Introduction

North Carolina’s complex topographic and climatic patterns have provided favorable growing conditions for winegrapes, including most of the important European cultivars (Vitis vinifera), as well as hybrid varieties (crosses between two or more Vitis species), native American varieties (Vitis aestivalis and Vitis labruscana), and muscadines (Vitis rotundifolia). The state ranked number seven in the United States for its 2021 wine production (WineBusiness Analytics 2024) and is one of the fastest-growing viticultural areas of eastern North America. North Carolina’s growing reputation as a wine-producer is demonstrated by the presence of six federally designated American Viticultural Areas (AVA), with a seventh presently under consideration by the US Department of the Treasury.

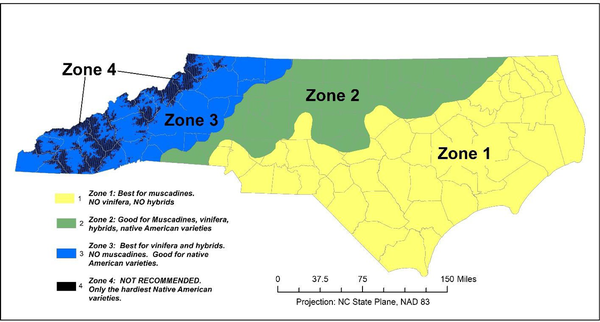

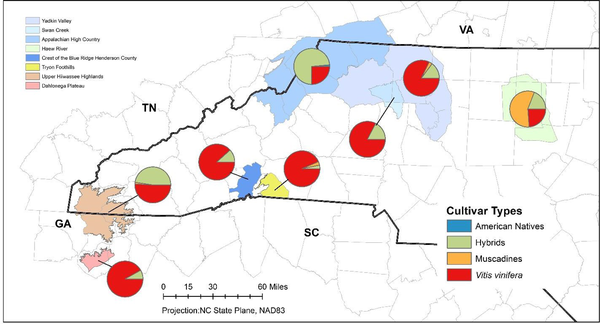

The Viticulture Site Suitability map, published in 2001 by the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, has historically suggested the general pattern of winegrape cultivar distribution in the state. This work divided the state into four zones based on environmental characteristics and recommended winegrape varieties that would be most appropriate for each (Figure 1). We are not aware of any further work to document and verify these recommendations or to modify them based on the last 20 years of wine-growing experience in the state. However, recent wine-growing practice has shown that some muscadine cultivars can be successfully grown on suitable hill sites in Zone 3 when provided sufficient sun exposure and airflow.

The map appeared most recently in the 2015 North Carolina Winegrape Growers Guide unchanged from its original publication. A preliminary review of the map suggested to us that some grapes are being successfully grown outside of the zones in which they are considered appropriate, or grapes are being grown in some zones that are not optimal for their geographic setting, specific climate characteristics, and local disease and pest pressure. A primary goal of this analysis is, therefore, to test the reliability of the site suitability mapping by (1) identifying North Carolina’s presently active vineyards and vineyard-wineries, and (2) determining what cultivars these active operations are growing and how they relate to the site suitability recommendations.

Viticulture is a complex science governed by many environmental aspects, the totality of which are expressed in the French term terroir. This term attempts to relate all natural and human factors that contribute to the successful cultivation of winegrapes and production of quality wines. Our goal is not to analyze the total terroir aspects of North Carolina. Rather, we focus this study on certain aspects of regional temperature conditions that we feel are the key determinants of grape and wine quality. After all, temperature determines the time of annual onset of vine growth, length of the growing season, mean temperature of the growing season, amount of heat accumulated by grapes prior to harvest, and the risk of late spring and early frost events. These temperature factors are easily understood and are important for selecting vineyard sites and winegrape cultivars for initial and replacement plantings. To relate North Carolina’s cultivars to a framework of temperature factors, we have developed four regional models to illustrate and define the above-mentioned temperature regimes across the state.

In addition to describing the overall cultivar distribution patterns in North Carolina, we discuss the implications of climate change for the state’s viticultural future and recommend winegrape cultivars for new and replacement plantings.

Methodology

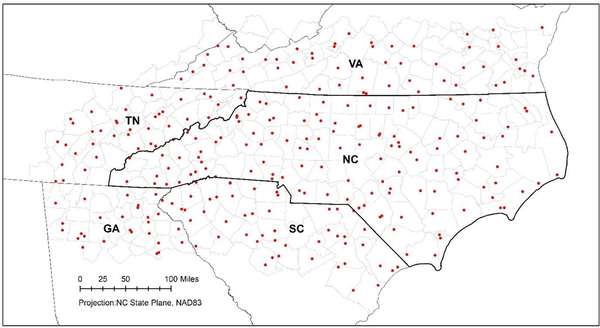

To identify active vineyards and their cultivars, we researched websites and publications of organizations that represent the state’s wine producers, the most important of which are the North Carolina Winegrowers Association, the North Carolina Grape and Wine Council, and the North Carolina Muscadine Grape Association. For vineyards that are not members of these groups, we did more in-depth online searches of specific counties or geographic areas. We also conducted telephone interviews with local Extension agents, chambers of commerce, and individual vineyard owners.

After assembling a list of active vineyards, we researched each one online to ascertain the types of grapes they grow. Most vineyards list grape types on their websites as an indication of the styles of wines they produce or varieties they have for sale. Since our goal has been to correlate cultivars with specific geographic sites, we only consider grapes that are grown at a vineyard with a discernible latitude-longitude location. Wineries that only make wines from purchased grapes are not included in the analysis. Vineyards that grow and sell their grapes are included. Many vineyard-wineries not only grow their own grapes but also purchase grapes from other vineyards. In these cases, we have attempted, by phone conversations with the winegrowers, to exclude the purchased grapes and to include the grapes grown on-site. We did not try to get information on the acreages of each grape type. We rank our listing of cultivars by the number of vineyards that grow them, which is the “frequency of planting.” A frequency of “10” means that 10 vineyards in a geographic area list this grape variety as one they grow. We cannot confirm that our frequency numbers indicate anything about the acreage that a particular grape variety occupies. All data are listed in Appendices 1 to 5.

Using physical addresses, we located the identified vineyards on Google Earth or on imagery from the National Agricultural Imagery Program (NAIP) (U.S. Geological Survey 2018). Since this analysis was meant to be quick and preliminary, we did not digitize the planted vineyard blocks; instead, we manually placed a centroid point among the visible planted blocks as the latitude-longitude location of the vineyard. To assign a physical characteristic, such as elevation or a climate value, we generated a one-mile buffer around each centroid point and extracted values from our climate models to the buffered area. Extracted values were then averaged and assigned to the location.

We feel we have identified most of the vineyards and vineyard-wineries that are presently operational, but it is highly probable that we have missed some. This unintended omission is especially true for the coastal plain region where there are likely to be several muscadine vineyards that do not belong to the statewide organizations or do not advertise via a website. Nevertheless, our evidence suggests that the predominance of the principal muscadine varieties will not likely change based on data from additional vineyards. The websites of a few vineyards and vineyard-wineries (three to five in number) do not list the grape types they grow, and we have not been able to reach the winegrowers, despite numerous attempts. These operations are mainly in the Yadkin Valley, the area of the largest concentration of vineyards and vineyard-wineries in the state. The lack of data from this small group of vineyards will not materially change our interpretations.

To develop models for temperature characteristics, we utilized data from the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) and the Prism Climate Group at Oregon State University. The models for Mean Length of Growing Season and the spring and fall frost indices are based on the 1981 to 2010 climate normals generated by the NCEI. Unfortunately, climate normals for 1991 to 2020 have not been released by the NCEI by the time this publication was written (2022). The models for Mean Growing Season Temperature and for Growing Degree Days are based on the gridded 1991 to 2020 climate normals from the Prism Climate Group at Oregon State University. Processing of data and generation of maps utilized ESRI’s ArcGIS software and its Spatial Analyst extension.

Geographic Distribution of Vineyards and Cultivars

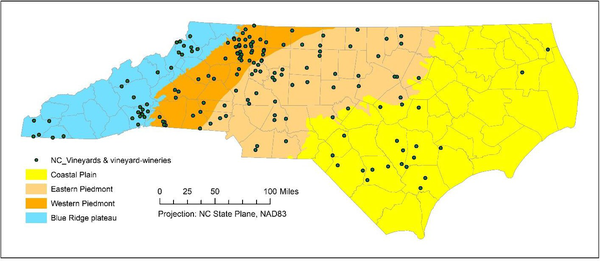

Our research identified 158 active vineyards and vineyard-wineries that fit our analysis criteria (Figure 2) and 127 distinct cultivars being grown in North Carolina (Appendix 1 and Appendix 2). To test the reliability of viticultural site suitability (Figure 1), we show the distribution of cultivars on that map, followed by the distribution on a physiographic map of North Carolina, and finally on a map of North Carolina’s American Viticultural Areas.

Viticulture Suitability Zones

The viticulture site suitability (VSS) map of North Carolina (Figure 1) was originally published in 2001 (Poling and Spayd 2015) with the purpose of recommending the general types of winegrapes that are appropriate in each of four zones across the state. Since publication of the map, there have been two recalculations of US climate normals that affect interpreted climate patterns of the state and possibly boundaries of the original suitability zones, suggesting that the 2001 boundaries require updating. The US National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) calculates climate normals every ten years. The latest normals that are publicly available are for the period 1981 through 2010. An additional weakness of the 2001 map is the definition of Zone 3, which combines the western piedmont with the Blue Ridge plateau. The combination of these two physiographic features masks the profound elevational difference between them and gives a false impression of the varieties of grapes appropriate for each. Finally, the map does not recognize the cold-hardy hybrids developed in the last 20 years that have allowed viticulture to thrive in northern states and that could be appropriate cultivars for the higher elevations of the Blue Ridge plateau.

