Irish potatoes are attacked by most of the insects that infest closely related solanaceous plants like tomato, eggplant, and pepper. Because potatoes are grown for their edible tubers, they must receive greater protection from soil-inhabiting pests. Wireworms, tuberworms, white grubs, and vegetable weevils are pests that growers should monitor stringently.

A. Pests that feed externally on the upper plant

- Chewing pests that make holes in leaves

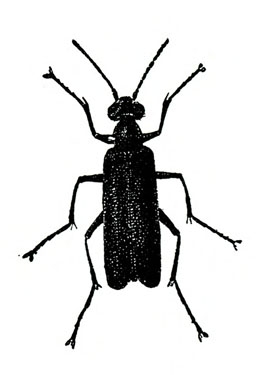

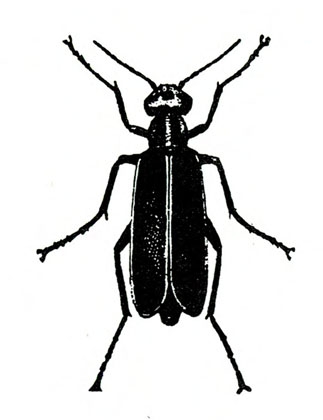

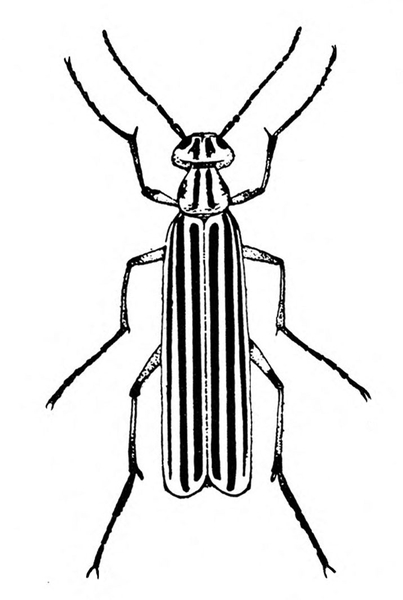

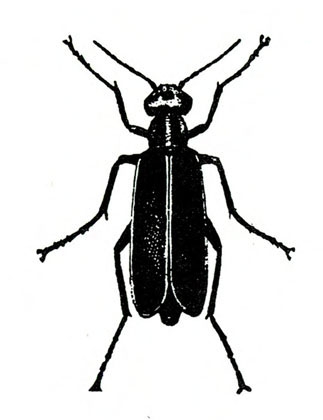

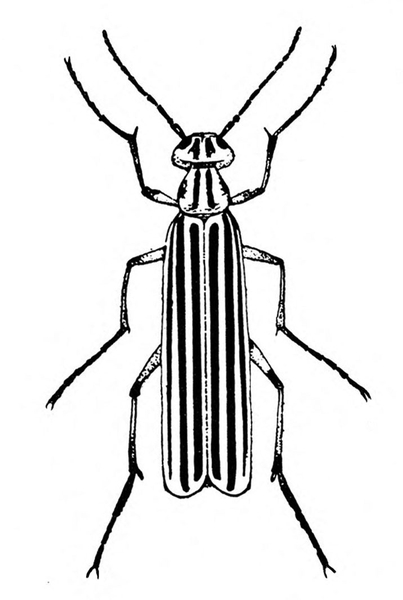

- Blister beetles—These are multiple species of slender, elongate beetles up to 3/4 inch long with prominent heads. Bodies are variously colored but usually are black (Figure 1A), black with yellow margins (Figure 1B), or black-and-yellow striped (Figure 1C). Signs of heavy infestation include stringy, black excrement on plants and ragged foliage. Plants are sometimes stunted.

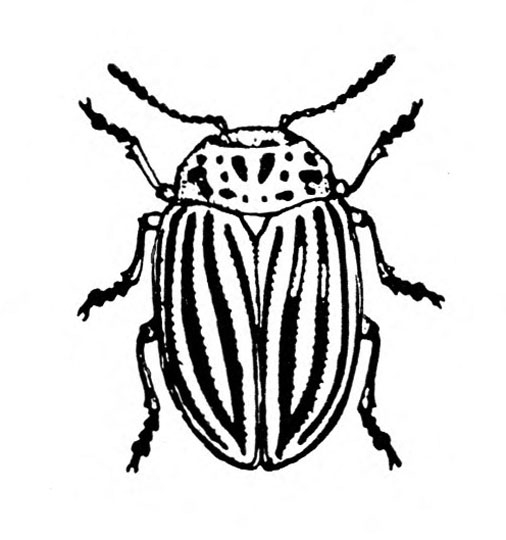

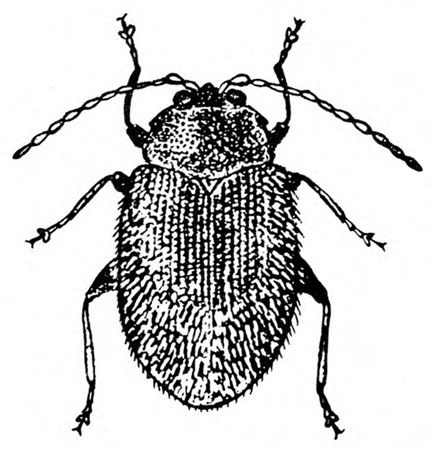

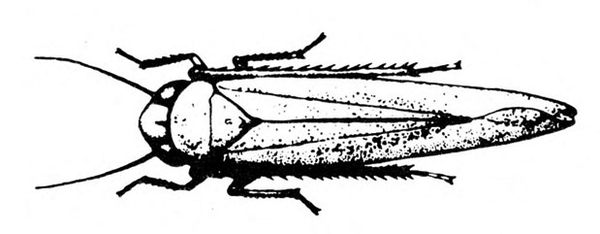

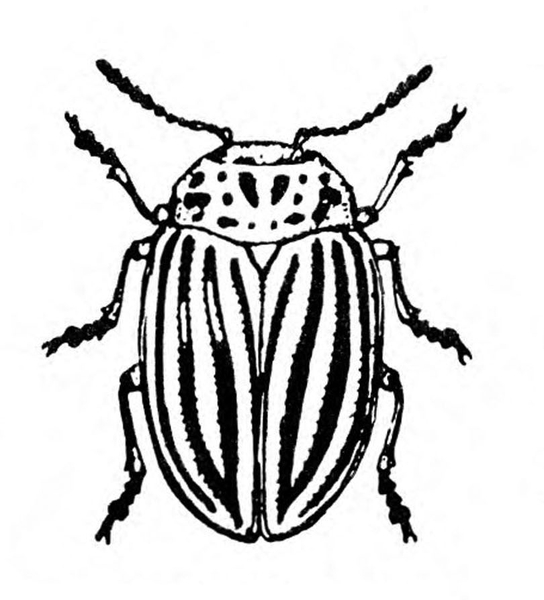

- Colorado potato beetle—This yellowish-brown, oval beetle (Figure 2) may grow up to 9/16 inch long, with five longitudinal black stripes on each wing cover and several black spots on the pronotum (area behind the head). It feeds on leaves and terminal growth.

- Flea beetles—These are various species of tiny, dark-colored beetles that are 1/16 to 3/16 inch long. They have a solid-colored or dark body with a pale-yellow stripe on each wing cover (Figure 3). They chew tiny, round holes in foliage.

- Sap-sucking pests that cause discoloration, deformation, or abscission (shedding of plants parts)

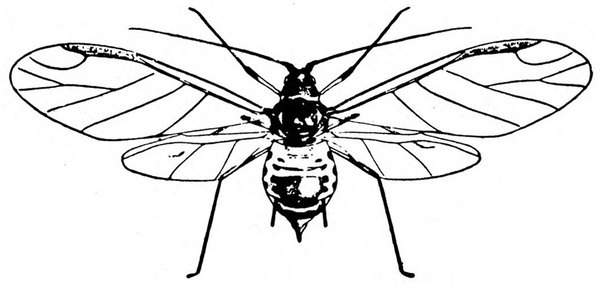

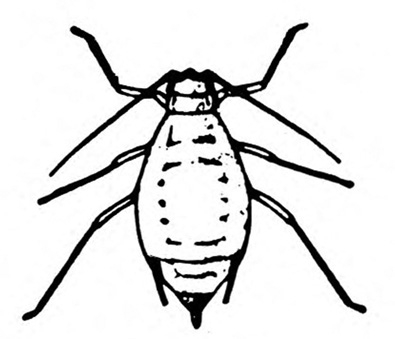

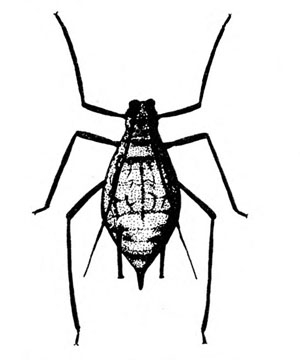

- Aphids—These pale-green to dark-green, soft-bodied, pear-shaped insects have a pair of dark cornicles and a short "tail" (the cauda) protruding from the abdomen. The body is 1/16 to almost 3/16 inch long. They may be winged or wingless, though the wingless form is most common. Aphids feed in colonies. They cause discoloration or mottling of foliage, often transmit viruses, and excrete honeydew on which sooty mold grows.

