Because carrots are root crops, soil-inhabiting pests such as the southern potato wireworm and vegetable weevil have the most direct effect on produce quality. Armyworms, however, may cause indirect injury to the taproot by cutting stems or consuming aboveground foliage. Few other insect problems are common with carrots in North Carolina.

A. Chewing insects that cut holes or entire leaves

- Caterpillars with three pairs of legs and five pairs of prolegs

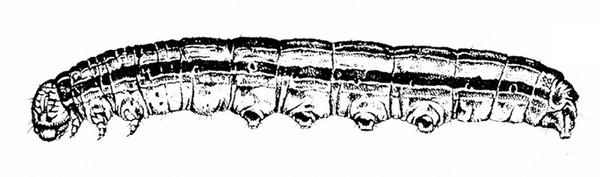

- Armyworm—This pale-green to yellowish- or brownish-green, smooth-bodied caterpillar measures up to 1 3/8 inches long. It has three dark, longitudinal stripes and a tan or greenish-brown head mottled with darker brown (Figure 1). Armyworms feed primarily at night on foliage and succulent stems.

- Parsleyworm—This yellowish-green caterpillar may be up to 1 5/8 inches long and has transverse black bands and deep-yellow or orange spots. The head is greenish yellow with black stripes (Figure 2). When disturbed, a V-shaped scent organ protrudes from behind the head. Parsleyworms feed during the day.

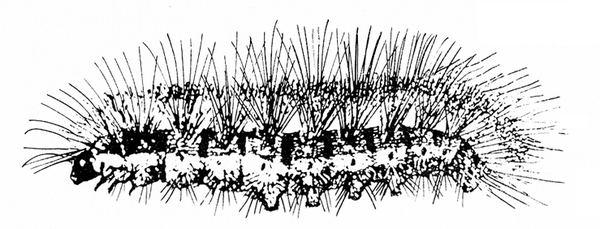

- Yellow woollybear—This caterpillar is white to yellow or brown or red and has dense, white hairs covering its body (Figure 3). Young larvae feed in colonies on the undersides of leaves; older larvae disperse and feed on all plant parts except the root.

- Vegetable leafminer—These bright-yellow maggots grow up to 1/8 inch long. They make S-shaped mines in leaves that are often enlarged at one end (Figure 4). Heavily infested leaves sometimes turn brown. (For more information about vegetable leafminers, see “Pests of Tomato.”)