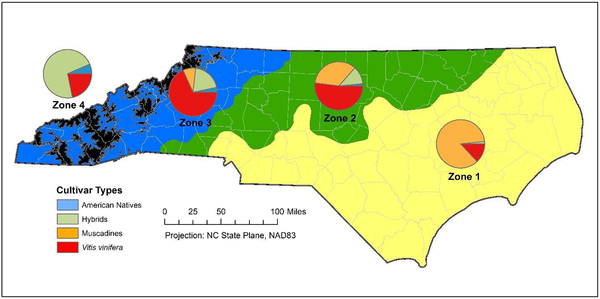

Figure 3 illustrates our interpretation of winegrape species distribution in the 2001 viticulture suitability zones. Specific cultivars are summarized for each zone in Appendix 1.

Muscadine varieties dominate Zone 1, with plantings becoming fewer moving westward across Zone 2 and Zone 3, and non-existent in Zone 4. Vitis vinifera cultivars are relatively rare in Zone 1, are abundant in Zone 2, and are the most frequent plantings in Zone 3; plantings are considerably reduced in Zone 4. Hybrid cultivars are rare in Zone 1 but increase in frequency to the west, becoming the dominant varieties in Zone 4. Native American varieties are relatively rare in Zones 1, 2, and 3, and are at their most prominent in Zone 4, where they still constitute only a small number of plantings.

Despite The VSS’s recommendations against Vitis vinifera and hybrids in Zone 1, we found 16 vinifera cultivars in 16 plantings in the zone, and two hybrid cultivars in two plantings. In Zone 3 where muscadines are specifically not recommended, we found 21 muscadine cultivars being grown in 54 plantings. Zone 4 is recommended for only the hardiest native American cultivars. Our research indicates 16 vinifera cultivars in the zone, 33 hybrids, and only two native American cultivars. Finally, native American cultivars are recommended for Zones 2, 3, and 4, but we found only three native American cultivars in 21 plantings throughout the state.

Zonation of Physiographic Regions

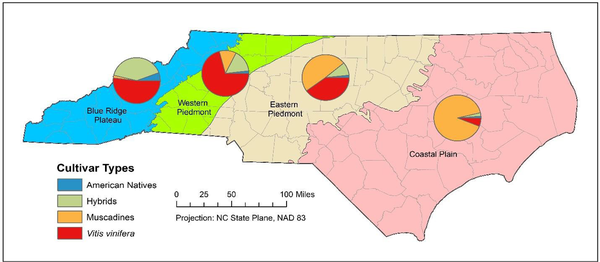

North Carolina comprises four major physiographic regions: coastal plain, eastern piedmont, western piedmont, and Blue Ridge plateau, each distinguished by differences in elevation, topography, and climate. Figure 4 shows the distribution of winegrape cultivars in the physiographic regions. Specific cultivars planted in each region are summarized in Appendix 2.

The dominant varieties on the coastal plain are muscadines, with only a smattering of vinifera plantings, a few hybrids, and a single native American variety. Going west into the eastern piedmont, vinifera cultivars become increasingly important, as do hybrids; muscadine plantings decrease, and native American varieties remain insignificant. In the western piedmont, vinifera cultivars become the most frequently planted varieties; hybrids increase in numbers, with muscadine plantings decreasing significantly. On the Blue Ridge plateau, vinifera plantings are still dominant, with hybrid having increased significantly, muscadines are rarely planted, and native American varieties have achieved their greatest number of plantings, which are relatively insignificant.

American Viticultural Areas

The American Viticultural Area program (commonly referred to as the “AVA” program), is administered by the Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) of the US Department of the Treasury. The program began in 1978 and, to date, has resulted in the designation of 266 AVAs in the United States. Applications for an AVA are made by the winegrowers of a region. The most important part of an AVA petition is a description of the area’s natural environmental characteristics that influence viticulture and an explanation of how these characteristics differ from those of surrounding areas. There are now six AVAs in North Carolina, and a seventh (Tryon Foothills) is under review by the TTB (Figure 5).

Figure 5 and Appendices 3, 4, and 5 summarize the cultivar types in North Carolina AVAs. We include the Dahlonega Plateau AVA of north Georgia in this analysis, as it contrasts so sharply with the adjacent Upper Hiwassee Highlands AVA of North Carolina and north Georgia.

In the Haw River AVA, muscadines are the dominant cultivars, but vinifera and hybrids are also well-represented. In the Yadkin Valley and Swan Creek AVAs, vinifera and hybrids are the predominant cultivars with a few plantings of muscadines and native American varieties. In the adjacent Appalachian High Country AVA, hybrid plantings dominate with vinifera and a few plantings of native American varieties. In the proposed Tryon Foothills AVA, the predominant cultivars are vinifera with a very small number of hybrid plantings and a single planting of muscadines. The adjacent Crest of the Blue Ridge Henderson County AVA is predominantly planted in vinifera cultivars but with a significant number of hybrid plantings. The Upper Hiwassee Highlands AVA of southwestern North Carolina and north Georgia is approximately half vinifera and half hybrids with a small number of muscadine plantings. Finally, the Dahlonega Plateau of north Georgia is planted predominantly in vinifera varieties with a small number of hybrid plantings.

Summary of Cultivar Distribution

The 127 cultivars under cultivation in North Carolina can be classified as follows: 56 are vinifera, 30 are hybrids, 38 are muscadines, and three are native American varieties. Appendices 1 and 2 show the distribution of cultivars. In summary, the 16 most common vinifera cultivars occur in 373 plantings, followed by 13 muscadine cultivars in 172 plantings, five hybrid cultivars in 85 plantings, and three native American cultivars in 21 plantings. The grapes that have attained a worldwide reputation and claim to be the most desired by wine drinkers are the seven vinifera cultivars known as the “Noble Grapes.” They include the red cultivars cabernet sauvignon, merlot, pinot noir, and syrah, and the white cultivars chardonnay, sauvignon blanc, and riesling. All the noble varieties are grown in North Carolina, though pinot noir was found in only one vineyard. The other six are commonly planted in the state.

Geographically, vinifera cultivars are dominant in the western piedmont, with 233 out of a total of 341 plantings. The most frequently planted are merlot, chardonnay, cabernet sauvignon, cabernet franc, viognier, and syrah. Vinifera grapes are also important in the eastern piedmont, where they are present in 101 out of a total of 247 plantings. The most frequently planted are Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Chardonnay, Syrah, and Sauvignon Blanc. On the Blue Ridge plateau, vinifera grapes comprise 96 of 167 plantings, with the dominant cultivars being Cabernet Franc, Riesling, Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Vidal Blanc, Merlot, and Grüner Veltliner. On the coastal plain, there are a total of 81 plantings, of which vinifera cultivars comprise five, with Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah, Tempranillo, and Viognier comprising one planting each.

Wine-making and grape production have a long history in North Carolina. In the mid-nineteenth century, North Carolina had an estimated 25 vineyards and wineries, dominating even the national grape and wine market. Most of the grapes produced stemmed from Vitis rotundifolia (muscadine) cultivars. With the liberation of slaves after the Civil War and North Carolina’s vote to become a “dry state” in 1908, the industry quickly decreased. Prohibition laws from 1920 sealed the deal on the North Carolina grape and wine industry. Even in the 1960s, North Carolina did not have any wineries, although Muscadine grape producers were selling to out-of-state wineries. The first winery to open after prohibition was Duplin Wine Cellars in Rose Hill, North Carolina. The largest winery by volume in North Carolina today is also the state’s oldest operation, founded in 1972. Today, Duplin Wine Cellars produces almost half a million cases of 100% muscadine wine every year.

The first verified vinifera grape planting was established in 1980 on the other end of the state, in Asheville North Carolina, by Biltmore Estates. While Biltmore planted French-American hybrids at the same location in the mid-1970s, the 40-acre vineyard was entirely switched to Vitis vinifera in 1980. The cultivars planted were Chardonnay, Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Merlot. This vineyard still exists, making it the oldest in North Carolina still producing Vitis vinifera. At the time of this publication, the 1980 Chardonnay planting was still producing. After Biltmore, Westbend Vineyards in Lewisville, North Carolina opened as North Carolina’s second V. vinifera-based vineyard-winery in 1988. Fast forward to today, North Carolina has grown tremendously to a multi-billion-dollar grape and wine industry. The persistence of North Carolina winegrowers and their willingness to take risks have made vinifera cultivars the predominantly planted winegrapes in the state and thus have advanced North Carolina’s status as a serious wine-producing region.

Today, the second most frequently planted cultivars in North Carolina are muscadines, which are the most frequently planted grapes on the coastal plain, with an estimated 72 out of a total of 81 plantings. The most important cultivars are Carlos, Noble, Triumph, Supreme, and Tara. In the eastern piedmont, muscadines comprise slightly less than half of all cultivar plantings with 121 of a total of 247 plantings. Noble, Carlos, Magnolia, Nesbitt, Triumph, Tara, Ison, Supreme, and Fry are the most frequently planted. In the western piedmont, muscadines form 37 out of 335 total plantings, with Noble, Carlos, Tara, Triumph and scuppernongs being the most frequently planted. On the Blue Ridge plateau, there are three plantings of muscadine out of a total of 167 total plantings. The cultivars are Katuah muscadines, Katuah scuppernongs, and an unspecified muscadine cultivar. The Katuah varieties are cold-hardy cultivars developed by Jewel of the Blue Ridge Vineyard in Marshall, North Carolina.

Hybrids are the third most frequently planted cultivars in North Carolina. On the Blue Ridge plateau, they comprise 68 out of a total of 167 plantings. The most frequently planted are Seyval Blanc, Catawba, Chambourcin, Marechal Foch, and Marquette. In the western piedmont, there are 52 hybrid plantings out of a total of 335 plantings. Chambourcin and Traminette are the most frequently planted. In the eastern piedmont, there are 21 hybrid plantings out of a total of 247. The most frequently planted are Traminette, Seyval Blanc, and Chardonel. On the coastal plain, there are only two plantings of hybrids, one each of Traminette and Chardonel.

