Urban landscapes comprise an increasing percentage of potential wildlife habitat. With proper management and hard work, these areas provide valuable space for many wildlife species, especially birds.

The Basics

Along with spring’s wildflowers and pleasant weather come the joyous sounds of North Carolina’s migrating songbirds. From early April to mid-May, buntings, cuckoos, flycatchers, orioles, tanagers, thrushes, vireos, and warblers migrate from tropical countries in Central and South America and the Caribbean north to their breeding grounds in the United States (Figure 1a). These birds are called neotropical migrants. Many of these migrant songbirds stay in North Carolina to build their nests and raise their young, while others continue farther north to other breeding areas. These same migrant birds fly south in September and early October to avoid the food shortages that occur as temperatures get colder. Our more familiar yard birds, such as bluebirds, cardinals, chickadees, robins, and woodpeckers, don’t migrate to the tropics and are termed residents because they generally remain in North Carolina year-round (Figure 1b).

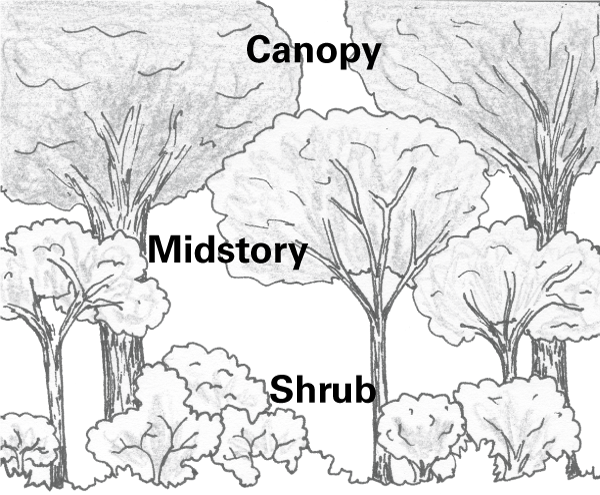

Birds are adapted to the native plants around them and should receive all life requirements from a properly organized suite of native vegetation. Native plants do not present the problems, such as unabated growth, that often arise with establishment of non-native plant species, and they are more likely to provide the food and cover that native birds need. It is important to provide a variety of different types of native plants in any bird habitat. Because different species of plants produce flowers, fruits, or seeds during different seasons of the year, the presence of a variety of plants ensures that food is available to birds year-round (Figure 2). Additionally, the presence of short and tall plants within the same general area provides the vertical vegetation structure that allows ground-dwelling, shrub-dwelling, and treetop birds to exist in the same horizontal space (Figure 3a, Figure 3b, and Figure 3c).

Backyard Management

Birds have three main requirements in life—food, water, and cover—which should be met through proper management of the backyard habitat.

