Wildlife benefit landowners in many ways. Some people enjoy hunting deer, rabbits, turkey, and bobwhite quail on their property. Others simply enjoy watching or photographing these and other animals.

When it comes to attracting wildlife, the owners of pine plantations have a special challenge. Without proper management, most plantations lose much of their plant and animal diversity as they age and the tree crowns shade understory vegetation.

However, appropriate management can be used to improve pine plantations as habitat for a variety of wildlife species. This publication details strategies that can provide habitat for many wildlife species without significantly reducing timber production or cash flow.

Develop a Management Plan

Before beginning wildlife habitat improvement, develop a management plan. This helps define the steps needed to ensure that your original land management objectives are met. The plan should include maps and descriptions that provide a record of the original status of a property and enable assisting professionals to target areas for improvement.

Because each action taken to manage a pine plantation has an associated effect on the stand’s potential to attract wildlife and produce forest products, you should answer certain questions and specify objectives before creating a management plan. Each property is unique and requires specific recommendations. A registered forester or professional wildlife biologist can help find the right combination for you and your property. Below are some important questions to answer.

Where does wildlife management rank in your list of objectives?

If you rank timber production above wildlife management, then you must consider the loss of timber production resulting from wildlife management. For example, creating planted food plots or disked openings within a pine plantation may enhance the value of the stand for white-tailed deer, wild turkeys, and cottontail rabbits; however, these openings are made and maintained at the expense of pine trees and future timber production.

How complete is your property as a wildlife resource?

North Carolina landowners should be aware of the limitations and shortcomings of their properties. For example, some properties contain poor soils that may limit efforts to attract some wildlife. On small properties adjacent to metropolitan areas, management of pine plantations for some wildlife, such as northern bobwhite quail and wild turkey, may be difficult because the surrounding properties are not hospitable to these focal wildlife species. As another example, pine plantations on converted agricultural lands contain fewer understory plant species than plantations on previously forested sites and may require remedial measures to provide sufficient food and shelter for wildlife.

Which wildlife species are you targeting?

No pine plantation, or any other forest type, can provide quality habitat for all wildlife species. Therefore, you mustidentify focal wildlife species before management recommendations can be made. For example, burning under a moderate canopy cover (that is, greater than 70% overstory cover) will benefit white-tailed deer by promoting browse. However, bobwhite quail will not thrive under this scenario because the species requires much lower tree cover (less than 40% canopy cover).

How much will this cost?

Management for wildlife is not free. Disking openings, prescribed burning, and applying herbicides cost money. Although these activities may improve timber production, their costs typically will not be justifiable for timber production alone. Consultation with a professional and planning, however, will help minimize these costs.

Plant Variety and Structure

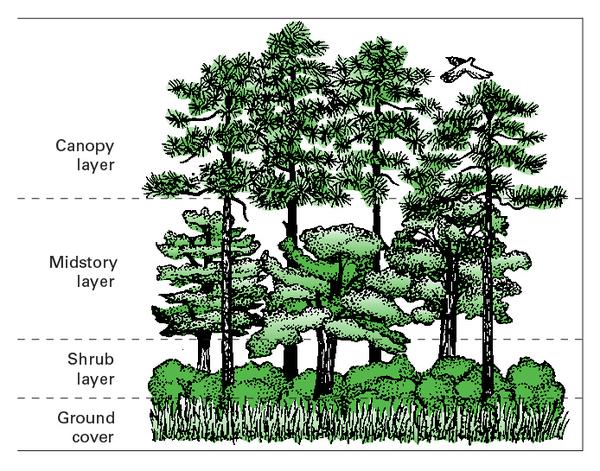

Densely stocked pine plantations generally lack the plant variety and structure of pine stands managed with frequent thinning and prescribed burning. Thinning and burning increase understory structure, thereby providing food and cover for a large number of wildlife species. Extensive understory characterized by a variety of plant species will provide a variety of wildlife foods that are available throughout the year. Having plants in all vertical layers, including the understory, allows ground-, shrub-, and treetop-dwelling wildlife to exist in the same horizontal space (Figure 1). Having different stand ages on a property provides alternative food and cover sources at a larger scale. Grasses, forbs, shrubs, and vines growing on or near the ground (that is, the understory) are especially important because many animals are confined to the forest floor. Low-growing plants provide fruits and seeds as food, cover for nesting and escape from predators, and leaves for browsing. Taller, older trees provide nesting sites for treetop songbirds and produce seeds and fruits eaten by many animals.