The most surprising of the cultivars are the native American varieties, which were highly recommended by the 2001 site suitability mapping. We found only three cultivars—Norton-Cynthiana, Concord, and Sunbelt—in this category and in very limited geographical distribution. There are six plantings of Norton-Cynthiana in each of the western piedmont and the Blue Ridge plateau, three plantings in the eastern piedmont, and one planting on the coastal plain. There are three plantings of Concord on the Blue Ridge plateau and one planting in the eastern piedmont. There is one planting of Sunbelt in the eastern piedmont.

To compare cultivars in North Carolina’s AVAs, refer to Appendices 3, 4, and 5. We have divided the AVAs into three categories based on geographic location. The Northern Tier (Appendix 4) consists of the Appalachian High Country, Yadkin Valley, Swan Creek, and Haw River AVAs, and the areas have been listed in the table with the adjacent AVAs in their geographic positions from west to east. The Central Tier of AVAs (Appendix 5) includes the Crest of the Blue Ridge Henderson County and the proposed Tryon Foothills. The Southern Tier comprises the Upper Hiwassee Highlands and the Dahlonega Plateau AVAs.

Regional Temperature Models for Vineyard Site Evaluation and Cultivar Selection

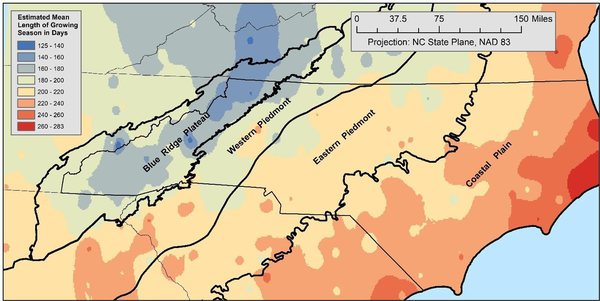

Mean Length of Growing Season

The length of a vineyard site’s growing season is defined as the number of days between the last spring frost and the first fall frost, based on a temperature of 32°F. To produce quality wine, grapes should be fully ripe at the time of harvest. Determining the mean length of growing season is an important metric for selecting a vineyard site and deciding on the appropriate grapes to plant. Many authors have suggested ranges of growing season length for optimum ripening of grapes. Average values fall between 170 to 190 days (G. Jones 2015). A minimum growing season of 165 days is essential (Jordan, et al. 1980). Sites with 165 to 180 days may be marginal. A growing season of 180 days or greater is preferable.

To generate our model of Growing Season Length, we utilized 284 NCEI weather monitoring stations throughout North Carolina and within a 75-mile buffer around the state’s boundaries (Figure 6). These stations all have mean values of the length of growing season based on the NCEI 1981 to 2010 climate normals. As might be expected, growing season length varies with topography. The lower elevations of the coastal plain have the longest growing season, the central parts of the state have intermediate lengths, and the higher elevations of the western part of the state have the shortest season.

To generate a more complete interpretation of length of growing season, we have converted the observed values shown in Figure 6 into an indiscrete, continuous field model using an inverse distance weighted interpolation (Figure 7). From the resulting model, we have assigned estimated mean growing season lengths to each of the active vineyards using an average of all modeled values within a 1-mile radius of a vineyard’s manually assigned center point. Our estimated length of growing season throughout North Carolina ranges from 134 days on the highest peaks of the Blue Ridge plateau to 283 days at the lowest elevations of the coastal plain. The estimated mean length of growing season for North Carolina’s active vineyards ranges from 154 to 239 days. Since grape varieties vary in their rates of maturation, it is essential that the winegrower plant grapes that will ripen during the vineyard site’s growing season.

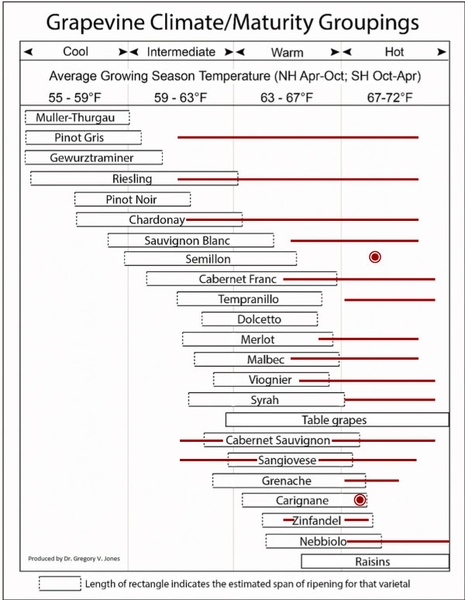

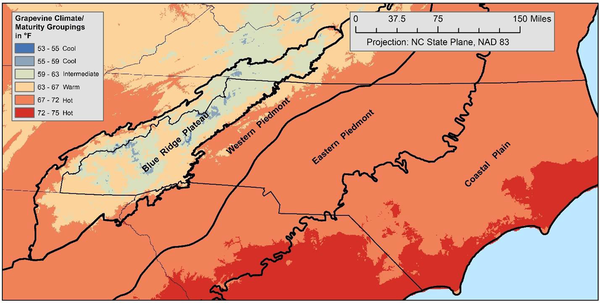

Mean Growing Season Temperature

Quality wine production is generally limited worldwide to mean growing season temperatures in the range of 55°F to 70°F (G. Jones 2015). The Grapevine Climate/Maturity Groupings chart of Professor Gregory Jones shows optimal mean growing season temperatures for some of the best-known winegrape cultivars based on four temperature ranges (cool, intermediate, warm, and hot) that occur in vineyard climates worldwide (Figure 8). Though the cultivars on the chart can be grown outside of the optimal ranges, they tend to produce the best wines in the temperature ranges shown. The classification can be used to suggest cultivars that might be appropriate for new vineyards or for new plantings in areas with similar growing season temperatures.

Unfortunately, the Jones Maturity Groupings chart illustrates only vinifera varieties and tells us nothing about hybrid, muscadine, or native American grapes that are also important to North Carolina. By plotting the mean growing season temperatures of the vinifera grapes growing in the state on the Jones chart, we can assume that many of the vinifera grapes planted in North Carolina may be in areas that are too warm for their ripening characteristics (Figure 8). The heavy red lines represent the mean growing season temperature ranges for vinifera presently under cultivation in North Carolina. Two encircled red points represent the value for cultivars with only one planting.

Using the Prism Climate Group’s gridded 1991 to 2020 temperature normals, we have generated a model of mean growing season temperature for North Carolina (Figure 9). All four of Jones’s Maturity Groupings occur in the state, with the cool, intermediate, and warm regions in the western piedmont and the Blue Ridge plateau, and the hot areas in the eastern piedmont and coastal plain.

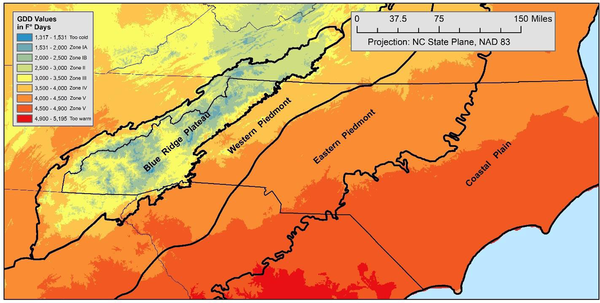

Growing Degree Day Zonation

Plants begin their annual growth cycle when the mean daily temperature reaches a critical base value, which in the case of grapes is generally assumed to be 50°F (10°C). In the northern hemisphere this level is normally attained in April, with the growth cycle then extending, on average, through October. A plant’s ability to reach full maturity is based on the amount of heat the plant is exposed to over the growing season. Agronomists estimate the accumulated heat by calculating and summing heat units called growing degree days (GDD).

The technique of GDD zonation was popularized in viticulture by Amerine and Winkler in their renowned classification of California vineyards published in 1944. They divided the state’s viticultural areas into five categories known as “Winkler Regions” based on their ranges of GDD units and assigned grapes to them based on the varieties’ optimal development. We use the term “GDD zones” rather “Winkler regions” since the California classification is presently under recalculation. Recent work in the western United States (Jones, et al. 2010) and Australia (Hall and Jones 2010) suggests a lower limit of 1500 F° units for Region I and an upper limit of 4900 F° units for Region V.

Further work has divided Region I into a Region Ia, for early-ripening cultivars, mainly hybrids, and Region Ib for early-ripening cultivars, mainly V. vinifera (Table 1).

| GDD in F° Units | Growth Zone | Climate Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| < 1500 | Too cold for grapes | Cold |

| 1500–2000 | Zone Ia | Cool |

| 2000–2500 | Zone Ib | Cool |

| 2500–3000 | Zone II | Intermediate |

| 3000–3500 | Zone III | Intermediate |

| 3500–4000 | Zone IV | Warm |

| 4000–4900 | Zone V | Warm |

| >4900 | >Zone VI | Hot |

Our model (Figure 10) indicates the highest GDD values for North Carolina occur on the coastal plain and decrease westward, with intermediate values in the eastern and western piedmont regions, and the lowest values on the Blue Ridge plateau. All five Winkler regions occur in North Carolina, with a total range of 1237–4900 GDD units. The range of GDD units for active North Carolina vineyard sites is 1939–4722.

The geographic areas in which these vineyards are located, including AVAs and non-AVA areas, are found in all defined GDD zones (Table 1). Zone I (below 2500 GDD) was found exclusively in the Appalachian High Country AVA and the very highest peaks of the Blue Ridge plateau. The GDDs of Zone I can be compared to those of winegrowing regions of the Rhine Valley or the Champagne region of France.