Native Foods

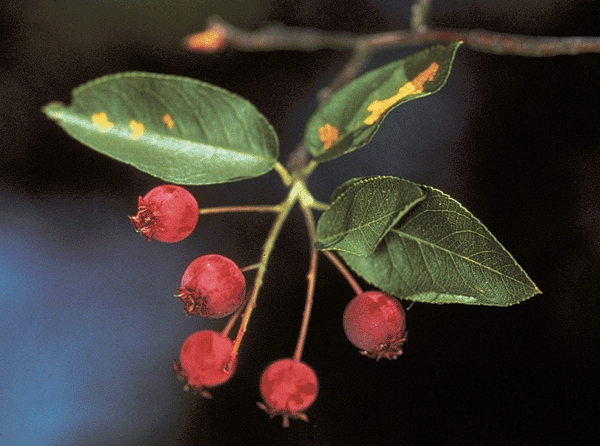

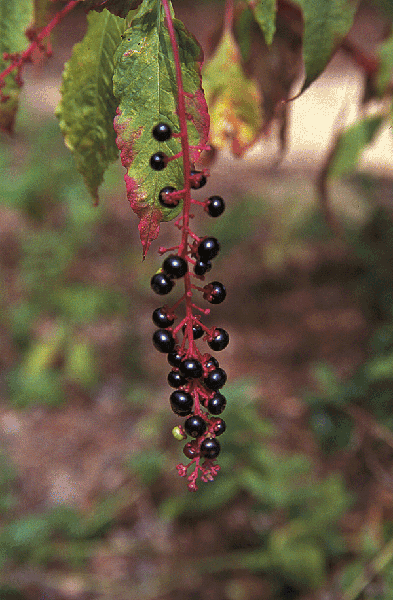

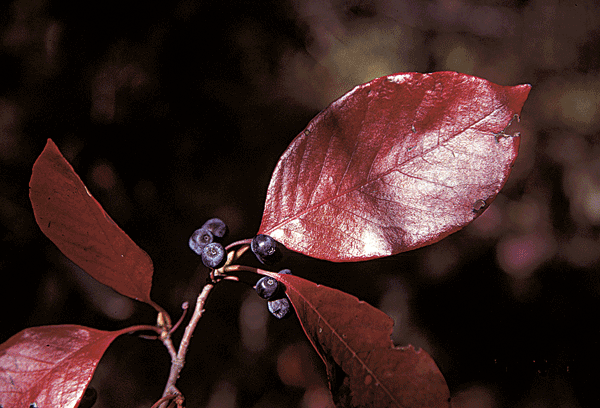

The bird species in your area and their food requirements change seasonally. In the spring, both migrant and resident birds feed on caterpillars and other invertebrates present on new plant growth (Figure 4). Large oaks (Quercus spp.), black cherry (Prunus serotina), and willows (Salix spp.) harbor many insects and spiders and are favored as foraging sites by orioles, tanagers, vireos, and warblers during spring migration. During the late spring and summer, breeding birds continue to feed on invertebrates but also eat fruits as they become available (see Table 1). Black willow (Salix nigra), a moisture-loving tree, harbors many insects during the summer. Insects and spiders are especially important to young songbirds born in the spring and summer because these foods fill the birds’ protein and calcium requirements for bone and tissue growth. As migrant birds and their offspring fly south in the fall, they seek out fruits, which are high in energy and help offset the energy lost during migration. In the fall, North Carolina’s year-round resident birds are joined by short-distance migrants, which breed in the northern United States and Canada and winter in the state. Winter residents, including cardinals, chickadees, juncos, robins, and sparrows, primarily eat fruits and seeds that persist on plants or on the ground (Figure 5). Yellow-rumped warblers, also known as myrtle warblers, eat the fruits of the wax myrtle (Myrica cerifera) in the winter.

Because the importance of different foods changes seasonally, it is best to provide a variety of food-producing plants in your yard.

- Include early- and late-fruiting species along with plants that produce winter seeds (see Table 1).

- Leave a portion of your yard or garden unmowed or unmanicured to allow fruit- and seed-producing plants to grow, especially during late summer, fall, and winter. Plants that produce fruit, such as blackberry and pokeweed, also harbor insects eaten by birds (Figure 6a and Figure 6b).

- A fallow garden left to grow on its own will provide abundant seed-producing plants, but it should be mowed or tilled at least once every three years. The timing of the disturbance will determine which plants grow (late summer disturbance may promote lower quality wildlife foods and will remove winter cover), so experiment with the frequency and season you disturb.

- Plants that are important for some birds because of the fruits and seeds they produce (such as oaks and black cherry) also offer a home to leaf-eating insects, which are in turn food for other birds. Plant diversity increases insect diversity (certain insects occur only on specific plant species), and lots of plant foliage creates more insect-holding leaf area.

