Introduction

Wetlands are an important natural resource and are protected at the state and federal levels. Wetland regulations are often controversial and confusing to homeowners, landowners, and developers. This publication provides an overview of the historical wetland trends in North Carolina, reviews the evolution and current status of wetland regulations (as of November 2021), and summarizes the potential new impacts of climate change on wetlands in the state.

Trends in Wetland Conversion and Loss

Importance of Wetlands

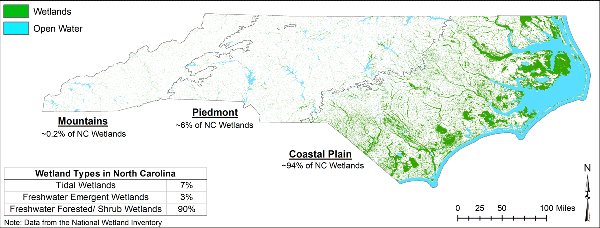

North Carolina hosts a variety of wetland types, with vast riverine and estuarine wetland areas concentrated primarily in the coastal plain. Other wetland types are found across the state from the mountains to the coast (Figure 1). Recent estimates indicate there are approximately 4 million acres of wetlands remaining in North Carolina, covering about 12% of the state (Fish and Wildlife Service, 2020). These wetlands provide many valuable ecosystem services to society, including water quality improvement, flood mitigation, timber production, wildlife habitat, carbon sequestration, coastal protection, and recreation (Mitsch & Gosselink, 2007; Walbridge, 1993), as well as some less-recognized benefits, such as cultural, aesthetic, and educational values (Mitsch et al., 2015). In addition, wetlands provide critical habitat in North Carolina: about 70% of the rare and endangered plant and animal species in the state are dependent on wetlands (Fretwell et al., 1996). However, only recently has society started to fully recognize the array of benefits wetlands provide. One recent study of coastal storms from 1996 to 2005 found that, on average, one square kilometer of wetlands saves $1.8 million in property damage (Sun & Carson, 2020). For more information on the functions and value of wetlands in North Carolina, how to identify wetlands on the landscape, and where to find wetlands near you, reference the NC State Extension publication Natural and Constructed Wetlands in North Carolina: An Overview for Citizens, AG-856, and NCWetlands.org.

Wetland Losses

Over one-half of the wetland area in the United States has disappeared since European settlement (Dahl, 1990). Losses were extensive in the southeastern U.S. (Hefner, 1994), for coastal watersheds in particular (Dahl & Stedman, 2013). From the 1950s to the 1980s, hundreds of thousands of acres of wetlands were lost each year (Table 1), 85 to 90 percent of which occurred in southeastern states. Nationwide, wetland losses have slowed considerably since the late 1980s as a result of federal initiatives, and there was even a modest gain of net wetland area between 1998 and 2009 (Dahl, 2005; 2011)

Table 1. Changes in Wetland Area in the United States (lower 48). Estimates are taken from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

|

Period

|

Change in Wetland Area (acres/year) |

|---|---|

|

1950s – 1970s |

-458,000 |

|

mid-1970s – mid-1980s |

-290,000 |

|

1986 – 1997 |

-58,500 |

|

1998 – 2004 |

+32,000 |

|

2005 – 2009 |

-12,500* |

*not a statistically significant change

Wetland losses in North Carolina have largely reflected those occurring at the national level. Losses were particularly severe from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, a decade in which 1.2 million acres of wetlands disappeared (Hefner, 1994). Since that time, losses have slowed substantially in North Carolina; however, coastal plain wetlands (accounting for 95% of NC wetlands) still declined by about two percent (~62,500 acres) between 1994 and 2001 (Carle, 2011). Little information exists on wetland trends in North Carolina since 2001; however, analysis of the National Land Cover Dataset (NLCD) indicates that an estimated 22,000 acres of wetlands were lost between 2001 and 2016, mostly in the coastal plain. While there is uncertainty associated with the NLCD data, they show wetland losses have slowed significantly compared with previous decades.

Drivers of Wetland Loss

Causes of wetland loss in the southeast U.S. vary but have been driven mostly by intensive drainage for agricultural use and forestry, as clearing and drainage were largely encouraged and incentivized by federal government policies during the 19th and most of the 20th centuries (Mitsch & Gosselink, 2007). In the late 1800s, as mechanized ditching technology accelerated that which was limited by hand labor, North Carolina formed drainage districts to coordinate localized drainage for agricultural and road development. The 1909 North Carolina Drainage Act approved bonds for farmers to pay for drainage work, and by 1920 some 81 drainage districts were organized in the state (O’Driscoll, 2012). Some of the largest losses of wetlands to agriculture occurred in the period after World War II through the mid-1980s (Ainslie, 2002). In the 1940s and ‘50s, federal flood control statutes subsidized more drainage and flood control projects (O’Driscoll, 2012). One example of this is the Watershed Protection and Flood Prevention Act of 1954 (PL-566) that funded extensive drainage and stream channelization projects in the name of flood control that resulted in the drainage and filling of wetlands. More recently, losses of wetlands can be attributed to the logging of forested wetlands, urbanization, and other development (Dahl, 2011). For example, from 1998 to 2004, development accounted for 61% of the freshwater wetland losses in the U.S.

