A community garden can help transform people who happen to live in the same place into a united community. It celebrates diversity in individual plots while creating opportunities for people to work together and learn from each other—about gardening, food preparation, and more. They learn to respect each others’ differences and to appreciate what they have in common. Community gardens build relationships that last beyond the growing season.

In addition, community gardens lead to a more livable environment, creating beauty and reducing crime (Hynes, 1996; Warner and Hansi, 1987), increasing home values (Been and Voicu, 2006), and improving the image of the community (Been and Voicu, 2006). The skills learned in developing the garden can be used to gain access to public policy and economic resources, which can then help address critical problems such as crime, homelessness, and urban blight (Armstrong, 2000).

Benefits of Community Gardens

In addition to providing fresh fruits and vegetables, a garden can also be a tool for promoting physical and emotional health, connecting with nature, teaching life skills, and promoting financial security.

Health: Community gardens provide a place to grow healthy, nutritious food resulting in both gardeners and their families eating a wider variety, larger quantity (Alaimo, Packnett, Miles, and Kruger, 2008), and higher quality of fresh fruits and vegetables. In addition, gardeners increase their physical activity and overall health (Wakefield, Yeudall, Reynolds, and Skinner, 2007).

Nature: For many urban dwellers surrounded by high-rise buildings and concrete, a community garden may provide the only contact with plants, birds, butterflies, and nature. Lessons learned in the community garden about water conservation, water quality preservation, environmental stewardship, and sustainable land use may be taken back to homes, businesses, and schools and implemented, improving environmental health.

Life Skills: In addition to a wealth of basic horticulture information, gardeners learn important life skills such as planning, organization, and teamwork.

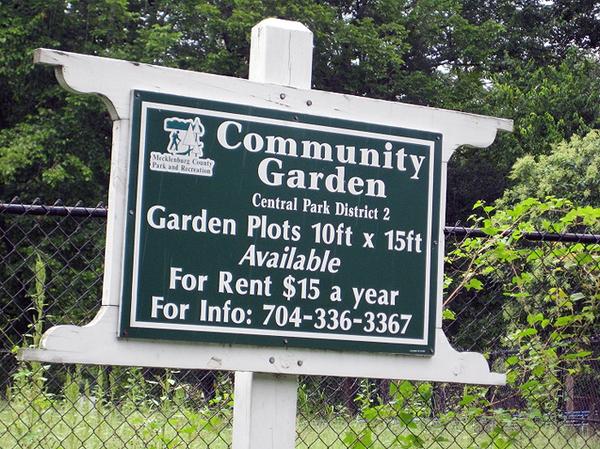

Finance: Community gardens may have financial benefits for both the gardener and the landowner. Some gardeners sell the produce they grow. Others benefit by reducing the amount they spend on produce. Property owners may generate income by renting garden plots.

Participating in a community garden improves the health of the gardener, as well as his or her family, the community, and the environment.

Types of Community Gardens

Community gardens are as varied as the neighborhoods in which they thrive. Each is developed to meet the needs of the participants who come together on common ground to grow fruits, vegetables, flowers, herbs, and ornamental plants. Community gardens can be found at such diverse locations as schools, parks, housing projects, places of worship, vacant lots, and private properties.

While all these gardens serve as catalysts for bringing people together and improving community, some of them focus on growing food for the gardeners themselves. Others donate their produce to the hungry. Some focus on education, some on nutrition and exercise, still others on selling produce for income. Some simply provide a venue for sharing the love of gardening. All community gardens provide opportunities for neighborhood renewal and beautification.

Types of Community Gardens

- Plot Gardens (divide into individual plots)

- Cooperative Gardens (work as a team on one large garden)

- Youth Gardens

- Entrepreneurial Market Gardens (sell produce)

- Therapeutic Gardens

Plot Gardens: One familiar strategy is to subdivide the garden into family-sized plots ranging in size from 100 to 500 square feet. Sometimes a section of the garden is reserved for the community to grow crops too large for individual plots (corn, pumpkins, watermelons, fruit trees, grapes, berries). Gardeners divide the bounty from these shared plots. (See a design of a typical plot garden in the appendix). On a quarter-acre lot, there is room for approximately 35 garden plots, each 10 feet × 20 feet separated by three-foot-wide pathways.