Table 1. Important Fruit-Producing and Seed-Producing Native Plants in North Carolina and the Timing of Fruit or Seed Availability

| Fruit or Seed Type | Species | Common Name | Timing of Availability a | Birds Benefited b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soft mast fruits | Amelanchier arborea | Serviceberry | May–June | R,G,M,W,P |

| Morus rubra | Red mulberry | May–June | M,G,T,W,P,O | |

| Prunus angustifolia | Chickasaw plum | May–Aug. | M,G | |

| Vaccinium spp. (native) | Blueberry | May–Oct. | M,R,T,C,O | |

| Gaylussacia spp. (native) | Huckleberry | May–Oct. | M,R,T,C,O | |

| Rubus spp. (native) | Blackberry | June–July | R,M,G,T,W,O,C,P,S | |

| Sassafras albidum | Sassafras | June–July | M,R,T | |

| Chionanthus virginicus | Fringetree | June–Sept. | R,M,T | |

| Rhus spp. (native) | Sumac | June–Oct. | R,M,G,T | |

| Prunus serotina | Black cherry | July–Aug. | R,G,M,W,P,T,O | |

| Parthenocissus quinquefolia | Virginia creeper | July–Aug. | R,M,P,T | |

| Sambucus canadensis | Elderberry | July–Sept. | R,M,G,S,T,O,P | |

| Lindera benzoin | Spicebush | Aug.–Sept. | R,T | |

| Celtis occidentalis | Hackberry | Aug.–Oct. | R,M,G,W | |

| Nyssa sylvatica | Blackgum | Aug.–Oct. | R,M,P,T,W | |

| Phytolacca americana | Pokeweed | Aug.–Oct. | R,M,G,W | |

| Vitis spp. (native) | Grape | Aug.–Oct. | M,R,G,W,P,C,O,T,S | |

| Opuntia compressa | Cactus | Aug.–Oct. | M | |

| Berchemia scandens | Rattanvine | Aug.–Oct. | M | |

| Cornus florida | Flowering dogwood | Aug.–Oct. | R,M,G,W,P,T | |

| Cornus amomum | Silky dogwood | Aug.–Nov. | R,M,G,W,P,T | |

| Toxicodendron radicans | Poison ivy | Aug.–Nov. | R,P,M,C,S,W | |

| Callicarpa americana | American beautyberry | Aug.–Nov. | R,M | |

| Viburnum spp. (native) | Viburnum | Aug.–Dec. | M,W | |

| Myrica cerifera | Wax myrtle | Aug.–Dec. | M,G | |

| Ilex glabra | Gallberry | Aug.–Dec. | R,M,W,P | |

| Ilex verticillata | Winterberry | Aug.–Dec. | R,M,W,P | |

| Diospyros virginiana | Common persimmon | Sept.–Oct. | R,M,W | |

| Crataegus spp. (native) | Hawthorn | Sept.–Oct. | W,S,R | |

| Smilax spp. (native) | Greenbrier, or catbrier | Sept.–Nov. | M,R | |

| Sorbus arbutifolia | Chokeberry | Sept.–Nov. | W,R,G | |

| Aralia spinosa | Devil’s walkingstick | Sept.–Dec. | R,M | |

| Ilex decidua | Possumhaw | Sept.–Jan. | R,M,W,P | |

| Ilex vomitoria | Yaupon | Sept.–Jan. | R,M,W,P | |

| Ilex opaca | American holly | Sept.–Feb. | R,M,W,P | |

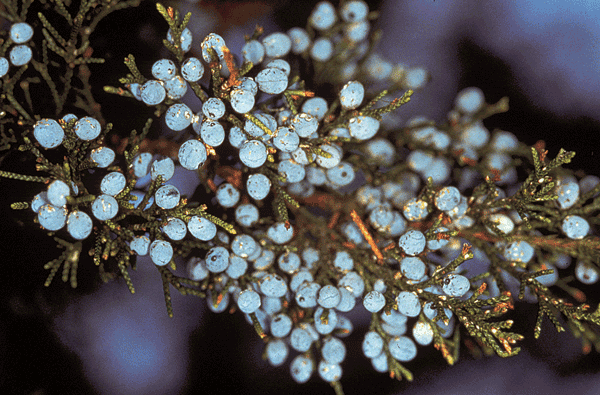

| Juniperus virginiana | Eastern redcedar | Sept.–Feb. | W,G,R,M | |

| Phoradendron serotinum | Mistletoe | Nov.–Jan. | W,R | |

| Hard mast fruits or seeds | Ulmus spp. (native) | Elm | March–April | G |

| Acer rubrum | Red maple | March–April | G,N,C,S | |

| Panicum spp. (native) | Panicgrass | April–Oct. | S,G | |

