, L. Schmied, W. Veatch, K. D. White, and C. Zuzak. 2022. “Global and Regional Sea Level Rise Scenarios for the United States: Updated Mean Projections and Extreme Water Level Probabilities Along U.S. Coastlines.” NOAA Technical Report NOS 01. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Ocean Service, Silver Spring, MD. 111 pp.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2019. “Coastline America.” ↲

Other Resources

NOAA National Ocean Service: Is sea level rising?

NOAA National Ocean Service: What is high tide flooding?

NOAA: Understanding Stormwater Inundation

NASA: Sea Level Change Team Flooding Analysis Tool

NOAA: Annual and Monthly High Tide Flooding Outlook

Contact

Natalie Nelson, nnelson4@ncsu.edu, 919-515-6741

Publication date: Jan. 28, 2025

AG-979

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.