Weed management must be an ongoing consideration for organic farmers to achieve acceptable yields and crop quality. A system of weed management that includes multiple tactics will help reduce losses in both the short and long term. Various weed management strategies fall into two major categories: cultural and mechanical. Cultural practices are associated with enhancing crop growth or cover, while mechanical practices are used to kill, injure, or bury weeds. During a cropping season, successful organic weed management will rely on the cultural practices described below to achieve competitive crop plants, and will use the mechanical practices to reduce the weed population that emerges in the crop.

Cultural Tactics

Crop Rotation

It is beneficial to rotate crops with different life cycles, growth patterns, and management techniques. A diverse crop rotation is important for mitigating pests and disease in organic systems, as well as reducing weed pressure. A crop rotation that is diverse will reduce opportunities for weeds to become prolific over successive years through increasing competition. For example, a rotation could include a summer crop, winter crop, legume, grass, a cultivated crop (corn), and a non-cultivated crop (wheat or hay).

Variety and Cover Crop Selection

Some varieties may be more competitive than others, and selecting a variety with growth habits that are competitive can improve weed suppression. Tall varieties and varieties with rapid establishment and quick canopy closure are more competitive with weeds than short or dwarf varieties, or varieties (or seedlots) that have low seed vigor, are slow growing, or are less bushy. Some weed species are suppressed by crop-produced allelochemicals (naturally produced compounds that can inhibit the growth of other plants) in standing crops or in residues of allelopathic crops (such as a rye cover crop). Results of studies conducted with wheat and rye have demonstrated that the production of allelochemicals varies widely with cultivar and can change in concentration during crop development.

Seed Quality

Seed cleanliness, percent germination, and vigor are characteristics that can influence the competitive ability of the seedlings. Seed that has not been carefully screened (especially farmer-saved seed) is often of lower quality than certified seed and may contain unknown quantities of weed seed or disease. Planting this seed may result in the introduction of pests not previously observed on the farm. There is also a risk that weed density will increase and that weeds will be introduced to previously uninfested parts of the field. Germination rate and vigor are equally important to weed management because they collectively affect stand quality and time to canopy closure.

Planting—Sowing Date, Seeding Rate, Row Spacing, And Population

Sowing date and seeding rate affect the final crop population, which must be optimum to compete with weeds. Carefully maintained and adjusted planting equipment will ensure that the crop seed is uniformly planted at the correct depth for optimum emergence. Narrower rows and increased plant populations will help the crop compete with weeds. When blind cultivation such as rotary hoeing will be used, seeding rates should be increased by 10% to 20%. If a particularly aggressive blind cultivation tactic such as springtooth harrowing will be utilized, seeding rates should be increased to at least 20%.

Cover Crops

Cover crops can provide benefits of reduced soil erosion, increased soil nitrogen, and weed suppression through allelopathy, light interception, and the physical barrier of plant residues. Cover crops such as rye, triticale, soybean, cowpea, or clover can be tilled in as a green manure, allowed to winter-kill, or be killed or suppressed by undercutting with cultivator sweeps, mowing, or rolling. Warm-season cover crops help to suppress weeds by establishing quickly and out-competing weeds for resources. It is important to manage cover crops carefully so that they do not set seed in the field and become weed problems themselves. For hard-seeded cover crops such as hairy vetch, timely termination to avoid seed set may help avoid problems with hairy vetch volunteers in wheat the next season. Additional information on using cover crops to suppress weeds can be found in the “Rolled Cover Crop Mulches for Organic Corn and Soybean Production” chapter of this guide.

Fertility—Compost and Manures

Uncomposted or poorly composted materials and manures can be a major avenue for the introduction of weed seeds. However, soil fertility that promotes early and sustained crop growth helps to reduce the chance that weeds will establish a foothold. Areas of poor productivity leave the door open to diseases, insect pests, and weeds.

Sanitation and Field Selection

Weeds are often spread from field to field on tillage, cultivation, or mowing equipment. Cleaning equipment before moving from one field to another, or even after going through a particularly weedy section, can prevent weeds from spreading between fields or within fields. A short investment of time to clean equipment can pay large dividends if it prevents the spread of problem weeds. When transitioning to organic systems, it is highly advisable to start with fields that are known to have low weed infestations. Fields with problem weeds, such as Palmer amaranth, Italian ryegrass, wild garlic, Johnsongrass, or bermudagrass, should be avoided if possible, as these weed species will be difficult to manage.