Cooperative Gardens: In a cooperative garden, the entire space is managed as one large garden through the coordinated efforts of many community members. Produce from the garden is sometimes distributed equitably to all the member gardeners. Often these gardens are associated with communities of faith, civic groups, or service organizations that donate part or all of the produce to charitable organizations such as food banks and soup kitchens.

Youth Gardens: With the increasing interest in science and nutrition education, many primary schools in the United States are planting gardens to serve as outdoor learning laboratories. In the garden, everyone is transformed into a scientist, actively participating in research and discovery. Besides providing a motivating, hands-on setting for teaching skills in virtually every basic subject area, the garden is a wonderful place to learn responsibility, patience, pride, self-confidence, curiosity, critical thinking, and the art of nurturing. Usually, raised-bed gardens, or a section of the school landscape, are assigned to classes. Hands-on curricula and activities are selected to supplement and support the standard course of study for science and nutrition for specific grade levels. In some cases, school gardens require extensive volunteer support so that classes may be split into small groups of children to work in the garden.

Entrepreneurial Gardens: Gardeners, young and old, learn business principles and skills by growing and selling produce for local markets and restaurants. Many children have no idea where food comes from before it arrives in the supermarket. They have never seen a garden and have no skills in growing food. At entrepreneurial market gardens, youth learn not only how to grow food but also how to sell it at local farmers’ markets or grocery stores. As in 4-H, a leader guides the team through the entrepreneurial process that begins with planning the garden and ends with selling the produce.

Therapeutic Gardens: Still other gardens focus on horticulture therapy, using plants to improve the social, educational, psychological, and physical well being of the gardeners and their caregivers, family, and friends. Located in hospitals, nursing homes, assisted living facilities, retirement communities, outpatient treatment centers, botanical gardens, and other settings, therapeutic gardens are generally designed to be accessible to people with physical limitations. They may include raised beds and firm pathways to provide access to participants in wheelchairs, Braille signage for blind gardeners, special tools for gardeners with limited physical strength, and other accommodations. Therapeutic gardens may be designed for active gardening programs or as a quiet space for reflection.

Each of these types of community gardens has different goals and strategies for success. This guide will focus on community gardens with individual family-sized plots, outlining the steps in organizing a community garden.

How to Start a Community Garden

As creating a community garden is a substantial project requiring sustained effort over several years, it takes a strong commitment from at least three to five individuals to create and manage a successful garden. Just because you build it, doesn’t mean they will come. In fact, seldom is a garden that was designed and built by outsiders adopted and sustained by a community. Engage the community from the beginning.

Many types of organizations sponsor community gardens. Any of the following groups may have land, resources, and interested employees or clients.

- Churches

- Citizens’ groups

- Colleges and universities

- Community and senior centers

- Community service/development organizations

- Cooperative Extension

- Food banks

- Health departments

- High-density housing developments

- Housing and social service authorities

- Municipalities

- Neighborhood associations

- Parks and recreation

- Private businesses

- Railroad and transit lines

- Retirement communities

- Schools

Begin by identifying who will be gardening. Will it be youth, families, seniors, a special population, or people in a specific geographic region? All your decisions will be driven by the goal of meeting the specific needs of the gardeners.

Form a planning committee and make preliminary decisions

Include those who will be gardening, nearby residents, and potential partners. Identify and invite leaders within the community and other interested people to an organizational meeting and social gathering. Including food at events is always a plus. Develop a well-organized leadership team with committees assigned to specific tasks (for example: recruitment, partnership development, special events, garden organization). Develop bylaws (see appendix) that clarify the purpose and objectives of the garden. Determine how decisions will be made and what process will be used to select leaders. Clarify how work will be shared and who will be responsible for what. Decide on the scope of garden including the size and the components (fruit trees, berries, shared community plot for large crops). Make management decisions including whether there will be any restrictions on the use of pesticides and fertilizers. Choose a name for the garden.