| Betula nigra | River birch | May–June | G,T,N,C,S | |

| Carex spp. (native) | Sedge | May–July | S,G | |

| Acer saccharum | Sugar maple | June–July | G,N,C | |

| Polygonum spp. (native) | Smartweed | June–Oct. | S,G | |

| Helianthus spp. (native) | Sunflower | July–Oct. | S,G,C | |

| Ostrya virginiana | Hophornbeam | July–Oct. | G,P | |

| Magnolia grandiflora | Southern magnolia | July–Oct. | P,T,G | |

| Ambrosia artimisifolia | Common ragweed | Aug.–Oct. | S,G | |

| Fraxinus spp. (native) | Ash | Aug.–Oct. | G | |

| Corylus americana | Hazlenut | Aug.–Oct. | P | |

| Rudbeckia fulgida | Orange coneflower | Aug.–Nov. | G,S | |

| Pinus spp. (native) | Pine | Aug.–Nov. | G,C,N,W | |

| Symphyotrichum spp. | Native Aster | Aug.–Feb. | G,S,C,N | |

| Carpinus caroliniana | Ironwood | Sept.–Oct. | G | |

| Echinacea purpurea | Purple coneflower | Sept.–Oct. | G,S | |

| Liriodendron tutipifera | Yellow-poplar | Sept.–Oct. | G | |

| Fagus grandifolia | American beech | Sept.–Oct. | P,N | |

| Castanea pumila | Chinquapin | Sept.–Nov. | P | |

| Quercus spp. (native) | Oaks | Sept.–Dec. | P,N,C,M | |

| Sorghastrum nutans | Indiangrass | Sept.–Feb. | G,S | |

| Coreopsis spp. (native) | Tickseed | Sept.–March | G,S | |

| Liquidambar styraciflua | Sweetgum | Oct.–Dec. | G | |

| Platanus occidentalis | Sycamore | Oct.–Jan. | G | |

| Solidago spp. (native) | Goldenrod | Oct.–March | G,S | |

| Andropogon spp. (native) | Bluestem | Oct.–March | G,S |

aModified from Radford, et al. (1968). Dates represent timing of fruit or seed presence on the plant; fruits and seeds of many plant species persist through the winter.

bAccording to Martin, Zim, and Nelson (1951). R = robins and thrushes; M = mockingbirds, catbirds, thrashers; S = sparrows, towhees; G = grosbeaks, buntings, cardinals, finches; T = tanagers, vireos; O = orioles; C = chickadees, titmice; W = waxwings; N = nuthatches; P = woodpeckers.

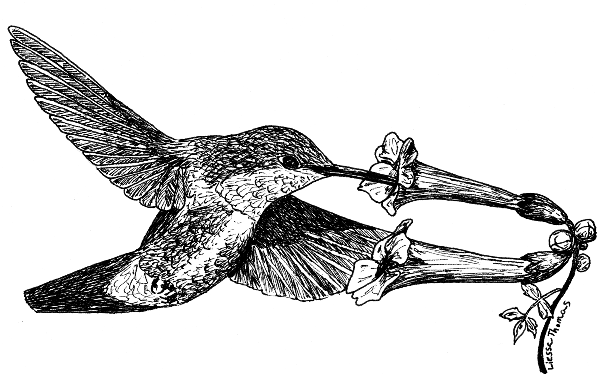

Hummingbirds

Hummingbirds help pollinate more than 160 native North American plants and are easily attracted to a backyard with a diversity of native plants. Ruby-throated hummingbirds, the only hummingbird species that breeds in North Carolina, feed on small insects and nectar (Figure 7a). They prefer the nectar from bright, tubular flowers, such as cross-vine (Bignonia capreolata), Carolina jessamine (Gelsemium sempervirens), and coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens). See Figure 7b, Figure 7c, and Figure 7d for examples of tube-shaped flowers. To attract hummingbirds, plant a variety of flowering plants that provide nectar throughout the warmer months (see Table 2). Hummingbird feeders are good artificial sources of nectar for these birds and should be filled with a boiled solution of four parts water to one part white sugar.