The relatively modest loss in net area over the last two decades has masked what appears to be more concerning losses in wetland function. Although many different wetland types are impacted by development, wetland losses have been concentrated mostly in forested wetlands, which are some of the most difficult wetland types to restore. Consequently, much of the restoration and creation of wetlands has resulted in freshwater marshes and ponds (Dahl, 2011). This “out-of-kind” replacement with wetland types that are easier to create results in wetlands that do not function in the same manner as the lost wetland ecosystems. Even when similar wetland types are restored, research indicates these projects can take decades to develop into high-functioning wetland ecosystems (e.g., Moreno-Mateos et al., 2012; National Research Council, 2001).

In addition, hundreds of thousands of wetland acres have been reclassified as other wetland types (e.g., forested wetland to shrub or herbaceous wetland due to logging) because of disturbance and alteration (Dahl, 2005, 2011). While this conversion to other wetland types does not result in a net loss of overall wetland area, it can still result in altered ecosystem function (Whigham, 1999) and loss of important habitat.

Overall, while wetland losses have slowed considerably, wetland function continues to decline, and will remain an issue as populations continue to grow and development competes with wetlands for land area. Population growth will stress water resources and pose the risk of wetland water sources being diverted to other needs (Burkett & Kusler, 2000). In already-stressed coastal watersheds, where population growth has nearly tripled the national rate over the last four decades (NOAA, 2013), the impacts could be the most severe.

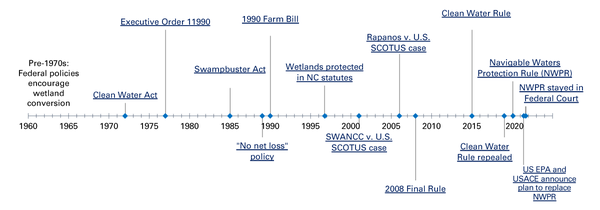

Evolution of Federal Wetlands Policy

Protection of North Carolina’s critical wetland acreage and the numerous ecosystem services that wetlands of all types provide requires a mix of federal and state policies, statutes and regulations. Though much progress has been made in the last half-century in authorizing and implementing programs to stem wetland loss, much debate and confusion continues on the extent of government jurisdiction over rights to alter wetland features on one’s private property, as well as a government’s power do so for a public purpose. While wetland losses have slowed considerably, wetlands are still vulnerable to development and pollution. Recently, federal regulations stepped back federal wetland protections, at least temporarily (NWPR, 2020). In addition, climate change is emerging as a serious threat to many wetland ecosystems in North Carolina through changes in temperature and precipitation patterns (Kurki-Fox et al., 2019); an ironic twist since critical wetland functions such as carbon sequestration, flood control, and storm surge offer protection against climate change.

Even as federal law and policy has shifted from wetland drainage towards wetland protection, the limits of such protections remain hotly debated. Currently, there is no single federal law devoted to wetland protection (Mitsch & Gosselink, 2007). Instead, components of different statutes require or authorize several agencies—including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) —to address wetland degradation. Agencies differ in their interpretations of their jurisdictional mandates, often contributing to legal conflicts over the extent of wetland protections (Copeland, 2013). Regardless, wetland protections have come a long way in the last few decades, and protection is stated as federal policy.

The primary federal wetland protection statute is the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1972 (a.k.a. the Clean Water Act [CWA], 33 U.S.C. §1251 et seq.). Section 404 of CWA protects wetlands under a general requirement that any person who intends to place, dredge, or fill material into “Waters of the United States” (colloquially called “WOTUS”) first obtain a permit from the USACE (Mitsch & Gosselink, 2007). WOTUS refers to waters that are used for interstate commerce or are adjacent to these waters and their tributaries, and as such are the limits of federal regulatory jurisdiction (EPA, 2018). This definition applies to many types of wetlands connected to such waters. For many people, it is counterintuitive that wetlands would be protected as waters of the U.S. because most are not “navigable”; however, it is the connectivity to navigable waters and their ability to protect the quality of nearby surface waters that allows for their protection under Section 404 of the CWA. Wetlands, therefore, are protected from filling and dredging under this federal law.

Five years following the creation of Section 404 of the CWA, President Jimmy Carter signed an executive order in 1977 requiring all federal agencies to include wetland protection measures in projects under their management. The order required agencies to "take action to minimize the destruction, loss, or degradation of wetlands and enhance the natural and beneficial values of wetlands" (Executive Order 11990).

