Soybeans have the most flexible planting date of any row crop grown in North Carolina and are easily adapted to multiple production systems and cultural practices. Due to this flexibility, soybeans can be grown successfully under various crop rotations, cover crops, and tillage practices. Many effective soybean production practices can also maintain or enhance soil health, increasing both economic success and environmental quality. However, what works best on one operation and for one soil may not work for another, so it is important to think about what will most benefit your farming system as a whole.

Soil Health

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) defines soil health as the continued capacity of soil to function as a vital living system that sustains plant, animal, and human life. While there is no single criterion that determines if a given soil is healthy, all healthy soils share some combination of physical, chemical, and biological characteristics that enable ecosystem function, including crop productivity and resilience (for example, the capacity to recover from stress and disturbance). Soils carry out five essential functions: regulating water infiltration and movement; sustaining plant and animal life; cycling and storing nutrients; filtering and degrading pollutants; and providing physical stability and support.

Agricultural practices such as continued high-disturbance tillage, repeated monocropping, and intensive fertilizer and pesticide use can threaten soil health. Over time, these intensive management practices can also elevate disease pressure and diminish soil’s ability to withstand other environmental stressors like extreme heat or flooding. Conversely, maintaining healthy soils can reduce dependence on synthetic chemical inputs, human labor, and farm machinery usage. The USDA-NRCS outlines four guiding principles of soil health management:

-

Minimize soil disturbance

-

Increase biodiversity

-

Maintain living roots

-

Maximize soil cover

Farmers can follow these principles by adopting management practices like crop rotation, cover cropping, and conservation tillage, many of which are already widely practiced by North Carolina soybean producers. Best recommendations to maintain or enhance soil health vary across production systems and North Carolina’s geographic regions. Connect with staff at your local Extension center to prepare a management strategy that supports soil health goals relevant to your farm. By prioritizing soil health, you can support economic productivity and enhance environmental quality.

Soil Microbiomes

Soils are home to diverse, abundant communities of bacteria, fungi, and other microbes not visible to the naked eye. Microbes are most abundant and active at the soil surface (O and A horizons), with fewer microbes at deeper layers. The rhizosphere, or the zone of soil closely associated with plant roots, is a hot spot of microbial diversity and activity. These soil microbial communities, or microbiomes, drive or contribute to the five essential soil functions that support soil health.

Decomposition and Nutrient Cycling: Microbes decompose organic matter, like cover crop residue or insect carcasses, introducing nutrients back into the soil. Microbes transform the essential plant nutrients nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium into chemical forms that plants can readily absorb.

Soil Structure and Water Retention: Many microbes produce biofilms and other “sticky” secretions, which bind soil particles that enhance soil structure and promote water infiltration. Microbial secretions provide the additional benefits of retaining water and improving water-holding capacity.

Plant Growth Promotion and Disease Suppression: Microbes form beneficial relationships with plants that are vital for plant growth and yield. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria in the rhizosphere known as rhizobia form unique symbiotic relationships with soybeans and other legumes. These rhizobia colonize soybean nodules and supply the soybean with nitrogen in exchange for carbon; this relationship is an important example of how beneficial microbes also contribute to soil health. Other microbial communities can enhance soybean tolerance to high salinity, drought, heat, and other environmental stressors.

Adhering to the four principles of soil health management is the best strategy for fostering diverse and beneficial soil microbiomes. For example, maintaining living roots throughout the year with cover crops provides a continuous supply of carbon in the form of root exudates, which are food for microbes. There are commercial microbial products called biostimulants designed to enhance soil health processes or to promote plant growth; while promising, efficacy and field performance can vary widely, particularly across diverse soils and production regions.

Tillage

Tillage management significantly impacts soybean production in North Carolina. Different tillage practices can affect soil structure, water infiltration, soil water retention, nutrient availability, soil organic matter level, nitrogen fixation, and crop yield. There is no single, uniform tillage practice that applies to all fields in North Carolina, due to high soil diversity and climate variability. Based on studies conducted in North Carolina, conservation tillage practices are generally recommended for reducing surface soil erosion and improving soil health. More information about tillage impacts on soybean production can be found at the NC State Extension Soil Health and Management Website.

Conservation Tillage: Conservation tillage, including no-till, reduced-till, or tillage rotation, benefits many soybean producers in North Carolina. These practices help in maintaining soil organic matter, reducing erosion, and improving soil structure and water infiltration. Reduced tillage systems regulate soil temperature and conserve soil moisture during the summer growing season, which is especially important in sandy soils of the coastal plain that are more prone to drought stress due to severe subsurface soil compaction.

Conservation tillage reduces soil disturbance, which promotes formation of stable pores and water infiltration while also improving water-holding capacity. Farmers can reduce disturbance by (1) reducing tillage depth, (2) using narrower points and shanks, (3) reducing speed, (4) using less aggressive tillage equipment, (5) lowering tire pressure, (6) reducing field traffic, (7) reducing equipment weight, (8) using tillage rotation techniques, and (9) minimizing access to waterlogged fields.