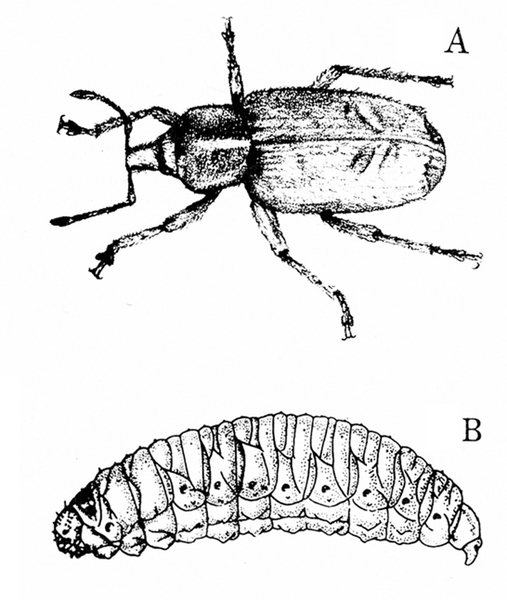

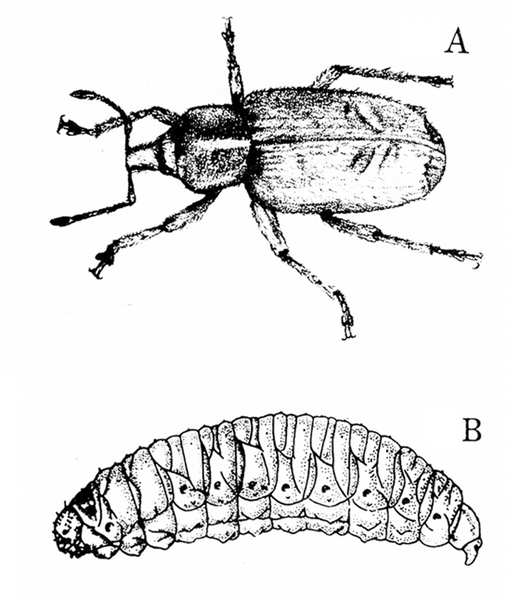

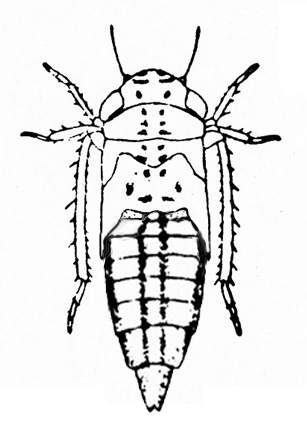

- Vegetable weevil and larva—This dull, grayish-brown weevil has a short, stout snout and light, V-shaped marks on its wing covers. The adult is about 1/4 inch long, and the larva grows to 9/16 inch long (Figure 5A–B). The legless larva is pale green and has a dark, mottled head. Adults and larvae feed primarily at night on buds and foliage. (For more information about vegetable weevils, see “Pests of Crucifers.”)

B. Insects with needlelike mouthparts that cause foliage to become yellowed or distorted

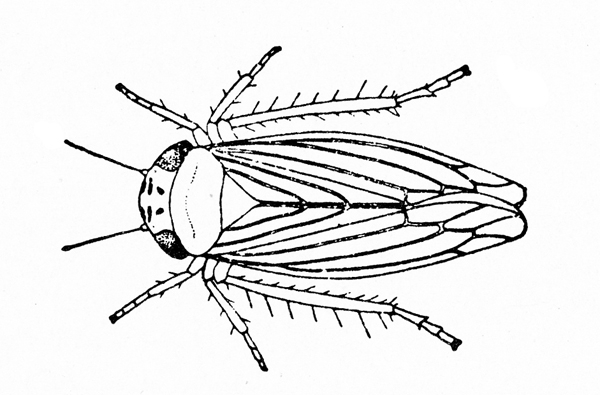

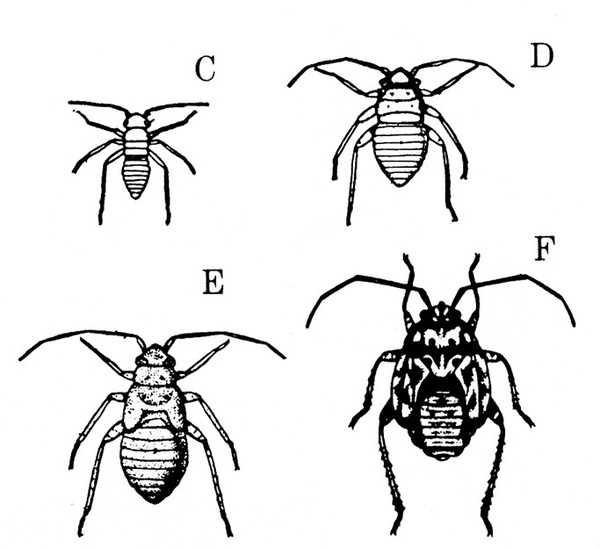

- Aster leafhopper —Up to 3/16 inch long, aster leafhoppers are yellowish green and have six black spots on the front of the head (Figure 6). Nymphs are sometimes light brown instead of yellow or green. Adults and nymphs cause pale spots on the tops of leaves.