Most vineyards in North Carolina are in Zones III, IV, and V. Vineyards of Zone III are in higher elevations of the Crest of the Blue Ridge Henderson County AVA and in the Upper Hiwassee Highlands. This zone can be compared with growing regions of the Rhone Valley. Vineyards in Zones IV and V are in the Yadkin Valley, Swan Creek, and Haw River AVAs and most piedmont vineyards outside of AVAs. The average GDD of Zone IV is similar to regions in Spain and Italy. Approximately 54% of investigated vineyards were in regions that accumulate an average of 4000 or greater GDD (Zone V) units. This zone surprisingly includes the vineyards in the proposed Tryon Foothills AVA, which is located at the base of the Blue Ridge escarpment. The GDD accumulation in this region is comparable to winegrowing regions in North Africa.

Though it is interesting to make the above comparisons with international viticulture areas, it’s worth noting that the Winkler index was developed for the Mediterranean and semi-arid climates of California and not for the warm and mixed humid climate of North Carolina. Therefore, GDD zone analysis should be viewed as one of many climatic characteristics that contributes to the overall terroir conditions of North Carolina. While the GDD index might recommend certain cultivars for optimal ripening, North Carolina’s low winter temperatures, late spring frosts, humid climate, and high average annual precipitation can be highly limiting factors for sustainable vineyards. For example, cultivars such as Riesling, Pinot Noir, Pinot Grigio, Zinfandel, Malbec or even Chardonnay are recommended for Zones I and II. Of these, Riesling, Malbec, and Chardonnay are found frequently in North Carolina vineyards in GDD zones Ib to V. All areas of western North Carolina can be affected by frequent late spring frost and freeze events, which make the growing of early bud-breaking cultivars (such as Chardonnay) challenging. Summer humidity and heavy rainfalls facilitate the spread of foliar and fruit diseases and hinder development of microclimates under the canopies. These conditions create problems in cultivars with tight clusters and thin berry skins (such as Riesling). Such cultivars are usually harvested before desired maturity because of extensive deterioration in the vineyard. On the other hand, cultivars such as Cabernet Franc and Merlot are not recommended for Zones IV and V but produce well in those zones in North Carolina. Cultivars such as Montepulciano or Sangiovese are challenging but can be successfully grown in the state’s Zones IV and V.

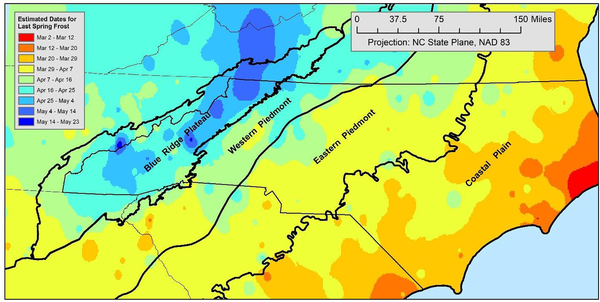

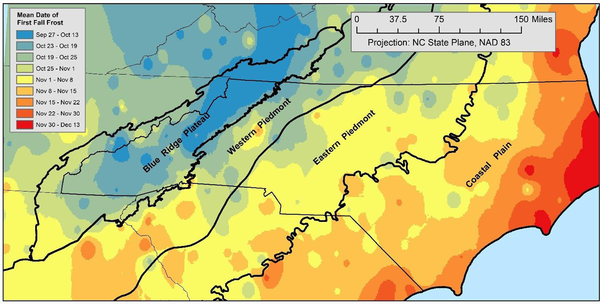

Spring and Fall Frost Indices

Late spring frost events are a great danger to winegrapes, shortly before or after bud break. In all western North Carolina regions, winegrowers should always consider the risk of frosts when selecting a vineyard site and in choosing specific cultivars for a site. Our model utilized the NCDC 1981 to 2010 climate normals from the 284 weather-monitoring stations in Figure 6 and is based on the average dates for the last spring frost event and the first fall frost event. The average date for these events as published in the NOAA datasets is the so-called “50% probability date for a 32°F frost event.”

Using an inverse distance weighted interpolation, we converted the discrete data points into continuous field data models (Figure 11 and Figure 12). The colored areas on the map represent mean date ranges when spring or fall frost events can be expected. In the low elevations of the coastal plain, the latest spring frost events can be expected from March 2 to April 7, in the eastern and western piedmont from March 29 to April 25, and on the Blue Ridge plateau from April 16 to May 23. The first fall frost on the coastal plain can be expected from October 25 to December 13, in the eastern piedmont from October 19 to November 8, in the western piedmont from October 19 to November 15 and on the Blue Ridge plateau from September 27 to October 25.

Bud break typically begins when the mean daily temperature in the vineyard reaches or exceeds 50°F. At that point, buds on the vines begin to swell, and shoots and leaves emerge.

Veraison is the onset of grape ripening or the last stage in the vine growth cycle. The berries begin to change physically and chemically. The skins change color, the berries soften, flavor compounds begin to develop, sugar content increases, and acid level decreases. Veraison is a sign that harvest time is near.

Climate Change and Viticulture in North Carolina

Establishment of a vineyard and winery is often a multi-million-dollar enterprise that requires a minimum vision of two decades into the future. Climate change therefore plays a major role in today’s selection of grape cultivars and vineyard sites that will withstand rapidly changing weather patterns that are predicted for the future in the southeastern United States. The Fourth National Climate Assessment projects an increase of warmer nights (temperatures greater than 75°F) in most parts of North Carolina to 30 to 50 nights per year by 2050, a drastic increase of 100% to 200% from the current 30-year average. At the same time, increased heavy rainfalls will cause more flooding and erosion of vineyard soils, an already existing problem in the Southeast (Wolf, Smith and Giese 2020).

Increased rainfalls will also hinder optimal vineyard management and spray programs, most likely increasing severity of pathogens in vineyards across North Carolina. By the end of the twenty-first century, another shift of plant hardiness zones is projected, with most of the piedmont and southern foothills of the state shifting into plant hardiness zone 8b (currently 8a). This shift is projected for the whole state of North Carolina, including the mountain regions (Carter, et al. 2018). Under this scenario, vector-borne diseases for humans and plants (such as Pierce’s Disease) will be more common and found in areas which had low incidence in the past. Extreme weather events such as tropical storms, flooding, and droughts are expected to increase in the Southeast over the next 30 years. The number of heavy rainfalls, spring frosts, and droughts in North Carolina has already been problematic for vineyards, widely affecting the grape-growing industry in the past five years. It is unclear what effects those changes will have on grape maturity and grapevine performance in North Carolina. However, some Vitis vinifera winegrape cultivars already struggle to perform under the current humid, hot, and wet conditions, and will most likely become more problematic for new vineyard plantings. A good portion of the North Carolina grape and wine industry will likely continue to increase acreage of better adapted French-American hybrids or pure American cultivars and decrease acreage of Vitis vinifera cultivars in the future.

Winegrape Cultivar Recommendations for North Carolina

Choosing cultivars is always a complex decision. To be profitable, North Carolina vineyards must consider climatic conditions in addition to sound business models, attention to customer preferences, and the possible need and willingness to educate the consumer about new grape cultivars. Temperature aspects discussed in this study are only one among many factors in this very complex equation and, as mentioned above, other climatic factors such as precipitation, humidity, and diurnal temperature range will also affect cultivar performance. In Table 2, we have followed Poling and Spayd (2015) and developed an overview of cultivars that perform well in North Carolina from a vineyard point of view. In Table 3 we present cultivars that are commonly grown in North Carolina but are typically challenging in a vineyard.

These recommendations are certainly not complete. Cultivars that are thin-skinned, tight-clustered, early bud breaking, or highly susceptible to Pierce’s Disease are generally challenging to grow in North Carolina. Those cultivars encompass most Italian and Spanish V. vinifera cultivars. Less well-known V. vinifera cultivars such as Petit Verdot or Petit Manseng perform well in North Carolina due to late bud break, mid-season ripening, and loose cluster structure. French-American hybrids generally have a higher chance of success in North Carolina. Cultivars such as Chambourcin, Vidal Blanc, Traminette, and Chardonel are known throughout the North Carolina industry as cultivars with good growing and ripening qualities. These cultivars are increasingly used in all winegrape growing regions in the state. Cultivars such as Frontenac and Seyval Blanc are receiving increasing interest throughout the North Carolina grape and wine community.

One prime example of a challenging and widely grown cultivar in North Carolina is Riesling, which has very tight and thin-skinned clusters. These characteristics make this cultivar highly susceptible to bunch rots, especially sour rot. In most years in North Carolina, Riesling is harvested prematurely based on bunch rot incidence rather than berry chemistry.

Pierce’s Disease is one the major threats to the grape and wine industry. This disease, transmitted by insect vector, frequently leads to die-back in North Carolina vineyards, especially in the Yadkin Valley foothills. It can be assumed that with milder winters and warmer summers this disease will eventually be found even in the higher elevations of the mountains. All V. vinifera and most French-American hybrid winegrape cultivars are susceptible to Pierce’s Disease. Currently, the only management method is the use of insecticides to control the insect vectors.