For conservation management practices to be successful, factors including soil type, adjacent topography and vegetation cover, distance to major water bodies (or depth of the water table), microclimatic conditions, and at least five years of management history should all inform decisions about tillage equipment and tillage depth. To identify the best tillage practice for your field, contact your Extension agent or a soil management specialist.

Soil Compaction Concerns: Although conservation tillage reduces surface disturbance, it may lead to soil compaction over time, especially in fine-textured surface piedmont soils or subsurface coastal plain soils. Compaction in North Carolina soils is primarily due to field traffic and conducting tillage operations when fields are not dry enough, although tillage disturbance can also contribute to soil compaction. Subsoil compaction can restrict root growth and reduce nitrogen fixation, limiting the soybean plant's ability to access water and nutrients; in this scenario, strip tillage or periodic deep tillage (subsoiling) may be necessary to alleviate compaction. Implementing deep tillage every few years can significantly enhance root growth and yield potential in compacted soils under conventional tillage management. In no-till systems, soils are less likely to become compacted; therefore, deep tillage to alleviate compaction in these systems may be necessary only about once every 10 years. Benefits of no-till farming may also include higher soybean yield, reduced disease pressure, and enhanced nutrient cycling. These benefits are maximized by employing proper residue management and crop rotation.

Cover Crops

The 2022 USDA Census of Agriculture estimated that cover crops were planted on 4.7% of all cropland acres in the United States. North Carolina is well above the national average, with about 9.5% of cropland acres using cover crops.

Short-term benefits of cover crops include weed suppression, soil moisture conservation, disease suppression, nematode suppression, and suppression of some insects. Longer-term benefits of cover crop use can include reduced soil erosion and nutrient leaching. Your desired benefits from using cover crops should guide your species selection and management decisions.

Using cover crops in soybean production may present some challenges, including extra costs, added time for planting and termination, pest transfer (via the “green bridge”), and soil moisture depletion before soybean planting. Several factors, such as biomass accumulation prior to termination, will influence the severity of challenges experienced with cover crops.

Be aware that certain management practices aimed at maximizing a benefit can also introduce some problems. For instance, growers wanting to enhance the weed-suppression ability of their cover crop residue might delay termination; while this practice can lead to increased growth and biomass, it also heightens the risk of pest transfer to soybeans.

Species Selection

Possible categories of cover crops include small grains, legumes, and brassica species. Each of these categories of species can provide distinct advantages. When selecting a species, consider its planting dates, cost, growth traits, and environmental tolerances to ensure it fits in with your location, rotation, and goals. The Cover Crop Selector Tool is an online resource that allows you to compare and select cover crop species.

For several reasons, growing a small-grain cover crop prior to soybeans is a good fit for many producers. Cereal rye remains one of the most popular cover crops to plant before soybeans. Cereal rye’s winter hardiness, later planting date, high biomass production, and long-lasting residue can allow farmers to enhance their weed suppression and soil moisture in the short term, when accompanied by no-till practices.

Soybeans work particularly well with cereal rye because they can fix nitrogen and are not significantly impacted by the nitrogen immobilization associated with small-grain cover crops. Avoiding planting legume and heavy legume cover crop mixes before soybeans is often recommended. Cereal rye and other small-grain cover crops can add diversity and often will not host some pests and diseases, for example, soybean cyst nematodes.

Cover crop mixtures are growing in popularity and are often required by public cost-incentive programs. However, few published studies have found mixtures to perform better than monocultures. Mixtures may allow growers to achieve multiple goals and provide insurance that one species will establish and grow during weather extremes. However, mixtures may also prevent growers from fully realizing an individual goal and require additional equipment and management.

Weed Suppression

Weed suppression is often a primary goal of cover crops before soybeans. Cover crops can compete with weeds for vital resources and create a physical barrier to hinder the establishment of weeds. The amount of growth or biomass a cover crop achieves will largely influence the amount of weed control it contributes. Cereal rye’s ability to provide a high amount of biomass makes it a leading option for farmers focused on weed suppression.

The type of weeds being targeted will influence management to maximize weed control. A thoroughly established cover crop can outcompete winter weeds. Terminating the cover crop through mechanical or chemical methods well in advance of the desired planting date can enhance the suppression of winter annual weeds.

With summer annual weeds, the biomass achieved by termination will be the primary influence on weed control. When residue is left on the surface in a no-till system, at least 5,000 lb/acre of dry biomass is ideal for suppressing summer annual weeds. Preemergent herbicide applications are recommended with high-biomass cover crops. The combination of herbicide applications and surface residue can enhance weed control and help reduce herbicide resistance issues.

Soil Moisture Considerations

A living cover crop utilizes soil moisture. In dry conditions leading up to soybean planting, soil moisture levels can be depleted to levels that are suboptimal. If low soil moisture is a concern, it is generally recommended to terminate a cover crop at least two weeks before soybean planting.

