Many pests of sweet corn go unnoticed because they are hidden within the soil, stalk, ear, or whorl. Few insects feed on exposed sites, where they could be easily detected and controlled before damage occurs. As a result, growers need to be able to recognize early signs of both pests and their injury.

A. Caterpillars that feed on exposed leaves or bore into the whorl, stalk, or ear

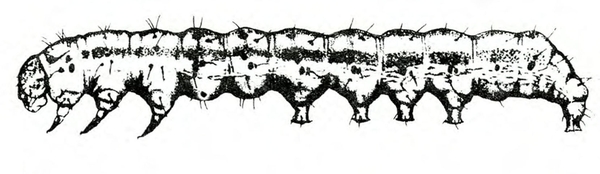

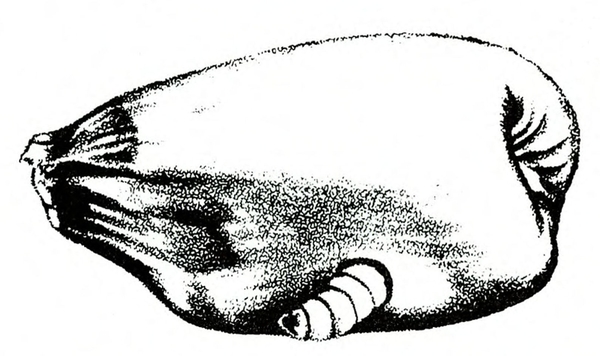

- Corn earworm (also known as tomato fruitworm)—Early instars are cream colored or yellowish green with few markings. Later instars are green, reddish, or brown with pale, longitudinal stripes and scattered black spots, moderately hairy, and up to 1 3/4 inches long with three pairs of legs and five pairs of prolegs (Figure 1). As leaves unfurl, ragged holes and soggy, brown frass (droppings) are apparent. Corn earworms feed on the tip kernels of the ear. Round emergence holes appear in the shuck.

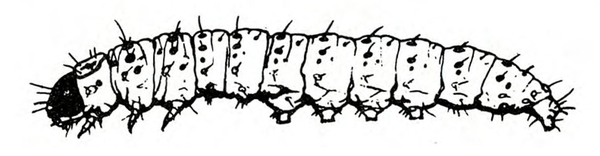

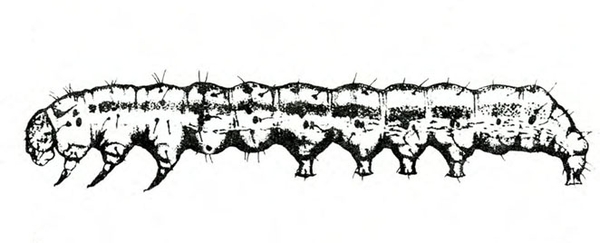

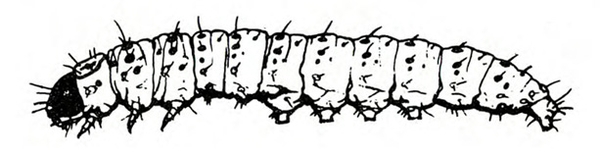

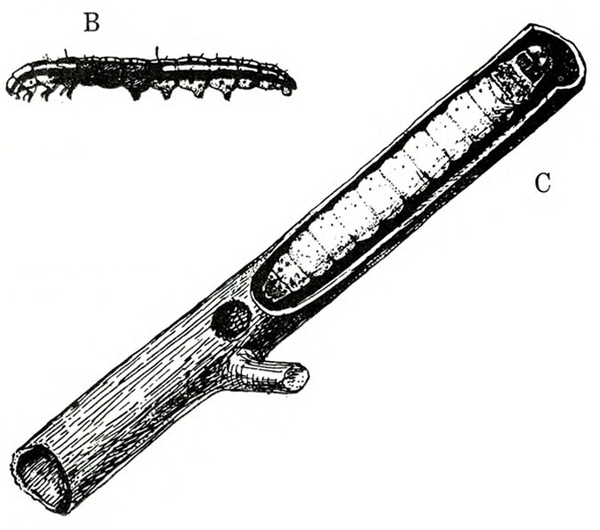

- European corn borer—The cream-colored to light-pink caterpillar has a reddish-brown to black head. Its body is up to 1 inch long with several rows of dark spots, three pairs of legs near the head, and five pairs of prolegs (Figure 2). The caterpillar bores into the stalk. Tangled frass and silk are visible near the entrance hole. They cause tassels and stalks to break, ears to drop, and ears to remain small. Pinholes are sometimes present in leaves.

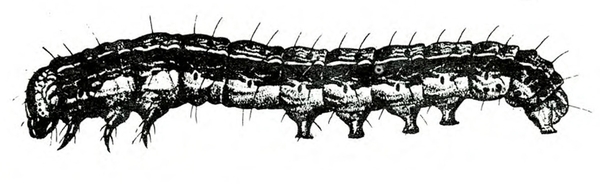

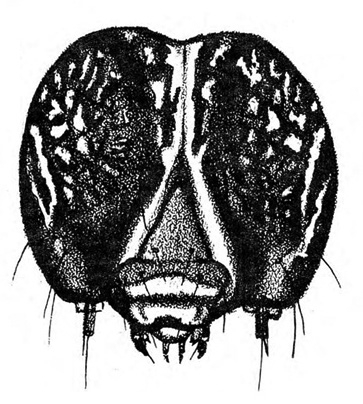

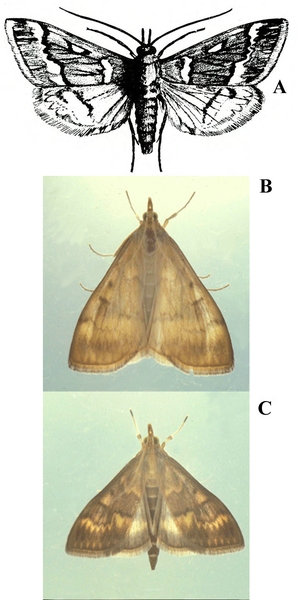

- Fall armyworm—This green, brown, or black caterpillar has a black stripe down each side and a yellowish-gray stripe down the back. The body is up to 1 5/8 inches long (Figure 3A). Its head capsule has a pale, but distinct, inverted Y (Figure 3B). Fall armyworms are rarely found in North Carolina before July but may be common later. They feed on leaves and may attack ears near the shuck. Mature larvae may bore into the stalk.

