Introduction

Firewood remains a common heating source for households in rural areas of the United States. In 2022, 4 percent of residential energy consumption was derived from wood, and for 2.2 million households, wood was the main heating fuel in 2020 (EIA, 2020). The overall number of households that use wood as a fuel increases with household income. Most households that rely on wood as both a primary and secondary heating source, however, are considered low-income. Therefore, a significant number of households directly depend on a sufficient supply of firewood.

Firewood can be costly to purchase, and especially low-income households can struggle to afford it. Public assistance programs typically do not provide firewood. To alleviate these challenges, firewood banks have been established to provide firewood on a needs basis. They are often associated with a nonprofit organization, such as a church or club. Groups of volunteers cut and distribute the firewood. Logs, and sometimes ready-to-use firewood, are typically donated. In some cases, logs and firewood are purchased to supplement donations to meet the demand.

Maintaining a steady stream of wood donations can be challenging and failure to do so can negatively impact the longevity of a firewood bank.

The goal of this study was to assess whether firewood banks could produce and sell other primary products, such as slabs and lumber, as a way to generate additional income, thereby improving their financial standing. Some primary products are relatively simple to make and require only minimal initial investment. The urban wood movement has demonstrated the possibility of creating economic impact through small portable sawmills. But this idea comes with its own set of challenges, because the safe and efficient operation and maintenance of a portable sawmill require trained personnel and operational funding.

Not all logs that make good firewood are worth cutting into lumber. But it can be assumed that among the many donated logs, some would be worth the effort to make a higher-value product. Softwoods, sometimes rejected as firewood due to their high creosote content, would make a suitable resource for lumber. Depending on the species and the origin, large-diameter hardwood logs could be cut into slabs, and some of the smaller ones into lumber.

To gather basic information about the operations and challenges of firewood banks, and their ability to add other primary products, North Carolina State University's Wood Products Extension team sent out a survey to wood banks across the United States. The 30-question survey covered a range of topics related to wood bank operations to gain a better understanding of the successes and challenges that impact the longevity and effectiveness of these organizations.

The survey was sent to 101 firewood banks in the United States. Responses were received from 19 firewood banks in 11 states. The average age of participating firewood banks was 10 years, with the oldest being 41 years old and the youngest being one year old.

Firewood Bank Fundamentals

Diversifying their products beyond firewood could create an additional revenue stream and help sustain and grow the overall impact of firewood banks. The expansion of firewood banks is typically constrained by limited access to labor, high-quality logs, equipment and technology, space, and skill sets.

Labor

Firewood banks operate with the help of volunteers who are motivated and engaged by the overarching mission to support the community and assist those in need. On average, survey participants were supported by 35 regular volunteers and 130 seasonal volunteers, with a maximum of 300 regular volunteers and 500 seasonal volunteers. These volunteers typically include members of churches, semiretired individuals, and retirees. For many, the firewood bank provides an opportunity for social engagement within the community.

In one example, a partnership with a college creates a consistent source of volunteers. It is a graduation requirement for students to engage in community service and the on-campus firewood bank benefits from their involvement. In many cases, the average age of volunteers is relatively high, with semiretired and fully retired individuals composing the majority of volunteers. Retirees are often seeking opportunities to apply their skills, stay physically active, and find fulfillment.

Skills

The range of skills available depends on the leadership and the volunteers. Retired individuals can contribute skills gained from their previous careers. Safety in the operation of splitters and chainsaws is a top priority; often, only selected individuals are allowed to operate chainsaws. Splitting firewood is a highly repetitive and physically demanding task. The size of unsplit wood can be adjusted to reduce the physical requirements.

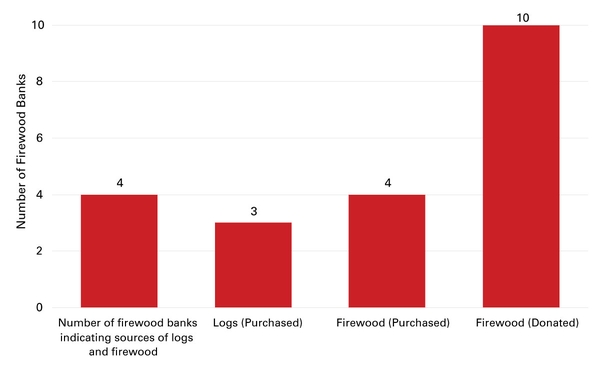

Logs and Firewood

As shown in Figure 1, more than half of the participants receive donated logs. In some cases, firewood is also donated or externally purchased. Partnerships with tree companies, municipalities, and private landowners help ensure a steady supply.