Though the CWA was a landmark law for reducing wetland loss from most residential and commercial development, the CWA nonetheless allowed—as an exemption—conversion of wetlands for agricultural and silvicultural development. Congress closed this loophole with enactment of the “Swampbuster” provision of the Food Securities Act of 1985 (a.k.a. the “1985 Farm Bill”). This provision linked wetland conversion in agriculture to qualification for federal farm subsidy and other programs. Farmers who drained, filled, or otherwise altered wetlands for agricultural use from that point forward became ineligible for federal farm program benefits (Copeland, 2013).

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, more and more research demonstrated the important ecosystem services that wetlands provide to society. In 1989, the EPA, in conjunction with other federal agencies, established a stronger policy of “No Net Loss” of the nation’s wetlands. The goal of achieving “No Net Loss” was primarily facilitated through conservation and restoration programs such as the Conservation Reserve Program and the Wetland Reserve Program (authorized by the 1985 and 1990 Farm Bills, respectively) as well as the enforcement of the CWA and “Swampbuster” provision (Copeland, 2013). It should be noted that such programs have evolved with each Farm Bill, with current wetland protection a component of the 2018 Farm Bill’s conservation easement program.

Even with federal policy on wetlands protection unequivocally stated, the implementation of the jurisdictional extent of that federal policy (i.e., whether a particular wetland feature is protected by federal regulation) has been the subject of public debate, contradictory rulemaking, and litigation. While the majority of wetlands acreage are considered WOTUS and subject to Section 404 without question because they share water with (and are thus connected to) navigable waters, federal protection (under the CWA) of wetland types in other landscape positions, such as pocosins, bogs, and Carolina “bays” (upland oval depressions unique to North and South Carolina), are often questioned.

The U.S. Supreme Court has considered the question of when wetlands are protected under the CWA and thus considered “jurisdictional” on several occasions. As noted previously, the term “Waters of the United States” (“WOTUS”) denotes the jurisdictional limit of federal regulation over water quality (i.e., when federal law may limit land use impacting wetland features). The question of “When is a wetland considered WOTUS?” evolved through several U.S. Supreme Court decisions reviewing EPA’s and USACE’s administrative interpretation of the CWA’s application to wetlands, and thus the requirement of a Section 404 permit when filling or dredging. This line of cases culminated in 2006 with Rapanos v. United States, 547 U.S. 715 (2006), where the U.S. brought suit against the developers and landowners who filled wetlands in Michigan without a permit, in violation of the CWA. Though Rapanos produced a 5-4 decision on what should be done next with the matters involved, the five majority justices were unable to reach a majority rule due to conflicts in the interpretation of how a wetland must be connected to a navigable waterway. This result in Rapanos is called a “plurality opinion.” Thus, Rapanos produced two legally valid, but conflicting, rules for determining whether a wetland is considered WOTUS. One rule of Rapanos, held by four justices led by Justice Antonin Scalia, required that a wetland can be considered WOTUS “only if it abuts a tributary with a continuous surface connection to a traditionally navigable waterway” (also referred to legally as “navigable-in-fact”). The other rule, argued by Justice Anthony Kennedy, rejected Justice Scalia’s “surface connection rule” as an overly simplistic interpretation, proposing that a wetland’s hydrologic nexus to a navigable waterway should rely on more factors than just a simple surface connection. One example raised by Justice Kennedy concerned whether several wetlands working together in an upland landscape position to slow water drainage and soil loss can “affect the physical, biological, and chemical integrity of the downstream navigable water.” According to precedent from a prior U.S. Supreme Court case on application of rules produced in plurality opinions, Justice Kennedy’s narrower “significant nexus” rule became—for a time, at least—federal policy.

In response to Justice Kennedy’s hydrologic nexus rule in Rapanos, the US EPA proceeded with rulemaking to expand CWA jurisdiction in 2015 with the Clean Water Rule (CWR). The CWR as written would have allowed US EPA and USACE to apply case-by-case federal protection to wetlands lacking a direct surface water connection to navigable waters (i.e., wetlands that do not abut a tributary leading to traditional federal waters) but whose hydrologic connection could be scientifically linked to traditional federal waters. Though the 2015 CWR was finalized and went into legal effect, landowners and various advocacy groups successfully challenged the 2015 regulation in federal courts across the country, which effectively halted the rule’s implementation.

The CWR was repealed by the US EPA under the next presidential administration and was replaced by the Navigable Waters Protection Rule (NWPR) in 2020. The NWPR put into effect the broader “abutment to continuous surface connection” rule created by Justice Scalia in Rapanos. The most immediate impact of the NWPR was that wetlands that do not abut a tributary with continuous surface connection to traditional federal surface waters fall outside the protections of the Clean Water Act. Like its predecessor rule, the NWPR spawned litigation to stay the rule, also hampering its implementation before another change in presidential administrations.