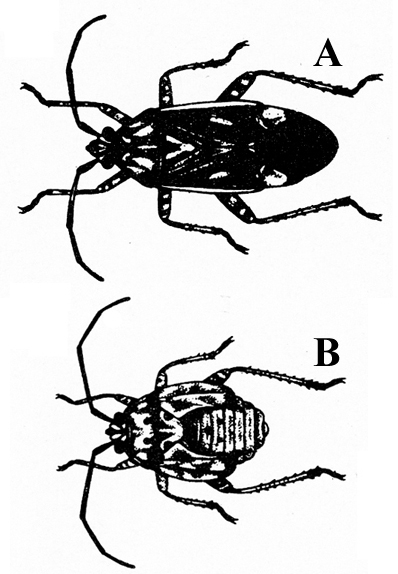

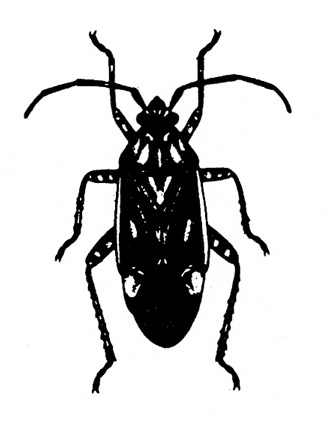

- Tarnished plant bug—These oval-shaped brown bugs (Figure 7A–B) are up to 1/4 inch long and have long legs, long antennae, and a white triangle between the “shoulders.” Nymphs are 1/16 to almost 1/4 inch long and are yellowish-green to green with black spots on the back. New plant growth may be disfigured by tiny spots of excrement and is often yellowed and distorted, causing plants to appear unthrifty.

C. Insects that feed on underground plant parts

- Vegetable weevil and larva—Previously described, these weevils and their larvae (Figure 8A–B) often attack large taproots, which ruins the commercial value of the damaged carrots. (For more information about vegetable weevils, see “Pests of Crucifers.”)

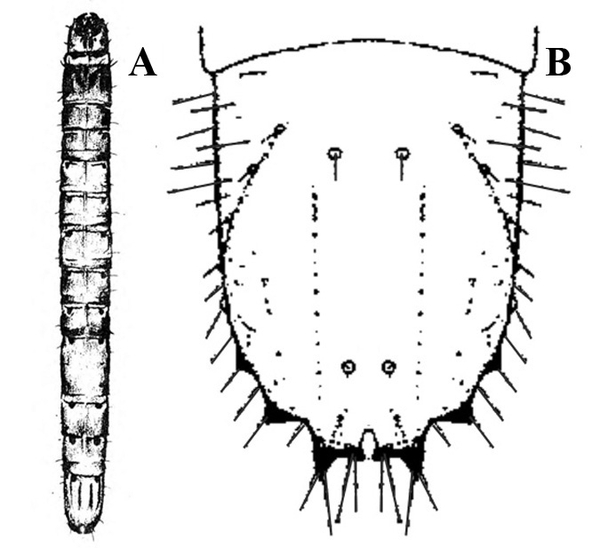

- Southern potato wireworm—These slender, wirelike, cylindrical larvae have three pairs of short legs and a pair of fleshy anal prolegs. The white, cream, or yellow-gray larvae have red-orange heads and grow to 11/16 inch long. The last abdominal segment has a closed oval notch (Figure 9A–B). These wireworms chew irregular holes in infested taproots. (For more information about southern potato wireworms, see “Pests of Potato.”)

Armyworm

Mythimna unipuncta (Haworth), Noctuidae, LEPIDOPTERA

Description

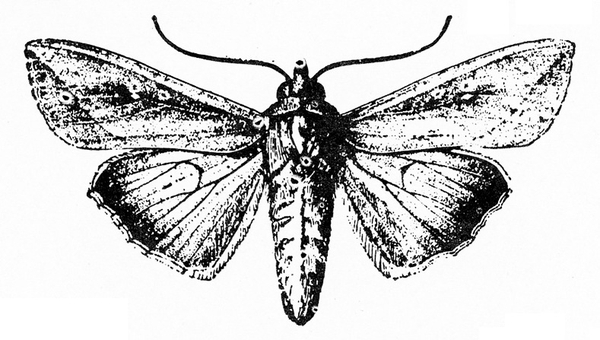

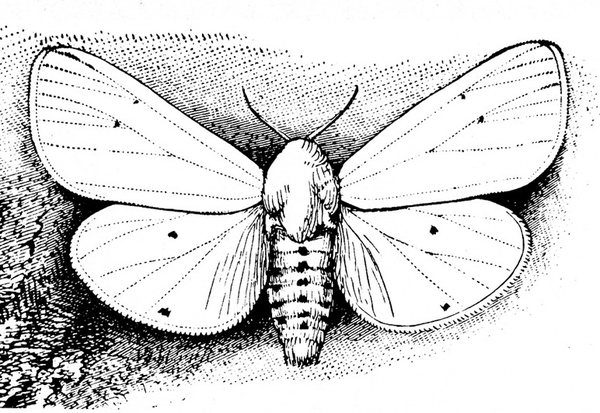

Adult—The armyworm moth has grayish-brown forewings, each with a white spot near the center, and grayish-white hind wings (Figure 10A). The wingspan averages 1 1/2 inches.