- Honey or red food coloring is not recommended, and feeders can be left up year-round.

- Ruby-throated hummingbirds will migrate even if feeders are left up, and some individual ruby-throats or other unusual hummingbird species may visit a feeder during the winter, especially in the warmer parts of the state. Most individual hummingbirds leave North Carolina by mid-October and don’t return until late March.

- If bees, wasps, or other insects are a problem at hummingbird feeders, try a five-to-one water-to-sugar mix, and avoid feeders with yellow in them (insects are attracted to the color yellow). Many feeders also come with bee and wasp guards that may help prevent problems with insects.

- Hang your feeder below an open container filled with water to deter ants; this acts as a moat that keeps ants out.

- Make sure you purchase a hummingbird feeder that can be cleaned thoroughly with a toothbrush and hot water each week to prevent the spread of bacteria or disease as hummingbirds visit the feeder.

Table 2. Favorite Hummingbird Wildflowers, Shrubs, and Vines

| Plant Species | Flowering Date |

|---|---|

| Carolina jessamine (Gelsemium sempervirens) | March–April |

| Buckeye (Aesculus spp.) | March–May |

| Wild columbine (Aquilegia canadensis) | March–May |

| Azalea (Rhododendron spp.) | April–May |

| Lyreleaf sage (Salvia lyrata) | April–May |

| Iris (Iris spp.) | April–May |

| Crossvine (Bignonia capreolata) | April–May |

| Coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens) | April–July |

| Fire pink (Silene virginica) | April–July |

| Indian pink (Spigelia marilandica) | May–June |

| New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus) | May–June |

| Beardtongue (Penstemon spp.) | May–June |

| Passionflower (Passiflora incarnata) | May–July |

| Phlox (Phlox spp.) | May–Aug. |

| Mallow (Hibiscus spp.) | June–Sept. |

| Bergamot, or bee balm (Monarda spp.) | June–Sept. |

| Trumpet vine (Campsis radicans) | June–Oct. |

| Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis) | June–frost |

| Blazing star (Liatris spicata) | July–Sept. |

| Cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis) | July–Oct. |

| Red morning glory (Ipomoea coccinea) | Aug.–frost |

Seed, Fruit, and Suet Feeders

Bird feeders supplement the natural foods in your backyard and concentrate bird activity for easy viewing. Black oil sunflower, safflower, white millet, and thistle seeds are all preferred types of birdseed. It’s best to buy each seed type separately and in bulk. Seed mixes often contain empty seed hulls and undesirable seed types. Buying in bulk also cuts down on cost.

- Sunflower seeds are the best all-around seed type for your feeders. The larger, white-striped sunflower seeds are not as desirable as black oil sunflower seeds because the white stripes have less of their weight in the kernel. Sunflower seeds generally should be presented in above-ground platform feeders or covered feeders. Cardinals, chickadees, grosbeaks, finches, nuthatches, and titmice eat sunflower seeds.

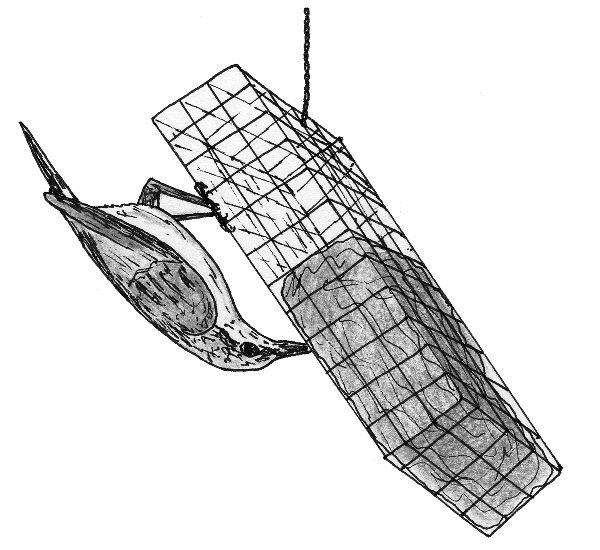

- Thistle seeds can be used in the popular tube feeders or in mesh bags (Figure 8). Thistle attracts pine siskins and American goldfinches.