The NWPR achieved a more limited federal jurisdiction over wetlands by both implementing the direct hydrologic surface connection rule, and then further defining what may be considered a “tributary” providing such hydrologic surface connection. (A common understanding of a tributary may be considered any land feature that drains upland and conveys water toward a larger water body.) Under this rule, the first question became “Does this wetland abut a tributary of a traditionally navigable waterway?” Under NWPR, abut meant the wetland and the tributary directly share water, uninterrupted by earth. For example, the wetland and tributary are not separated by a dike or other feature lacking a pipe or culvert providing a direct hydrologic surface connection. If the wetland abuts such a conveyance, the next question was then “Is this legally a tributary?” A drainage channel, swale, culvert, gulch, etc., may be considered a tributary but only if such drainage feature has continuous or intermittent flow, which is a seasonably predictable flow in a “normal year” (NWPR, 2020). Drainage features considered ephemeral—which drain water only in direct response to rainfall—were not considered tributaries under this rule. Drainage ditches were not considered tributaries, unless they served as waterways used in navigation by watercraft (including small and non-motorized watercraft) or were created from the course of a tributary (e.g., as a deepening of an existing tributary course).

The NWPR went into effect on June 23, 2020. The rule was challenged by various private agricultural and environmental groups (some of the former felt the rule still extends federal jurisdiction too far), and additional lawsuits were filed by states. One suit joined by North Carolina in May 2020 (NCDOJ, 2020) argued that the rule ignored scientific evidence that wetlands excluded in the NWPR contribute to the integrity of our nation’s waters and lacked reasoned explanation or rational basis for overturning the long-standing policy that relied on Justice Kennedy’s “significant nexus” standard to define WOTUS. Estimates provided by the EPA suggested that 50 percent of the wetlands would lose CWA protections if the NWPR remained in effect (Wittenberg, 2018).

In June 2021, the EPA and USACE announced their intent to replace the NWPR with rules that would restore protections in place prior to the 2015 WOTUS rule and create a lasting definition of WOTUS (US EPA, 2021). Therefore, additional changes to federal wetland regulations are again on the horizon. Table 2 and Figure 2 summarize the complex history of federal wetland legislation and regulations in the U.S. to date.

Table 2. Milestones of federal wetland legislation and regulations.

|

Year |

Milestone |

Action |

|---|---|---|

|

pre-1970s |

Federal policies only encouraged wetland conversion. |

|

|

1972 |

Clean Water Act |

Originally known as the Federal Pollution Control Act, the CWA regulates the discharge of pollutants into the nation’s surface waters, and established the process of compensatory mitigation. The CWA was amended in 1977 and 1987. |

|

1977 |

Executive Order 11990 |

Required all federal agencies “take action to minimize the destruction, loss, or degradation of wetlands.” |

|

1985 |

Swampbuster Act |

The “Swampbuster” provision of the Food Securities Act of 1985 deemed farmers ineligible to receive USDA subsidies if they alter wetlands for agricultural use. |

|

1989 |

"No Net Loss" Policy |

The “No Net Loss” policy established a federal goal of zero net loss of the nation’s wetland resources. |

|

1990 |

Farm Bill |

The 1990 Farm Bill established the Wetland Reserve Program, encouraging wetland restoration on agricultural lands. |

|

1996 |

NCAC 02B .0231 |

NCAC 02B .0231 established standards for wetland classification and standards. |

|

2001 |

SWANCC v. USACE |

Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County (SWANCC) v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers – The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Migratory Bird Act of 1918 cannot be used to establish CWA protection status for wetlands. |

|

2006 |

Rapanos v. United States |

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that wetlands must have a “significant nexus” to navigable waters in order for CWA protections to apply. |

|

2008 |

Final Rule of the CWA |

The Compensatory Mitigation for Losses of Aquatic Resources Final Rule expanded CWA guidelines to raise standards for compensatory mitigation. |

|

2015 |

Clean Water Rule |

The Clean Water Rule expanded CWA protections to isolated wetlands. |

|

2019 |

Clean Water Rule repealed. |

|

|

2020 |

Navigable Waters Protection Rule |

The Navigable Waters Protection Rule (NWPR) established that wetlands that do not abut a tributary with continuous surface connection to traditional federal surface waters fall outside the protections of the CWA. |

|

2021 |

The NWPR is stayed. |

|

North Carolina Wetland Protections

Where federal jurisdiction ends, state law can enact wetlands protection. Such is the case in North Carolina, where, as with federal law, no one statute in is devoted specifically to wetland protection. State wetland protections are found in various statutes, and many wetland protection standards run concurrently with federal requirements, but focus on protection of state waters. North Carolina offers a broad interpretation of “state waters” as “any stream, river, brook, swamp, lake, sound, tidal estuary, bay, creek, reservoir, waterway, or other body or accumulation of water, whether surface or underground, public or private, or natural or artificial, that is contained in, flows through, or borders upon any portion of this State, including any portion of the Atlantic Ocean over which the State has jurisdiction” (NCGS, 143-212(6)). Such definition includes wetlands by regulation (15A NCAC 02B .0202), and wetlands are further defined as riparian – sourced by groundwater or surface water – and non-riparian, those sourced primarily by rainfall (15A NCAC 02R .0102).