Egg—The minute, greenish-white egg is globular in shape.

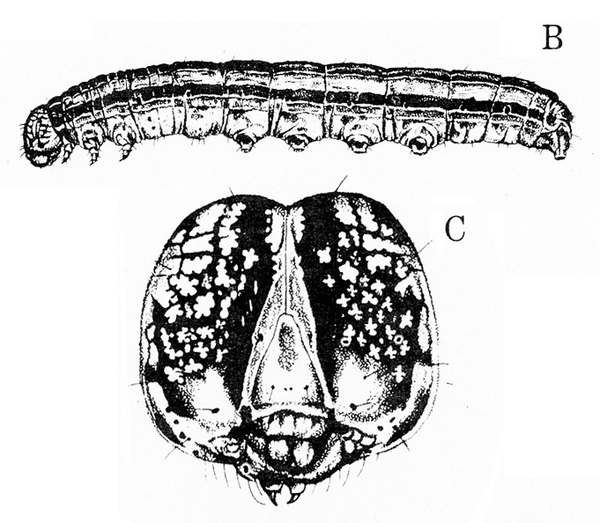

Larva—The young armyworm is pale green. The mature larva is yellowish or brownish green with a tan or greenish-brown head that is mottled with darker brown. The smooth, practically hairless body is marked with three dark, longitudinal stripes, one along each side and one down the back (Figure 10B–C). A full-grown armyworm is 1 5/16 to 1 3/8 inches long.

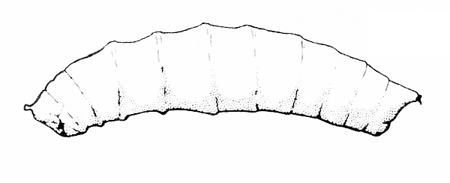

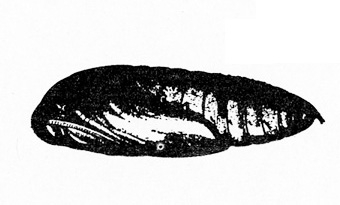

Pupa—The 1/2-inch-long pupa is reddish brown and darkens gradually until it is almost black (Figure 10D).

Biology

Distribution—Armyworms occur throughout the United States east of the Rocky Mountains. In North Carolina, they are particularly abundant in the piedmont and coastal plain. During daytime, larvae usually remain under litter on the ground.

Host Plants—Although armyworms strongly prefer grasses and cereals, they have occasionally been reported to infest various vegetables, fruits, legumes, and weeds, especially when they are "on the march.” When they exhaust a food supply, the worms migrate as one "army" to new host plants. Fields adjacent to or harboring lush grass are most commonly attacked. Besides carrot, some of their vegetable host plants include bean, beet, cabbage, cauliflower, corn, cucumber, lettuce, onion, pea, pepper, radish, and sweetpotato.

Damage—Preferring to feed at night, armyworms devour succulent foliage. By feeding on leaves and occasionally stems, they can severely damage seedling stands. Because they feed in darkness, armyworms may inflict much injury before they are detected.

Life History—Armyworms overwinter as partially grown larvae. Early in spring, larvae resume feeding at night, usually on grasses and small grains. First-generation adults appear in May during warm springs or later in June in cool springs. Moths mate soon after emergence and feed on nectar for seven to ten days. Females then deposit up to 2,000 eggs in small clusters or rows on the leaf sheaths of grasses. Larvae emerge in six to twenty days. After feeding for three or four weeks, they drop to the ground and pupate in earthen cells 2 to 3 inches deep within the soil. Moths emerge two to four weeks later. Armyworms complete five or more generations per year in North Carolina.