Mechanical Tactics

A healthy, vigorous crop is one of the best means of suppressing weeds. However, some physical tactics are almost always needed to provide additional weed control. The methods described below can be used together with good cultural practices to kill or suppress weeds—leaving the advantage to the crop. The goals of mechanical weed control are to eliminate the bulk of the weed population before it competes with the crop, and to reduce the weed seed bank in the field. Important factors to consider for mechanical weed control are the weed species present and their size, soil condition, available equipment, crop species and size, and weather. Since it might not be necessary to use a tactic on the entire field, knowledge of weed distribution and severity can be valuable. Tillage, blind cultivation (shallow tillage of the entire field after planting), and between-row cultivation are important aspects of mechanical weed control.

Tillage

Proper field tillage is important to creating a good seedbed for uniform crop establishment, which is a critical part of a crop’s ability to compete with weeds. Tillage should also kill weeds that have already emerged. In the spring when the soil is warm, weed seeds often germinate in a flush after tillage. A moldboard plow will bury the weed seeds on or near the surface (those that come out of dormancy as the soil warms) and bring up dormant weed seeds from deeper in the soil. These weed seeds will normally be slower to come out of dormancy than weed seeds previously near the surface. Chisel plowing or disking does not invert the soil and can result in an early flush of weeds that will compete with the crop. If there is enough time before planting, the stale seedbed technique can be used as an alternate approach. In this technique, soil is tilled early (a seedbed is prepared), which encourages weed flushes, and then shallow tillage, flaming, or an organically approved herbicide is used to kill the emerged or emerging weed seedlings. While this technique should not be used in erosion-prone soils, it can be used to eliminate the first flush or flushes of weeds that would compete with the crop.