However, new hybrid winegrape cultivars resistant to Pierce’s Disease, released in 2019 by the University of California-Davis breeding program, could have potential for the future viticulture industry in North Carolina. These hybrid cultivars are presently being tested in a trial in the Yadkin Valley AVA. The red cultivars are Camminare Noir, Paseante Noir, Errante Noir, and the whites are Ambulo Blanc and Caminante Blanc. Other hybrid winegrape cultivars released in 2016 by the University of Arkansas breeding program, such as Enchantment and Opportunity, might have potential but are not widely planted in North Carolina at this time.

| Type | Cultivars | Color | Yield Potential | Zone | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitis vinifera cultivars. [1] | Cabernet Franc | Red | Moderate | II–V | Suited for almost all growing regions in NC. |

| Petit Verdot | Red | Moderate to high | II–V | High yield potential and can achieve superior berry composition in NC. | |

| Petit Manseng | White | Moderate | II–IV | Great yield potential and is less affected by sour rot, compared to other whites. | |

| Viognier | White | Moderate | II–IV | Better suited to NC due to the relatively loose cluster compared to Riesling, Chardonnay or Gewüerztraminer. | |

| Montepulciano | Red | Moderate | IV–V | Suited for the warmer regions of the Yadkin Valley and the foothills. | |

| French-Amserican hybrids. [2] | Chambourcin | Red | High | II–V | One of the easiest winegrapes to grow in western NC. Very high yield potential and can be made in single-variety wine or used to blend. Achieves great color and superior ripeness in most climate zones in western NC. |

| Traminette | White | Moderate | I–V | Relatively new white French-American hybrid that can function for blending and single-varietal wines. May even be able to grow in Region I. | |

| Cardonel | White | Moderate to High | II–V | Becoming more popular in NC. A great alternative to Chardonnay, has higher yield potential and excellent berry composition. | |

| Vidal Blanc | White | Moderate to High | II–V | Becoming more and more popular in NC. High yield potential, great berry composition, and ease of management. | |

| Lenoir/Black Spanish | Red | Moderate to High | III–V | Hybrid with dark, black juice. Pierce’s Disease resistant. Grapes can be used to blend for color or even to make single varietal wine. | |

| Native American cultivars. [3] | Carlos | White | High | IV–VI | White muscadine cultivar that has potential to be grown in suited areas in western NC. Muscadines are not very cold hardy and site selection will impact success. Easy to grow, high yield potential. |

| Noble | Red | High | IV–VI | Red muscadine cultivar typically used for wine making. | |

| Norton/Cynthiana | Red | Moderate–High | I–IV | Grown in the Yadkin Valley as well as in the Appalachian Mountains. High yield potential. Great for stand-alone wines and blends. | |

| Niagara | White | Moderate | I–IV | Not very common in NC but has potential. | |

| Catawba | Red | Moderate | I–IV | Not very common in NC but has potential. |

[1] Also called European winegrapes. Cultivars are based on crossings between European grapevines of the species Vitis vinifera. Commonly grafted to American rootstocks to control nematodes, vigor, and grape phylloxera. Those cultivars are also susceptible to Pierce’s Disease. ↲

[2] Crosses between V. vinifera-based cultivars and American grapevines. This group is generally well suited for western North Carolina and should be part of every vineyard layout or plan in the region. This table lists the most common French-American hybrids grown in North Carolina. Several breeding programs in the eastern United States are actively developing new hybrid grapes. We recommend frequently consulting with them and the local viticulturist on newest developments. ↲

[3] Grapes that are 100% of American heritage. ↲

The emergence of the Appalachian High Country AVA is an interesting and surprising development due to the high elevation of the terrain with its shorter growing season and higher incidence of late spring and early fall frosts. Proper site selection is essential for establishing successful vineyards in this region. Sites should be located in rain-shadows, provide good airflow, and have sufficient sun exposure. Good site selection combined with appropriate choice of cultivars increases potential for success. Cold-hardy cultivars recently developed for use in the upper Midwest and New England have opened the possibility of routinely growing grapes at elevations exceeding 3000 feet. Though several early pioneering vineyards in the Appalachian High Country have permanently closed, there is an emerging group of younger entrepreneurs and investors that is taking up the challenges of opening this new viticultural province.

Table 3. Winegrape cultivars that require rigorous management or are frequently prone to problematic disease or weather events in western North Carolina, including piedmont and foothills.

|

Type |

Cultivars |

Color |

Yield Potential |

Zone |

Comments |

|

Vitis vinifiera cultivars. |

Chardonnay |

White |

Moderate |

II–V |

Frequently prone to spring frost damage and sour rot in NC. Site selection is essential for successful plantings. |

|

Merlot |

Red |

Moderate to High |

II–V |

Most widely planted winegrape cultivar in NC. Early bud break often results in considerable spring frost damage in NC. |

|

|

Cabernet Sauvignon |

Red |

Moderate |

II–V |

Extremely high vigor, long ripening period makes this cultivar challenging in NC, even on vigor restricting rootstocks. |

|

|

Sauvignon Blanc |

White |

Moderate |

II–V |

Prone to sour rot, like most tight clustered, thin-skinned white cultivars in NC. |

|

|

Riesling |

White |

Low–Moderate |

I–IV |

Probably the cultivar that attracts sour rot the most. Typically must be harvested before optimal ripeness in NC. |

|

|

Gruener Veltiner |

White |

Low–Moderate |

I–IV |

Sour rot can be a problem. |

|

|

Sangiovese |

Red |

Moderate to High |

IV–V |

Vigor and cluster size can become a problem when managing diseases. |

|

|

Pinot Gris/Noir |

White/Red |

Moderate |

IV–V |

Tight clusters make them highly susceptible to Pierce’s Disease. Not very cold hardy. A challenge to grow in NC. |

|

|

French–American hybrids and Native American grapes. |

Blanc-du-Bois |

White |

Moderate |

III–V |

Resistant to Pierce’s Disease but has problems with other diseases common in NC. |

|

Concord |

Red |

High |

II–V |

Can express uneven ripening in the warmer regions of NC. |

Conclusions

North Carolina has a wide range of climate zones and provides the potential environment for a wide variety of grape cultivars. Growing season lengths in the state will accommodate very early- to very late-ripening grape varieties. Our mean growing season temperatures span the range in which quality wine production occurs worldwide. Heat accumulation, as measured by growing degree days, covers the entire spectrum of the Winkler Regions/GDD Zones. However, all areas of the state suffer from the risks posed by late spring frost events, heavy and frequent rainfalls, and high humidity in summer with resulting year-round disease pressure. In addition to these limitations, catastrophic weather events such as hurricanes, tornadoes, and concomitant landslides also create challenges.

We have stressed the relationship of climate to topography and feel there is a strong correlation of winegrape cultivars to North Carolina’s four major physiographic regions. Climate change is likely to increase average length of the growing season, mean growing season temperature and GDD values, and parts of North Carolina’s mountains will become more interesting for future cultivation of V. vinifera and muscadines. The complex geomorphology and climate conditions of western North Carolina (especially the western piedmont and Blue Ridge plateau regions) provide notable opportunities for growth of many different winegrapes. Cultivars such as Chardonnay, Merlot, Malbec, and Riesling are grown in larger quantities in western North Carolina but are challenging to manage. Other European cultivars, such as Petit Verdot, or French-American hybrids such as Chambourcin, Vidal Blanc, Chardonel, or Seyval Blanc, have become increasingly prominent in the western part of the state due to their better performance and less intensive management. Moreover, western North Carolina has significant plantings of native American cultivars such as Norton-Cynthiana.

When using the information in this study, it is important to be aware of its imperfections. Though we have tried to be as complete as possible, we know there are vineyards missing and some vineyards that are included may now be out of business. We certainly have missed some cultivars that are presently under cultivation and may have included others that are no longer planted.

A second caveat concerns our use of computer models. These depend on many assumptions and interpolation of values between widely-spaced data points. Though they may suggest important trends, models are never totally correct. The complex topography of North Carolina presents many geomorphic situations that hide subtle climate conditions undetectable at the resolution of today’s digital elevation models and gridded climate data. High resolution data that the state is presently collecting may present opportunities if the data are made easily available to the public for research.

Our primary goal in this study has been to provide a preliminary framework of North Carolina’s winegrape geography. To make proper recommendations for future cultivars in North Carolina, it is important to know which cultivars are being grown at the present time and how successful these are in the individual vineyard sites. Though it may not be perfect, our analysis is a beginning towards this goal. Major improvement will be the addition of digital vineyard blocks, acreages of each cultivar type in those blocks, and an assessment of the success of individual cultivars. These enhancements will give a truer accounting of the importance of the various cultivars in North Carolina’s viticultural future.

Appendix 1: Alphabetical Listing of Cultivars in North Carolina Viticulture Suitability Zones

Key to Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | ||

| NC Viticulture Suitability Zones | Zone 1 | |

| Zone 2 | ||

| Zone 3 | ||

| Zone 4 | ||

| Grape Variety | Vitis vinifera | VV |

| Hybrid | H | |

| Muscadine | M | |

| American Native | AN | |

| Cultivars | Frequency | Variety | Zone 1 | Zone 2 | Zone 3 | Zone 4 |

| Aglianico | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Albariño | 2 | VV | 2 | |||

| Albemarle | 1 | M | 1 | |||

| Arandell | 3 | VV | 3 | |||

| Aromella | 1 | H | 1 | |||

| Assyrtiko | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Ayapi | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Baco Noir | 1 | H | 1 | |||

| Barbera | 3 | VV | 1 | 2 | ||

| Black Beauty | 1 | M | 1 | |||

| Cabernet Franc | 51 | VV | 1 | 15 | 33 | 2 |

| Cabernet Sauvignon | 48 | VV | 1 | 16 | 29 | 2 |

| Carignan | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Carlos | 38 | M | 22 | 12 | 4 | |

| Carménère | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Catawba | 7 | H | 1 | 4 | 2 | |

| Cayuga White | 4 | H | 4 | |||

| Chambourcin | 34 | H | 13 | 20 | 1 | |

| Chardonel | 6 | H | 1 | 3 | 2 | |

| Chardonnay | 48 | VV | 15 | 31 | 2 | |

| Cinsault | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Concord | 4 | AN | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Corot Noir | 4 | H | 3 | 1 | ||

| Cowart | 3 | M | 2 | 1 | ||

| Crimson Cabernet | 1 | H | 1 | |||

| Darlene | 3 | M | 2 | 1 | ||

| Dixie Red | 3 | M | 1 | 2 | ||

| Doreen | 5 | M | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Dornfelder | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Farrer | 1 | M | 1 | |||

| Fleurtai | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Frontenac | 1 | H | 1 | |||