Create a prioritized budget and a wish list of desired donations and update it regularly (see appendix). Identify how you will raise money (membership dues, fund raising, grants, sponsors).

Consider the need for insurance as well as potential sources and costs. Explore whether any of your partnering organizations can provide insurance for free or at a minimal cost. Many landowners require liability insurance, but many insurance carriers and their underwriters are reluctant to cover community gardens. Consider working with a firm that represents many different carriers, and get at least one quote from one of the ten largest insurance carriers.

Identify potential partners, sponsors, or funders

Seek out donations of money, labor, land, soil amendments, tools, seeds, plants, fencing, and supplies. Above is a list of potential partners. See the sample budget and the potential funding sources in the appendix. To build effective relationships with partners, donors, or funders it is useful to track several kinds of information: 1) contact information; 2) actual contacts (who from the garden contacted whom); 3) when contacted, with what request, what was the outcome; 4) gift history (what have they donated to the garden in the past). See the appendix for a sample tracking form.

Choose a site

Clean water, healthy soil (local or imported), six hours of sunlight per day, and a location in which gardeners feel safe are essential to success. The site should be convenient to the intended audience. There should be easily accessible, clean, and affordable irrigation water available. Once you have found a suitable lot, identify the land owner to see if he or she is interested. If possible, obtain a list of previous uses of the land to evaluate potential contamination. Do a soil test to identify the existing nutrient level and ensure the absence of heavy metals.

Negotiate a lease or written agreement that allows the space to be used as a community garden for at least 5 years. In the written agreement clearly identify:

- who is responsible for providing water and security

- what liability insurance is required

- what fee, if any, will be required and when it is due

- who will be responsible for clearing the property to prepare it for gardening

- what, if any, resources the owner will be providing

- what would be grounds for terminating the contract (vandalism? weeds?)

- who the primary contact for the garden and the property owner will be and their contact information.

Community and senior centers, where people gather with the expectation of taking part in organized activities, have excellent potential as community garden sites. Becoming involved prior to construction increases the likelihood of space being reserved on site for gardening.

Vacant lots are widely available in large cities. Often city officials are happy to save money by having someone else take care of the property. Check with your local planning and zoning departments for leads. Do not plant an edible garden in the floodplain. Stormwater can wash in biological contaminants like sewage from flooded septic tanks and chemical pollutants from a variety of sources.

Organize the garden

Establish criteria for membership in the garden: for example, residence in a specific geographic region, payment of dues, agreement with rules, and participation in upkeep of common areas. Identify the selection process for initial gardeners and for gardeners chosen to fill vacancies. Determine a strategy for assigning plots (family size, residency, need, order of requests). Specify how maintenance of the common areas of the garden will be managed (weeds, irrigation, tools, compost piles). Spell this out in bylaws and the memorandum of understanding. (See appendix.)

Identify how dues (if collected) will be used and what services, if any, will be provided to gardeners in return. If you decide to obtain communal tools, hoses, and supplies, identify how they will be stored and distributed. Decide how often the gardeners will be expected to participate in group workdays. Schedule group projects, workdays, and pot lucks. Social events enhance the success of the garden. Consider the pros and cons of forming a non-profit organization and working toward owning the garden site.

Keep governance simple and responsive. In the beginning (and even later for small gardens), an informal structure may be all you need. As the number of people and the workload expands, a more formal structure may enable each gardener to participate fully and the group to perform effectively. Structure can promote stability, trust, and a foundation for growth. It also provides a framework within which new leaders can be cultivated.

Some potential recruiting strategies include:

- contacting community organizations such as churches and schools

- posting flyers

- advertising through local media

- connecting with residents who can help spread the news.

Developing written bylaws is an excellent process for being sure that the planning committee agrees about expectations for members and officers as well as consequences for not following the rules. It is also useful in communicating these to the members. If enforcement becomes necessary, the steps are clear and fair application is transparent. See the sample in the appendix and review samples from organizations that you respect.