Blind Cultivation

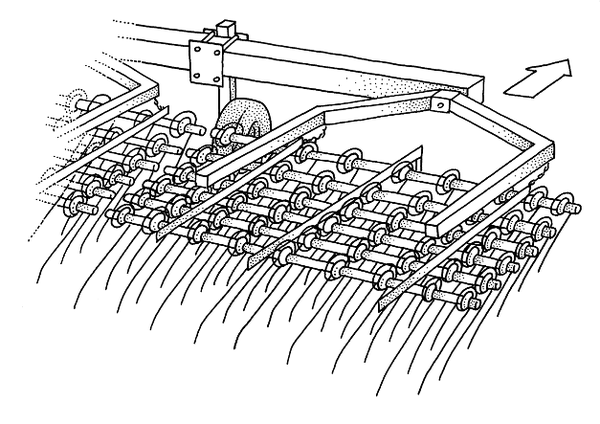

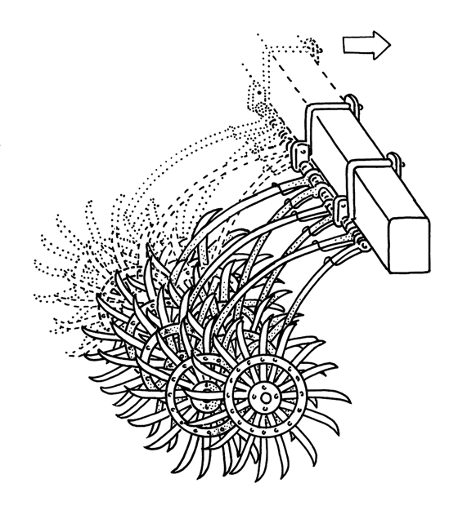

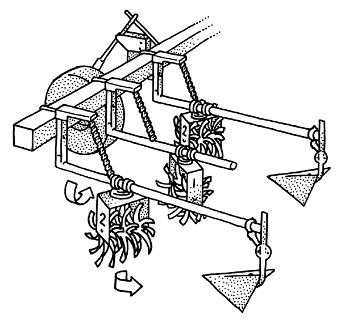

Blind cultivation is the shallow tillage of the entire field after the crop has been seeded. Generally, it is used without regard for the row positions. It provides the best opportunity to destroy weeds that would otherwise be growing within the rows and that are not likely to be removed by subsequent mechanical tactics. Blind cultivation stirs soil above the level of seed placement (further emphasizing the need for accurate placement of the crop seed), causing the desiccation and death of tiny germinating weed seedlings. Crop seeds germinating below the level of cultivation should not be injured. Blind cultivation will only kill weeds in the “white thread” stage. If the weed can be seen from the tractor, it is too large to be destroyed by blind cultivation. Thus, early and timely blind cultivation is critical. However, more than two blind cultivation passes may cause some damage to soybeans. This damage results in decreased yield potential, but blind cultivation is still necessary in order to avoid much higher yield losses from weed competition. The first blind cultivation pass is usually performed immediately before the crop emerges, and subsequent passes approximately every five days afterwards. Blind cultivation cannot be performed when soybeans are in the crookneck stage during emergence. In North Carolina, farmers often need to perform three to five blind cultivation passes, especially in a less competitive crop like soybeans. Blind cultivation is most effective when the soil is fairly dry and the weather is warm and sunny to allow for effective weed desiccation. Blind cultivation equipment includes tine weeders (Figure 10-1), rotary hoes (Figure 10-2), spike tooth harrows, springtooth harrows, and chain link harrows.

Between-Row Cultivation

Between-row cultivation should not be the primary mechanical weed control tactic but should be used as a follow-up tactic to control weeds that escaped previous efforts. Between-row cultivation should be implemented when weeds are about one inch tall and the crop is large enough to not be covered by soil thrown up during the cultivation pass. Usually, more than one cultivation pass is needed. It may be useful to reverse the direction of the second cultivation pass in order to increase the possibility of removing weeds that were missed by the first cultivation. Planting corn in furrows can allow more soil to be moved on top of weeds and may be a useful practice on some farms. All cultivation passes should be done before the canopy closes or shades the area between the rows. After this time, the need for cultivation should decrease, as shading from the crop canopy will reduce weed seed germination and equipment operations can severely damage crop plants. Cultivation works best when the ground is fairly dry and the soil is in good physical condition.

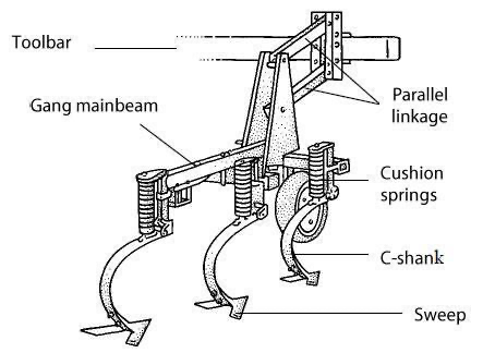

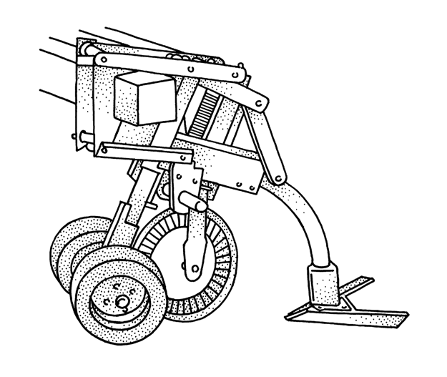

There are many types of cultivator teeth, shanks, and points. Choose the cultivating equipment that works best in your soils. Points for cultivator teeth vary in type and width. Half sweeps (next to the row) and full sweeps (between rows) are probably the most versatile and common, but each type of point works best under certain conditions and on certain weed species. Using fenders on cultivators at the first pass can keep the soil from covering up the crop. Cultivator adjustments are very important and should be made to fit the field conditions. Tractor speed should also be modified through the field to compensate for variability in soil type and moisture.

The different types of between-row cultivators vary in how soil is moved, the size of the weeds that can be killed, and the precision of operation. Rolling cultivators (Figure 10-5) can be fine-tuned to throw precise amounts of soil towards the crop, peel soil away from the crop, or even do both during a single pass. This flexibility makes them a mainstay on most organic farms. S-tine cultivators are also frequently used in combination with rolling cultivators to remove larger weeds. In general, smaller weeds are easier to control than large weeds with one exception. Wide-sweep cultivators that are mounted on parallel linkages have the ability of running parallel to the soil surface. They are able to sever the roots of large weeds and kill them but small weeds are able to reroot. Most wide-sweep cultivators can be angled to control smaller weeds by changing the angle of the blade. They can also throw soil when needed. Examples of low- and high-residue cultivators are presented in Figure 10-3 and Figure 10-4.