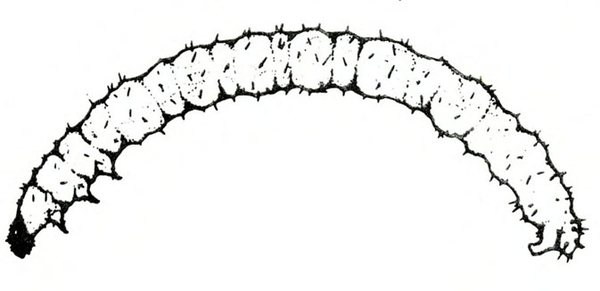

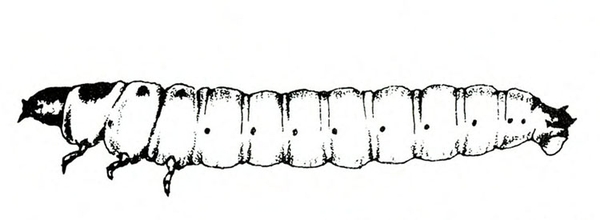

- Stalk borer—This brown worm has a dark-brown band with some paler stripes. Older worms are whitish or light purple (Figure 4). Infested plants sucker excessively and do not tassel properly, and stems sometimes lodge (bend and break). Plants that are past the whorl stage are resistant to stalk borer infestation.

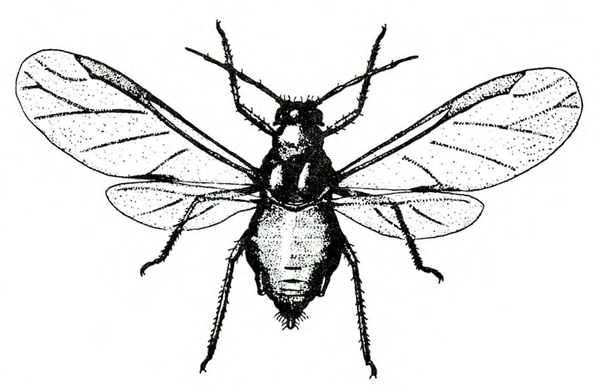

B. Pests that feed on foliage or silks

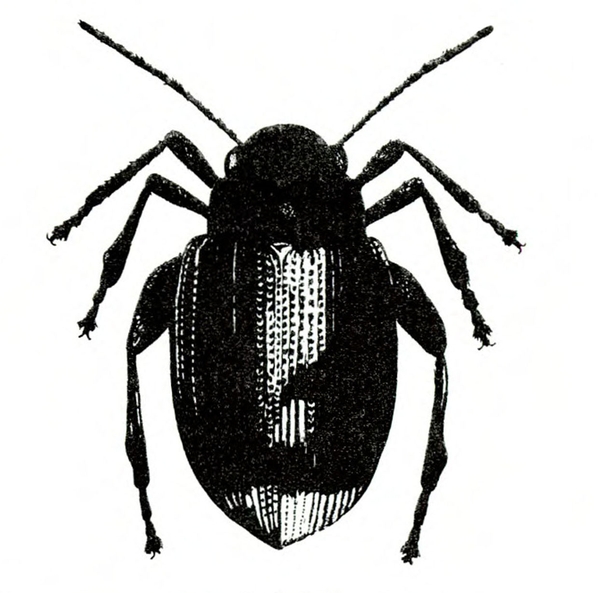

- Corn flea beetle—This black, oval insect (Figure 5) is about 1/16 to 1/8 inch long, tinged bronze or bluish-green with yellow markings on the legs. The basal antennal segment is orange. Infested foliage has tiny, round holes and bleached-out spots or stripes.

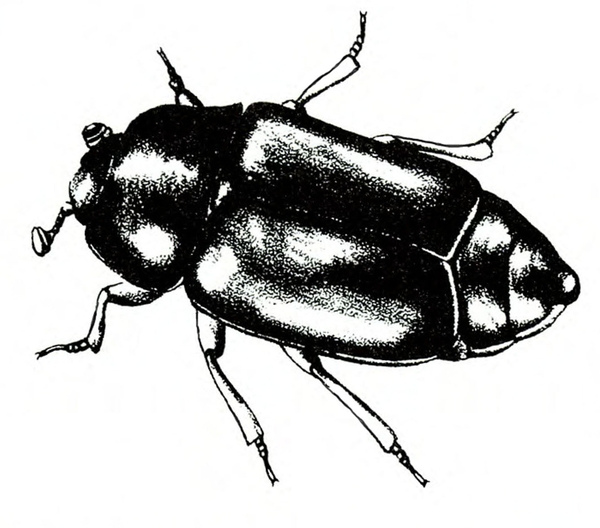

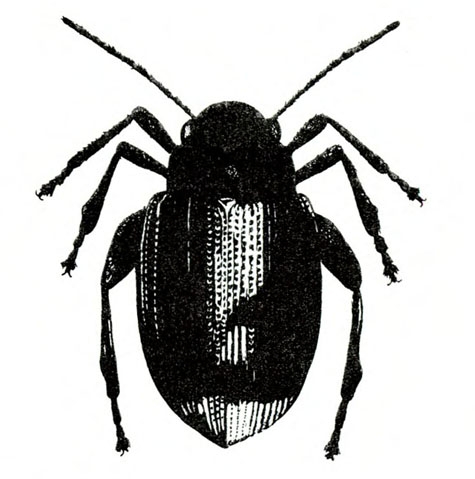

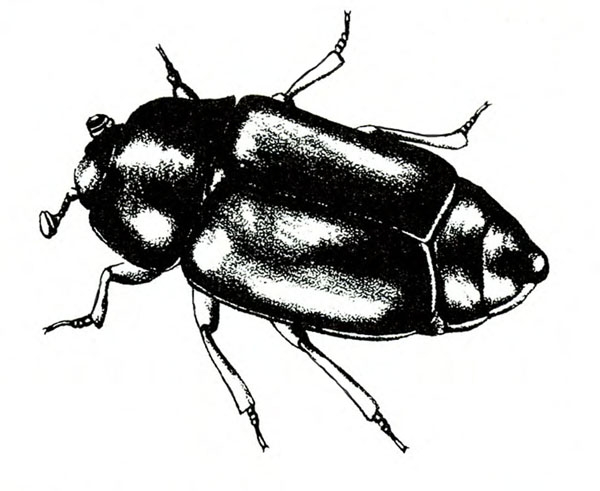

- Dusky sap beetle—This dark-gray or brown, oval-to-oblong beetle is 1/8 to 3/16 inch long, with club-like antennae (Figure 6). It feeds on ripening pollen and is found on tassels or in leaf axils where pollen has collected.