Site Preparation and Early Management

A large number of wildlife species use young pine plantations. Young pine plantations provide dense protective cover low to the ground where most wildlife live. Wildlife-friendly stands of this age are rich with fruiting plants, such as blackberry, and provide abundant browse for white-tailed deer and cottontail rabbits. To increase plant variety, structure, and food in young pine plantations, use these management strategies:

- Do not prepare the site as intensively, leaving some non-pine plant species (for example, blackberry, pokeweed, some hardwood sprouts).

- Leave woody debris (such as, logging residue from the harvest) on the ground or in piles to provide cover and food for a variety of wildlife species (Figure 2).

- Reduce control of non-pine plants during early-growth periods by applying herbicides only along the planted rows of trees (called banded application) and not in the areas between rows as is the case with a broadcast application.

- Plant pines at wider spacing, usually at least 10 feet by 10 feet apart or wide enough to accommodate management activities like disking in rows. If bedding, use wider bed spacing, leaving non-pine vegetation between beds.

- On appropriate sites, plant longleaf pine because its grass stage and sparse crown allow an extended period of understory presence before crown closure. Longleaf pine also tolerates burning better and earlier than other pine species. Shortleaf pine is another option for establishing in a plantation.

- Plan for prescribed burns by installing and maintaining wide firebreaks around the plantation.

Mid-Rotation Management

As densely stocked plantations mature and the canopy closes, shaded understory vegetation dies, food production decreases, cover is reduced, and overall habitat quality declines (Figure 3). That is why many people use the phrase “biological desert” to describe mid-rotation pine stands. At this stage, management activities that increase sunlight in the forest understory benefit wildlife the most (Figure 4). Increased sunlight on the forest floor promotes herbaceous plant and shrub growth, which provides food and cover beneficial to animals, such as songbirds, white-tailed deer, wild turkey, northern bobwhite quail, and cottontail rabbits. Before the canopy of a plantation closes and the stand becomes overstocked:

- Thin early and often. Consider pre-commercial thinning early in the stand rotation before trees have merchantable value. Cost-share programs can help offset the costs of this practice.

- Conduct commercial thinning to allow sunlight to penetrate the canopy (thin to canopy cover of 50% to 70%, or lower if managing for bobwhite quail).

- Do not remove better-formed oaks during thinning because they provide acorns and withstand light understory burning.

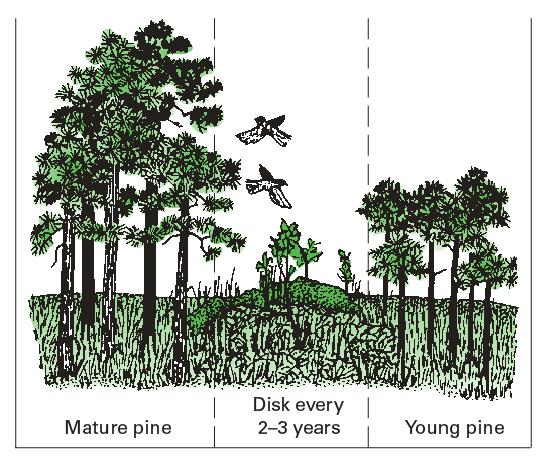

- Create openings of 1 to 5 acres and disk or burn the openings once every two to three years in pine plantations larger than 50 acres.

- If heavy thinning of the entire stand is not an option, thin more heavily in areas adjacent to wildlife openings and along stand boundaries to maximize wildlife food and cover.