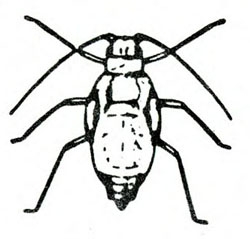

- Green peach aphid—The pale-yellow to green, wingless adult (Figure 4B) is almost 1/8 inch long. The winged adult (Figure 4A) has a dark, dorsal blotch on its yellowish-green abdomen. The cornicles are more than twice as long as the cauda. Nymphs may have three dark lines on the abdomen (Figure 4C). (For more information about green peach aphids, see “Pests of Lettuce.”)

- Potato aphid—Both the adult and nymph may be solid pink, mottled green-and-pink, or light green with a dark stripe. The adult is a little more than 1/8 inch long, with long, slender cornicles about twice as long as the cauda (Figure 5). (For more information about potato aphids, see “Pests of Lettuce.”)

- Potato leafhopper—A spindle-shaped pest up to 1/8 inch long, it has a green body with yellowish to dark-green spots (Figure 6). It usually jumps instead of flies. It extracts sap from undersides of leaves, causing them to crinkle and curl upward. It also causes yellowing of leaf tips and margins known as "hopperburn."

- Aphids—These pale-green to dark-green, soft-bodied, pear-shaped insects have a pair of dark cornicles and a short "tail" (the cauda) protruding from the abdomen. The body is 1/16 to almost 3/16 inch long. They may be winged or wingless, though the wingless form is most common. Aphids feed in colonies. They cause discoloration or mottling of foliage, often transmit viruses, and excrete honeydew on which sooty mold grows.

B. Pests that feed on underground plant parts, bore into stems, or mine into leaves and petioles

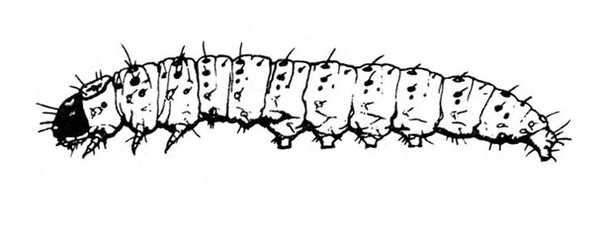

- European corn borer—This cream-colored to light-pink caterpillar has a reddish-brown to black head and a body up to 1 inch long with several rows of dark spots. It has three pairs of legs near the head and five pairs of prolegs (Figure 7). It bores into stems, leaving tangled frass and silk that the borer produces near the entrance hole. Stems may break, or plants may yellow or wilt readily. (For more information about European corn borers, see “Pests of Sweet Corn.”)

- Potato tuberworm—Young caterpillars are creamy white, while mature ones are green to pink. This caterpillar grows up to 3/4 inch long and has a dark-brown head, three pairs of legs near the head, and five pairs of prolegs (Figure 8). It mines in older lower leaves, causing grayish, papery blotches. It tunnels in tubers that are exposed or close to the soil surface, filling tunnels with excrement. Entrance holes are usually near the potato eyes and surrounded by a pink coloration.

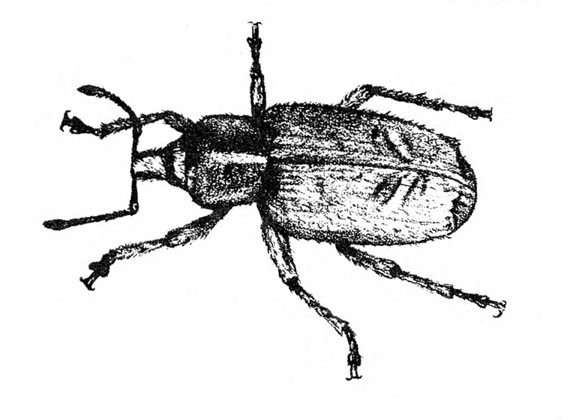

- Vegetable weevil and larva—The adult weevil is dull grayish-brown, about 1/4 inch long, with a short, stout snout and light V-shaped mark on the wing covers (Figure 9A). The larva is pale green, up to 3/8 inch long, and legless, with a dark, mottled head (Figure 9B). Both adults and larvae feed at night, making large, open holes on the surface of potatoes. They feed primarily on underground plant parts but sometimes consume buds and foliage. (For more information about vegetable weevils, see “Pests of Crucifers.”)

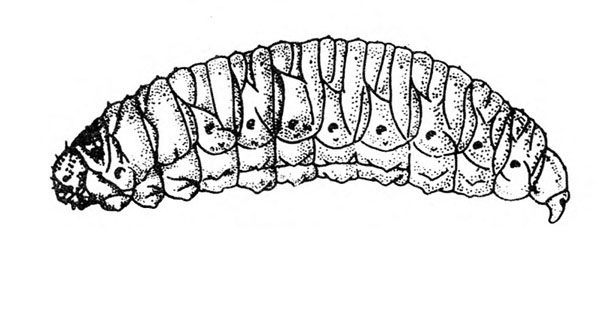

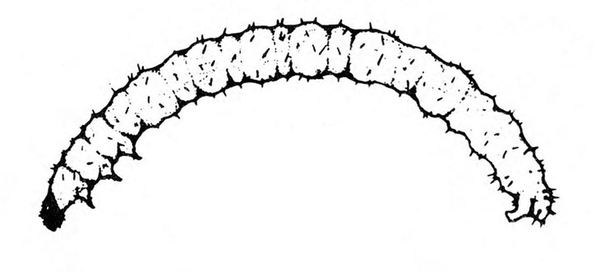

- White grubs—Several species of creamy-white grubs have a distinct brown head capsule, three pairs of legs near the head, and a slightly enlarged abdomen. The bodies are C-shaped and up to 2 inches long (Figure 10). These pests sever roots and stems of potatoes and leave large, shallow, circular holes in tubers.

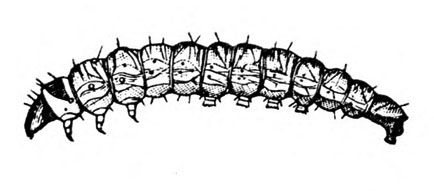

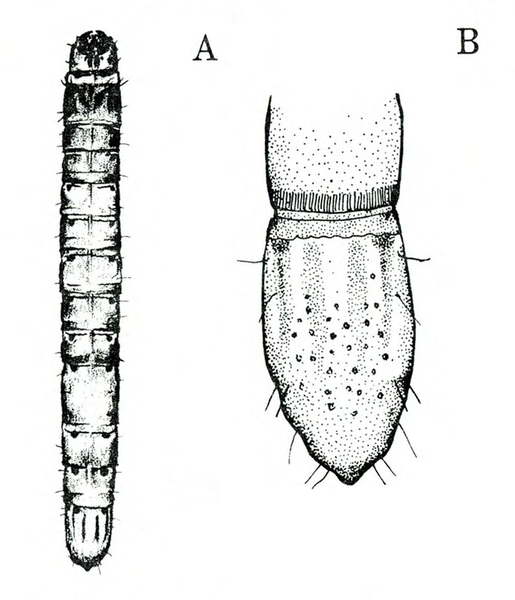

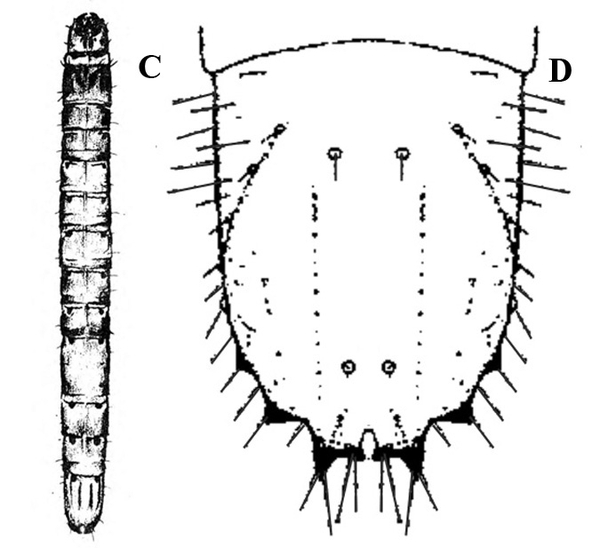

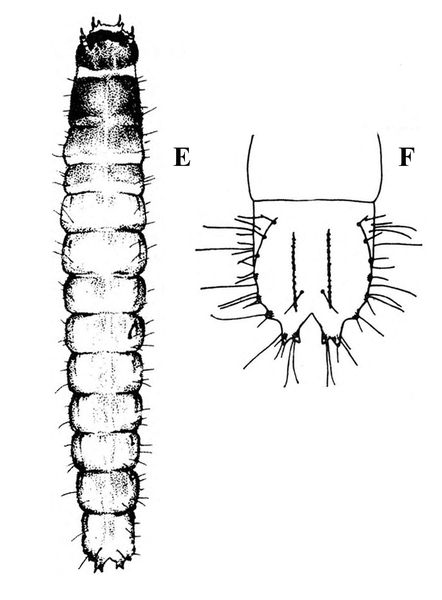

- Wireworms-–Pest wireworms have slender, wirelike larvae with three pairs of short legs near the head and a pair of prolegs near the tip of the abdomen. Evidence of injury ranges from shallow cavities to deep, ragged holes.