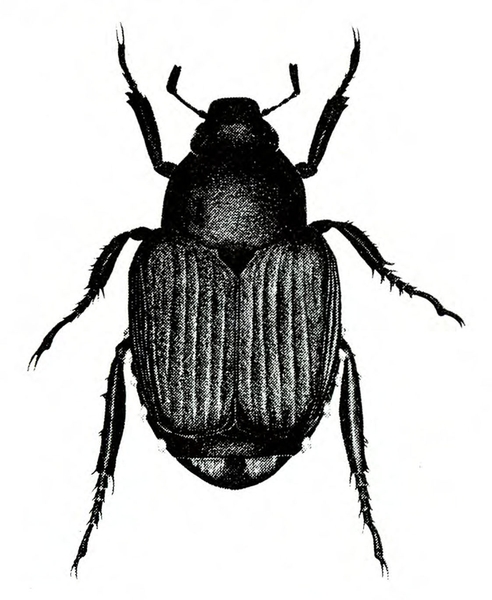

- Japanese beetle—This half-inch-long beetle is shiny metallic green with coppery brown wing covers (Figure 7). It feeds on silks and, in severe infestations, it reduces pollination and kernel formation. (For more information about Japanese beetles, see “Pests of Okra.”)

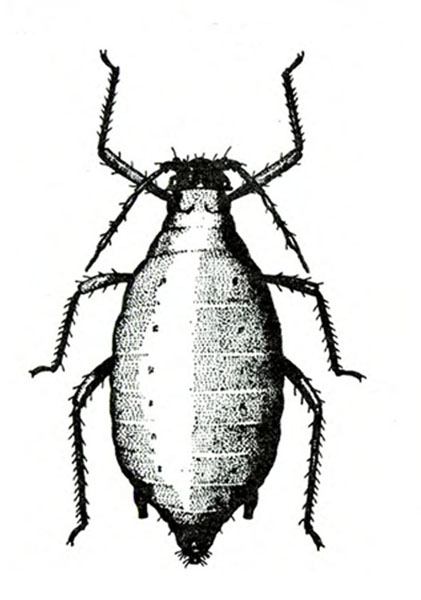

- Corn leaf aphid—This soft-bodied, pear-shaped, winged or wingless insect may be a little more than 1/16 inch long. Its body is pale bluish-green with a powdery coating and a dark area around the base or cornicles (tubes) (Figure 8). It feeds in colonies and causes leaf yellowing and deformation. Cast aphid skins and black moldy tassels, leaves, and silks indicate high aphid population.

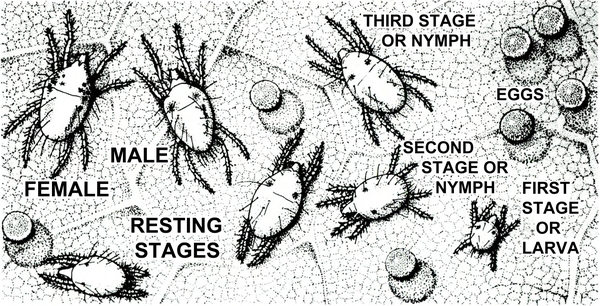

- Twospotted spider mite—Tiny (almost microscopic) and pale to dark green, these mites have two or four dark spots (Figure 9). Adults have eight legs. They feed on leaves, shucks, and silks (Figure 10). Heavily infested plants turn yellow or appear burned. Sometimes silks are completely obscured by webs and mites. (For more information about twospotted spider mites, see “Pests of Beans and Peas.”)

C. Insects that feed on and bore into roots

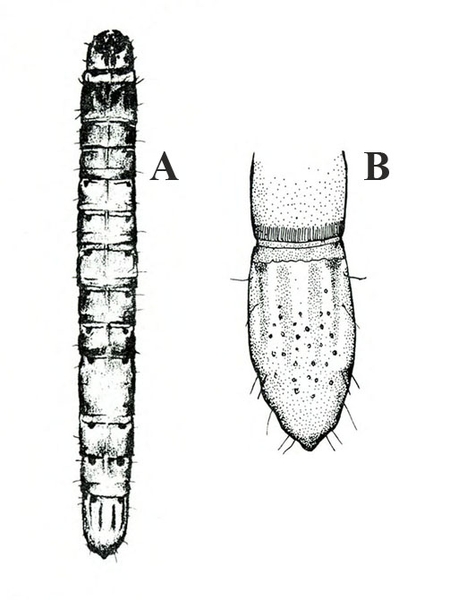

1. Corn wireworm—This wireworm is yellowish brown with a dark head. Its body is up to 1 inch long with scalloped edges on the last abdominal segment (Figure 11A–B). (For more information about corn wireworms, see “Pests of Potato.”)

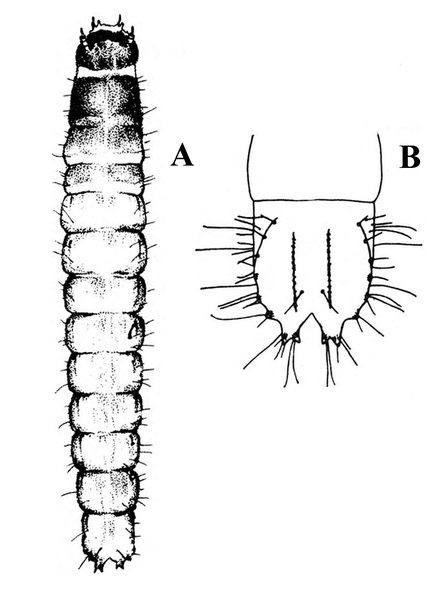

- Tobacco wireworm—This wireworm is white with a brown head. Its body is up to 3/4 inch long, and it has a V-shaped notch in the last abdominal segment (Figure 12A–B). (For more information about tobacco wireworms, see “Pests of Potato.”)

Corn Earworm (Tomato Fruitworm)

Helicoverpa zea (Boddie), Noctuidae, LEPIDOPTERA

Description

Adult—The corn earworm moth has a wingspan of 1 to 1 1/2 inches and is usually light yellowish-olive in color (Figure 13A–B). Each forewing has a dark spot near the center. The eyes are usually light green.

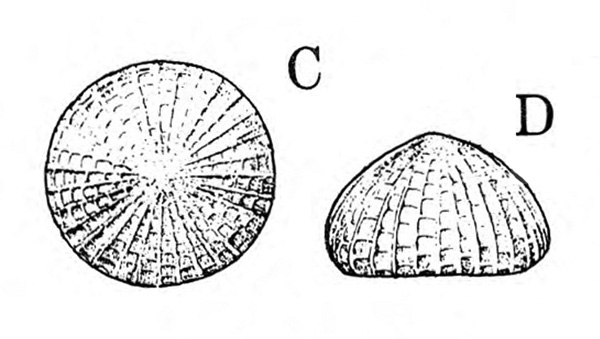

Egg—The dome-shaped egg, about 1/64 inch in diameter, is pale white when first laid and develops a reddish-brown band before hatching (Figure 13C).