- Prescribe burn every two to five years once planted pines are 15 feet tall (earlier for longleaf pines), or burn every two to three years if you favor bobwhite quail. The appropriate fire return interval depends on the focal species, soil type, and several other factors unique to each property.

- Disk firebreaks every two to three years or plant firebreaks as food plots.

- Apply herbicides and prescribe burn after mid-rotation thinning to remove undesirable hardwoods like sweetgum and red maple and promote herbaceous ground cover.

Late-Rotation Management

Unthinned plantations can become too dense to allow understory development or persistence. In older pine stands, if understory vegetation becomes sparse, food and cover is absent for many wildlife. Take the following steps to attract wildlife:

- Continue thinning to allow sunlight to reach the forest floor (thin to 50% to 70% canopy cover or lower if managing for bobwhite quail).

- If thinning to low overstory cover conflicts with timber management objectives, limit heavier thinning to the first 50 to 100 feet from the edges of haul roads, wildlife openings, and stand boundaries.

- Continue burning every two to five years, making sure to intersperse the stands that are burned in any year.

- Fire increases production of fruit by shrubs and vines beginning two years after the burn and ending about five years after the burn.

- Fire makes leafy browse more nutritious for one to two months after the burn.

- Fire promotes growth of legumes and other forbs and grasses favored by wildlife.

- Fire prevents hardwood midstory encroachment and maintains vegetation structure in the understory.

- Where safe, leave dead trees (called snags) for cavity-nesting birds and squirrels.

- Maintain 1- to 5-acre openings within stands, which can be disked or burned to maintain in early succession or planted as food plots.

- Daylight management roads by removing adjacent trees, creating a wider area for sunlight to enter adjacent plantations and to facilitate drying of roads after precipitation.

Harvest Techniques

The final harvest gives you the opportunity to make improvements for wildlife in the next rotation. Consider these harvest strategies:

- Leave residual snags or large-diameter live stems as wildlife trees for the next rotation.

- Leave hollow and non-commercial logs, treetops, and logging debris on site after harvesting. As remnant logs and slash decay, they promote growth of fungi, which are an important phosphorus source for white-tailed deer; attract insects, which serve as food for other wildlife; provide cover for small mammals, salamanders, and snakes; and help protect soil quality.

- Leave unharvested areas along streams and in low-lying areas to maintain acorn and fleshy fruit production and to provide travel corridors for mature woodland species like wild turkeys and gray squirrels.

- Use seed tree or shelterwood regeneration harvests, which leave some mature trees in the overstory to be harvested several years after the initial harvest or during the late stages of the next rotation.

- Limit most clearcuts to less than 50 acres and disperse harvest units across the landscape to maximize stand age diversity.

Landscape Considerations

In the past, wildlife biologists and foresters made management recommendations one stand at a time. However, the distribution of certain wildlife species is affected by the arrangement (interspersion) of stand types and ages on the surrounding land. Some animals need more than one type of vegetation community or stand age to survive. For example, mature forest without young forest openings or fallow fields nearby may not attract turkeys because the birds need both mature forest stands and early succession plant communities when raising young. Understanding the relationship between your target species and the surrounding landscape will help improve the effectiveness of your wildlife habitat improvements.

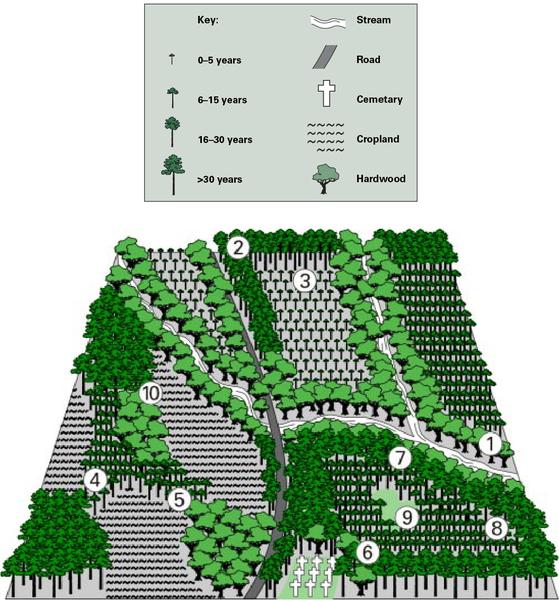

To determine the composition of the surrounding lands, review aerial photographs or a U.S. Geological Survey quadrangle map. The best option is to develop a partnership with neighboring property owners. As partners, the group could set goals and plan how to provide the greatest benefit to wildlife across a large land area. For example, each landowner could plan to create a unique vegetation type (such as a duck impoundment, fallow field, or oak stand). Landscape management requires planning and consideration of the following strategies (Figure 5):