- Corn wireworm—This species is yellowish brown with a dark head and a body up to 1 inch long with scalloped edges on the last abdominal segment (Figure 11A–B).

- Southern potato wireworm—This species is cream colored or yellowish gray with a reddish-orange head, a body up to 11/16 inch long, and an oval notch in the last abdominal segment (Figure 11C–D).

- Tobacco wireworm—This species is white with a brown head, a body up to 3/4 inch long, and a V‑shaped notch in the last abdominal segment (Figure 11E–F).

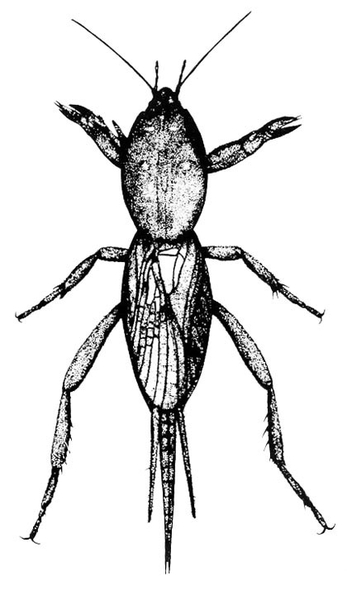

- Southern mole cricket—Adults are about 1 1/4 inches long, brown, and covered with short, fine hairs. They have short front wings; long, membranous hind wings that fold under the forewings; and short, broad, shovel-like front legs for digging (Figure 12). Seedlings may be uprooted by the tunneling activity of mole crickets. Tunneling may severely damage the roots and tubers of potato, turnip, and sweetpotato. Heavily tunneled soil dries out quickly, causing additional stress to plants.

Blister Beetles

Black blister beetle, Epicauta pensylvanica (De Geer), Meloidae, COLEOPTERA

Clematis blister beetle, Epicauta cinerea (Forster), Meloidae, COLEOPTERA

Striped blister beetle, Epicauta vittata (Fabricius), Meloidae, COLEOPTERA

Description

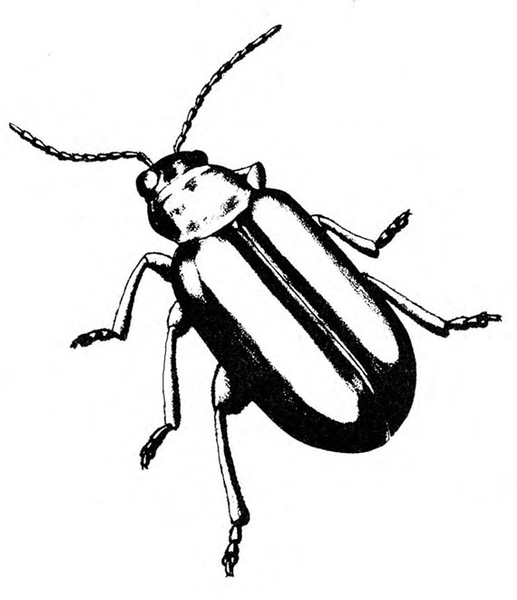

Adult—Blister beetles are slender insects 1/2 to 3/4 inch long. They have prominent heads and may be black (Figure 13A), black with yellow margins (Figure 13B), or black-and-yellow striped (Figure 13C).

Egg—The yellow, cylindrical egg is about 1/16 inch long.

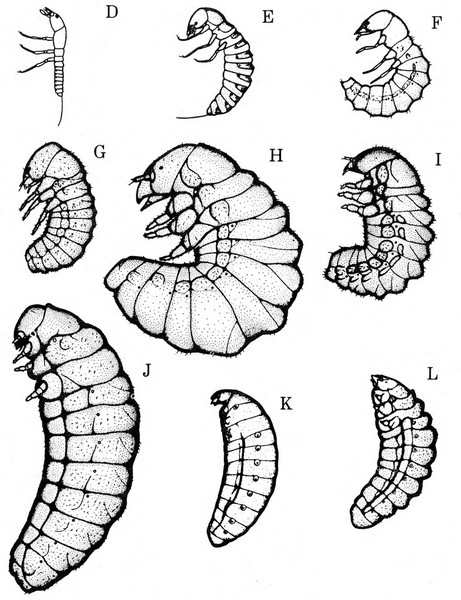

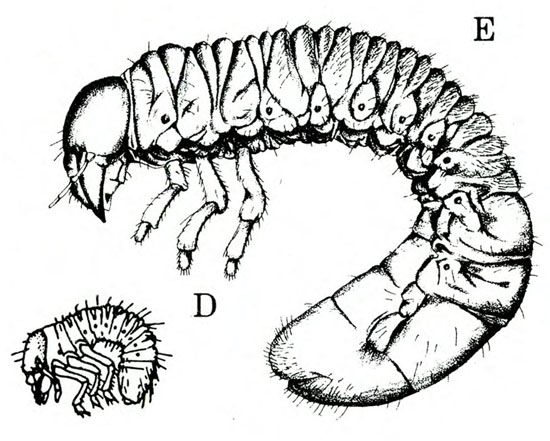

Larva—Each of the five to nine larval instars differs in size, shape, and color. Larvae can be 1/8 to 1/2 inch long, slender to plump, and white to yellow or brown. The first instar is called a triungulin, a tiny, highly active stage that seeks out grasshopper egg masses on which to feed and develop. All instars have three pairs of short ventral legs and 12 body segments, excluding the head (Figure 13D–L).

Pupa—The white, 3/8-inch-long pupa darkens gradually, beginning with the eyes (Figure 13M).

Biology

Distribution—Blister beetles are found throughout the continental United States and agricultural areas of Canada. Although fairly common in North Carolina, they are infrequently pests of importance.

Host Plants—Blister beetles have a wide host range. Besides potato, important vegetable hosts include tomato, melon, eggplant, sweetpotato, bean, pea, cowpea, pumpkin, onion, spinach, beet, carrot, pepper, radish, corn, and cabbage.

Damage—Some species of blister beetles feed on flowers, but most species are strictly foliage feeders. This latter group feeds gregariously, occasionally damaging foliage and stunting plant growth. Black, stringy excrement is often found on heavily infested plants. Blister beetles also have been known to transmit the disease organism that causes southern bacterial wilt in potatoes. Their larvae, on the other hand, are considered beneficial insects because they feed on grasshopper eggs.

Life History—Blister beetles have an unusual life cycle. They usually overwinter as sixth instar larvae 1 to 2 inches deep in the soil. In spring, resting larvae molt into active nonfeeding larvae, which soon pupate. Adult blister beetles begin to emerge in June. Adults can be found well into September but are most abundant in July. During summer months, they congregate and feed voraciously on foliage or flowers (depending upon the particular species of beetle). Two to three weeks after mating, each female deposits up to six egg masses in the soil. These masses may contain 50 to 300 eggs apiece. Active larvae, the triungulins, hatch one and a half to three weeks later and crawl about, actively searching for grasshopper egg cases to feed on. A few days after locating and feeding on these eggs, the active larvae molt and become fairly inactive. The grubs continue to feed on the eggs and molt until they are fat and almost legless. These larvae create oval hibernating chambers in the soil, molt again, and overwinter. Development usually continues the following spring, but the larvae may remain inactive for as long as two years. Some larvae molt directly into the pupal stage, bypassing the last two or more larval instar stages. In general, however, blister beetles complete one generation each year.

Control

Blister beetles often appear suddenly and may cause much damage before they are detected. Therefore, insecticides are generally applied as an emergency measure after beetles are found on a crop. Control failures usually are attributed to applying insecticides too sparingly, too late. Spot treatment is usually adequate. For recommended insecticides and rates, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Colorado Potato Beetle

Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say), Chrysomelidae, COLEOPTERA

Description

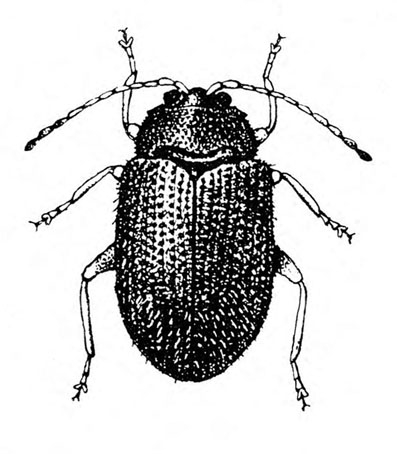

Adult—This oval, convex beetle is yellowish brown and about 3/8 to 9/16 inch long (Figure 14A and Figure 14B). It has five longitudinal black stripes on each wing cover and a variable number of black spots on the pronotum (area just behind the head).

Egg—The yellow or orange elongate eggs are deposited on end and grouped in clusters (Figure 14C). Each egg is about 1/16 inch long.