Flame Weeding

Flame weeding provides fairly effective weed control on many newly emerged broadleaf species and can be used in tilled or no-till fields. Grasses may not be well controlled by flaming because their growing points are often below the soil surface. Flame weeding should only be performed when field moisture levels are high and when the crop is small. Flame weeding effectively kills weeds by boiling the water within the plant but is limited to early weed development. This management strategy is more time-intensive and limited to targeting small areas. Flame weeding may help organic producers control targeted trouble areas in a field but is most often limited to this scope.

Electric Weeding

Similar to flame weeding, electric weeding kills weeds by boiling water contents of the weed, resulting in plant death. The water contents of the plant will determine the length of time electric contact is needed. Electric weeding is a relatively new option for weed control for organic growers. The “Weed Zapper” and many other electric weeding equipment use a PTO-powered generator which generates between 100,000 to 150,000 watts of electricity.

Hand-Weeding and Topping

Walking fields and hand-weeding or topping (cutting off the weed tops) can vastly increase familiarity with the condition of the crop and distribution of weeds or other pests. Farmers who are familiar with problem locations can remove patches of prolific weeds before they produce viable seeds, and reduce long-term problems caused by weeds that escaped management. Topping of flowering weeds can reduce seed set and the weed seed bank in the field.

Herbicides

Several herbicides have been approved for certified organic farming. These include acetic acid (distilled vinegar), clove oil, nondetergent soap-based pesticides, some corn gluten meal products, and boiling water. The cost of herbicides approved for organic farming may be prohibitively expensive for field crops. The Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI) publishes a list of commercially available products that can be used in certified organic operations for weed control. Conditions for use of an approved herbicide must be documented in the organic system plan as specified in the National Organic Plan.

*Illustrations by John Gist were reprinted with permission from Steel in the Field, published by the Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) outreach office, USDA. Citation of SARE materials does not constitute endorsement by SARE or USDA of any product, organization, view or opinion. For more information about SARE and sustainable agriculture, visit the Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education website.

Managing Weeds Through Diverse Rotations

A farm on 1,700 acres of certified organic land has been growing organically since 1997, when the National Organic Program first began. Most of the fields are soil that is classified as Candor sand, with some other pockets of different soil types, primarily loamy sands. Organic production includes small grains (wheat and rye), tobacco, soybean, and sweetpotato.

Diversifying rotations is a key part of the operation’s strategy for suppressing weeds through competition and minimizing pest and disease pressure.

A typical rotation can include tobacco, a summer cover crop mix, sweetpotato, and soybean, while rotating small grains in the winter and cereal rye as a cover crop. The operation uses a summer cover crop blend of sorghum sudangrass, pearly millet, and sunn hemp. Incorporating a high biomass summer cover crop into this farm's rotation has been very helpful in the suppression of pigweed. Cultivation is used within tobacco, sweetpotato, and soybean to tackle in-season weeds. The farm cultivates using rolling, sweep, and S-tine cultivators depending on the crop and needs of the field. This operation also uses hand-weeding in high value crops (tobacco, sweetpotato) and has also employed flame weeding and currently uses an electric weeder.

Acknowledgment of Previous Contributing Authors

Randy Weisz, Crop Science Extension Specialist, NC State University (retired)

Alan York, Crop Science Extension Specialist, NC State University (retired)

George Place, Former Crop Science Research Associate, NC State University

Molly Hamilton, Former Crop Science Extension Assistant, NC State University

Publication date: March 19, 2024

AG-660

Other Publications in North Carolina Organic Commodities Production Guide

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Organic Crop Production Systems

- Chapter 3: Crop Production Management - Corn

- Chapter 4: Crop Production Management - Wheat and Small Grains

- Chapter 5: Crop Production Management - Organic Soybeans

- Chapter 6: Crop Production Management - Flue-Cured Tobacco

- Chapter 7: Crop Production Management - Peanuts

- Chapter 8: Crop Production Management - Sweetpotatoes

- Chapter 9: Soil Management

- Chapter 10: Weed Management

- Chapter 11: Rolled Cover Crop Mulches for Organic Corn and Soybean Production

- Chapter 12: Organic Certification

- Chapter 13: Marketing Organic Grain Crops and Budgets

- Chapter 14: Organic Market Outlook and Budgets

- Chapter 15: Resources for More Information on Organic Commodity Production

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.