Regulations for wetlands in North Carolina start with the state’s Air and Water Resources statute (NCGS, § 143-211) and later the accompanying NCAC 02B water quality standards regulations and anti-degradation policy. The regulations specifically apply to “discharges,” defined as “the deposition of dredged or fill material [e.g., fill, earth, construction debris, soil, etc.]” in 15A NCAC 02H .1301. In addition, the NC Sedimentation Pollution Control Act (NCGS, §113A-50 et seq.) also provides limited protection to wetlands against “land disturbance” development activities that may fall short of the “discharge” definition but otherwise indirectly disturb wetlands with soil runoff. Agriculture and forest management activities can, however, be exempt from such sedimentation control permitting [NCGS, §113A-52.01].

North Carolina’s provides more robust wetlands protection to estuarine and riverine wetlands in the 20 coastal counties subject to the NC Coastal Area Management Act (CAMA) (CAMA, 1974). Under CAMA, any excavation of estuarine waters, tidelands, marshlands, or state-owned lakes in counties designated as Areas of Environmental Concern (AEC) requires a permit from the NC Department of Environmental Quality (NCDEQ) in addition to a federal Section 404 permit (discussed later). These coastal wetlands, defined as “any salt marsh or other marsh subject to regular or occasional flooding by tides, including wind tides” but not “hurricane or tropical storm tides” can typically be identified with one or more of 10 marsh species described in 15A NCAC 07H.0205.

North Carolina implemented rules protecting “isolated wetlands” as early as 1996 (NCAC 02B .0231). “Isolated wetlands” include unique, ecologically diverse ecosystems (see Figure 3a and Figure 3b). Carolina bays and bogs are sometimes not covered by the CWA, and would fall mostly outside the recent NWPR due to their lack of surface–water connection (see discussion above). Even at the state level, wetland protections are always subject to reductions in jurisdiction, and isolated wetlands are particularly vulnerable because they can lack easily defined surface water connections to other regulated waters. For example, as part of a broader regulatory overhaul, the state legislature modified the Isolated Wetland Rule in 2015 to substantially reduce the number of wetlands that require permits (HB 765, 2015). This statute required NCDEQ (then DENR) to revise administrative regulations in order to limit permit requirements to only “basin wetlands and bogs,” (NC WAM, 2010) (basin wetlands are generally defined as depressions surrounded by upland and wetland areas fringing open waters less than 20 acres in size; bogs are found in the Blue Ridge Mountains and northern inner piedmont, formed by seepage and runoff). This eliminated the need to obtain a permit to alter other isolated wetland types, leaving types such as pocosins more vulnerable. This statewide exception “deems permitted” the impacts of disturbance to less than one acre of isolated wetlands in the coastal plain, half an acre in the piedmont, and one third of an acre the mountains (15A NCAC 02H.1305).

Although North Carolina passed a statute in 2011 requiring that no new state environmental regulation may exceed the standards established under federal environmental law, existing regulations (e.g., NCAC 02B .0231) remain in place regardless of any CWA jurisdictional retreat from isolated wetland protection.

Section 404, State Permits, and Mitigation

As previously noted, for wetlands determined subject to federal CWA jurisdiction, a person must generally obtain a federal Section 404 permit before altering any wetland. Applications for USACE Section 404 permits require four main demonstrations by the person wishing to alter a wetland:

- That there is no practical alternative to the project requiring destruction of wetland;

- That no violations of federal law otherwise occur, such as impacting a species listed under the Endangered Species Act or damaging spawning fish habitat under the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (FCMA, 1976);

- That no otherwise significant impact to water quality exists; and

- That the applicant provides some compensatory mitigation to the damage or impact to the wetlands caused by the project.

Compensatory mitigation comprises the creation, restoration, enhancement, or preservation of wetlands to offset any loss of wetland impacted by development projects (National Research Council, 2001). For purposes of Section 404 permitting, mitigation projects that qualify for credits are authorized by NC state statute, with certification oversight by the NC Division of Mitigation services (NCDMS) (NCDEQ, 2020a). In NC, such mitigation can be achieved either by the permittee at the project site or nearby, by purchasing offset credits created by mitigation projects elsewhere in the same watershed (known as Mitigation Banks), or by paying an in-lieu fee within the NCDEQ Division of Mitigation Services (NCDMS) (NCDEQ, 2020).