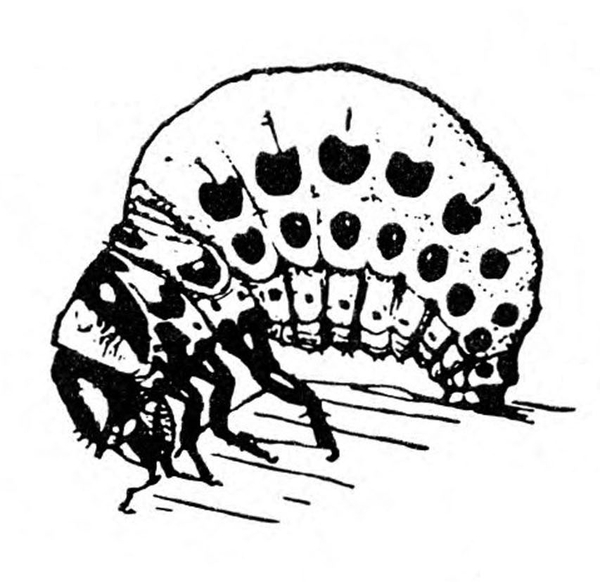

Larva—Red at first, the soft grub has a black head and black legs. As it matures, the larva turns yellowish-red or orange and develops two rows of black spots along each side of the body (Figure 14D and Figure 14E). It reaches a length of about 3/8 inch.

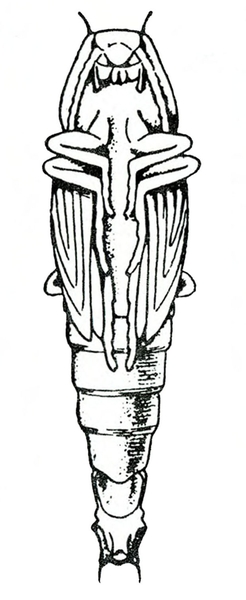

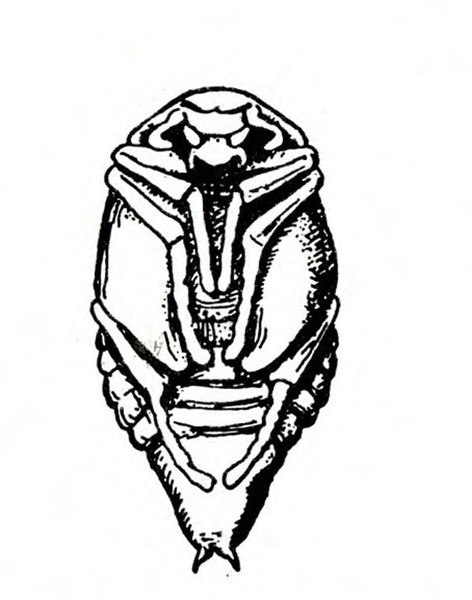

Pupa—Generally resembling the adult in shape, the pupa is about 1/2 inch long (Figure 14F).

Biology

Distribution—The Colorado potato beetle is found throughout most of North America.

Host Plants—Colorado potato beetles infest a wide variety of plants, including potato, tomato, eggplant, pepper, tobacco, ground cherry, nightshade, and other solanaceous plants.

Damage—Adult beetles and larvae feed on leaves and terminal growth of their host plants. The loss of foliage hinders development of tubers or fruit, thereby reducing yield. In cases of heavy infestation, entire plants may die. Colorado potato beetle damage often occurs in isolated spots throughout the field.

Life History—Colorado potato beetles overwinter as adults in the soil. After emerging in spring, beetles feed for a short period before mating and laying eggs. Each female deposits 300 to 500 eggs in clusters of 20 or more on the undersides of leaves. Four to nine days later, larvae emerge and feed for the next three weeks. Once mature, larvae drop to the ground and pupate in the soil. Five to ten days later, a new generation of beetles emerges. In North Carolina, at least two full generations and a partial third occur each year.

Control

Many natural enemies help keep Colorado potato beetle populations low. Birds feed on adults and larvae, while predatory bugs attack eggs and larvae (Figure 14G). Predatory bugs such as the twospotted stink bug, the brown marmorated stink bug, and the Florida predatory stink bug may be gray, brown, or brightly colored and are often shield-shaped. Two kinds of gray and black tachinid flies also parasitize larvae.

Katahdin potatoes show some resistance to Colorado potato beetles. Early treatment of commercially grown potatoes with systemic insecticides usually controls overwintering beetles and early-hatching larvae. However, some insect activity may persist around the field. The application of a foliar insecticide is not recommended until the first eggs have hatched. As soon as damage is noticed, treatment should begin. Chemical control is directed toward the first Colorado potato beetle generation because the buildup of subsequent generations may cause severe damage and defoliation. In some cases, spot treatments may be effective. For recommended insecticides and rates, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

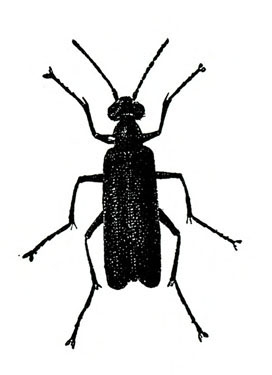

Flea Beetles

Palestriped flea beetle, Systena blanda Melsheimer, Chrysomelidae, COLEOPTERA

Potato flea beetle, Epitrix cucumeris (Harris), Chrysomelidae, COLEOPTERA

Tobacco flea beetle, Epitrix hirtipennis (Melsheimer), Chrysomelidae, COLEOPTERA

Description

Adult—The potato flea beetle is almost 1/8 inch long and brownish-black to black in color (Figure 15A). The equally small tobacco flea beetle is yellowish brown with a dark band across the wings (Figure 15B). Almost 1/8 to 3/16 inch in length, the palestriped flea beetle has a pale-yellow, brown, or black body, a reddish head, and one light-colored stripe along each wing cover (Figure 15C).

Egg—The tiny, elongate egg is white when first deposited and may darken before hatching.

Larva—The slender, cylindrical grub has a whitish body, a brown head, and three pairs of tiny legs near its head (Figure 15D). Potato and tobacco flea beetle larvae measure up to 3/16 inch long when fully grown. The mature larva of the palestriped flea beetle is slightly longer than 1/4 inch.

Pupa—The white pupa approximately resembles the adult in size and shape (Figure 15E). As it matures, it darkens gradually.

Biology

Distribution—The potato flea beetle occurs from Maine into the Carolinas and westward into Nebraska. Although the tobacco flea beetle is fairly generally distributed, it is primarily a problem in the South. The palestriped flea beetle occurs in most areas of the United States, with its northern limits in Utah, Colorado, Idaho, and New York.

Host Plants—Potato and tobacco flea beetles infest solanaceous plants such as tomato, potato, tobacco, pepper, and horsenettle. The palestriped flea beetle, however, is a more general feeder. Its hosts include potato, corn, eggplant, tomato, pea, bean, watermelon, pumpkin, sweetpotato, peanut, oats, cotton, grape, pear, and strawberry.

Damage—Flea beetles attack foliage, leaving small, round holes. Most serious injury occurs early in the growing season, and infested leaves eventually die. In addition, potato flea beetles may transmit early blight (Alternaria solani). Generally, flea beetles are much less of a problem on potato than on other solanaceous crops.

Life History—Flea beetles overwinter as adults among debris in or near fields of host plants. They resume activity in spring and feed on weedy hosts until crop hosts are available. Eggs, deposited in soil near the bases of host plants, may require a week or more to hatch. Grubs feed on or in roots, tubers, and lower stems for three to four weeks before pupating. After a pupal period of seven to ten days, a new generation of beetles emerges. The palestriped flea beetle completes only one generation each year. Potato and tobacco flea beetles produce three to four annual generations in North Carolina.

Control

Cultural methods are primary sources of defense against flea beetle infestations. It is important to keep fields free of weeds. Destruction of plant residues, especially piles of culled potatoes and trash where beetles hibernate, prevents a large buildup of populations. Late planting favors growth of the host plant over establishment of flea beetles. Covering beds of seedlings with a gauzelike material prevents beetle entry.

A number of insecticides—granular and foliar—are available to control adult flea beetles. On potatoes, an in-furrow insecticide application at planting can prevent flea beetle damage early in the season. For control throughout the season on all vegetable crops, spray plants when adults appear and repeat as needed. For recommended insecticides and rates, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