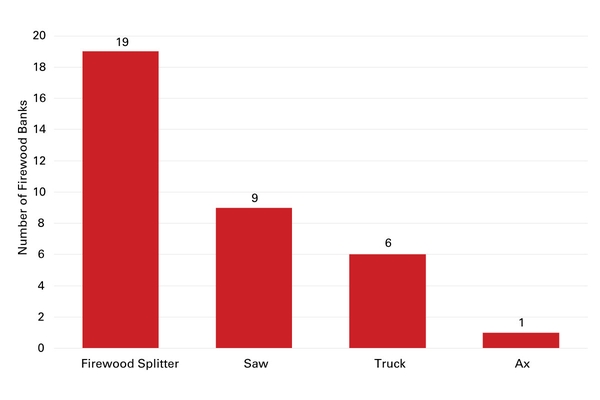

Equipment and Technology

The capacity of a firewood bank is determined by the number of firewood splitters. Splitters are relatively inexpensive, easy to operate, and commonly used in the production of firewood. As shown in Figure 2, all participants consider firewood splitters their most important equipment. Unlike firewood processors, splitters cannot cut logs to length; therefore, chainsaws are ranked as the second most important piece of equipment.

Approximately one-third of the participants prioritize trucks for transportation. But these are of lower priority because volunteers often use their own trucks to deliver firewood, with the firewood bank reimbursing them for their gas expenses.

During personal discussions with firewood bank operators, it became clear that moisture meters were used only occasionally, if at all. Determining and tracking the moisture content of the wood did not play a role. Operators stated that lower-quality firewood is better than no firewood for many of the recipients. The firewood is typically left in piles to air-dry until it is picked up or delivered. While some survey participants used crates or pallets to store the wood, the majority left it uncovered in a pile.

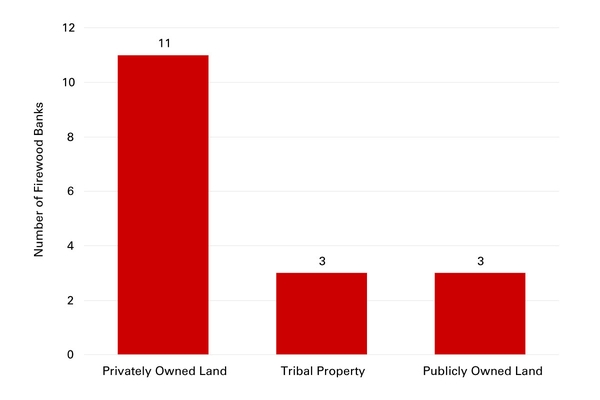

Space

Most firewood bank land is privately owned (Figure 3). Some firewood banks sit on tribal land, and some on publicly owned land. Space in general does not seem a major concern, mostly because the storage of large amounts of firewood was not observed. Inventory moves quickly, limiting the amount of needed space.

Recipients

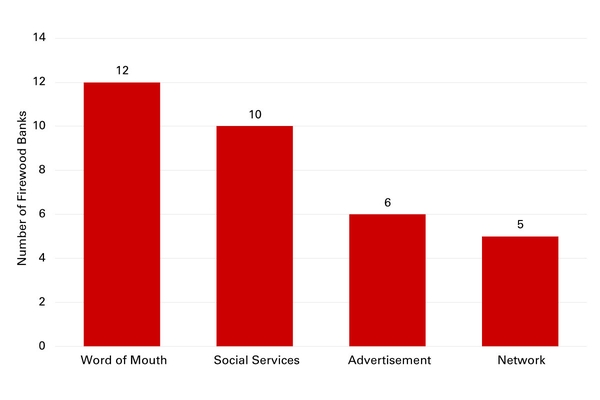

The average number of households served among participating firewood banks was 140. The average annual distribution by the 19 responding banks was 382 cords of firewood. The largest firewood bank delivered 3,000 cords, while the smallest distributed 4 cords. The number of households served ranged from 10 to 400.

Firewood banks employ various methods to identify potential recipients. As illustrated in Figure 4, word of mouth is the most commonly used method, followed by social services. The collaboration with social services and the local municipality appears to be highly efficient in identifying households in need. Six of the participants actively advertise their services, with some using social media. Local networks were mentioned by five participants. Sixteen participants indicated that they use a combination of these methods.

Analysis

Is the Addition of Other Primary Products Feasible for Generation of Additional Income to Help Ensure Firewood Bank Longevity?

The process employed by firewood banks to produce firewood is the simplest way to transform a log into a low-cost mass-produced product. As mentioned earlier, resources are often donated, and the equipment and production steps are nonautomated and minimal.