Many gardens find it useful to have a Memorandum of Understanding signed by each gardener. See the sample in the appendix. This document clearly identifies all of the requirements, timelines, and consequences for not adhering to the rules.

Develop the garden

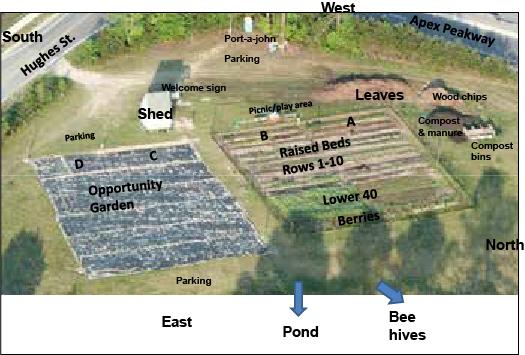

Create a garden plan with plot size(s) and location. Reserve space in the plan for all of the components you hope to eventually add in the garden, even if you do not currently have the resources to install them. Consider including storage sheds, compost bins, picnic tables and gathering space, a rainproof bulletin board, a children’s plot, ornamental perimeter plantings (for curb appeal), and an irrigation system (see the appendix for a sample garden design). Wide pathways make for good neighbors. A minimum of three feet is necessary to allow for wheelbarrows and carts to pass by plots without damaging plants.

Plan community workdays to remove existing rubbish and weeds, lay out the beds, and prepare the soil. Install an irrigation system if desired. This might include installation of 1-inch PVC pipe placed underground which connects to conveniently located spigots and/or drip irrigation for individual beds. Consider freeze-proofing the plumbing to prevent the expense and inconvenience of flooding if the pipes burst.

Install a sign with contact information and a bulletin board to share educational information, meeting notices, contact information, and tasks.

Potential Problems and Solutions

No topsoil

Many potential garden sites in communities and schools had the topsoil removed during grading or have been built on “fill” materials. If this is the case, raised beds with imported topsoil may be needed. Beds should be 12 to 24 inches deep.

Weeds

Prevention: In the memorandum of understanding, specify weed management requirements for personal plots, pathways, and community areas. Assign all plots in the garden so none are left untended for weeds to spread. Encourage the use of mulch around plants to minimize the soil surface area available for weeds to grow.

Management: Intervene early. The smaller the weed, the easier it is to remove. By removing weeds before they flower and set seed, you prevent the next generation. Have a work day and encourage gardeners to work together to remove weeds.

Angry neighbors

Prevention: Specify in bylaws how the plots must be kept and the consequences for not complying. Enforce the bylaws. Work at building a positive relationship with neighbors.

Management: Meet with the neighbors in person to clearly identify their concerns, and if well founded, explain how you intend to address them. A well-organized garden with strong leadership and committed members can overcome almost any obstacle.

Arguments between gardeners

Prevention: Make pathways at least three feet wide. This minimizes the possibility of damaging plants when passing by with a wheelbarrow or cart. Stake the corners of the plots to prevent hoses from being dragged across plants. In the memorandum of understanding clearly state any restrictions on fertilizer and pesticide uses. Consider setting aside part, or all, of the garden as either organic or pesticide-free. Group all plots designated as organic or pesticide-free to minimize the potential for chemical drift from other gardeners’ plots. Manage weeds. Enforce the bylaws and the memorandum of understanding.

Management: Engage those involved in identifying issues and potential resolution. Handle issues before they escalate.

Abandoned plots

Prevention: Include in the memorandum of understanding clear expectations for how the plot is to be maintained and the process for reassigning the plot as a consequence of failure to comply.

Management: Charge an initial deposit that can be used to cover the cost of cleaning up abandoned plots.