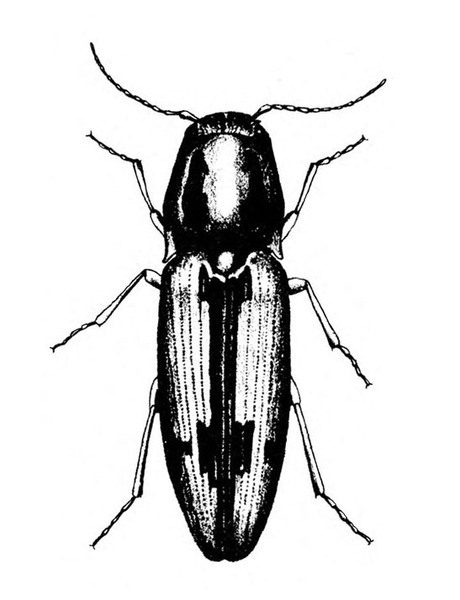

Corn Wireworm

Melanotus communis Gyllenhal, Elateridae, COLEOPTERA

Description

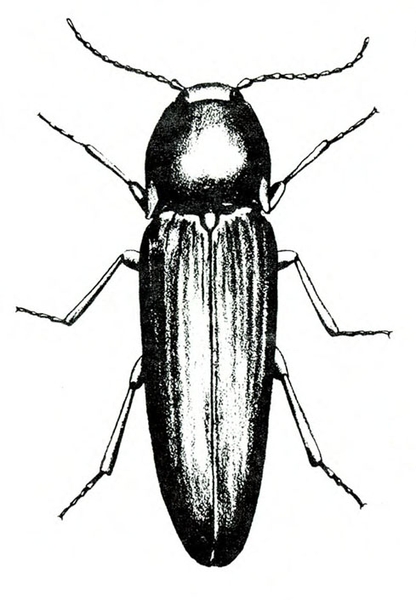

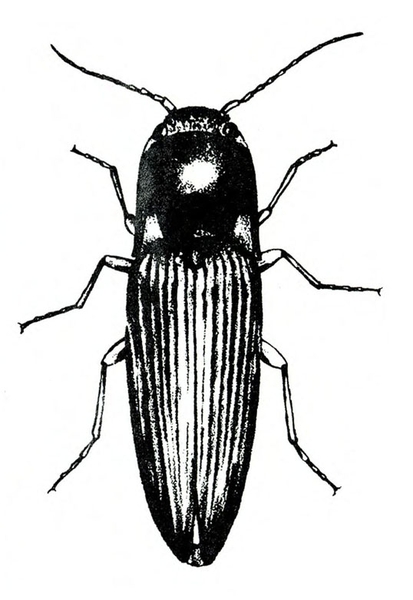

Adult—The corn wireworm adult is a hard, slick, reddish-brown to black “click beetle” about 1/2 inch long (Figure 16A).

Egg—The white, glistening egg is oval to spherical in shape and about 1/64 inch long.

Larva—A wireworm larva has three pairs of short legs near its head. The corn wireworm has a pale-yellow to reddish-brown body, a brown, flattened head, and a scalloped last abdominal segment (Figure 16B–C). When fully grown, this wireworm is 3/4 to 1 inch long.

Pupa—The white, soft-bodied pupa has no protective covering and is about the same size and shape as the adult (Figure 16D).

Biology

Distribution—The corn wireworm can be found throughout the United States, but it is particularly common in the midwestern and southeastern states. Damage tends to be prevalent in plantings that follow sod or no-till corn.

Host Plants—The corn wireworm feeds on the roots of many grasses, including corn and many small-grain crops. It may also attack the roots, seeds, and tubers of many flower and vegetable crops, especially potatoes and sweetpotatoes. This species has been known to infest tobacco.

Damage—This wireworm creates holes in potato and sweetpotato roots similar to those caused by the tobacco and southern potato wireworms. However, due to the larger size of this species’ larva, the holes are noticeably larger and deeper. Damaged roots and tubers are downgraded or discarded. The corn wireworm is the most damaging wireworm in the more northern sweetpotato-growing areas.

Life History—The corn wireworm has a six-year life cycle. In May or June of the first year, adults (beetles) deposit eggs singly among the roots of grasses. First-instar larvae emerge in July and begin feeding on roots. Larvae continue to develop throughout the summer and overwinter in the ground as second instars during the first year; most of these immatures remain in the larval stage for five years, although life cycles as short as three years have been reported. In late July or August of the sixth year, mature larvae construct oval cells 10 to 20 inches deep in the soil and pupate. Corn wireworm beetles emerge about 18 days later and feed on pollen before hibernating in protected areas. They become active and deposit eggs the following May or June.

Control

Control practices include avoiding land previously planted in sod or out of production. The use of fumigants for nematode control prior to planting will also provide some control of this soil inhabitant. Traditional applications of a granular insecticide over the row in late July are now thought to be of little value against this wireworm species. For up-to-date recommended insecticides and rates, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Potato Leafhopper

Empoasca fabae (Harris), Cicadellidae, HEMIPTERA

Description

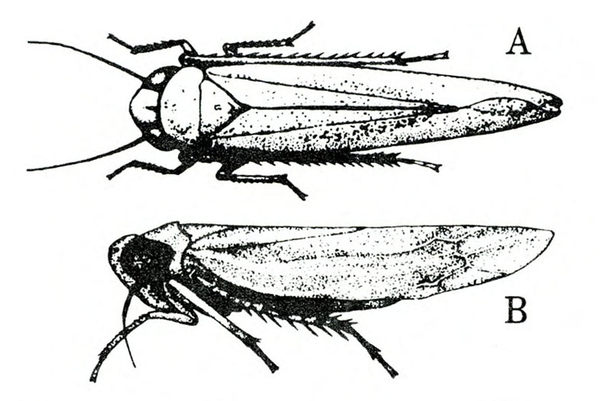

Adult—Because many species of leafhoppers look alike, entomologists studying these insects must rely heavily on examination of internal genital structures, as well as external features, to distinguish various species. About 1/8 inch long and generally spindle-shaped, the potato leafhopper has a green body with very small, yellowish, pale, or dark-green spots (Figure 17A–B). Though it can fly, the leafhopper usually jumps when disturbed.

Egg—The tiny, white egg is elongate (Figure 17C).

Nymph—Several nymphal stages exist, each of which is wingless and smaller than the adult. Though paler, the nymph is colored similarly to the adult (Figure 17D–H).

Biology

Distribution—During summer, potato leafhoppers are found from the Atlantic Coast to the Rocky Mountains. They are absent throughout most of the winter months, which they spend in the Gulf states. Leafhoppers migrate into North Carolina in mid-May and become established on a wide range of plants throughout the growing season.

Host Plants—Potato leafhoppers feed on more than 200 cultivated and wild plants. In addition to fruit trees and forage crops, they infest vegetables such as bean, potato, eggplant, and rhubarb.

Damage—Potato leafhopper nymphs and adults feed on the undersides of leaves. By extracting sap, they cause stunting of plants, curling of leaf margins, and crinkling of the upper surfaces of leaves. While feeding, leafhoppers also inject a toxic saliva into plants that, in most vegetable hosts, causes a condition known as hopperburn. This disease is characterized by a yellowing of the tissue at the tips and margins of leaves, which increases until the leaves die. Symptoms of leafhopper damage are sometimes confused with drought stress.

Life History—Potato leafhoppers winter in the Gulf states and migrate northward each year on spring winds. They arrive in North Carolina by mid-May. Three to ten days after mating, females use their sharp ovipositors to thrust eggs into the main veins or petioles of leaves. Each female leafhopper lives a month or longer and produces an average of two to three eggs daily. Eggs hatch in about ten days, and the nymphs mature in about two weeks. Nymphs usually develop on the leaves on which they hatched from eggs. They molt five times before becoming adults. Mating occurs about 48 hours after maturation, and the life cycle is repeated. Three or four generations are produced each year in North Carolina.

Control

The potato variety Delus is highly resistant to potato leafhoppers. Using systemic insecticides at planting or contact insecticides as necessary throughout the season will adequately control these pests. For up-to-date recommended insecticides and rates, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

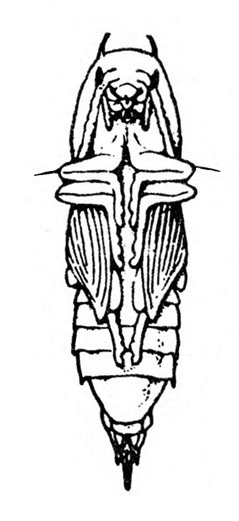

Potato Tuberworm

Phthorimaea operculella (Zeller), Gelechiidae, LEPIDOPTERA

Description

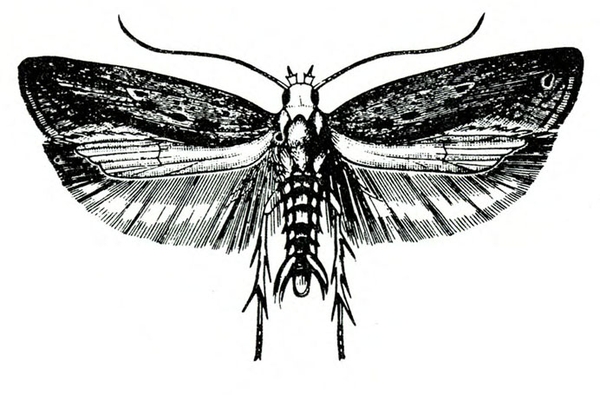

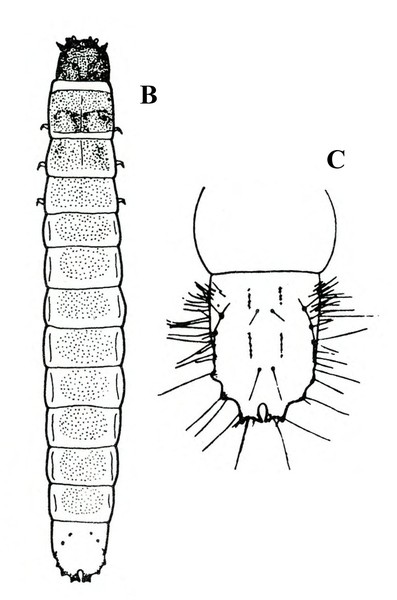

Adult—The small, slender moth has narrow gray forewings with dark-brown spots (Figure 18A). The hind wings are yellowish brown. Both sets of wings are fringed—near the base of the forewings and along the lower margin of the hind wings. The moth's body is about 5/16 inch long, and its wingspan is about 1/2 inch. The female is slightly larger than the male.