Control

Parasites, various diseases, insect predators, and birds usually keep armyworms under control, except after cold, wet springs. When practical, cultural methods such as disking large areas can help reduce future armyworm populations by exposing the pupae to natural enemies and hot weather. Armyworm moths are strong flyers, however, and carrots are likely to be reinfested. Because armyworms are not resistant to pesticides, they can be readily controlled chemically when numbers increase. For specific chemical control measures, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Aster Leafhopper

Macrosteles fascifrons (Stål), Cicadellidae, HEMIPTERA

Description

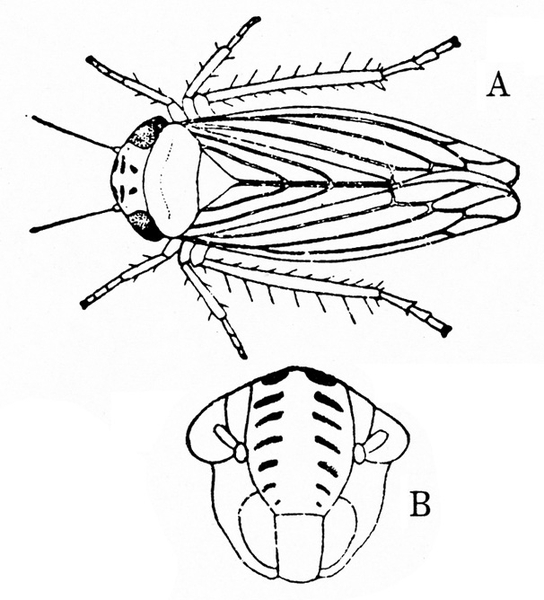

Adult—This light-colored, smoky-green to yellowish-green leafhopper may be as short as 1/16 inch or as long as 3/16 inch. Sometimes called the six-spotted leafhopper, this species has six black spots arranged in pairs on the front of the head (Figure 11A–B).

Egg—No description is available in the literature.

Nymph—The nymph is 1/64 to 1/8 inch long. It has the same head markings as the adult but varies in color from yellow or light brown to a pale greenish-gray (Figure 11C).

Biology

Distribution—During the growing season, aster leafhoppers can be found from Mexico to Alaska. Habitats as varied as grasslands, swamps, and dry prairies can support populations of these insects.

Host Plants—Aster leafhoppers attack a wide range of vegetables, fruits, herbs, grasses, and weeds. Besides carrot, some common vegetable and herb hosts include lettuce, celery, parsnip, parsley, dill, onion, shallot, pepper, tomato, cucumber, and sweet corn.

Damage—Nymphs extract plant sap from the undersides of leaves and cause a general yellowing of plant foliage. Adults damage plants by transmitting diseases such as aster yellows virus to carrot, lettuce, and aster. Aster leafhoppers are the only known vector of this disease in the eastern United States. Infected plants turn yellow, become stunted, branch excessively, and develop short internodes. Aster yellows virus mostly affects young plants.

Life History—The biology of the aster leafhopper has been studied primarily in northern states and in the laboratory but not in North Carolina. Here, it is believed to overwinter on perennial weeds or fall-planted small grains, probably both as eggs and adults. In spring, adults migrate to other herbaceous host plants. They pick up the aster yellows virus by feeding on infected plants but cannot transmit it until after an incubation period that lasts 10 to 18 days. Viruses are usually transmitted by adult leafhoppers because nymphs molt fairly often and mature into adults in about 18 days (under lab conditions). Thus, the virus often does not have enough time to incubate in nymphs. Adults, excluding overwintering forms, have been reported to live an average of 42 days on host plants in the laboratory. Life cycles as short as 20 days occur in summer in Michigan. Many generations per year are possible in North Carolina.

Control

Aster leafhoppers and aster yellows virus are rarely a problem in North Carolina. Should large pest populations develop, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual for control recommendations.

Parsleyworm/Black Swallowtail Butterfly

Papilio polyxenes Stoll, Papilionidae, LEPIDOPTERA

Description

Adult—The black swallowtail butterfly varies in size and coloration. The female is slightly larger and darker than the male. Both sexes appear velvety-black and have hind wings with tails and peacock-like eyespots (Figure 12A). Some individuals, especially males, have bands of yellow spots across the wings. The wingspan may be as wide as 3 inches across.

Egg—Spherical and almost 1/16 inch in diameter, the egg gradually changes from pale yellow to reddish brown (Figure 12B).

Larva—When fully grown, the parsleyworm is about 1 5/8 inches long. Its yellowish-green body has transverse black bands and deep-yellow or orange spots on these black areas (Figure 12C). Behind the caterpillar’s yellowish-green, black-striped head is a pair of yellow or red scent organs that protrude like horns when the insect is disturbed. Early-instar larvae resemble mature larvae in coloration but may have spines.