To streamline the Section 404 application process, the USACE issued general Section 404 permits (valid nationwide) that include a slate of 52 activities deemed to be approved within stated criteria. While these permits are authorized through 2022, the USACE introduced a rule in 2020 to reauthorize these and add five additional activities. For example, Section 404 generally approved activities impacting less than half an acre of non-tidal (or tidal-adjacent) wetlands. These activities include installation of renewable energy facilities, certain stormwater management infrastructure, recreational facilities, mining, and agricultural activities (which extend beyond the normal use exemption) (USACE, 2017). The purpose of the general permit is to streamline the review process, not replace the requirement that a landowner apply for a permit.

In relation to water quality impacts, as a USACE-issued Section 404 permit is a federal action, Section 401 of the CWA requires a water quality certification for the environmental impact of the project. This is delegated to the states and is handled in North Carolina by the NCDEQ Division of Water Resources (NCDEQ 2020b). The requirement for Section 401 certification also applies to other WOTUS-disturbing activities, including damming for ponds, modifying stream and river banks, and building a structure into a waterway. Normal farming and silviculture activities, such as plowing, seeding, cultivating, minor drainage, and harvesting for the production of food, fiber, and forest products, are generally exempt. However, these activities are only exempted when performed by an ongoing operation (recall the 1985 Swampbuster Act); therefore, development activity to establish a farm is not exempt. (The Army Corps of Engineers offers an explanation of Exemptions to Permit Requirements.)

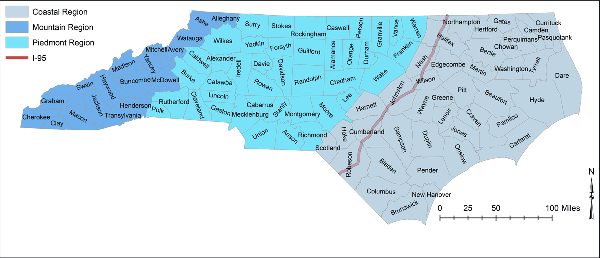

As noted above, North Carolina, by regulation, deems as permitted certain discharge activities impacting isolated wetlands not protected by Section 404. Specifically, for an isolated wetland—again, only basin wetlands and bogs—impacts to one acre of such isolated wetlands in the coastal region (east of I-95) do not require a permit; such permitted disturbance is reduced to half an acre in the piedmont (generally from Franklin County south to Anson County on the east side and Wilkes County to Polk County on the west side) and one third of an acre or less in the mountains (Alleghany County south to Henderson County and westward) (see Figure 4). Such impacts deemed permitted remain subject to sedimentation and other controls to protect downstream surface water quality and remaining undisturbed wetland areas. NCDEQ may issue permits for disturbance of isolated wetland areas greater than the above thresholds, provided such impact has no alternative, water quality impacts are minimal, and mitigation is employed on a 1:1 basis (15a NCAC 02h .1305).

Impacts of Climate Change on Wetlands

In the past, the most significant impacts on wetlands were caused by land use changes (development), which of course have been influenced by changes in federal and state laws. However, major future changes to wetlands may result from another threat - a changing climate. While there are uncertainties regarding the extent of impacts, important wetland functions will be altered by changing precipitation and temperature regimes, and an increase in the frequency of extreme events due to climate change (Burkett & Kusler, 2000). Wetlands are especially at risk because they are located at intermediate landscape positions (i.e., transitional areas between upland and aquatic environments), where even small changes in precipitation and evapotranspiration can have disproportionate impacts on the structure and function of some wetland types. In addition, plant species composition will likely shift as temperatures rise, and extinctions will increase along with the increasing prominence of invasive plant species (Brinson, 2006). Extreme drought, rainfall, flooding (both depth and duration), and storm surge events tend to influence species composition (e.g., Beissel & Shear, 1997; Foti et al., 2012). Thus, wetland plant composition could trend towards a more homogeneous state, facilitated by the elimination of non-tolerant, native species. Researchers have reported climate is already causing local extinctions among plant and animal communities (Wiens, 2016).

In North Carolina, wetlands will be threatened by climate change due to projected higher temperatures, shifting precipitation patterns, and sea-level rise. Increasing salinity and higher water levels in coastal wetlands can lead to ghost forests (Figure 5a) in coastal forested wetlands (Doyle et al., 2007), and sea-level rise may overwhelm some tidal wetlands (EPA, 2016). In peatlands in eastern NC, changes in hydrology due to climate change could substantially lower water levels, which in turn could result in the loss of habitat for some wetland plant and animal species (Kurki-Fox et al., 2019), the breakdown and loss of carbon-rich, organic soils (Erwin, 2009), and an increased risk of peat fires (Figure 5b). The geographically isolated basin wetlands are likely at particular risk (Erwin, 2009). Riverine wetlands could be impacted by the potential changes to streamflow patterns and flooding caused by climate change (Erwin, 2009).