Larva—The five to six larval instars vary considerably in color. Newly hatched larvae are about 1/16 inch long and yellowish white with dark head capsules. Second instars are yellowish green and frequently have orange and brown longitudinal stripes; their head capsules are reddish-brown to brown. Up to 1 3/4 inches long, later instars are greenish yellow, reddish, or brown, with pale, longitudinal stripes, raised black spots (chalazae), and brown to orange heads. All instars have five pairs of fleshy prolegs (Figure 13D).

Pupa—About 13/16 inches long and 1/4 inch wide, the pupa is reddish brown to dark brown (Figure 13F).

Biology

Distribution—This insect is found throughout most of the Western Hemisphere.

Host Plants—The corn earworm infests more than 100 plants, but corn is the preferred host. The earworm is also found occasionally on wild hosts like toadflax and vetch.

Damage—Though foliage is attacked early in the growing season, corn earworms prefer fruiting stages of their host plants. On seedlings, corn earworms devour leaves, buds, and tender new growth. On corn, first-generation larvae feed in the tightly coiled blades. As a result, numerous ragged holes appear when the blades unfurl. Wet, tan-to-brown excrement lodges in the whorl and blade axils. This condition often is referred to as "shatterworm" injury.

As vegetable crops flower and produce fruit, larvae move to these plant parts. Entrance holes of small larvae may be completely undetectable in sweet corn ears. In the corn ear, larval damage is usually confined to developing kernels in the ear tip area (Figure 13E). Round holes about 3/16 inch in diameter through the shuck are usually emergence holes rather than entrance holes.

Life History—In North Carolina, corn earworms overwinter as "resting" (diapausing) pupae more than 2 inches deep in the soil. Adults emerge in early May, mate, and seek suitable oviposition (egg-laying) sites. A high percentage of first-generation eggs are laid on the leaves of seedling corn when it is available. Once corn begins silking, however, most eggs are deposited on silks. Later in the season, as corn silks dry up, oviposition again occurs on the leaves of other hosts, including many vegetable crops. Females deposit eggs singly, each laying between 450 and 3,000 eggs. Within two to five days, the larvae emerge and begin feeding. Because this insect is cannibalistic, rarely does more than one larva develop from an ear or whorl. Larvae feed for two to four weeks, developing through five or six instars. They then burrow in the soil to pupate. Two to four weeks later, a new generation of moths emerges. At least three generations occur each year in North Carolina.

Control

Cultivating fields after harvest kills numerous pupae in the soil and exposes many to birds and other predators. Resistant sweet corn varieties are available, though they are not immune to attack. Although corn earworms may severely damage young corn, insecticides to protect ears are generally used only from silking until harvest. When corn is harvested in the coastal plain from July 10 to July 20, the infestation in ears is relatively low, even if chemical control was only fairly effective. For recommended insecticides and rates, consult the current North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Corn Flea Beetle

Chaetocnema pulicaria Melsheimer, Chrysomelidae, COLEOPTERA

Description

Adult—This oval, black beetle is tinged bronze or bluish green, has yellow markings on its legs, and is almost 1/8 inch long (Figure 14A). The basal segment of each antenna is orange.

Egg—Each white egg is almost 1/64 inch long and pointed at one end. It gradually darkens before hatching.

Larva—The slender, white, cylindrical grub has a brown head and tiny legs. It may be 1/8 to 5/16 inch long when fully grown (Figure 14B).

Pupa—The white, soft-bodied pupa resembles the adult in size and shape and gradually darkens as it matures (Figure 14C).

Biology

Distribution—The corn flea beetle occurs in most areas east of the Rocky Mountains. It infests corn all across North Carolina but appears to be more abundant in the piedmont counties.

Host Plants—Although the corn flea beetle is a general feeder, its preferred hosts are grasses. However, it periodically infests sugar beets in other states.

Damage—Corn flea beetles attack foliage, leaving small, round holes and bleached-out spots or stripes (Figure 14D). Larvae feed on roots of grasses. Direct loss caused by corn flea beetle feeding, however, is relatively insignificant. Overwintering beetles are responsible for the most economic damage because they spread Stewart’s disease, a bacterial wilt of corn. These beetles are usually most troublesome when a cold spring follows a mild winter. Under such conditions, large numbers of beetles survive the winter and attack slowly growing corn over a prolonged period. Growth is retarded, and leaves may wilt. Early maturing varieties in the mid-Atlantic and southern states are most seriously affected.

Life History—Adults generally overwinter in litter and trash around fields. Mortality tends to be high during harsh winters. In early spring, beetles move to weeds and then to corn seedlings. Eggs are scattered on soil beneath host plants. In about 10 days, larvae emerge and begin feeding on and tunneling in underground stems, roots, or tubers. They feed for three to four weeks and develop through three instars before pupating in the soil. Seven to ten days later, a new generation emerges. Three or more generations are completed each year.

Control

To prevent damage from corn flea beetle infestations, plow crop residue under and maintain good weed control to eliminate overwintering sites. Planting wilt-resistant hybrids also lessens the chances of excessive loss due to bacterial wilt. For recommended insecticides and rates, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

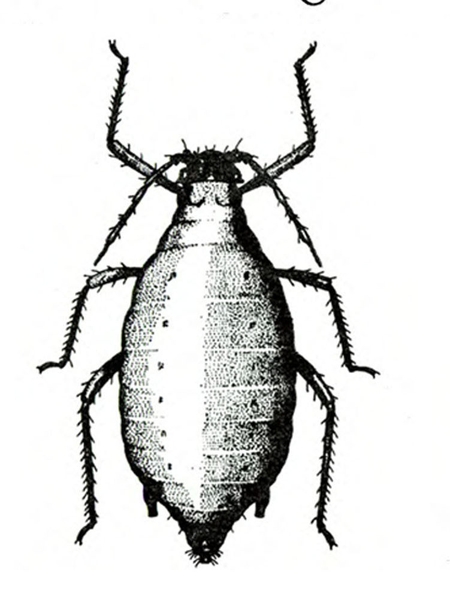

Corn Leaf Aphid

Rhopalosiphum maidis (Fitch), Aphididae, HEMIPTERA

Description

Adult—The oval, wingless adult is a little more than 1/16 inch long (Figure 15A). It is usually pale bluish-green with black antennae, legs, and cornicles and a dark area around the base of the cornicles. The head is marked with two dark, longitudinal bands, and the abdomen has a row of black spots on each side. The body often appears to have a powdery coating. The winged form is about the same size (Figure 15B).