Egg—The oval egg is almost 1/32 inch long. Pearly white when first deposited, it gradually turns yellow and finally brown.

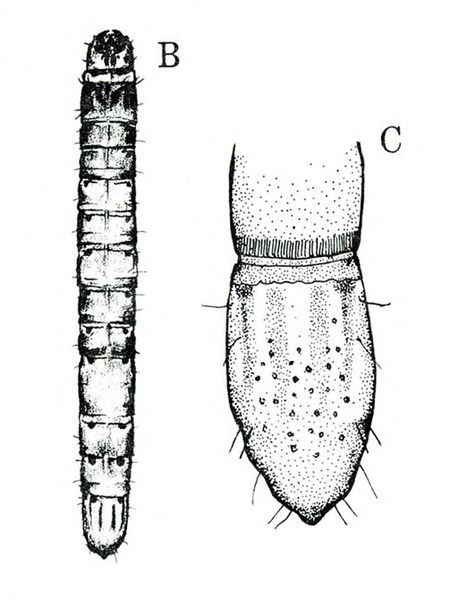

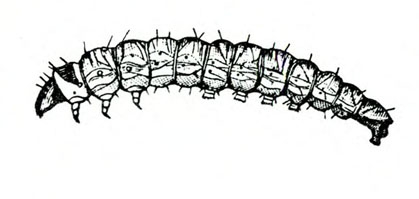

Larva—Upon hatching, the larva is creamy white with a dark-brown head and prothorax (area immediately behind the head). The larva varies from green to pink as it matures and just before pupation takes on a purplish cast. The larva is 1/2 to 3/4 inch long when fully grown (Figure 18B).

Pupa—White with green blotches at first, the spindle-shaped pupa soon turns brown (Figure 18C). It is about 5/16 inch long and enclosed in a flimsy, white, silken cocoon.

Biology

Distribution—The potato tuberworm is a cosmopolitan pest, occurring in most areas where potatoes or other solanaceous plants are grown. It occurs in at least 25 states from the Atlantic to the Pacific coasts.

Host Plants—The potato tuberworm mainly attacks potato foliage and tubers but also infests tobacco, tomato, eggplant, pepper, jimsonweed, nightshades, and horsenettle.

Damage—Potato tuberworm larvae mine leaves, petioles, and stems of host crops and bore into potato tubers and, occasionally, tomato fruits. Tuberworms feed and tunnel between upper and lower surfaces of leaves, creating grayish papery blotches that become brownish and very brittle; such injury is usually concentrated on older lower leaves (Figure 18D).

Caterpillars enter tubers near the ground by moving through cracks in the soil. Tubers covered with at least 2 inches of soil are not vulnerable to infestation. Tubers exposed during harvest often are infested soon afterward by larvae migrating from the foliage. Therefore, infestations are likely to increase in areas where culled potatoes are allowed to remain in the field following the harvesting of the spring crop.

Larvae tunnel through potatoes, filling the cavities with excrement and webbing on which disease-causing fungi grow; such potatoes are unsightly and of little food value. Larvae usually enter tubers near eyes, covering the small entrance holes with webs and excrement. Infestations are more obvious a few days later, when a pink coloration develops in the flesh around entrance holes and more excrement is visible. Larvae cut galleries 1 to 3 inches long in the tubers, either just beneath the skin or deep in the tuber.

Life History—Potato tuberworms may overwinter as larvae or pupae in the soil or in potatoes that are not exposed to freezing temperatures. Cull dumps, storage houses, and cellars are all suitable hibernation sites. The weak-flying moths emerge in spring and dart from plant to plant when disturbed. They are most active at dusk and dawn. Each female deposits, singly, 60 to 200 eggs in four days or less. Eggs are usually deposited on rough surfaces such as potato tuber eyes or the undersides of hairy leaves. Eggs hatch three to six days later, depending on temperature. Tuberworms feed and mature in seven to ten days under ideal summer conditions but mature more slowly in cooler temperatures. When fully grown, larvae leave their host and pupate in the soil near the bases of plants, in leaf litter, or in some other suitably sheltered site. A new generation of moths emerges six to nine days later. Five or six generations occur each year.

Control

Preventive measures usually are effective in controlling the potato tuberworm. Such practices include keeping potatoes hilled so there are always at least 2 inches of soil over the tubers; cultivating or irrigating to prevent deep cracks in soil; planting fall potatoes as far as possible from the location of the spring crop; destroying culled potatoes, perhaps by feeding them to livestock; eradicating volunteer plants early in spring; harvesting potatoes soon after maturity and removing them from the field immediately after digging; storing tubers, when possible, at temperatures below 50°F; screening storage areas to deter egg-laying moths; and fumigating or steam-cleaning sacks before they are reused. Avoid planting infested seed pieces; covering newly dug potatoes with vines; and leaving piles of potatoes out overnight when egg-laying moths are active.

Tuberworms are rarely a problem in fields where frequent pesticide schedules are followed. If a field becomes infested, chemical treatment should begin at once and be repeated until the pest is controlled. For up-to-date recommendations on pesticides and rates, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Southern Mole Cricket

Neocapteriscus borellii (Giglio-Tos), Gryllotalpidae, ORTHOPTERA

Description

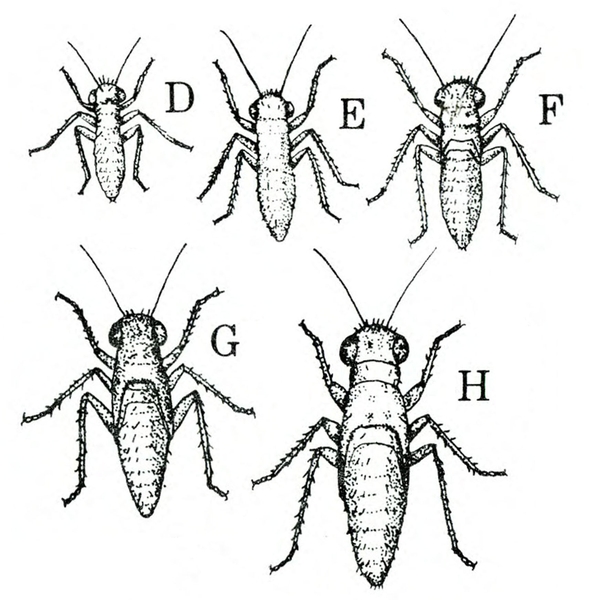

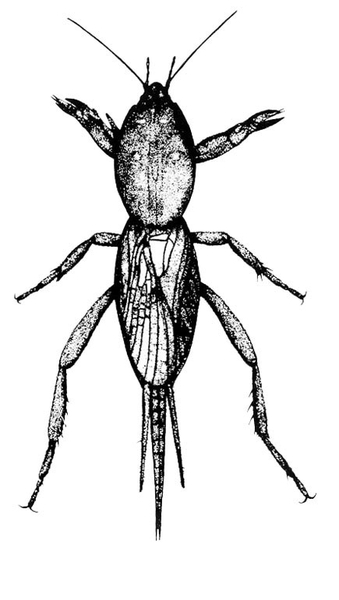

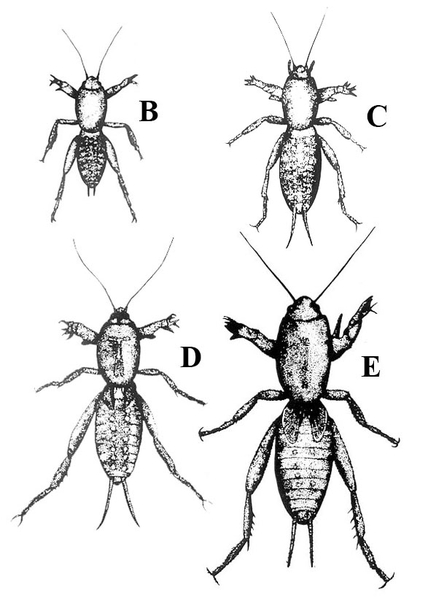

Adult—The beady-eyed adults are about 1 1/4 inches long, brown, and covered with fine, short hairs. They have short front wings; long, membranous hind wings that fold under the forewings; and short, broad, shovel-like front legs for digging (Figure 19A).

Egg—Eggs are oval and a little more than 1/8 inch long.

Nymph—Nymphs are similar in appearance to adults but are smaller and wingless (Figure 19B–E).

Biology

Distribution—The southern mole cricket occurs from North Carolina to Texas. In North Carolina, it is prevalent in the coastal plain.

Host Plants—Nymphs and adults tunnel into the soil and feed on decomposing organic matter and roots. Besides potato, targets include tobacco seedlings, turnip, sweetpotato, peanut, strawberry, and grasses.

Damage—Seedlings may be uprooted by the tunneling activity of mole crickets. Tunneling may severely damage the roots and tubers of potato, turnip, and sweetpotato. Heavily tunneled soil dries out quickly, causing additional stress to plants.