Pupa—Known as a chrysalis, the sharply angled pupa is dull gray and mottled with black and brown. It is about 1 1/4 inches long (Figure 12D).

Biology

Distribution—This insect occurs from southern Canada into Florida and westward to the Rocky Mountains. It has also been reported in Arizona, New Mexico, and Mexico.

Host Plants—Besides carrot, parsleyworms feed primarily on celery, parsley, parsnip, dill, and other closely related herbs and weeds.

Damage—Though they feed on foliage, parsleyworms are not usually serious pests. They usually eat leaves, but occasionally attack blossoms and underdeveloped seeds. Even at low densities, they are often conspicuous because of their striking appearance. These caterpillars, however, do little damage to plants and do not sting or attack people.

Life History—Parsleyworms overwinter as pupae (chrysalides) attached to stems or fallen leaves. Black swallowtail butterflies emerge in April or early May. Soon afterward, females deposit eggs on plant foliage. Eggs hatch four to nine days later, and the young larvae begin feeding on leaves. The period of larval development varies by geographic location but rarely lasts longer than four weeks. Mature larvae become chrysalides and are attached to host plants by silken threads. Butterflies emerge from these nonoverwintering pupae in nine to fifteen days. The number of annual generations varies from two in northern states to three in parts of the Midwest to four in the Gulf states. There are probably three generations per year in North Carolina.

Control

Since parsleyworms are highly visible and pose so small a threat, handpicking these caterpillars from plants is the best method of controlling them. For control recommendations in commercial production, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Tarnished Plant Bug

Lygus lineolaris (Palisot de Beauvois), Miridae, HEMIPTERA

Description

Adult—Like most bugs in the genus Lygus, the tarnished plant bug is oval and has a characteristic white triangle between the "shoulders" (Figure 13A). Its legs and antennae are relatively long. Adults may be different shades of brown and are about 1/4 inch long.

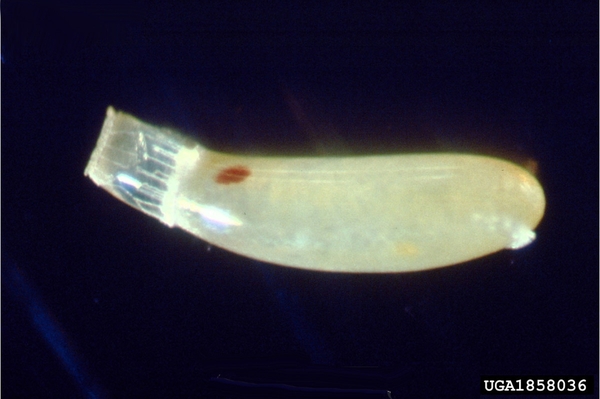

Egg—The tiny, elongate egg is slightly curved (Figure 13B).

Nymph—The wingless nymph is yellow-green to green in color with several black spots on its back. Length varies from 1/16 inch to slightly smaller than the adult (Figure 13C–F). The fourth instar nymph has wing pads.

Biology

Distribution—Warm, dry climates are most conducive to infestations. Tarnished plant bugs pose a limited threat in North Carolina. In states farther south and southwest, economic injury occurs annually.

Host Plants—Tarnished plant bugs infest more than 50 economically important plants, including many field, forage, fruit, and vegetable crops. Weeds such as butterweed, fleabane, goldenrod, aster, vetch, dock, and dogfennel commonly harbor these insects in southern states.

Damage—Shiny, circular spots of excrement on various plant parts indicate the presence of tarnished plant bugs. These bugs pierce buds and terminal growth with their needlelike mouthparts and extract plant juices. New growth may be yellowed and distorted, causing plants to appear unthrifty.

Life History—In North Carolina, adults hibernate in plant debris and resume activity in spring, when females insert eggs into succulent host-plant tissue with their swordlike ovipositor. Eggs hatch ten days to three weeks later. The nymphs develop through five instars over a three-week period as they feed on plant sap. Mature nymphs molt and emerge as adults. The first few generations develop on preferred hosts that include small grains, alfalfa, wild grasses, vetch, dock, and fleabane. As hay is cut or as other plants dry out, tarnished plant bugs migrate in large numbers to succulent hosts such as cotton or vegetable crops. During summer, the life cycle (from egg hatching to adult emergence) is completed in four weeks. As many as five annual generations are possible.