- Consider your property as a part of the larger surrounding landscape when developing a wildlife management plan.

- Mix stands of different ages and forest types.

- Maintain unharvested buffers that are more than 100 feet wide on each side of streams as habitat and travel corridors for wildlife associated with riparian forest, and plant pines to link forest stands isolated by development or agriculture.

- Use longer rotations when focal wildlife are associated with mature forest.

- Minimize timber management on special sites like home sites, cemeteries, or historical areas.

- Leave unharvested strips of trees that are at least 50 feet wide along roads to screen the view of timber harvests, or harvest these zones 5 to 10 years after the initial harvest.

Figure 5 Landscape Considerations

- Leave hardwoods standing along ditches, streams, and rivers.

- Leave a 50-foot forested buffer adjacent to roads to help screen the view of harvesting.

- Limit clearcuts to less than 50 acres.

- Plant pines to link older, isolated pine stands.

- Plant pines to link isolated stands of hardwood.

- Leave mature stands around special sites like cemeteries.

- Manage pines adjacent to streamside buffers on longer rotations.

- Intersperse pines of different ages as much as possible.

- Maintain irregularly shaped, 1- to 5-acre herbaceous openings within plantations.

- Maximize the areas where multiple vegetation types meet.

Should Edges Be Managed Differently?

Edges usually are home for a greater variety and number of plants and animals than interior areas, often because the interior areas are closed canopy and lack complex vertical structure. Edges may have dense plant growth when adjacent to openings that allow sunlight penetration, and animals spending time along stand edges have simultaneous access to two land cover types. Ideally, an entire forest stand should be thinned and burned so the entire area contains complex vertical structure important to a variety of wildlife. However, if thinning heavily is not an option, consider limiting heavy thins to the boundaries of forest stands. Consider the following related to edges:

- Manage the boundaries between a plantation and an adjacent field or forest stand by disking every two to three years or by planting food plots (Figure 6).

- Maintain firebreaks and roads within and along the edge of plantations in early succession by disking in late winter or by planting as food plots.

- Time harvests to maximize the age difference between adjacent stands. The greater the difference in age between adjacent stands (edge contrast), the greater the diversity and abundance of wildlife likely to be present in that local area.

Fertilization and Herbicides

Increasing demands for forest products and rising land prices have forced many North Carolina landowners to grow trees more efficiently. Two methods that improve growth in pine plantations are fertilization and herbicide use. Herbicides, which control vegetation, are tested extensively before being registered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and are relatively nontoxic to wildlife when used according to label directions. Applying single herbicides at very high rates or applying tank mixes of several different herbicides normally kills most non-pine plants, reducing plant diversity and structure for a period of time. The most obvious visual impacts on wildlife habitat generally last for only one year after herbicide treatment. Though fertilization may be used to help pines grow faster, the practice is not recommended to improve wildlife habitat because it is expensive and any benefits are short lived. If fertilizing, too much nitrogen may prohibit legume germination. Also, fertilizing under a closed canopy will have few effects on understory plants, so fertilize early in the rotation or after thinning to maximize the benefits to understory plants browsed upon by deer and rabbits. When applying herbicides, consider the following recommendations.

Herbicides

- To prevent total control of competing vegetation, avoid herbicide tank mixtures that kill all non- pine plant species (Table 1).

- Use herbicides that do not injure or kill preferred wildlife plants like legumes and blackberry.

- Use herbicide release treatments as soon after planting as possible because many wildlife species depend on the plant variety and structure that develop before crown closure.