| Frontenac Gris | 1 | H | 1 | |||

| Fry (unspecified) | 6 | M | 1 | 4 | 1 | |

| Fry (Black) | 1 | M | 1 | |||

| Fry (Early) | 2 | M | 2 | |||

| Fry (Late) | 2 | M | 2 | |||

| Fry (White) | 2 | M | 2 | |||

| Golden Muscat | 1 | H | 1 | |||

| Granny Val | 1 | M | 1 | |||

| Grenache | 4 | VV | 3 | 1 | ||

| Grüner Veltliner | 4 | VV | 3 | 1 | ||

| Hall | 1 | M | 1 | |||

| Hunt | 2 | M | 1 | 1 | ||

| Ison | 6 | M | 2 | 3 | 1 | |

| Itasca | 2 | H | 1 | 1 | ||

| Jumbo | 4 | M | 3 | 1 | ||

| Katuah Muscadine | 1 | M | 1 | |||

| Katuah Scuppernong | 1 | M | 1 | |||

| La Crosse | 1 | H | 1 | |||

| Landot Noir | 2 | H | 1 | 1 | ||

| Lane | 6 | M | 5 | 1 | ||

| Lemberger | 2 | VV | 2 | |||

| Léon Millot | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Magnolia | 13 | M | 6 | 6 | 1 | |

| Malbec | 11 | VV | 6 | 5 | ||

| Malvasia Bianca | 2 | VV | 1 | 1 | ||

| Marechal Foch | 4 | H | 4 | |||

| Marquette | 5 | H | 3 | 2 | ||

| Marsanne | 1 | H | 1 | |||

| Mavron | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Merlot | 53 | VV | 19 | 34 | ||

| Montepulciano | 6 | VV | 2 | 4 | ||

| Moschofilera | 2 | VV | 1 | 1 | ||

| Mourvedre | 3 | VV | 2 | 1 | ||

| Muscadine (unspecified) | 14 | M | 2 | 10 | 2 | |

| Muscat | 2 | VV | 1 | 1 | ||

| Muscat Canelli | 2 | VV | 2 | |||

| Muscat Ottonel | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Nebbiolo | 3 | VV | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Negroamaro | 2 | VV | 1 | 1 | ||

| Nesbitt | 15 | M | 8 | 5 | 2 | |

| Niagara | 1 | H | 1 | |||

| Noble | 37 | M | 18 | 14 | 5 | |

| Noiret | 2 | H | 2 | |||

| Norton-Cynthiana | 16 | AN | 1 | 3 | 11 | 1 |

| Pam | 4 | M | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| Paulk | 4 | M | 4 | |||

| Petit Manseng | 12 | VV | 2 | 10 | ||

| Petit Pearl | 1 | H | 1 | |||

| Petit Sirah | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Petit Verdot | 31 | VV | 10 | 20 | 1 | |

| Pinot Grigio/Gris | 14 | VV | 7 | 6 | 1 | |

| Pinot Noir | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Pinotage | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Prairie Star | 1 | H | 1 | |||

| Ravat 34 | 1 | H | 1 | |||

| Regent | 4 | H | 1 | 3 | ||

| Ribolla Gialla | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Riesling | 21 | VV | 4 | 15 | 2 | |

| Rkatsiteli | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Robert S. Lee | 1 | M | 1 | |||

| Roditis | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Roussanne | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Sagrantino | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Sangiovese | 13 | VV | 4 | 8 | 1 | |

| Saperavi | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Sauvignon Blanc | 10 | VV | 5 | 5 | ||

| Scarlet | 3 | M | 3 | |||

| Scuppernong | 6 | M | 2 | 3 | 1 | |

| Semillon | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Seyval Blanc | 16 | H | 2 | 8 | 6 | |

| St. Croix | 2 | H | 1 | 1 | ||

| Soreli | 1 | H | 1 | |||

| Southern Home | 2 | M | 1 | 1 | ||

| Steuben | 2 | H | 2 | |||

| Sugargate | 1 | M | 1 | |||

| Summit | 5 | M | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Sunbelt | 1 | AN | 1 | |||

| Supreme | 11 | M | 6 | 4 | 1 | |

| Sweet Jenny | 2 | M | 2 | |||

| Syrah | 15 | VV | 1 | 8 | 6 | |

| Tannat | 4 | VV | 1 | 3 | ||

| Tara | 12 | M | 5 | 5 | 2 | |

| Tempranillo | 3 | VV | 1 | 2 | ||

| Thiakon | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Touriga Nacional | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Traminette | 24 | H | 1 | 6 | 13 | 4 |

| Triumph | 12 | M | 8 | 3 | 1 | |

| Valvin Muscat | 1 | H | 1 | |||

| Vermentino | 4 | VV | 2 | 2 | ||

| Vidal Blanc | 12 | VV | 3 | 6 | 3 | |

| Villard Noir | 1 | H | 1 | |||

| Viognier | 23 | VV | 1 | 11 | 11 | |

| Welder | 1 | M | 1 | |||

| Xynesteri | 1 | VV | 1 | |||

| Zinfandel | 4 | VV | 4 |

Appendix 2: Alphabetical Listing of Cultivars in North Carolina Physiographic Provinces

Key to Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Physiographic Provinces | Coastal Plain | CP |

| Eastern Piedmont | EP | |

| Western Piedmont | WP | |

| Blue Ridge Plateau | BRP | |

| Blue Ridge Escarpment | BRE | |

| Grape Varieties | Vitis vinifera | VV |

| Hybrid | H | |

| Muscadine | M | |

| American Native | AN |

| Cultivars | Frequency | Variety | CP | >EP | WP | BRP | BRE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aglianico | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Albariño | 2 | VV | 2 | ||||

| Albemarle | 1 | M | 1 | ||||

| Arandell | 3 | VV | 3 | ||||

| Aromella | 1 | H | 1 | ||||

| Assyrtiko | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Ayapi | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Baco Noir | 1 | H | 1 | 1 | |||

| Barbera | 3 | VV | 3 | ||||

| Black Beauty | 1 | M | 1 | ||||

| Cabernet Franc | 51 | VV | 1 | 9 | 27 | 14 | 3 |

| Cabernet Sauvignon | 48 | VV | 1 | 9 | 28 | 10 | |

| Carignan | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Carlos | 38 | M | 16 | 18 | 4 | ||

| Carménère | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Catawba | 7 | H | 1 | 6 | 3 | ||

| Cayuga White | 4 | H | 3 | 1 | |||

| Chambourcin | 34 | H | 8 | 20 | 6 | ||

| Chardonel | 6 | H | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Chardonnay | 48 | VV | 9 | 30 | 9 | ||

| Cinsault | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Concord | 4 | AN | 1 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Corot Noir | 4 | H | 3 | 1 | |||

| Cowart | 3 | M | 2 | 1 | |||

| Crimson Cabernet | 1 | H | 1 | ||||

| Darlene | 3 | M | 3 | ||||

| Dixie Red | 3 | M | 1 | 2 | |||

| Doreen | 5 | M | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Dornfelder | 1 | VV | 1 | 1 | |||

| Farrer | 1 | M | 1 | ||||

| Fleurtai | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Frontenac | 1 | H | 1 | 1 | |||

| Frontenac Gris | 1 | H | 1 | 1 | |||

| Fry (unspecified) | 6 | M | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Fry (Black) | 1 | M | 1 | ||||

| Fry (Early) | 2 | M | 2 | ||||

| Fry (Late) | 2 | M | 1 | 1 | |||

| Fry (White) | 2 | M | 2 | ||||

| Golden Muscat | 1 | H | 1 | 1 | |||

| Granny Val | 1 | M | 1 | ||||

| Grenache | 4 | VV | 2 | 2 | |||

| Grüner Veltliner | 5 | VV | 5 | 1 | |||

| Hall | 1 | M | 1 | ||||

| Hunt | 2 | M | 1 | 1 | |||

| Ison | 6 | M | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Itasca | 2 | H | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Jumbo | 4 | M | 3 | 1 | |||

| Katuah Muscadine | 1 | M | 1 | ||||

| Katuah Scuppernong | 1 | M | 1 | ||||

| La Crosse | 1 | H | 1 | 1 | |||

| Landot Noir | 2 | H | 1 | 1 | |||

| Lane | 6 | M | 4 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Lemberger | 2 | VV | 2 | ||||

| Léon Millot | 1 | VV | 1 | 1 | |||

| Magnolia | 13 | M | 2 | 10 | 1 | ||

| Malbec | 11 | VV | 3 | 7 | 1 | ||

| Malvasia Bianca | 2 | VV | 1 | 1 | |||

| Marechal Foch | 4 | H | 4 | ||||

| Marquette | 5 | H | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Marsanne | 1 | H | 1 | ||||

| Mavron | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Merlot | 53 | VV | 10 | 36 | 7 | ||

| Montepulciano | 6 | VV | 2 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Moschofilera | 1 | VV | 1 | 1 | |||

| Mourvedre | 3 | VV | 1 | 2 | |||

| Muscadine (unsp.) | 14 | M | 1 | 8 | 4 | 1 | |

| Muscat | 2 | VV | 1 | 1 | |||

| Muscat Canelli | 2 | VV | 2 | ||||

| Muscat Ottonel | 1 | VV | 1 | 1 | |||

| Nebbiolo | 3 | VV | 2 | 1 | |||

| Negroamaro | 2 | VV | 1 | 1 | |||

| Nesbitt | 15 | M | 5 | 7 | 3 | ||

| Niagara | 1 | H | 1 | ||||

| Noble | 37 | M | 12 | 20 | 5 | ||

| Noiret | 2 | H | 2 | ||||

| Norton-Cynthiana | 16 | AN | 1 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 1 |

| Pam | 4 | M | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Paulk | 4 | M | 3 | 1 | |||

| Petit Manseng | 12 | VV | 1 | 8 | 3 | ||

| Petit Pearl | 1 | H | 1 | 1 | |||

| Petit Sirah | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Petit Verdot | 31 | VV | 5 | 20 | 6 | 1 | |