Summary

Wetland loss has slowed considerably as a result of changes in federal laws that were passed in response to the growing recognition of the importance of wetlands to society. However, wetlands are still impacted by development, increased logging, and agriculture. While increased restoration and protections have the potential to buffer some of the impacts on wetlands, restoration projects can require decades to develop and mature to the level of natural wetlands. As a result, the trend over recent decades is a loss of wetland function and biodiversity (Dahl, 2011). Moving forward, climate change and development will further stress wetland ecosystems. If recent changes to wetland protections issued by the EPA remain in place (e.g., NWPR), further wetland losses are likely in the coming years. In June 2021, however, the EPA announced their intent to replace the NWPR; the entire NWPR was stayed in Federal Court in August 2021, and later struck down completely in September. As you can see, wetland laws and regulations are dynamic, so it still remains to be seen what impact future changes will have on the protection of these valuable natural resources.

Information for Landowners

This document summarizes the rules and regulations applicable to wetlands in North Carolina as of November 2021. This information should not be used exclusively to determine if regulations apply to a particular wetland. Landowners should always check with the NC Department of Environmental Quality and US Army Corps of Engineers before proceeding with any projects that impact wetlands on their property (see NCWetlands.org). Violations of Section 404 of the Clean Water Act (including failure to obtain the necessary permits) can result in substantial financial penalties (currently up to $16,000 per day).

Other Resources for Citizens

For more information on the functions and value of wetlands in North Carolina, guidance on how to identify wetlands on the landscape, and where to find wetlands near you, reference Natural and Constructed Wetlands in North Carolina: An Overview for Citizens, AG-856, and NCWetlands.org.

Additional Information

- Wetlands and Water Quality (NC State Extension factsheet AG 473-7)

- NC Wetland Assessment Method (NC WAM) User Manual (PDF, 4.6 MB)

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife: Wetlands Status and Trends

- U.S. Geological Survey: National Water Summary on Wetland Resources

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Wetlands Protection and Restoration (PDF, 288 KB)

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Compensatory Mitigation

- NC DEQ 401 Permitting FAQs

- NC Division of Mitigation Services

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sue Homewood from NC DWR who helped us in our understanding the history of the NC wetlands rules, and also for her insights about the proper interpretation of those rules.

References

Ainslie, W. B. (2002). Forested wetlands. Southern Forest Resource Assessment: Summary Report. Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-53. USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Asheville, NC, 479–499.

Beissel, K., Shear, T. H. (1997). Comparison of vegetational, hydrologic, and edaphic characteristics of riverine forested wetlands on North Carolina coastal plain. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, (1601), 42–48.

Brinson, M. M. (2006). Consequences for wetlands of a changing global environment.

Batzer DP, Sharitz R.R. (2006). Ecology of freshwater and estuarine wetlands.University of California Press, Berkeley.

Burkett, V., Kusler, J. A. (2000). Climate Change: Potential Impacts and Interactions in Wetlands of the United States. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 36(2), 313–320.

CAMA (Coastal Area Management Act of 1974). North Carolina General Statues § 113A-100. (1973, c. 1284, s. 1; 1975, c. 452, s. 5; 1981, c. 932, s. 2.1.)

Carle, M. V. (2011). Estimating wetland losses and gains in coastal North Carolina: 1994–2001. Wetlands, 31(6), 1275–1285.

Copeland, C. (2013). Wetlands: An Overview of Issues (PDF, 365 KB). The Congressional Research Service. Washington, DC.

Dahl, T. E. (1990). Wetlands losses in the United States 1780’s to 1980’s. US Department of the Interior, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Fisheries and Habitat Conservation. Washington, DC.

Dahl, T. E. (2005). Status and trends of wetlands in the conterminous United States 1998 to 2004. US Department of the Interior, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Fisheries and Habitat Conservation. Washington, DC.

Dahl, T. E. (2011). Status and trends of wetlands in the conterminous United States 2004 to 2009. US Department of the Interior, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Fisheries and Habitat Conservation. Washington, DC.

Dahl, T. E., Stedman, S. M. (2013). Status and trends of wetlands in the coastal watersheds of the Conterminous United States 2004 to 2009. US Department of the Interior, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Fisheries and Habitat Conservation. Washington, DC.

Doyle, T. W., O’Neil, C. P., Melder, M. P. V., From, A. S., Palta, M. M. (2007). Tidal Freshwater Swamps of the Southeastern United States: Effects of Land Use, Hurricanes, Sea-Level Rise, and Climate. In W. H. Conner, T. Doyle, & K. W. Krauss (Eds.), Ecology of Tidal Freshwater Forested Wetlands of the Southeastern United States. The Netherlands: Springer.