Life History—The southern mole cricket overwinters as a nymph or adult, migrating downward into the soil during cold weather. In spring, females lay eggs in cells that they construct in the soil. Each cell contains about 35 eggs. Eggs hatch in 10 to 40 days, depending on temperature. Nymphs may molt six or seven times and may become adults by winter or overwinter as nymphs. One generation occurs per year.

Control

Applying treatments before planting can control southern mole crickets. For specific chemical recommendations, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

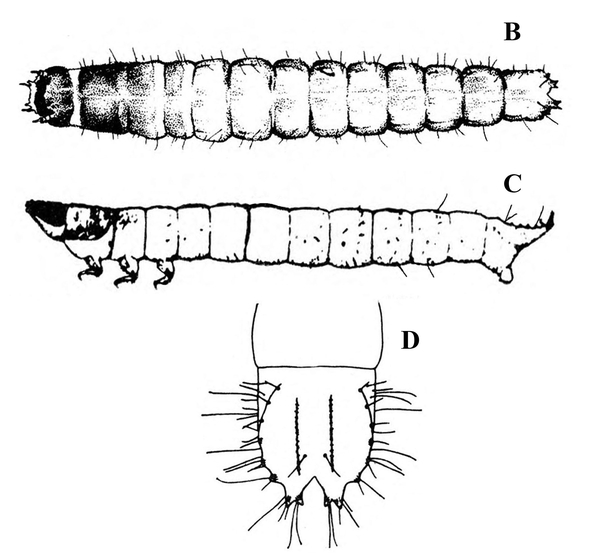

Southern Potato Wireworm

Conoderus falli (Lane), Elateridae, COLEOPTERA

Description

Adult—The adult is a brownish, oblong “click beetle” 1/4 to 5/16 inch long (Figure 20A). Its legs are light tan.

Egg—The spherical egg is smooth and translucent white with an average diameter of about 1/32 inch.

Larva—The newly hatched larva is white and later becomes cream colored or yellowish gray with a reddish-orange head. The fully grown larva is about 11/16 inch long. The last abdominal segment of this larva, unlike that of the tobacco wireworm, terminates in a closed oval notch rather than a V-shaped notch (Figure 20B–C).

Pupa—Slightly larger than the adult, the pupa is white when first formed but soon changes to a creamy yellow.

Biology

Distribution—The southern potato wireworm was apparently introduced into the United States from South America. It has been reported on coasts from North Carolina to Louisiana. Within North Carolina, it occurs mainly in the southeastern coastal plain counties.

Host Plants—The southern potato wireworm appears to prefer potato tubers. It also frequently attacks newly transplanted tobacco seedlings, sweetpotato roots, carrots, corn seedlings, and stems of tomato transplants. Less frequently damaged hosts are beet roots and the fruits of strawberry, cantaloupe, watermelon, and tomato that touch the soil surface.

Damage—Wireworms chew ragged holes in roots. A single root often has 10 or more small holes. Early feeding appears as large, shallow cavities. Later feeding creates ragged, deep holes. This wireworm usually attacks sweetpotatoes late in the season.

Life History—The biology of the southern potato wireworm has not been studied in North Carolina. In South Carolina, adults are found in fields throughout the year. Two generations occur annually. Adults from overwintering larvae begin to appear in large numbers during May, reaching peak abundance in June. Each first-generation female lays an average of 36 eggs. They hatch into the "short-cycle" brood, which matures in 42 to 109 days. Adults of the short-cycle brood are abundant in late August and September. They mate and lay eggs of the "long-cycle" brood, or the overwintering generation, which matures in 239 to 318 days.

Control

No insect parasites or predators of this wireworm have been discovered. Three disease-causing agents—a fungus, a protozoan, and a parasitic nematode—have been identified from wireworms, but their usefulness in the control of this wireworm has not been determined.

Do not plant susceptible crops in fields that were planted with a winter crop, not plowed during the fall and winter, or recently planted in row crops. No resistance to this pest has been found in Irish potatoes. The sweetpotato varieties Nugget and All Gold, however, do possess some resistance.

Insecticides for the control of wireworms can be applied in-furrow at planting, broadcast and incorporated into the soil, or broadcast later over the top of sweetpotato foliage. This wireworm has developed resistance to chlorinated hydrocarbons and organophosphate insecticides. For specific information about insecticides and rates, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Tobacco Wireworm

Conoderus vespertinus (Fabricius), Elateridae, COLEOPTERA

Description

Adult—The adult, called a “click beetle,” is reddish brown with yellow markings, oblong, and about 5/16 inch in length (Figure 21A).

Egg—The newly laid egg is spherical, white, and almost 1/32 inch in diameter.

Larva—The newly hatched larva is about 1/16 inch long and grows to a length of 9/16 to 3/4 inch. Except for the head, which is tinged iron-brown, the larva is white. Its last abdominal segment terminates in a V-shaped notch (Figure 21B–D).

Pupa—The brown pupa (Figure 21E) is slightly larger than the adult; it occurs in the soil near the food source.

Biology

Distribution—The tobacco wireworm is common in the southeastern states. In North Carolina, it occurs throughout most of the coastal plain. It is more prevalent in areas where tobacco, cotton, or corn are the main crops than in areas planted chiefly with truck crops.

Host Plants—The tobacco wireworm apparently prefers tobacco, but it feeds on a variety of other plants, including cotton, corn, potato, sweetpotato, and various truck crops.

Damage—Damage appears as ragged holes in the roots. Often, a single root may have 10 or more small holes. Early feeding appears as shallow but wide cavities. Later feeding appears as ragged, deep holes. Damaged tubers are downgraded or discarded.

Life History—In summer, each female lays about 240 eggs singly on or slightly beneath the soil surface. Larvae hatch and feed on roots of corn, tobacco, potato, and other host plants. Winter is passed in the larval stage. Pupation occurs in the soil in June. Adults emerge during early summer and are most active from late June through July. There is only one generation per year. The typical life cycle requires about 348 days in North Carolina: egg stage (10 days), larval stage (315 days), pupal stage (10 days), and pre-oviposition period (13 days).

Control

Crop rotation is an effective management tool for control and should be practiced where possible. Do not plant wireworm-susceptible crops in fields planted in a winter cover crop, those not plowed during fall and winter, and those not recently planted in row crops. Low soil moisture, high summer temperatures, diseases, predation, and cannibalism all seem to reduce wireworm populations.

Insecticides to control wireworms can be applied in-furrow at planting, broadcast, and incorporated into the soil or broadcast later over the top of sweetpotato foliage. For specific information on insecticides and rates, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

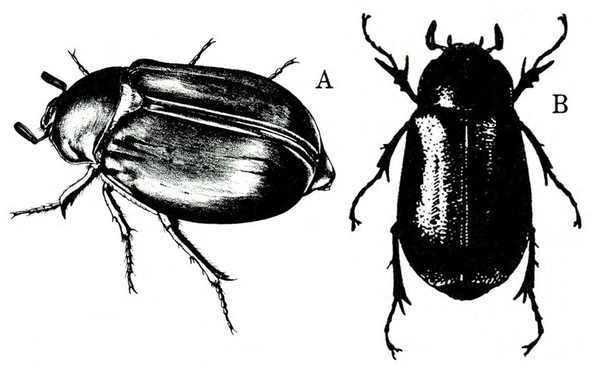

White Grubs

Phyllophaga spp., Scarabaeidae, COLEOPTERA

Description

Adult—Known as May beetles, the shiny, reddish-brown to black adults are 3/4 to 1 inch long (Figure 22A–B).

Egg—A dull, pearly white when first deposited, the oval to spherical egg (Figure 22C) turns dark just before hatching. It may be 1/16 to 1/8 inch in diameter. Small masses of 15 to 20 eggs are laid in cells in the soil.

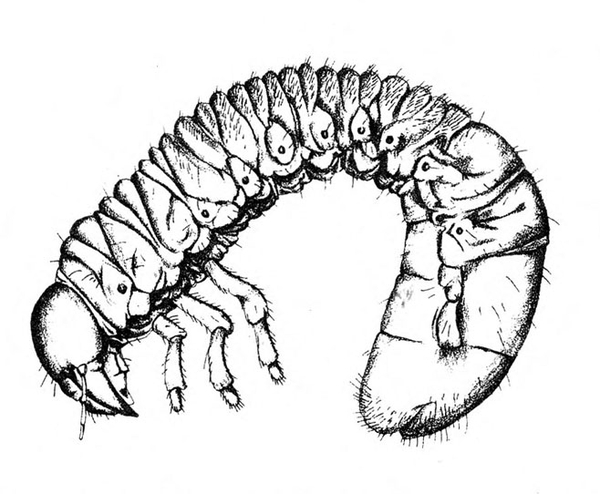

Larva—The young grub is creamy white and about 3/16 inch long. Mature grubs are about 13/16 inches long (Figure 22D–E). The C-shaped grub has a distinct brown head; a shiny, smooth body; and three pairs of legs just behind the head. Two rows of hairs on the underside of the last segment distinguish May beetle grubs from similar grubs.

Pupa—About the same size as the adult, the pupa may be creamy white, pale yellow, or dark brown (Figure 22F).