Egg—It is thought that corn leaf aphids are among the few aphid species that do not lay eggs.

Nymph—Similar to the wingless adult, the nymph is smaller and also lacks wings (Figure 15C).

Biology

Distribution—The range of the corn leaf aphid extends throughout the tropical and temperate regions of the world. In the continental United States, it occurs in all areas except the Rocky Mountains region. It is rarely a problem in the northern states.

Host Plants—The corn leaf aphid prefers barley, sorghum, and corn, in that order. It also infests many other wild and cultivated grasses.

Damage—Colonies of feeding aphids cause mottling and discoloration of leaves. Heavily infested leaves turn red or yellow, shrivel, and die. The significant damage usually occurs during and after flowering, when the aphid population peaks and they feed on corn tassels and silks. The areas they attack become covered with sweet, sticky honeydew secretions. Black mold grows on the honeydew and may cause poor corn pollination, interfere with photosynthesis and, in severe cases, reduce grain development. Entomologists have speculated that the honeydew attracts corn earworm moths, inducing heavy deposition of earworm eggs.

Life History—Little is known about the biology of this pest in North Carolina. Because the relationship between corn and this aphid is not well understood, it has been difficult to estimate damage and determine population thresholds at which damage occurs. This aphid generally is not considered a serious threat. Corn leaf aphid adults overwinter each year in southern states, including North Carolina. On warm winter days, females continue to actively feed and reproduce on winter grain crops or other grasses. The first adults to appear in spring are winged females that fly in search of suitable host plants, sometimes migrating far northward. Shortly after, they give birth to live nymphs, which usually develop into wingless females. Under crowded conditions, more winged females develop and migrate. Males are rarely found, but females continue to reproduce without mating. Reproduction slows in winter and summer and is most rapid during fall and spring; therefore, corn leaf aphids tend to be a problem on winter grains in spring and on late-planted corn in fall. The number of generations per year varies from nine in Illinois to fifty in southern Texas.

Control

Infestations of corn leaf aphid usually are heaviest on late-planted corn; therefore, early planting and other cultural practices that hasten maturity help prevent aphid problems. Corn leaf aphids rarely require control in North Carolina because high temperatures and natural enemies reduce aphid populations in summer. Should damaging aphid populations develop, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Dusky Sap Beetle

Carpophilus lugubris Murray, Nitidulidae, COLEOPTERA

Description

Adult—This dark-gray or brown beetle is oblong to oval in shape and has club-like antennae (Figure 16A). It is between 1/8 and almost 3/16 inch long.

Egg—The white, sausage-shaped egg is pointed at one end. It is very small.

Larva—When mature, the yellowish or pinkish-white grub is almost 1/4 inch long. It has a translucent, spiny body with three pairs of short legs near its head (Figure 16B).

Pupa—The light-colored pupa is about the same size and shape as the adult and darkens as it matures.

Biology

Distribution—The dusky sap beetle occurs from Brazil to New York and westward to Arizona, Utah, and Washington. In the United States, it is particularly common along the Atlantic coast.

Host Plants—Besides corn, this beetle infests apple, peach, tomato, pea, and yucca. It is also attracted to various tree stumps, bark wounds that are oozing sap, acorns, Phylloxera galls, dropped fruit or nuts, and even corn seeds (Figure 16C).

Damage—Prior to 1950, dusky sap beetles were considered insignificant scavengers that posed no threat to sweet corn. Today they are recognized as secondary pests that usually become problems after corn is first damaged by other pests, such as the corn earworm. Dusky sap beetles are attracted to sweet corn as it tassels. They feed on ripening pollen and chew tassels. Later they move to leaf axils where pollen has fallen and collected. Should mature ears on the plant be damaged, dusky sap beetles eventually will oviposit (lay eggs) in the kernels. As a result, larvae contaminate the ears (Figure 16D).

Life History—Dusky sap beetles overwinter as adults in soil or debris near the bases of trees or stumps. Resuming activity in April or early May, they are attracted to tree wounds. About 13 days after emerging, first-generation females deposit eggs in decomposing plant material. Later generations often oviposit in silk channels or kernels of sweet corn. Larvae feed on whatever is available when they emerge and eventually pupate in the soil. In summer, 28 to 30 days elapse between egg deposition and adult emergence.

Dusky sap beetles are usually scarce in spring and increase in fall. In sweet corn, however, sap beetle populations continue to decline after tasseling (about June 15 in North Carolina). At least three or four generations occur each year. More generations are possible, especially if beetles develop in corn refuse.

Control

Control for this pest is primarily cultural. Plowing crop debris under destroys possible overwintering and breeding sites. Tight, long-husked corn varieties are more resistant to corn earworms and are therefore less likely to be infested by sap beetles. Varieties resistant to sap beetles include Country Gentleman, Golden Security, Tender Joy, Trucker's Favorite, Stowell's Evergreen, and Victory Golden. Though these varieties usually sustain less injury than susceptible varieties, they are not immune to attack.

An adequate spray program to control other corn ear pests should prevent dusky sap beetles from becoming a problem. For recommended insecticides and rates, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

European Corn Borer

Ostrinia nubilalis (Hübner), Pyralidae, LEPIDOPTERA

Description

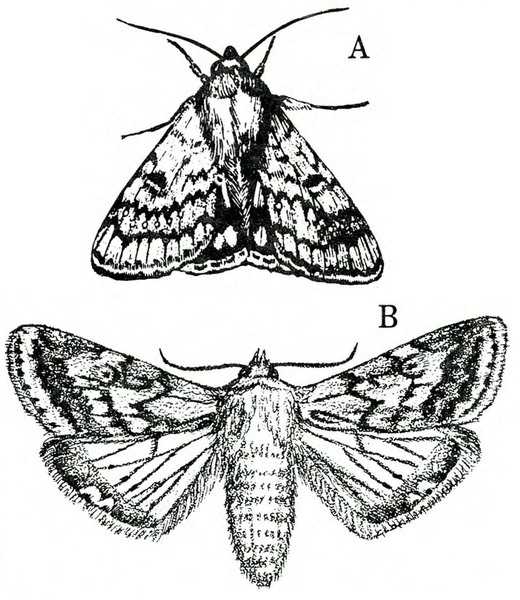

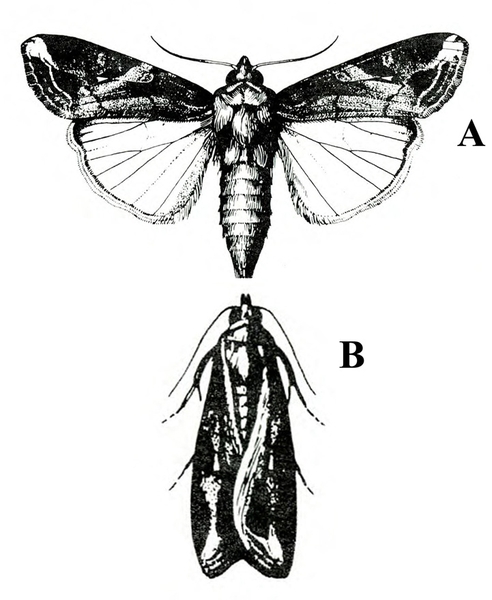

Adult—The female moth has a robust body and a wingspan of about 1 inch. The body is pale yellow to light brown. The outer third of the wings is usually crossed by dark, zigzag lines. The male moth is smaller, more slender, and darker than the female. The outer third of its wings is usually crossed by two zigzag streaks of pale yellow, and often there are pale-yellow areas on the forewings (Figure 17A–C).