- White millet should be spread on the ground beneath shrubs, in piles of brush or plant clippings, or under above-ground feeders. Juncos, mourning doves, eastern towhees, and sparrows eat millet.

- Suet, whether store-bought or homemade, is enjoyed by an incredible variety of birds, including bluebirds, catbirds, nuthatches, orioles, pine warblers, woodpeckers, wrens, and yellow-rumped warblers (Figure 9). To make suet at home, mix raisins, chopped apples, leftover birdseed, oatmeal, peanut hearts, cracked corned, or peanut butter with melted animal fat, vegetable shortening, or lard. Straight peanut butter is not recommended because birds may have trouble swallowing it.

- Sliced oranges or apples, placed flesh side up on tree limbs or wooden boards, may attract orioles or tanagers to your yard.

Feeders are used most frequently during the winter when natural foods are in shortest supply. Once feeding has begun in the winter, it should be continued through the season. Otherwise, feeding birds may be left without a dependable food source. Squirrels can be excluded from feeders by using squirrel-proof devices (weight-sensitive motorized or treadle feeders) or by mounting the feeder 4 to 6 feet up a post above a baffle. All feeders should ALWAYS be placed within 10 feet of a brush pile or shrubby vegetation, especially evergreen plants. This allows smaller birds to quickly escape into nearby cover from predators like Cooper’s hawks. However, feeders placed within shrubbery are easily accessible to stalking cats, and feeders placed close to windows can lead to bird-window collisions. Feeders should be cleaned every two to three weeks to prevent disease transmission among birds.

Water and Birdbaths

Although water isn’t a limiting component of bird habitat in most of North Carolina, it may be scarce in some areas or during periods of drought. Birds normally obtain the water they need from their food, temporary pools, dew on plants or the ground, or permanent sources. If natural sources of water are not available in your yard or on a nearby property, a birdbath or artificial pond can provide an adequate water source and a focal area for bird-watching.

- Birdbaths should be shallow (2 to 3 inches deep) and made of a rough surface to ensure good footing. The basin should be 24 to 36 inches in diameter with a lip or edge for perching.

- Homemade birdbaths can be made of garbage can lids, rocks, or hollowed-out stumps because some birds don’t like to perch high off the ground to drink or bathe.

- Birdbaths are best if positioned on or near the ground and about 15 feet from a perch or shrubby cover, but unused baths can be moved nearer to cover.

- Moving water is a real draw for birds, and inexpensive pumps can be put into backyard ponds to provide the sound of running water that attracts birds and other wildlife.

- It is important to clean your birdbath weekly and keep it full of fresh, cool water. A birdbath can be cleaned with soap or chlorine bleach as long as it is rinsed thoroughly with water.

Dense vegetation provides birds with places to escape from harsh weather and predators, such as hawks or house cats. Different bird species require different types of substrates (grasses, shrubs, tree limbs, moss) to support their nests; therefore, a variety of plant species of different growth forms may aid in increasing the diversity of birds nesting in your yard. Avoid pruning trees and shrubs during the nesting season—from early March through late July. Bird nests can be damaged or exposed to predators and the weather if vegetation surrounding the nest is removed. Just as with food, cover requirements change seasonally. During the spring and summer, foliage is abundant and cover is plentiful in a yard with a combination of shrubs, vines, wildflowers, grasses, and trees. However, cover can become scarce during the winter. It is important to provide evergreen trees and shrubs, including native pines (Pinus spp.), American holly (Ilex opaca), yaupon (Ilex vomitoria), wax myrtle, and eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana) in your backyard, especially adjacent to important feeding and watering spots (Figure 10a and Figure 10b). Evergreens or dense shrubbery can provide nighttime roosting spots for birds throughout the year, especially during harsh winter weather.