Erwin, K. L. (2009). Wetlands and global climate change: the role of wetland restoration in a changing world. Wetlands Ecology and Management, 17(1), 71–84.

FCMA (Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act). Public Law 94-265. 90 STAT. 331 (April 13, 1976) (PDF, 5.0 MB).

Fish and Wildlife Service. (2020). National Wetland Inventory. U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Washington, DC.

Foti, R., del Jesus, M., Rinaldo, A., Rodriguez-Iturbe, I. (2012). Hydroperiod regime controls the organization of plant species in wetlands. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(48), 19596–19600.

Fretwell, J. D., Williams, J. S., Redman, P. J. (1996). National water summary on wetland resources. Water Supply Paper 2425. U.S. Geological Survey. Reston, VA.

HB 765 (An Act to Provide Further Regulatory Relief to the Citizens of North Carolina by Providing for Various Administrative Reforms, by Eliminating Certain Unnecessary or Outdated Statutes and Regulations and Modernizing or Simplifying Cumbersome or Outdated Regulations, and by Making Various Other Statutory Changes.), Session Law 2015-286.

Hefner, J. M. (1994). Southeast wetlands: status and trends, mid-1970’s to mid-1980’s. U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Fisheries and Habitat Conservation. Washington, DC.

Kurki-Fox, J. J., Burchell, M. R., & Kamrath, B. J. (2019). The Potential Long-Term Impacts of Climate Change on the Hydrologic Regimes of North Carolina’s Coastal Plain Non-Riverine Wetlands. Transactions of the ASABE, 62(6), 1591-1606.

Mitsch, W. J., Bernal, B., Hernandez, M. E. (2015). Ecosystem services of wetlands. International Journal of Biodiversity Science Ecosystem Services & Management, 11(1, Sp. Iss. SI), 1–4.

Mitsch, W. J., Gosselink, J. G. (2007). Wetlands (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Moreno-Mateos, D., Power, M. E., Comín, F. A., Yockteng, R. (2012). Structural and functional loss in restored wetland ecosystems. PLoS-Biology, 10(1), 45.

National Research Council. (2001). Compensating for wetland losses under the Clean Water Act. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

NCAPA. 2011. The North Carolina Administrative Procedures Act, N.C.G.S. 150B-19.3.

NCDEQ. (2020a). NC DEQ: Stream & Wetland Mitigation Program.

NCDEQ. (2020b). NC DEQ: Stream & Wetland Mitigation Program.

NCDOJ. (2020). Attorney General Josh Stein Files Motion For Summary Judgment in Waters of the United States Case. Press Release. NC Dept. of Justice. Raleigh, NC.

NCWAM. (2010). NC Wetlands Assessment Method User Manual, Version 4.1, October 2020 (PDF, 4.6 MB).

NOAA. (2013). National Coastal Population Report: Population Trends from 1970-2020. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Department of Commerce. Washington, DC.

NWPR (The Navigable Waters Protection Rule: Definition of ‘‘Waters of the United States’’). 78 Fed Reg. 22250. (April 21, 2020) (codified at 33 C.F.R pts. 328 and 40 C.F.R. pts. 110, 112, 116, 117, 120, 122, 230, 232, 300, 302, and 401).

O’Driscoll, M. (2012). The 1909 North Carolina Drainage Act and Agricultural Drainage Effects in Eastern North Carolina, Journal of the North Carolina Academy of Science. Vol. 128, No. 3/4 (Fall/Winter, 2012), pp. 59-73.

Sun, F., & Carson, R. T. (2020). Coastal wetlands reduce property damage during tropical cyclones. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(11), 5719-5725.

USACE. (2017). Summary of the 2017 Nationwide Permits (PDF, 60 KB). Wilmington, NC.

US EPA. (2016). What Climate Change Means for North Carolina. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Washington, DC

US EPA. (2018). About Waters of the United States. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Washington, DC.

US EPA. (2021). Intention to Revise the Definition of "Waters of the United States." U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Washington, DC.

Walbridge, M. R. (1993). Functions and values of forested wetlands in the southern United States. Journal of Forestry, 91(5).

Whigham, D. F. (1999). Ecological issues related to wetland preservation, restoration, creation and assessment. Science of the Total Environment, 240(1), 31–40.

Wiens, J. J. (2016). Climate-Related Local Extinctions Are Already Widespread among Plant and Animal Species. PLos Biology, 14(12), 18.

Wittenberg, A. (2018). EPA claims ‘no data’ on impact of weakening water rule. But the numbers exist. Science Magazine, December 11, 2018.

Publication date: March 14, 2022

AG-913

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.