Egg—Each white egg is about half the size of a pinhead. As the brown head of the borer inside becomes visible, the eggs change to pale yellow and darken just before hatching. Within the egg mass, the eggs overlap one another like fish scales. The masses of 20 to 30 eggs are covered with a shiny, waxy substance (Figure 17D).

Larva—The newly hatched larva, about 1/16 inch long, has a black head, five pairs of prolegs, and a pale-yellow body bearing several rows of small black or brown spots. It develops through five or six instars to become a fully grown larva about 1 inch long (Figure 17E).

Pupa—The brown pupa is 1/2 to almost 5/8 inch long with a smooth, capsule-like body (Figure 17F).

Biology

Distribution—Introduced into the United States from Europe in 1909, the European corn borer has spread throughout the contiguous United States and into Canada. In North Carolina, the largest populations of this pest occur in the coastal plain, where 75 percent of the stalks in some fields have been attacked. Forty percent lodging (stalk breakage) due to borers has been observed in the piedmont when harvesting has been delayed.

Host Plants—The European corn borer infests more than 200 plant species, but corn is a preferred host. Other vegetable crops likely to be injured include bean, beet, celery, potato, pepper, and tomato.

Damage—On most crops, borers begin feeding on the leaf surface. In corn, feeding occurs first in the whorl. Later, the larvae bore into midribs of leaves and inside the stalk. Frass and silk near entrance holes are evidence of their presence. Borers weaken stalks, or stems, and interfere with the movement of plant nutrients, reducing yields. On infested corn plants, tassels and stalks may break, ears drop, or developing ears remain small.

Life History—Mature larvae overwinter inside tunnels in stubble, stalks, ears, or other protective plant material. They pupate in spring. During April and May, adult moths emerge and mate. Each female lays 500 to 600 eggs in small masses of 20 to 30 on the undersides of leaves. Eggs hatch in three to twelve days (development is faster in warmer weather). Young larvae usually begin feeding on leaf surfaces. Two to three days later, larvae commence boring into midribs of the leaves, then into stalks or ears, continuing to tunnel and feed until pupation. In Florence, South Carolina, the European corn borer completes four generations per year and may do so in parts of North Carolina too—this would mean that eggs of the second generation are laid in mid- to late June, those of the third generation in late July, and those of the fourth generation in September. This last generation is not a threat to corn. First-generation European corn borers are a threat to potatoes, and the second and third generations are pests of other vegetables.

Control

Many natural parasites of the European corn borer exist in corn-growing areas, mainly flies and wasps that have been introduced from Europe. Lady beetles, predaceous mites, and downy woodpeckers also prey on borers. The bacterial insecticide Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) shows some promise for borer control. Controlling the European corn borer with chemicals is difficult because sprays are effective only during the two- to three-day period after eggs hatch and before larvae bore into stems. Therefore, growers must carefully scrutinize crops for the presence of moths and eggs. The emergence of the first moths can be monitored by using either light traps or screened cages. Treatments should begin seven to ten days after a moth flight or about five days after eggs are found. For recommended insecticides and rates, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Fall Armyworm

Spodoptera frugiperda (Smith), Noctuidae, LEPIDOPTERA

Description

Adult—The adult moth has a wingspan of about 1 1/2 inches. The hind wings are grayish white, and the front wings are dark gray and mottled with lighter and darker splotches. Each forewing has a noticeable whitish spot near the tip (Figure 18A–B).

Egg—Minute, light-gray eggs (Figure 18C–D) are laid in clusters and covered with fuzzy, grayish scales from the female’s body. Each egg becomes very dark just before hatching.

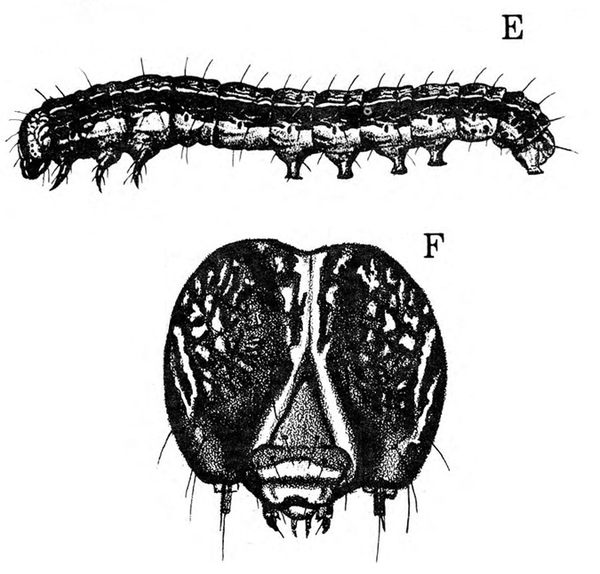

Larva—About 13/16 to 1 5/8 inches long, the fully grown larva varies in color from light tan or green to nearly black (Figure 18H). Along each side of its body is a longitudinal black stripe; down the middle of its back is a wider yellowish-gray stripe with four black dots on each segment. The head of the fall armyworm often is marked with a pale, but distinct, inverted Y (Figure 18E–F).

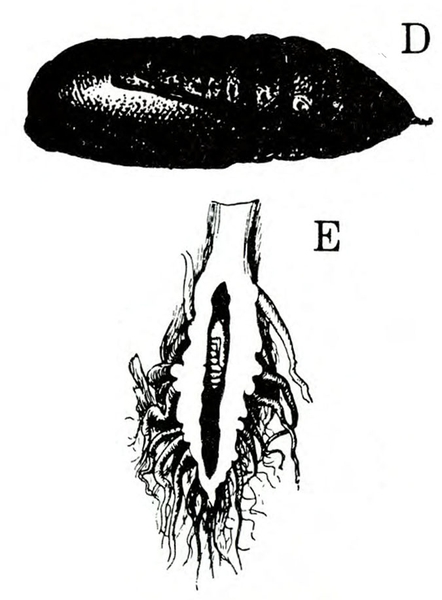

Pupa—The pupa, about 1/2 inch long, is at first reddish brown, darkening to black as it matures (Figure 18G).