| Pinot Grigio/Gris | 14 | VV | 5 | 7 | 2 | ||

| Pinot Noir | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Pinotage | 1 | VV | 1 | 1 | |||

| Prairie Star | 1 | H | 1 | ||||

| Ravat 34 | 1 | H | 1 | ||||

| Regent | 4 | H | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Ribolla Gialla | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Riesling | 21 | VV | 2 | 8 | 11 | 1 | |

| Rkatsiteli | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Robert S. Lee | 1 | M | 1 | ||||

| Roditis | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Roussanne | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Sagrantino | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Sangiovese | 13 | VV | 4 | 7 | 2 | ||

| Saperavi | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Sauvignon Blanc | 10 | VV | 3 | 5 | 2 | ||

| Scarlet | 3 | M | 3 | ||||

| Scuppernong | 6 | M | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Semillon | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Seyval Blanc | 16 | H | 2 | 3 | 11 | 2 | |

| St. Croix | 2 | H | 1 | 1 | |||

| Soreli | 1 | H | 1 | ||||

| Southern Home | 2 | M | 1 | 1 | |||

| Steuben | 2 | H | 2 | ||||

| Sugargate | 1 | M | 1 | ||||

| Summit | 5 | M | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Sunbelt | 1 | AN | 1 | ||||

| Supreme | 11 | M | 5 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Sweet Jenny | 2 | M | 2 | ||||

| Syrah | 15 | VV | 1 | 5 | 9 | ||

| Tannat | 4 | VV | 1 | 3 | |||

| Tara | 12 | M | 4 | 5 | 3 | ||

| Tempranillo | 3 | VV | 1 | 2 | |||

| Thiakon | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Touriga Nacional | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Traminette | 24 | H | 1 | 4 | 13 | 6 | 4 |

| Triumph | 12 | M | 6 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Valvin Muscat | 1 | H | 1 | ||||

| Vermentino | 4 | VV | 2 | 2 | |||

| Vidal Blanc | 12 | VV | 2 | 1 | 9 | 3 | |

| Villard Noir | 1 | H | 1 | ||||

| Viognier | 23 | VV | 1 | 7 | 12 | 3 | |

| Welder | 1 | M | 1 | ||||

| Xynesteri | 1 | VV | 1 | ||||

| Zinfandel | 4 | VV | 2 | 2 |

Appendix 3: Alphabetical Listing of Cultivars in American Viticultural Areas

Key to Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | ||

|---|---|---|

| AVA Name | Yadkin Valley | YV |

| Swan Creek | SC | |

| Appalachian High Country | AHC | |

| Crest of the Blue Ridge Henderson County | CBRHC | |

| Tryon Foothills (proposed AVA) | TF | |

| Upper Hiwassee Highlands | UHH | |

| Dahlonega Plateau | DP | |

| Haw River | HR | |

| Grape Varieties | Vitis vinifera | VV |

| Hybrid | H | |

| Muscadine | M | |

| American Native | AN |

| Cultivars | Frequency | Variety | YV | SC | AHC | CBRHC | TF | UHH | DP | HR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albariño | 3 | VV | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Arandell | 3 | VV | 3 | 1 | ||||||

| Aromella | 1 | H | 1 | |||||||

| Baco Noir | 1 | H | 1 | |||||||

| Barbera | 3 | VV | 3 | |||||||

| Black Beauty | 1 | M | 1 | |||||||

| Cabernet Franc | 47 | VV | 21 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| Cabernet Sauvignon | 46 | VV | 22 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Carignan | 1 | VV | 1 | |||||||

| Carlos | 4 | M | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Catawba | 6 | H | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||

| Cayuga White | 3 | H | 3 | 1 | ||||||

| Chambourcin | 31 | H | 17 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 2 |

| Chardonel | 9 | H | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Chardonnay | 49 | VV | 26 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 1 |

| Cinsault | 1 | VV | 1 | |||||||

| Concord | 3 | AN | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Corot Noir | 3 | H | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Cowart | 1 | M | 1 | |||||||

| Crimson Cabernet | 1 | H | 1 | |||||||

| Darlene | 1 | M | 1 | |||||||

| Doreen | 1 | M | 1 | |||||||

| Dornfelder | 1 | VV | 1 | |||||||

| Frontenac | 1 | H | 1 | |||||||

| Frontenac Gris | 1 | H | 1 | |||||||

| Fry (unspecified) | 2 | M | 2 | |||||||

| Golden Muscat | 1 | H | 1 | |||||||

| Greco di Tufo | 1 | VV | 1 | |||||||

| Grenache | 4 | VV | 4 | |||||||

| Grüner Veltliner | 6 | VV | 5 | 1 | ||||||

| Ison | 1 | M | 1 | |||||||

| Itasca | 1 | H | 1 | |||||||

| Jumbo | 2 | M | 2 | |||||||

| La Crosse | 1 | H | 1 | |||||||

| Landot Noir | 1 | H | 1 | |||||||

| Lemberger | 2 | VV | 2 | |||||||

| Léon Millot | 1 | VV | 1 | |||||||

| Magnolia | 2 | M | 2 | |||||||

| Malbec | 12 | VV | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Malvasia Bianca | 1 | VV | 1 | |||||||

| Marechal Foch | 4 | H | 4 | |||||||

| Marquette | 3 | H | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Marsanne | 2 | H | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Merlot | 48 | VV | 30 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 1 | |

| Montepulciano | 4 | VV | 4 | 2 | ||||||

| Moschofilera | 1 | VV | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Mourvedre | 4 | VV | 3 | 1 | ||||||

| Muscadine (unspecified) | 5 | M | 3 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Muscat | 3 | VV | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Muscat Canelli | 3 | VV | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Muscat Ottonel | 1 | VV | 1 | |||||||

| Nebbiolo | 3 | VV | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Negroamaro | 1 | VV | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Nesbitt | 1 | M | 1 | |||||||

| Niagara | 1 | H | 1 | |||||||

| Noble | 4 | M | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Noiret | 2 | H | 2 | |||||||

| Norton-Cynthiana | 17 | AN | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | |

| Pam | 1 | M | 1 | |||||||

| Petit Manseng | 12 | VV | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| Petit Pearl | 1 | H | 1 | |||||||

| Petit Sirah | 2 | VV | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Petit Verdot | 27 | VV | 16 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Pinot Blanc | 1 | VV | 1 | |||||||

| Pinot Grigio/Gris | 12 | VV | 8 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Pinot Meunier | 1 | VV | 1 | |||||||

| Pinot Noir | 3 | VV | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Pinotage | 1 | VV | 1 | |||||||

| Ravat 34 | 1 | H | 1 | |||||||

| Regent | 2 | H | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Riesling | 23 | VV | 9 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 4 | |||

| Roussanne | 2 | VV | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Sagrantino | 1 | VV | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Sangiovese | 12 | VV | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Saperavi | 1 | VV | 1 | |||||||

| Sauvignon Blanc | 11 | VV | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Sauvignon Gris | 1 | VV | 1 | |||||||

| Scarlet | 1 | M | 1 | |||||||

| Scuppernong | 1 | M | 1 | |||||||

| Semillon | 1 | VV | 1 | |||||||

| Seyval Blanc | 19 | H | 3 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 1 | ||

| St. Croix | 1 | H | 1 | |||||||

| Steuben | 2 | H | 2 | |||||||

| Sugargate | 1 | M | 1 | |||||||

| Summit | 1 | M | 1 | |||||||

| Supreme | 1 | M | 1 | |||||||

| Sweet Jenny | 2 | M | 2 | |||||||

| Symphony | 1 | VV | 1 | |||||||

| Syrah | 14 | VV | 12 | 2 | ||||||

| Tannat | 6 | VV | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Tara | 1 | M | 1 | |||||||

| Tempranillo | 2 | VV | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Teroldego | 1 | VV | 1 | |||||||

| Touriga Nacional | 6 | VV | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||||

| Traminette | 24 | H | 11 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Valvin Muscat | 1 | H | 1 | |||||||

| Vermentino | 3 | VV | 3 | 2 | ||||||

| Vidal Blanc | 14 | VV | 2 | 6 | 4 | 2 | ||||

| Villard Noir | 2 | H | 2 | |||||||

| Viognier | 22 | VV | 15 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Zinfandel | 4 | VV | 2 | 1 | 1 |

Appendix 4: Listing of cultivars by Frequency of Planting in Northern Tier of AVAs