Control

If planted as far as possible from the forage and cotton crops preferred by this pest, vegetable crops are not likely to be heavily damaged. Weed control and destruction of crop residue help eliminate sources of food and shelter for the tarnished plant bug. Chemical control should not be necessary; in the case of heavy infestations, however, consult the recommendations in the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Yellow Woollybear

Spilosoma virginica (Fabricius), Arctiidae, LEPIDOPTERA

Description

Adult—With a wingspan of nearly 1 5/8 inches, this moth is nearly pure white except for the abdomen, which has two orange stripes and three rows of black dots. Most moths have a few black spots on each wing (Figure 14A).

Egg—The white to golden-yellow spherical eggs are laid in clusters of 50 to 60 and are usually covered with hairs from the body of the moth. Individual eggs are about 1/32 inch in diameter.

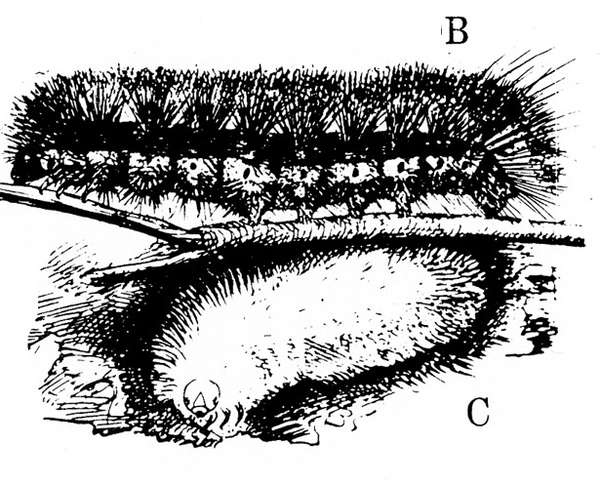

Larva—Densely clothed with long and short hairs, the yellow woollybear caterpillar may be pale yellow, brownish yellow, red, or white (Figure 14B–C). It usually blackens in color near the head. A fully grown caterpillar may be as long as 2 inches.

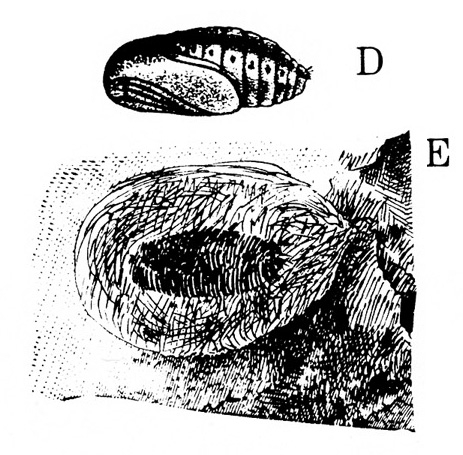

Pupa—About 5/8 inch long, the reddish-brown pupa is enveloped by a thin, fragile, silken cocoon (Figure 14D–E).

Biology

Distribution—The yellow woollybear is common throughout North America.

Host Plants—Yellow woollybear caterpillars feed on a wide range of garden, field, and ornamental crops as well as weeds. Besides carrot, vegetable hosts may include asparagus, bean, beet, cabbage, cauliflower, celery, corn, eggplant, onion, parsnip, pea, potato, pumpkin, radish, rhubarb, salsify, squash, sweetpotato, and turnip.

Damage—All stages of the foliage-feeding caterpillar consume flowers, leaves, tender stems, and fruit buds, primarily in summer and fall. Plants may be skeletonized by heavy infestations.

Life History—This insect overwinters in the pupal stage. Cocoons are often found in large numbers beneath a single shelter (for example, an old board or piece of tree bark). In spring, moths emerge and mate. Females soon deposit clusters of eggs on leaves. The eggs hatch after about seven days.

Young larvae feed in colonies on the undersides of leaves. As they mature, caterpillars disperse and feed on more exposed sites. After feeding for about four weeks, yellow woollybears are fully grown and begin to seek sheltered places in which to pupate. There, caterpillars spin cocoons and spend the next one to two weeks transforming into moths. The life cycle is then repeated. Several generations are completed each year.