Cutting slabs and lumber using a portable sawmill is also not automated, but it requires advanced skills and experience. On a volunteer basis, meeting these requirements for the successful operation of a portable sawmill might be challenging, as the skill level required exceeds typical volunteer abilities.

Logs must meet specific quality standards to be suitable for sawing into marketable products. Factors such as species and dimensions significantly impact the end value of the product. Because logs are donated, their suitability for lumber and slab production remains uncertain. Logs from certain locations, such as the edges of pastures and fields, may contain more metal, increasing the risk of injuries and premature sawblade failure and raising costs. Optimizing the yield and quality of the end product also requires a good understanding of log anatomy.

While a portable sawmill can operate on a relatively small footprint, space would be needed for air-drying the cut lumber and slabs on sticks for several months. The wood should be protected from the elements, covered on top, and shielded on the sides with shade cloth. The site should be free of vegetation, and the ground must support both the wood and the equipment for handling it. The operation might also need space for a dry kiln, and for sales.

Slabs for sale are typically displayed leaning against a wall, similar to art in a gallery, to showcase the wood's beauty and highlight its unique anatomical features. Customers who purchase slabs or lumber often have high expectations, especially if the products are sold at market prices. There is direct competition in terms of quality with other for-profit businesses. It can be assumed, however, that some clients will accept lower quality because they value the overall mission of the firewood bank.

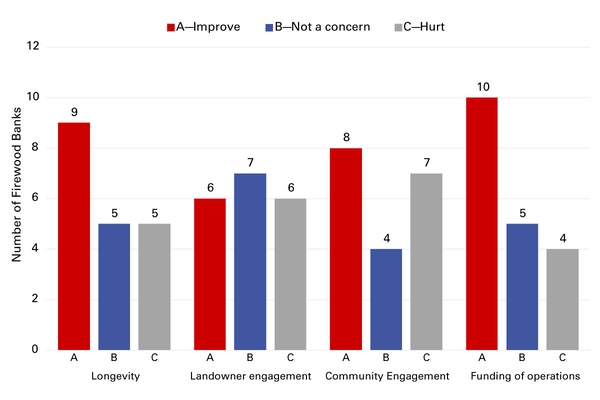

When asked about the potential impact of forming partnerships to produce wood products, participants generally predicted that funding and longevity of the firewood bank would be positively affected. But the results in Figure 5 indicate that community engagement may suffer. Volunteers are typically motivated by the good cause of the operation, and introducing a commercial, for-profit element could potentially negatively impact volunteer engagement. Landowner engagement was expected to improve and decline equally, with concerns about potential decreases in log donations.

This research into the characteristics of firewood banks and their capacity to add sales of wood slabs and lumber to increase their financial stability and longevity leads us to conclude that this funding model as previously described is unlikely to be successful and sustainable.

Conclusion: Community-based Wood Processing Centers as an Alternative

An alternative concept to realize these partnerships is the community-based wood processing center. Participants and components would be loggers, a sawmill (may be portable), dry kilns, a mulch grinder, a woodshop, and a firewood processor.

The central point of the operation is the log yard, where loggers, tree companies, and small tract owners bring logs for sale. They are then sorted based on their best uses for the sawmill or the firewood processor. The mulch grinder grinds up waste and materials from the community. Lumber from the sawmill is dried and then delivered to the wood shop, where it is turned into value-added products, such as flooring, furniture, garden and planter boxes, and construction material. All other logs are made into firewood. The waste from the sawmill is used by the mulch grinder and the firewood processor. The goal is to optimize the use of the wood and create a small economic impact that benefits the community.

The individual companies that make up the community-based wood processing center share rent, utilities, and equipment. Retail sales are made from the center and serve the public with various wood products. Because all the resources are local, all the income stays within the community.

Some of the firewood is sold at market prices, and some is given away for free to people in need.

The main factor in the success of such centers is the partnership between multiple companies, each holding a share of the operation, similar to a co-op. A local church or nonprofit currently running a firewood bank could participate in this partnership. In this case, the skills and expertise needed to produce and sell products other than firewood are in the hands of experienced partners.

References

U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), Office of Energy Demand and Integrated Statistics, Form EIA-457A of the 2020 Residential Energy Consumption Survey. ↲

By Frederik Laleicke, assistant professor and Wood Products Extension specialist, Department of Forest Biomaterials, and Allie Saffioti, undergraduate student in Sustainable Materials and Technology, Department of Forest Biomaterials.

Publication date: Jan. 30, 2024

AG-958

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.