Introduction

Soybean aphid, Aphis glycines (Matsumura), Aphididae, Hemiptera

In September 2005 colonies of soybean aphid, Aphis glycines, were found in North Carolina soybeans. A crop consultant had first found the pest on beans in a Chesapeake, Virginia field in early September and this field was subsequently treated. Later in September, fields with low levels of the aphid were detected in three North Carolina counties — Gates, Currituck, and Camden. These populations never reached the treatment threshold. However, in 2005 many Virginia fields were treated for this pest, particularly in the Northern Neck and Eastern Shore regions. These observations represent the first verified report of soybean aphid in North Carolina. However, in the following years, we can easily find this insect in many soybean fields, but almost always at sub-threshold levels. They are most noticible in cool-cloudy summers.

Distribution of Soybean Aphid

Soybean aphid was first discovered in the United States, in Minnesota, in 2000. During that same year it was also found in Wisconsin, Michigan, Indiana, and Iowa. Since that time it has spread very rapidly and is now found in all major soybean growing states, as far south as Mississippi and Georgia. The soybean aphid is widely distributed in eastern Asia (China, Japan, and Southeast Asia to Malaysia and Indonesia) and has also been introduced into Australia. This wide distribution, from temperate to tropical environments, indicates that soybean aphid can adapt to most regions of the United States. However, the soybean aphid introduced into the United States appears to have come from northern latitudes since it uses an alternate host on which to over-winter as eggs — a behavior common to cold adapted aphids.

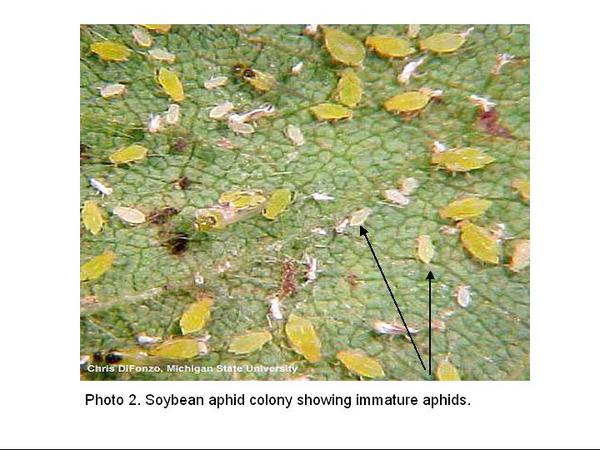

Identification

The soybean aphid is a close relative of the cotton aphid, which is commonly found in North Carolina, and is familiar to many farmers. Soybean aphid is the only aphid found in the U.S. that will develop large colonies on soybean plants. Adult soybean aphids are generally yellow, have black cornicles (cornicles are tail-pipe looking structures at the back of the body), and are approximately 1⁄16 of an inch long when fully grown. Young aphids look like adults without wings but are smaller. Adult aphids may be wingless or, during periods when they migrate, develop wings.

Soybean Aphid Biology

In the spring, eggs hatch into female winged soybean aphids. These adults can move on wind currents and do not need to mate. They move to soybean fields and begin laying living young, not eggs. New aphids may reach reproductive maturity in 3-7 days (depending on temperature) and may double their population every 5 days under favorable conditions. Populations can expand rapidly. Aphids may infest vegetative stage soybeans and remain in the crop into the late reproductive period. Later in the season both males and winged adults appear in the population, in response to plant chemical and photoperiod changes, develop wings, and move from the fields. These adults mate and lay eggs to pass the winter. Eggs are laid on several species of buckthorn bushes. Southern adapted populations in Asia may be active all year.

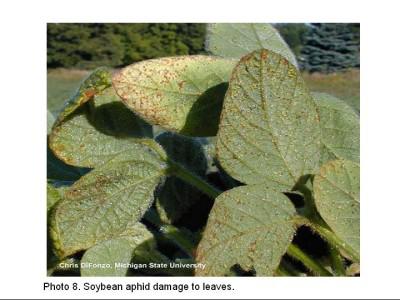

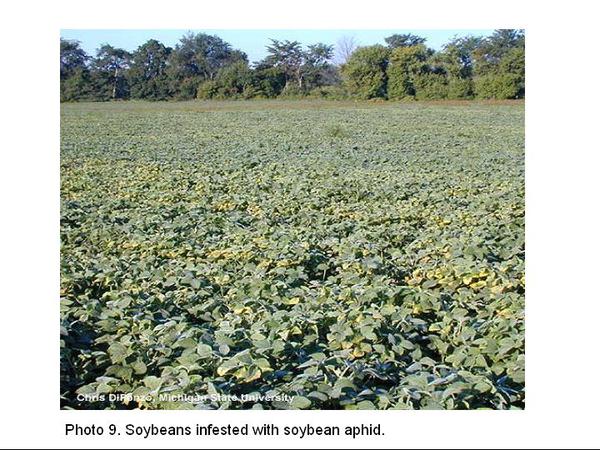

Damage

Soybean aphids suck sap (phloem) from soybean plants and cause plant stress. Excess sugars in the plant sap, not needed by the aphid, are excreted by the aphid as a liquid called “honeydew”. Honeydew sticks to plant foliage providing food for fungi to grow upon; these black colored fungi can discolor the plants. In vegetative stage plants, aphids are only a threat under very high populations. “R” stage soybeans are more sensitive to aphid damage, particularly in early reproductive stages (e.g. R1 – R3). Very high numbers of soybean aphid are capable of causing significant growth reduction, distorted foliage, and lower seed yields. A study by Wang et al. (1996) found that soybean yields were reduced by 27.8% and plant height decreased by ca. 8 inches in seriously infested plants. Insecticide tests have shown yield increases from 10% to 20% depending on aphid population density, product used, and other plant stresses.