Theft

Prevention: Designate a plot near the entrance for people to “help themselves.” Put up a sign inviting them to harvest from this, and only this, plot. Plant potatoes, other root crops, or less popular vegetables such as kohlrabi along the sidewalk or fence. Plant the purple varieties of cauliflower and beans or white eggplants to confuse vandals. Rather than purchasing fancy new hoses, get old hoses donated. Old hoses are rarely stolen. Encourage gardeners to plant more than they will need to prepare for potential loss. Recruit garden neighbors to keep an eye out for and report intruders.

Management: Keep gardeners and neighbors informed.

Vandalism

Prevention: Put up a sign identifying the garden as a neighborhood project. Raised beds may prevent trampling. Be inclusive. Develop a shared vision and ownership of the garden. Nurture relationships with neighbors and community residents. Request their assistance in keeping a protective eye out over the garden. Establish children’s plots within the garden and invite young people within the community to participate. Consider marketing the youth plots to local scout troops, day cares, foster grandparent programs, and church groups to increase the number of people in the garden and decrease the amount of time it is vacant. Consider offering free small plots in the children’s garden to the children of community gardeners. Create a comfortable shady meeting area in the garden and encourage gardeners and neighbors to spend time there. Harvest all ripe fruit and vegetables on a daily basis. Red tomatoes falling from the vines are hard to resist. Hold meetings and encourage others to hold meetings and social events in the garden. Install a fence. This will not keep out someone who is determined to come in. However, it clearly marks possession of a property and will keep out dogs. Plant raspberries, blackberries, roses, or other thorny plants along the fence as a barrier to climbing.

Management: Take time to allow the gardeners to reflect on the experience and share ideas on how to prevent future vandalism.

The keys to a successful community garden of individual plots include forming a strong planning team, choosing a safe site accessible to the target audience with sunlight and water, organizing a simple transparent system for management, and designing and installing the garden. Even with all of these strategies, it is possible to have problems. Address them quickly and fairly before tensions build.

Appendices

Garden Design — Sample layout for plot garden

Bylaws — Suggestions for what to include in by-laws

Gardener Application — Sample application for a garden plot

Gardener Memorandum of Understanding — Minimize conflict by spelling out the expectations in writing and having each gardener sign the document

Budget — List of items you may want to include in your budget; and Strategies for Tracking Funders — Tips for organizing fund development information

Resources and Funding for Gardens — Some ideas on where to go for support

Resources — Other sources of information

References

Alaimo, K., E. Packnett, R.A. Milesand, and D. J. Kruger. 2008. Fruit and Vegetable Intake among Urban Community Gardeners. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 40: 2, 94-101.

Armstrong, D. 2000. A Survey of Community Gardens in Upstate New York: Implications for Health Promotion and Community Development. Health & Place 6: 319-327.

Been, V. and I. Voicu. 2006. The Effect of Community Gardens on Neighboring Property Values. New York University School of Law, New York University Law and Economics Working Papers, Paper 46.

Draper, C. and D. Freedman. 2010. Review and Analysis of the Benefits, Purposes, and Motivations Associated with Community Gardening in the United States. Journal of Community Practice 18: 4, 458-492.

Hynes, H.P. 1996. A Patch of Eden. Chelsea Green, White River Junction, VT: America’s Inner-City Gardeners.

Malakoff, D. 1995. What Good is Community Greening? American Community Gardening Association Monograph. Philadelphia.

Van Den Berg, A.E. and M.H. Custers. 2011. Gardening Promotes Neuroendocrine and Affective Restoration from Stress. Journal of Health Psychology 16:3-11.

Wakefield, S., F. Yeudall, C. Taron, J. Reynolds, and A. Skinner. 2007. Growing Urban Health: Community Gardening in South-East Toronto. Health Promotion International 22: 2, 92-101. Oxford University Press.

Warner, S.B. and D. Hansi. 1987. To Dwell Is to Garden: A History of Boston’s Community Gardens. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation to Keith Baldwin, Don Boekelheide, Karen Neill, Liz Driscoll, Julie Sherk, Brantley Snipes, Amy Hill, Viki Balkcum, and Karl Larson for their contributions to this project.

Publication date: June 17, 2019

AG-737

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.