Control

Several natural enemies limit yellow woollybear populations. Eggs are parasitized by Trichogramma wasps, and the caterpillars are susceptible to diseases caused by Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) bacteria and granulosis virus. This insect usually does not become a problem on crops that are being sprayed for other pests. Should an infestation develop, consult recommendations in the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Other Resources

Armyworm

Walton, W. R., and C. M. Packard. The Armyworm and Its Control. Farmers' Bulletin 1850. USDA, 1951.

Aster Leafhopper

Beirne, B. P. “The Nearctic Species of Macrosteles (Homoptera: Cicadellidae).” The Canadian Entomologist 84 (1952): 208–32.

Cress, D., and A. Wells. Celery and Carrot Insect Pests. Agricultural Extension Bulletin E-970. Michigan State University, 1977.

Dorst, H. E. A Revision of the Leafhoppers of the Macrosteles Group (Cicadula of Authors) in America North of Mexico. Miscellaneous Publication No. 271. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1937.

Hou, R. F., and M. A. Brooks. “Continuous Rearing of the Aster Leafhopper, Macrosteles fascifrons, on a Chemically Defined Diet.” Journal of Insect Physiology 21 (1975): 1481–83.

Miller, L. A., and A. J. Delyzer. “A Progress Report on Studies of Biology and Ecology of the Six-Spotted Leafhopper, Macrosteles fascifrons (Stål) in Southwestern Ontario.” Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Ontario 90 (1960): 7–13.

Wallis, R. L. Host Plants of the Six-Spotted Leafhopper and the Aster Yellows Virus and Other Vectors of the Virus. ARS-33-55. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 1960.

Wallis, R. L. “Host Plant Preference of the Six-Spotted Leafhopper.” Journal of Economic Entomology 55 (1962): 998–99.

Parsleyworm

Chittenden, F. H. “Some Insects Injurious to Truck Crops. II. The Celery Caterpillar.” USDA Entomology Bulletin 82 (1909): 20–24.

Erickson, J. M. “The Comparative Utilization of Cultivated and Weedy Umbellifer Species by Larvae of the Black Swallowtail Butterfly, Papilio polyxenes.” Psyche 82 (1975): 109–30.

Erickson, J. M., and P. Feeny. “Sinigrin: A Chemical Barrier to the Black Swallowtail Butterfly, Papilio polyxenes.” Ecology 55 (1974): 103–11.

Hall, D. W. Common Name: Eastern Black Swallowtail, Scientific Name: Papilio polyxenes asterius (Stoll) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Papilionidae). Featured Creatures. Publication Number: EENY–504. Entomology and Nematology, FDACS/DPI, University of Florida, 2011.

Tarnished Plant Bug

Kelton, L. A. “The Lygus Bugs of North America.” The Memoirs of the Entomological Society of Canada 107, Supplement S95 (1975): 5–101.

Pack, T. M., and P. Tugwell. Clouded and Tarnished Plant Bugs on Cotton: A Comparison of Injury Symptoms and Damage on Fruit Parts. Report Series 226. Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Arkansas, 1976.

Sevacherian, V., and V. M. Stern. “Host Plant Preferences of Lygus Bugs on Alfalfa— Interplanted Cotton Fields.” Environmental Entomology 3 (1974): 761–66.

Tugwell, N. P. “Plant Bugs in Northeast Arkansas.” Arkansas Farm Research 18 (1969): 10.

Tugwell, P., S. C. Young, B. A. Dumas, and J. R. Phillips. Plant Bugs in Cotton: Importance of Infestation Time, Types of Cotton Injury, and Significance of Wild Hosts Near Cotton. Report Series 227. Arkansas Agriculture Experiment Station, University of Arkansas, 1976.

Yellow Woollybear

Boucias, D. G., and G. L. Nordin. “A Granulosis Virus from Diacrisia virginica (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae).” Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 30 (1977): 434–35.

March, H. O. “Biological and Economic Notes on the Yellow-Bear Caterpillar (Diacrisia virginica Fab.).” USDA Bureau of Entomology Bulletin 82, Part V (1910): 59–66.

Publication date: June 11, 2024

AG-295

Other Publications in Insect and Related Pests of Vegetables

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.