Virus Transmission

The soybean aphid is a known vector of a number of plant virus diseases. For example, some domestic viruses spread by soybean aphid include alfalfa mosaic virus, soybean mosaic virus, and bean yellow mosaic virus.

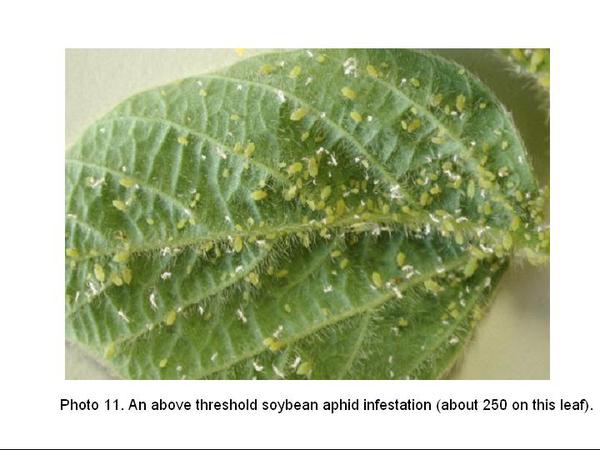

Scouting and Thresholds

In the Midwest, scouting is achieved by examining plants for signs of aphids (e.g. disfigured leaves, ants on plants, cast aphid skins, honeydew on leaves) and aphids in plant terminals. Scouting begins in mid-vegetative stages and continues to R5 (seeds forming in pods); it is done weekly. Aphids are estimated on the leaves and an average of five samplings is compared to a threshold of 250 aphids per plant.

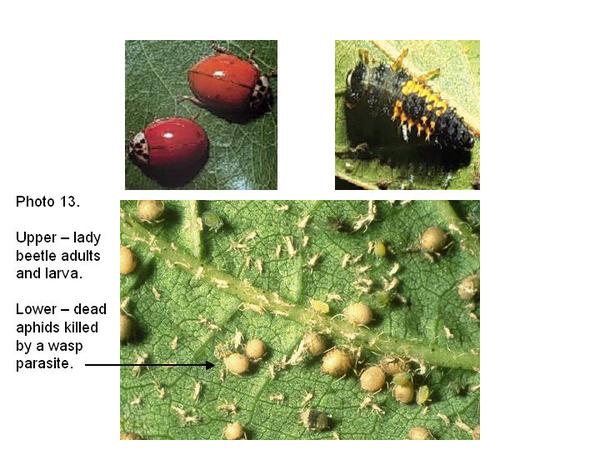

Biological Control

Extension entomologists recommend the use of naturally occurring biological control agents for cotton aphid management in North Carolina. It is likely that this same approach will reduce populations of soybean aphid. Parasitic wasps, insect predators (especially certain bugs and beetles), and a parasitic fungal pathogen of aphids can exert a powerful influence to keep aphids in check. Basically, all the farmer has to do is to avoid disrupting the field by spraying insecticides at the wrong time, and thereby letting the biocontrol agents build-up. Most spraying for corn earworm and other insects in North Carolina occurs after plants pass aphid sensitive stages and will likely not conflict with aphid management. However, early spraying may lead to higher aphid numbers.

Will Soybean Aphid Become an Important Pest in North Carolina Soybeans?

Currently, soybean aphid has a northern-adapted over-wintering behavior that relies upon an alternate over-wintering host (a couple of species of buckthorn). In North Carolina, the soybean aphid has trouble surviving winter in substantial numbers due to the relative low number of buckthorn bushes. This means that aphids will have to travel into North Carolina, on air currents, to infest vegetative stage soybeans in order to have damaging populations at early reproductive stages. This will be unlikely, except, in situations where fields are disrupted by early insect sprays. However, insect pests that expand their range often genetically adapt to new environmental conditions. In Asia the soybean aphid inhabits lower temperate and sub-tropical latitudes that do not require egg laying for over-wintering, indicating that our northern adapted soybean aphid probably can achieve a strain that does not need buckhorn to over-winter. However, soybean aphid rarely reaches economically damaging levels in North Carolina.

Acknowledgment

Information and pictures for this website was gathered from the following sources:

Soybean Aphid in Iowa – 2005. by M. E. Rice and P. Pedersen, Iowa State University

Soybean Aphid in Nebraska. by Tom Hunt, University of Nebraska.

Soybean Aphid. Plant Health Initiative, NCSRP.

Minnesota Soybean Production, Soybean Aphid. by Ken Ostlie, University of Minnesota.

Soybean Aphid. Center for Regulatory and Environmental Information Systems.

Dow AgroSciences CD, “Soybean Aphid.”

Publication date: March 17, 2020

Reviewed/Revised: Dec. 18, 2024

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.