Cover crop residue in a no-till system can enhance soil moisture later in the soybean growing season. Increased rainfall penetration and decreased runoff and surface evaporation can occur when adequate residue is left on the soil surface. This can lessen soybean stress during excessively dry years and help protect yields.

Green Bridge Considerations

The green bridge refers to the habitat that cover crops provide for pests that may be transferred to the following cash crop. Scouting and monitoring a cover crop as you approach the next planting season are recommended to determine if pests are a concern. For example, pea weevil can be devastating to soybeans following plantings of Austrian winter pea. Three-cornered alfalfa hopper can be a problem in soybeans that were planted after a cover crop mix that was terminated in close proximity to soybean planting. In addition, cover crops increase the risk for cutworms.

To ensure that problematic insects are identified, scouting strategies should capture pest dynamics in the cover crop mulch. Generally, increasing the time between cover crop termination and planting of the soybean crop can reduce risk. If there is a concern about pest transfer, growers should consider terminating the cover crop three to four weeks before planting.

Planting Difficulties

In a no-till system, residue can create obstacles to uniform soybean planting and adequate seed-to-soil contact. Several types of residue managers are available to help planting equipment work through plant residue. Planting through high levels of cover crop residue may take some practice. The amount of residue and its degree of decay will determine the difficulty of penetration. Delaying termination may create additional residue that could challenge inexperienced growers. Terminating several weeks before planting can allow the cover crop residue to break down and enable better seed-to-soil contact.

Crop Rotation

Growers often have questions about the impact of planting soybeans in rotation with other crops produced in North Carolina. While rotational advantages for soybean production can vary, it is well established that planting the same crop year after year increases the potential for pest problems to intensify. Crop rotation is one of the most effective and profitable pest management tools available.

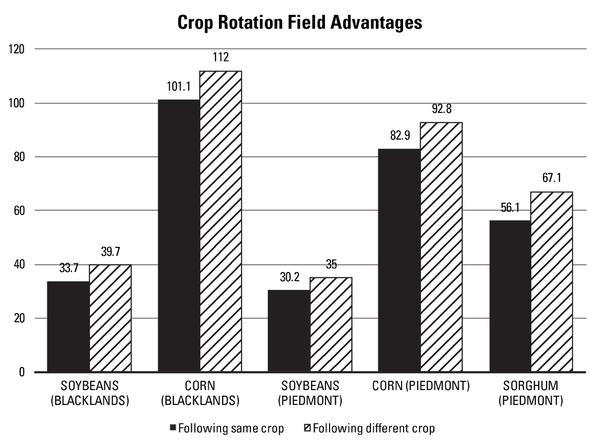

In two long-term rotation studies carried out by NC State in the blacklands (Washington County) from 1972 to 1993 (22 years of data) and in the piedmont (Cleveland County) from 1985 to 1994 (10 years of data), soybean yields were increased by about 5 bu/acre following corn, compared to following soybeans (Figure 4-1). The yield advantage from rotating with another crop was not only observed at the end of the study period but often detected throughout the study period.

Besides the 4-to-5 bu/acre yield penalty for soybeans-following-soybeans, planting continuous soybeans will eventually result in a pest problem. If you plant soybeans back-to-back, be prepared to scout your fields more often and potentially spend more money on pesticide applications. Following are some common problems caused by monocropping.

Nematodes: Soybean cyst nematode populations increase in long-term soybean cropping systems. The only way to monitor the population is through a nematode assay.

Insects: You are more likely to have problems with threecornered alfalfa hopper, dectes stem borer, bean leaf beetle, and stink bugs. Be on the lookout for these when you scout.

Diseases: Diseases that overwinter in crop residue are likely to be a problem in soybeans following soybeans. Keep an eye out for stem canker, cercospora, frogeye leaf spot, and septoria brown spot.

Weeds: Rotating crops lets you diversify your weed management strategy by allowing use of different herbicides and tillage practices. When planting soybeans following soybeans, a good preemergent herbicide with multiple modes of action and overlapping residual herbicide are critical to effective weed control.

Publication date: July 31, 2025

AG-835

Other Publications in North Carolina Soybean Production Guide

- 1. The Soybean Plant

- 2. Variety Selection

- 3. Fertilization and Nutrient Management

- 4. Soil Health, Tillage, Cover Crops, and Crop Rotation

- 5. Planting Decisions

- 6. Weed Management

- 7. Soybean Diseases and Management

- 8. Soybean Nematode Management

- 9. Insect Management

- 10. Water Management in Soybeans

- 11. Late-Season Management, Harvesting, Drying, and Storage

- 12. Soybean Marketing in North Carolina

Recommendations for the use of agricultural chemicals are included in this publication as a convenience to the reader. The use of brand names and any mention or listing of commercial products or services in this publication does not imply endorsement by NC State University or N.C. A&T State University nor discrimination against similar products or services not mentioned. Individuals who use agricultural chemicals are responsible for ensuring that the intended use complies with current regulations and conforms to the product label. Be sure to obtain current information about usage regulations and examine a current product label before applying any chemical. For assistance, contact your local N.C. Cooperative Extension county center.

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.