Biology

Distribution—More than 200 species of white grubs are found throughout North America. During summer, these beetles are often seen flying around lights at night. Populations of grubs tend to be highest in older plantings of sod or soils high in decomposing organic matter. In North Carolina, they occur in all counties but are most numerous from the piedmont to the coast.

Host Plants—White grubs attack the roots of many cultivated crops in addition to pasture, field grasses, and nursery plants. Besides potato, some common hosts are corn, sorghum, soybean, strawberry, barley, oats, wheat, rye, bean, turnip, and tobacco. Adult beetles are strongly attracted to fragrant flowers and ripe fruits.

Damage—White grubs are among the most destructive soil pests in North America. In addition to severing roots and stems of potatoes, white grubs feed on tubers, leaving large, shallow, circular holes. The infested plants often do not show symptoms on aboveground parts. As a result, considerable damage may be done before the grub problem is discovered. Where infestations are heavy, the soil may become soft and fluffy due to grub movement.

Life History—In spring, overwintering adults emerge from the soil at dusk, feed on the leaves of trees, and mate during the night. At dawn, they return to the ground, where females lay 15 to 20 pearly white eggs in cells a few inches below the surface. Eggs hatch in three to four weeks. Newly hatched grubs feed on plant roots throughout the summer and complete one-third of their development before fall. These grubs burrow below the frost line to a depth of 4 feet and hibernate.

The following spring, May beetle grubs return close to the soil surface and resume feeding. They continue to feed and develop throughout the growing season and overwinter again the second year. The grubs become fully grown by late spring of the third year. At this time, they dig cells in the soil and pupate. Pupae become adults by late summer, but the beetles do not leave the ground. New May beetles overwinter in their earthen cells and emerge the following spring to feed and mate. White grubs complete one generation every three years.

Control

Several cultural practices help reduce white grub populations. Late summer or early fall plowing may expose larvae, pupae, or adults to predaceous birds. Crop rotation, however, is the most effective control method. Corn and potatoes should be rotated with resistant or less susceptible crops like clovers or other legumes. Potatoes should never follow grasses in a rotation, especially in years following a heavy beetle flight.

Other Resources

General

Gould, G. E. Insect Pests of Muck Crops. Circular 338. Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Agricultural Experiment Station, 1948.

Shands, W. A., and B. L. Landis. Potato Insects: Their Biology and Biological and Cultural Control. Agriculture Handbook 264. USDA,1964.

Shands, W. A., and B. L. Landis. Controlling Potato Insects. Farmers' Bulletin 2168. USDA, 1970.

Simpson, G. W., and W. A. Shands. Progress on Some Important Insect and Disease Problems of Irish Potato Production in Maine. Bulletin 470. Maine Agricultural Experiment Station, 1949.

Blister Beetles

Capinera, J. L. Common Name: Striped Blister Beetle, Scientific Name: Epicauta vittata (Fabricius) (Coleoptera: Meloidae). Featured Creatures. Publication Number: EENY–280. Entomology and Nematology, FDACS/DPI, EDIS, University of Florida, 2021.

Gilbertson, G. I., and W. R. Horsfall. Blister Beetles and Their Control. Bulletin 340. South Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station, 1940.

Horsfall, W. R. Biology and Control of Some Common Blister Beetles in Arkansas. Bulletin 436. Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station, 1943.

Colorado Potato Beetle

Hazzard, R. “Colorado Potato Beetle, Management.” UMass Extension Vegetable Program, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2022.

Jacques, R. L., Jr., and T. R. Fasulo. Common Name: Colorado Potato Beetle, Scientific Name: Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say) (Insecta: Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Featured Creatures. Publication Number: EENY–146. Entomology and Nematology, FDACS/DPI, EDIS, University of Florida, 2015.

Corn Wireworm

Fenton, E. A. “Observations of the Biology of Melanotus communis and Melanotus pilosus.” Journal of Economic Entomology 19 (1926): 502–4.

Harsimran K., et al. Common Name: Corn Wireworm, Scientific Name: Melanotus communis Gyllenhal (Insecta: Coleoptera: Elateridae). Featured Creatures. Publication Number: EENY–584. Entomology and Nematology, FDACS/DPI, EDIS, 2020.

Quate, L. W., and S. E. Thompson. “Revision of Click Beetles of the Genus Melanotus in America, North of Mexico (Coleoptera: Elateridae).” In Proceedings of the United States National Museum 121, no. 3568 (1967): 1–85.

Riley, T. J., A. J. Keaster, and W.R. Enns. “Four Species of Wireworms of the Genus Melanotus Associated with Corn in Missouri.” Journal of Economic Entomology 67 (1974): 793.

Riley, T. J., and A. J. Keaster. “Wireworms Associated with Corn: Identification of Larvae of Nine Species of Melanotus from the North Central States.” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 72 (1979): 408–14.

Flea Beetles

Capinera, J. L. “Parasitism of the Palestriped Flea Beetle (Chrysomelidae) by an Allantonematid Nematode Howardula sp.: Effect of Parasitism on Adult Longevity and Sugarbeet Foliage Consumption.” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 72, no. 3 (1979): 348–49.

Chittenden, F. H. “Biologic and Other Notes on the Flea-Beetles Which Attack Solanaceous Plants.” In Some Insects Injurious to Garden and Orchard Crops (Bulletin No. 19), 85–90. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Division of Entomology, 1899.

Chittenden, F. H. “Notes on Flea-Beetles.” In Some Insects Injurious to Vegetable Crops (Bulletin No. 33), 110–117. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Division of Entomology, 1902.

Dominick, C. B. Life History of the Tobacco Flea Beetle. Bulletin 355. Virginia Agricultural Experiment Station, 1943.

Dominick, C. B. “Late Season Feeding and Emergence of the Tobacco Flea Beetle.” Journal of Economic Entomology 61 (1968): 1743–44.

Dominick, C. B. “Overwintering and Spring Emergence of the Tobacco Flea Beetle.” Journal of Economic Entomology 64 (1971): 88–89.

Drake, C. J., and H. M. Harris. “The Pale-Striped Flea Beetle, A Pest of Young Seedling Onions.” Journal of Economic Entomology 24, no. 6 (1931): 1132–37.

Potato Leafhopper

Delong, D. M. Biological Studies on the Leafhopper Empoasca fabae as a Bean Pest. Technical Bulletin No. 618. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1938.

Fenton, E. A., and A. Hartzell. “Bionomics and Control of the Potato Leafhopper.” Iowa Agricultural Experiment Station Research Bulletin 78 (1923): 377–440.

Gyrisco, G. G., et. al. The Literature of Arthropods Associated with Alfalfa: IV. A Bibliography of the Potato Leafhopper, Empoasca fabae (Harris) (Homoptera: Cicadellidae). Special Publication 51. Illinois Agricultural Experiment Station, 1978.

Medler, J. T. “Migration of the Potato Leafhopper—A Report on a Cooperative Study.” Journal of Economic Entomology 50 (1957): 493–97.

Poos, F. W. “Biology of the Potato Leafhopper, Empoasca fabae (Harris), and Some Closely Related Species of Empoasca.” Journal of Economic Entomology 25 (1932): 639–46.

Poos, F. W., and N. H. Wheeler. Studies on Host Plants of the Leafhoppers of the Genus Empoasca. Technical Bulletin 850. USDA, 1943.

Potato Tuberworm

Graf, J. E. The Potato Tuber Moth. Bulletin 427. USDA, 1917.

Morgan, A. C., and S. E. Crumb. The Tobacco Splitworm. Bulletin No. 59. USDA, 1914.

Whelton, A. M., and J. A. Wyman. “Potato Tuberworm Damage to Potatoes Under Different Irrigation and Cultural Practices.” Journal of Economic Entomology 72 (1979): 261.

Southern Mole Cricket

Capinera J. L., and N. C. Leppla. Common Name: Southern Mole Cricket, Scientific Name: Neoscapteriscus borellii (Giglio-Tos) (Insecta: Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae). Featured Creatures. Publication Number: EENY–235. Entomology and Nematology, FDACS/DPI, EDIS, University of Florida, 2018.

Held, D., and P. Cobb. Biology and Control of Mole Crickets. Alabama A&M & Auburn Universities Extension, 2019.

Southern Potato Wireworm

Day, A., et al. The Southern Potato Wireworm: Its Biology and Economic Importance in Coastal South Carolina. Technical Bulletin No. 1443. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service and South Carolina Agricultural Research Station, 1971.

Vernon, B., and W. van Herk. “Chapter 7—Wireworms as Pests of Potato.” In Insect Pests of Potato (2nd edition): Global Perspectives on Biology and Management, edited by Andrei Alyokhin, et al., 103–148. Elsevier, 2022.

Tobacco Wireworm

Rabb, R. L. “Biology of Conoderus vespertinus in the Piedmont Section of North Carolina (Coleoptera: Elateridae).” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 56 (1963): 669–76.

White Grubs

Luginbill, P., and T. R. Chamberlin. Control of Common White Grubs in Cereal and Forage Crops. Farmers' Bulletin 1798. USDA, 1953.

Ritcher, P. O. Kentucky White Grubs. Bulletin 401. Kentucky Agricultural Experiment Station, 1940.

Publication date: June 13, 2024

AG-295

Other Publications in Insect and Related Pests of Vegetables

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.