Biology

Distribution—The fall armyworm is a permanent resident of the Gulf states, the tropics of North America, Central America, and South America, and parts of the West Indies. Each year, it migrates as far north as Montana, Michigan, and New Hampshire.

Host Plants—Sweet corn, field corn, sorghum, and grasses are preferred foods. The fall armyworm may also infest alfalfa, bean, peanut, potato, soybean, sweetpotato, turnip, spinach, tomato, cabbage, cucumber, cotton, tobacco, clover, and all grain crops.

Damage—The fall armyworm is the second most significant pest of sweet corn. It most frequently causes damage to the whorl of late, pre-tassel corn. Larvae feed throughout the tightly coiled blades, like corn earworms, causing shatterworm injury; when the blades unfurl, the new leaves are riddled with numerous ragged holes. Wet, tan excrement lodges in the remaining blades and blade axils. In addition to shatterworm injury, larval damage to corn may be threefold. First, larvae feed on the undeveloped tassels of young plants. Next, they attack immature ears near the shank. Finally, large larvae may bore into maturing ears and stalks.

Life History—Fall armyworms overwinter in Florida and along the Gulf Coast in several life stages, but usually as pupae. Egg-laying moths appear in North Carolina around mid-July. Each female lays about 1,000 eggs in masses of 50 to several hundred. Two to ten days later, the small larvae emerge, feed gregariously on the remains of the egg mass, and then scatter in search of food. They usually go unnoticed until they are about 1 to 1 1/2 inches long. By that time, if they are prolific enough, they have consumed so much foliage that growers may be alarmed. Larvae are most active early in the morning or late in the evening. When abundant, these caterpillars eat all the available food and then crawl in great armies to adjoining fields. After feeding for two or three weeks, the larvae dig about 3/4 inch into the ground to pupate. Within two weeks, a new swarm of moths emerges, usually flying several miles before laying eggs. Several generations may occur each year.

Control

Several parasitic enemies usually keep fall armyworm larvae at acceptably low levels, but cold, wet springs seem to reduce the effectiveness of these parasites, and armyworm populations often increase dramatically. Early planting is the most effective cultural control method in North Carolina. For recommended chemical controls, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Stalk Borer

Papaipema nebris (Guenée), Noctuidae, LEPIDOPTERA

Description

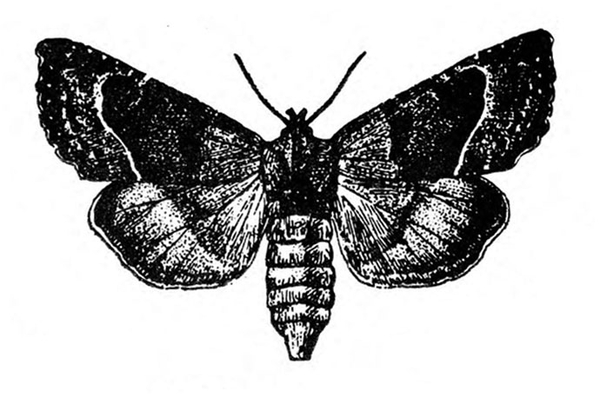

Adult—The forewings of this moth are basically reddish or grayish brown and marked with distinct, white spots or obscure, smoky areas. The outer third of each forewing is paler and bordered by a thin, white line. The hind wings are grayish brown on the upper surface and fawn gray below. The wingspan ranges from 1 to 1 5/8 inches (Figure 19A).

Egg—The longitudinally ribbed egg may be spherical or slightly flattened and measures 1/64 inch in diameter. White when first deposited, it gradually turns brownish gray or amber before hatching.

Larva—Early larval instars are brown with a dark-brown band around the middle and brown or purple longitudinal stripes on all but the first four segments (Figure 19G). The mature larva is solid white or light purple and may reach a length of 1 1/4 inches (Figure 19B–C).

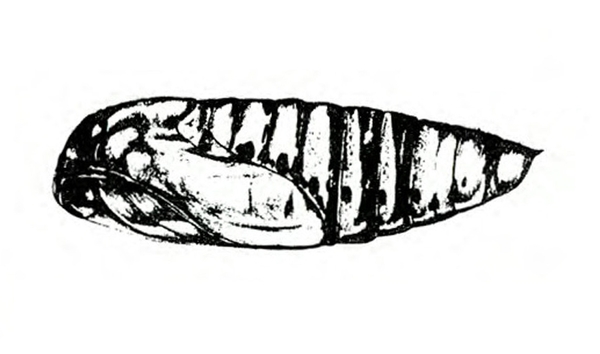

Pupa—The light-brown pupa gradually darkens as it matures and is about 5/8 to 3/4 inch in length (Figure 19D–E).

Biology

Distribution—The stalk borer occurs in all areas east of the Rocky Mountains from southern Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. Highest populations are associated with fields and fencerows with large-stemmed weeds. In North Carolina, economically damaging infestations are most common in the piedmont, particularly in no-till crops.

Host Plants—Stalk borers tunnel in almost any large-stemmed plant. Their hosts include at least 44 families and 176 species of plants. Besides corn, cultivated crops subject to infestation include cotton, potato, tomato, alfalfa, rye, barley, pepper, spinach, beet, and sugar beet. Among the many weedy plants infested, giant ragweed is the preferred host.

Damage—Stalk borers migrating from another host infest corn seedlings that are 2 inches to 2 feet tall, causing two types of injury. Larvae that enter the plant through the lower stalk tunnel upward, severing the leaves from below; when this happens, infested stalks are hollow, and apparently healthy green leaves wilt and die (Figure 19F). Other larvae climb plants, enter from the top, and feed on buds and rolled leaves. As new leaves unfurl, ragged holes are revealed that increase in size as leaves develop. Both forms of injury destroy tassels, promote suckering, and deform the upper plant. Soon after borers enter the seedlings, the stems often break. Frass is usually evident around the bases of more mature infested plants. After the whorl stage, corn is somewhat resistant to stalk borer and recovers more readily from damage. Damage is sporadic but most commonly associated with border rows of conventionally planted corn and with no-till plantings.