| Region | Cultivars | Plantings |

|---|---|---|

| Appalachian High Country Blue Ridge Plateau | Seyval Blanc | 6 |

| Traminette | 4 | |

| Marechal Foch | 4 | |

| Cab. Sauvignon | 2 | |

| Vidal Blanc | 2 | |

| Catawba | 2 | |

| Concord | 2 | |

| Marquette | 2 | |

| Noiret | 2 | |

| Steuben | 2 | |

| Chardonnay | 1 | |

| Perit Verdot | 1 | |

| Cab. Franc | 1 | |

| Chambourcin | 1 | |

| Riesling | 1 | |

| Pinot Grigio/Gris | 1 | |

| Sangiovese | 1 | |

| Norton-Cynthiana | 1 | |

| Corot Noir | 1 | |

| Pinot Noir | 1 | |

| Frontenac | 1 | |

| Frontenac Gris | 1 | |

| Golden Muscat | 1 | |

| Itasca | 1 | |

| La Crosse | 1 | |

| Landot Noir | 1 | |

| Petit Pearl | 1 | |

| St. Croix | 1 | |

| Yadkin Valley Western Piedmont | Merlot | 25 |

| Chardonnay | 22 | |

| Cab. Sauvignon | 22 | |

| Cab. Franc | 21 | |

| Chambourcin | 17 | |

| Petit Verdot | 16 | |

| Traminette | 11 | |

| Viognier | 11 | |

| Syrah | 9 | |

| Riesling | 7 | |

| Sangiovese | 6 | |

| Norton-Cynthiana | 5 | |

| Petit Manseng | 5 | |

| Pinot Grigio/Gris | 5 | |

| Arandeil | 4 | |

| Barbera | 4 | |

| Malbec | 4 | |

| Cayuga White | 3 | |

| Grenache | 3 | |

| Montepulciano | 3 | |

| Mourvedre | 3 | |

| Sauvignon Blanc | 3 | |

| Seyval Blanc | 3 | |

| Carlos | 2 | |

| Corot Noir | 2 | |

| Muscat Canelli | 2 | |

| Noble | 2 | |

| Tannat | 2 | |

| Tempranillo | 2 | |

| Vermentino | 2 | |

| Zinfandel | 2 | |

| Albarifio | 1 | |

| Carignan | 1 | |

| Chardonel | 1 | |

| Cinsault | 1 | |

| Doreen | 1 | |

| Marsanne | 1 | |

| Moschofilera | 1 | |

| Nebbiolo | 1 | |

| Negroamaro | 1 | |

| Niagara | 1 | |

| Sagrantino | 1 | |

| Semillon | 1 | |

| Touriga Nacional | 1 | |

| Valvin Muscat | 1 | |

| Swan Creek Western Piedmont | Merlot | 6 |

| Chardonnay | 5 | |

| Petit Verdot | 4 | |

| Cab. Sauvignon | 3 | |

| Cab. Franc | 3 | |

| Chambourcin | 3 | |

| Riesling | 3 | |

| Pinot Grigio/Gris | 3 | |

| Viognier | 2 | |

| Traminette | 2 | |

| Sangiovese | 2 | |

| Montepulciano | 2 | |

| Sereval Blanc | 2 | |

| Vermentino | 2 | |

| Norton-Cynthiana | 1 | |

| Petit Manscng | 1 | |

| Sauvignon Blanc | 1 | |

| Arandell | 1 | |

| Cayua White | 1 | |

| Muscat Canelli | 1 | |

| Corot Noir | 1 | |

| Tempranillo | 1 | |

| Moschofilera | 1 | |

| Negroamaro | 1 | |

| Sagrantino | 1 | |

| Yadkin Valley Eastern Piedmont | Merlot | 5 |

| Cab. Sauvignon | 4 | |

| Chardonnay | 4 | |

| Viognier | 4 | |

| Muscadine (unsp) | 3 | |

| Petit Verdot | 3 | |

| Pinot Grigio/Gris | 3 | |

| Syrah | 3 | |

| Cab. Franc | 2 | |

| Chambourcin | 2 | |

| Grenache | 2 | |

| Malbec | 2 | |

| Riesling | 2 | |

| Sauvignon Blanc | 2 | |

| Montepulciano | 1 | |

| Mourvedre | 1 | |

| Muscat | 1 | |

| Petit Syrah | 1 | |

| Roussanne | 1 | |

| Sangiovese | 1 | |

| Vermentlno | 1 | |

| Haw River Eastern Piedmont | Cab. Sauvignon | 2 |

| Cab. Franc | 2 | |

| Chambourcin | 2 | |

| Chardonel | 2 | |

| Traminette | 2 | |

| Chardonel | 2 | |

| Noble | 2 | |

| Fry (unspec) | 2 | |

| Jumbo | 2 | |

| Magnolia | 2 | |

| Sweet Jenny | 2 | |

| Chardonnay | 1 | |

| Merlot | 1 | |

| Norton-Cynthiana | 1 | |

| Petit Manseng | 1 | |

| Sangiovese | 1 | |

| Tannat | 1 | |

| Seyval Blanc | 1 | |

| Nebbiolo | 1 | |

| Black Beauty | 1 | |

| Cowart | 1 | |

| Chrimson Cabernet | 1 | |

| Darlene | 1 | |

| Ison | 1 | |

| Nesbitt | 1 | |

| Pam | 1 | |

| Scarlet | 1 | |

| Scuppernong | 1 | |

| Sugargate | 1 | |

| Summit | 1 | |

| Supreme | 1 | |

| Tara | 1 |

Appendix 5: Listing of Cultivars by Frequency of Planting in Central and Southern Tiers of AVAs

| Region | Cultivars | Plantings |

|---|---|---|

| Crest of the Blue Ridge HC Ridge Plateau | Cab. Franc | 8 |

| Merlot | 6 | |

| Cab. Sauvignon | 5 | |

| Vidal Blanc | 6 | |

| Riesling | 6 | |

| Chardonnay | 5 | |

| Petit Verdot | 4 | |

| Gruner Veltliner | 4 | |

| Traminette | 3 | |

| Norton-Cynthiana | 2 | |

| Sauvignon Blanc | 2 | |

| Lemberger | 2 | |

| Catawba | 1 | |

| Chambourcin | 1 | |

| Petit Manseng | 1 | |

| Malbec | 1 | |

| Zinfandel | 1 | |

| Chardonel | 1 | |

| Regent | 1 | |

| Baco Noir | 1 | |

| Dornfelder | 1 | |

| Leon Millot | 1 | |

| Malvasia Bianca | 1 | |

| Muscat Ottonel | 1 | |

| Pinotage | 1 | |

| Saperavi | 1 | |

| Tryon Foothills Western Piedmont | Merlot | 5 |

| Cab. Sauvignon | 5 | |

| Cab. Franc | 3 | |

| Chardonnay | 3 | |

| Petit Verdot | 3 | |

| Sauvignon Blanc | 2 | |

| Petit Manseng | 2 | |

| Malbec | 2 | |

| Chambourcin | 1 | |

| Viognier | 1 | |

| Pinot Grigio/Gris | 1 | |

| Muscadine | 1 | |

| Tannat | 1 | |

| Muscat | 1 | |

| Upper Hiwassee Highlands Blue Ridge Plateau | Seyval Blanc | 8 |

| Chambourcin | 7 | |

| Cab. Franc | 6 | |

| Norton-Cynthiana | 5 | |

| Vidal Blanc | 4 | |

| Riesling | 4 | |

| Chardonel | 4 | |

| Cab. Sauvignon | 3 | |

| Chardonnay | 3 | |

| Cataw•ta | 3 | |

| Pinot Grigio/Gris | 2 | |

| Traminette | 2 | |

| Villard Noir | 2 | |

| Merlot | 1 | |

| Petit Verdot | 1 | |

| Petit Manseng | 1 | |

| Viognier | 1 | |

| Muscadine (unsp) | 1 | |

| Gruner Veltliner | 1 | |

| Zinfandel | 1 | |

| Regent | 1 | |

| Marquette | 1 | |

| Sangiovese | 1 | |

| Touriga Nacional | 1 | |

| Albarino | 1 | |

| Aromella | 1 | |

| Ravat 34 | 1 | |

| Symphony | 1 | |

| Dahlonega Plateau Western Piedmont | Chardonnay | 5 |

| Merlot | 5 | |

| Cab. Sauvignon | 4 | |

| Viognier | 4 | |

| Touriga Nacional | 4 | |

| Cab. Franc | 3 | |

| Norton-Cynthiana | 3 | |

| Malbec | 3 | |

| Chambourcin | 2 | |

| Vidal Blanc | 2 | |

| Petit Verdot | 2 | |

| Petit Manseng | 2 | |

| Sangiovese | 2 | |

| Sauvignon Blanc | 2 | |

| Tannat | 2 | |

| Pinot Noir | 2 | |

| Syrah | 2 | |

| Seyval Blanc | 1 | |

| Chardonel | 1 | |

| Albarino | 1 | |

| Muscat Canelli | 1 | |

| Mourvedre | 1 | |

| Marsanne | 1 | |

| Nebbiolo | 1 | |

| Petit Sirah | 1 | |

| Roussanne | 1 | |

| Greco di Tufo | 1 | |

| Pinot Blanc | 1 | |

| Sauvignon Gris | 1 | |

| Teroldego | 1 |

References

Carter, L., A. Terando, K. Dow, K. Hiers, K. E. Kunkel, A. Lascurain, D. Marcy, M. Osland, and P. Schramm. 2018. "Southeast." In Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II, by D. R. Reidmiller, C. W. Avery, D. R. Easterling, K. E. Kunkel, K. L. M. Lewis, T. K. Maycock and B. C. Stewart, 743–808. Washington, DC: U.S. Global Change Research Program. doi: 10.7930/NCA4.2018.CH19 ↲

Hall, A., and G. V. Jones. 2010. "Spatial analysis of climate in wine-growing regions of Australia." Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. Do:10.1111/j.1755-0238.2010.00100.x ↲

Jones, Gregory. 2015. "Climate, Grapes, and Wine: Terroir and the Importance of Climate to Winegrape Production." Guildsomm. August 12. Accessed June 17, 2024. ↲

Jones, Gregory V, Andrew A. Duff, Andrew Hall, and Joseph W. Myers. 2010. "Spatial Analysis of Climate in Winegrape Growing Regions in the Western United States." American Journal of Enology and Viticulture (61): 313–326. ↲

Jordan, T. D., R. M. Pool, T. J. Zabadal, and J. P. Tomkins. 1980. Cultural Practices for Commercial Vineyards. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Cooperative Extension. ↲

Poling, Barclay, and Sara Spayd. 2015. The North Carolina Winegrape Grower’s Guide. Raleigh, NC: NC State Extension. ↲

U.S. Geological Survey. 2018. USGS EROS Archive - Aerial Photography - National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP). July 6. Accessed June 17, 2024. ↲

WineBusiness Analytics. 2024. U.S. Wineries - Annual Production (Cases) 2023 Production (prelim). Accessed June 17, 2024. ↲

Wolf, Tony Kenneth, Alson H. Smith, and Gill Giese. 2020. Floor Management Strategies for Virginia Vineyards. Blacksburg, VA: Virginia Cooperative Extension. ↲

Publication date: July 23, 2024

AG-966

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.