- Hand apply herbicides around individual trees or use band or spot application techniques.

- Make aerial herbicide applications in combination with prescribed fire after thinnings to kill midstory hardwoods and to increase forest floor herbs, grasses, and shrubs valuable to wildlife.

- Do not apply herbicides to low-lying hardwoods, ditches and streambeds, or standing water within or adjacent to plantations.

| Active Ingredient | Soil Activity [+] | Product Name and Application Rate/Acre | Tolerant Non- Pine Species | Labeled Tank Mixes [*] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imazapyr |

Medium (10 days half-life) |

Arsenal (12–24 oz) Chopper (24–48 oz) |

Legumes, blackberry, redbud, wax myrtle, buckeye, and elm | Glyphosate, Triclopyr, Metsulfuron methyl, Sulfometuron methyl |

| Hexazinone |

High (90 days half-life) |

Pronone (10–40 lb) Velpar (1–3 gal) |

Some grasses and woody vines, poplar, hollies, blackgum, sassafras, Eastern redcedar, and American beautyberry | Glyphosate, Picloram, Imazapyr, Triclopyr, Metsulfuron methyl, Sulfometuron methyl |

| Sulfometruon methyl |

High (20–28 days half-life) |

Oust (2–6 oz) | Some grasses and woody vines | Glyphosate, Imazapyr, Hexazinone Atrazine |

| Triclopyr |

Low (8–279 days half-life) |

Garlon (1–8 qts) | Grasses, black cherry, Eastern redcedar | Glyphosate, Imazapyr, Picloram, Hexazinone |

| Metsulfuron methyl |

High (30 days half-life) |

Escort (0.5–2 oz) | Most hardwoods | Glyphosate, Imazapyr, Hexazinone |

| Glyphosate | None (average 47 days half-life) | Accord (2–5 qts) | Woody vines, black cherry, hickory, and dogwood | Metsulfuron methyl, Triclopyr, Imazapyr |

[*] Commonly recommended tank mixes used to control the tolerant non-pine species. ↲

[+] Soil activity is the ability of plants to absorb the herbicide from soil. The half-life of an herbicide is the time it takes for half the herbicide to be removed from the soil. After five half-lives, 97% of the herbicide is removed from the soil. ↲

Several three-herbicide combinations are also approved for use.

Conclusion

Management of pine plantations for both profit and wildlife habitat requires substantial planning and investment. However, these efforts can be surprisingly successful and rewarding. Left unattended, pine plantations become extremely poor wildlife habitat after crown closure. Management techniques that increase the abundance and diversity of plants, especially in the understory, benefit wildlife (for example, thinning and burning). Ask a professional forester or wildlife biologist to help you develop a management plan and to improve wildlife habitat in your pine plantations. The financial costs associated with improving wildlife habitat in plantations may be partially or fully covered by state and federal cost-share programs. For more information, contact the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, the North Carolina Forest Service, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the local Cooperative Extension agent in your county, or a consulting forester.

Additional Resources

Thinning Pine Stands, WON-13

Site Preparation Methods and Contracts, WON-15

Steps to Successful Pine Planting, WON-16

Enrolling in North Carolina's Forest Stewardship Program, WON-23

Wildlife and Forest Stewardship, WON-27

Management by Objectives: Successful Forest Planning, WON-32

Accomplishing Forest Stewardship with Hand-Applied Herbicides, AG-530

Using Fire to Improve Wildlife Habitat, AG-630

Publication date: April 2, 2024

WON-38

Recommendations for the use of agricultural chemicals are included in this publication as a convenience to the reader. The use of brand names and any mention or listing of commercial products or services in this publication does not imply endorsement by NC State University or N.C. A&T State University nor discrimination against similar products or services not mentioned. Individuals who use agricultural chemicals are responsible for ensuring that the intended use complies with current regulations and conforms to the product label. Be sure to obtain current information about usage regulations and examine a current product label before applying any chemical. For assistance, contact your local N.C. Cooperative Extension county center.

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.