Life History—Stalk borers overwinter as eggs on weedy plants. In May, newly emerged larvae feed like leafminers on broadleaf plants or bore into grass stems. On all hosts, larvae eventually bore into stems and feed until they kill or outgrow their host; when this happens, larvae emerge at night from the plant they have outgrown and tunnel into another plant, including seedling corn. Developing through seven to sixteen instars, stalk borers mature in the second plant they infest. Late in July, borers leave the second host, dig into the soil, and construct individual cells in which they pupate. After a four-week pupal period, stalk borer moths emerge from their pupae, mate, and deposit eggs singly or in masses between the leaf sheath and stems of a weedy plant, where the eggs remain until the following spring. One generation occurs each year.

Control

Stalk borers cannot be controlled once they have entered the plant; therefore, control measures are strictly preventive. Destroying weeds in fields and along fencerows eliminates many primary hosts from which the borers migrate to infest corn.

Other Resources

General

Brett, C. H. The Use of Resistant Varieties and Other Cultural Practices for Control of Sweet Corn Insects in North Carolina. Bulletin 434. North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station, 1970.

Harris, Jr., E. D. Corn Earworm and Fall Armyworm Control on Sweet Corn. Leaflet 80. University of Georgia Cooperative Extension Service, 1973.

Kelshimer, E. G., N. C. Hayslip, and J. W. Wilson. Control of Budworms, Earworms, and Other Insects Attacking Sweet Corn and Green Corn in Florida. Bulletin 466. Florida Agricultural Experiment Station, 1950.

Corn Earworm

Barber, G. W. The Corn Earworm in Southeastern Georgia. Bulletin 192. Georgia Agricultural Experiment Station, 1936.

Blanchard, R. A., and W. A. Douglas. The Corn Earworm as an Enemy of Field Corn in the Eastern States. Farmers' Bulletin 1651. USDA, 1953.

Brannon, L. W. Control of the Corn Earworm on Fordhook Lima Beans in Eastern Virginia. Circular 506. USDA, 1939.

Ditman, L. P., and E. N. Cory. “The Corn Earworm—Biology and Control.” University of Maryland Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 328 (1931): 443–82.

Eden, W. C., and H. Yates. Corn Earworm Control on Sweet Corn in Alabama. Bulletin 326. Auburn University Agricultural Experiment Station, 1960.

Neunzig H. H. “Wild Host Plants of the Corn Earworm and the Tobacco Budworm in Eastern North Carolina.” Journal of Economic Entomology 56 (1963): 135–39.

Neunzig H. H. “The Eggs and Early-Instar Larvae of Heliothis zea and Heliothis virescens (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae).” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 57 (1969): 98–102.

Neunzig H. H. The Biology of the Tobacco Budworm and the Corn Earworm in North Carolina with Particular Reference to Tobacco as a Host. Technical Bulletin 196. North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station, 1969.

USDA. The Corn Earworm in Sweet Corn: How to Control It. Leaflet 411. USDA, 1967.

Wendell, J., and W. W. Copland. “Distribution and Abundance of the Corn Earworm in the United States.” USDA Cooperative Economic Insect Report 21 (1971): 71–76.

Corn Flea Beetle

Turner, R. Threat of Corn Flea Beetle Moderate to Severe in Ohio this Spring, Slightly Higher Potential for Stewart’s Bacterial Wilt. College of Food, Agricultural, and Environmental Sciences, Ohio State University, 2013.

Corn Leaf Aphid

Cartier, J. J. “On the Biology of the Corn Leaf Aphid.” Journal of Economic Entomology 50 (1957): 110–12.

Everly, R. T. “Loss in Corn Yield Associated with the Abundance of the Corn Leaf Aphid, Rhopalosiphum maidis, in Indiana.” Journal of Economic Entomology 53 (1960): 924–32.

Gesell, S., and D. Calvin. Corn Leaf Aphid on Field Corn. PennState Extension, 1983.

Walter, E. B. “Differential Susceptibility of Corn Hybrids to Aphis maidis.” Journal of Economic Entomology 33 (1940): 623–34.

Wildermuth, V. L., and E. V. Walter. Biology and Control of the Corn Leaf Aphid with Special References to the Southwestern States. Technical Bulletin 306. USDA, 1932.

Dusky Sap Beetle

Connell, W. A. Nitidulidae of Delaware. Technical Bulletin 318. Delaware Agricultural Experiment Station, 1956.

Daugherty, D. M., and C. H. Brett. Nitidulidae Associated with Sweet Corn in North Carolina. Technical Bulletin 171. North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station, 1966.

Harrison, E. R. “Infestation of Sweet Corn by the Dusky Sap Beetle, Carpophilus lugubris.” Journal of Economic Entomology 55 (1962): 922–25.

Parson, C. T. “A Revision of Nearctic Nitidulidae (Coleoptera).” Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard 92 (1943): 119–278.

Sanford, J. W., and W. H. Luckmann. “Observations on the Biology and Control of the Dusky Sap Beetle in Illinois.” Proceedings, North Central Branch Entomological Society of America 18 (1963): 39–43.

Yero, R. J. “The Biology and Control of Carpophilus lugubris in Sweet Corn.” Proceedings, North Central Branch Entomological Society of America 12 (1957): 46–47.

European Corn Borer

Capinera, J. L. Common Name: European Corn Borer, Scientific Name: Ostrinia nubilalis (Hübner) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Featured Creatures. Publication Number: EENY–156. Entomology and Nematology, FDACS/DPI, EDIS, University of Florida, 2020.

Durant, J. A. “Seasonal History of the European Corn Borer at Florence, South Carolina.” Journal of Economic Entomology 62 (1969): 1071–75.

Mead, F. W. European Corn Borer, Ostrinia nubilalis (Hübner), Detection Methods (Lepidoptera: Pyraustidae). Entomology Circular 122. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry, 1972.

Sparks, A. N., and J. R. Young. “European Corn Borer Activity in Georgia.” Journal of the Georgia Entomological Society 6, no. 4 (1971): 211–15.

USDA. The European Corn Borer—How to Control It. Farmers' Bulletin 2190. USDA, 1967.

Fall Armyworm

Harrell, E. A., J. R. Young, and W. W. Hard. “Insect (Spodoptem fugiperda) Control on Late Planted Sweet Corn.” Journal of Economic Entomology 70 (1977): 129–31.

Luginbill, P. The Fall Armyworm. Technical Bulletin 34. USDA, 1928.

USDA. The Armyworm and the Fall Armyworm—How to Control Them. Leaflet 494. USDA, 1961.

Stalk Borer

Decker, G. O. “The Biology of the Stalk Borer Papaipema nebris (Gn.).” Iowa State Agricultural Experiment Station Research Bulletin 143 (1931): 292–351.

Hamilton, C. C. The Stalk Borer (Papaipema nebris Gn.). Circular 342. New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station, 1935.

Publication date: June 14, 2024

AG-295

Other Publications in Insect and Related Pests of Vegetables

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.