Nest Boxes

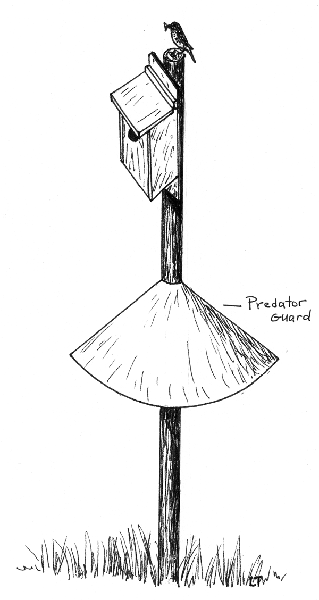

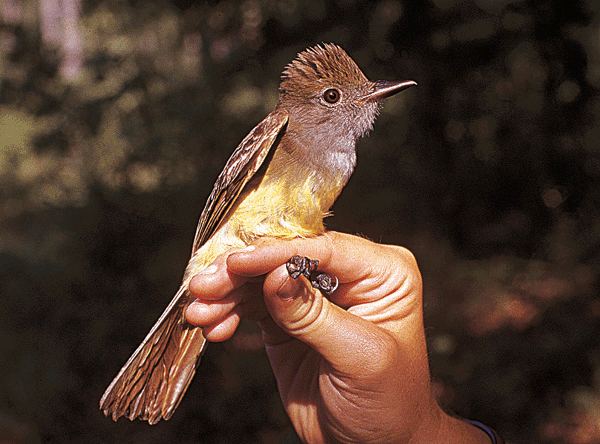

Cavity-nesting birds build their nests in old woodpecker cavities. Dead trees are important nesting sites for these birds and should be protected when possible. Because dead trees often are considered unsightly or liability risks, nest boxes frequently are used as surrogates for natural cavities (Figure 11). They provide nesting sites for a variety of bird species, including bluebirds, chickadees, great crested flycatchers, screech owls, titmice, and nuthatches (Figure 12a and Figure 12b).

- Nest boxes should be built following recommended dimensions for box height, box width, entrance hole diameter, and placement height (see Table 3).

- A well-designed nest box is made of sturdy lumber (pine, redcedar, or cypress), has a metal entrance guard to prevent expansion by woodpeckers or squirrels, and does not have a perch (Figure 11). Perches increase the use of nest boxes by aggressive birds like house sparrows and European starlings and may limit use by native birds.

- All boxes need ventilation and drainage.

- To prevent easy access by nest predators, such as snakes and squirrels, place nest boxes on a wooden or metal post away from overhanging tree limbs. A predator guard, or baffle, can be placed below nest boxes to further limit nest predation.

- Place boxes in a location appropriate for the target bird species. If a box goes unused for a year, it can be moved to another spot before the new nesting season begins in early March.

- Fill nest boxes meant for woodpeckers with wood shavings or sawdust, so the adults can complete the excavation process (digging down through the sawdust) that is important for pair bonding.

- Nest boxes can be cleaned out in February before the new nesting season begins. Build nest boxes that can be emptied.

Table 3. Recommended Dimensions for Nest Boxes

|

Bird Species |

Floor Size (Interior) |

Entrance Hole |

Box Height |

Distance Above Ground* |

|

|

Height |

Diameter |

||||

|

American kestrel |

8×8 |

10–12 |

3 |

14–16 |

10–20 |

|

Barn owl |

10×18 |

4 |

6 |

15–18 |

12–18 |

|

Barred owl |

13×13 |

14–18 |

6–8 |

22–28 |

10–30 |

|

Brown-headed nuthatch |

4×5 |

6–8 |

1.25 |

8–10 |

5–15 |

|

Carolina chickadee |

4×4 |

6–8 |

1 1/8 |

8–10 |

4–15 |

|

Carolina wren |

4×4 |

4–6 |

1.5 |

6–8 |

5–10 |

|

Downy woodpecker |

4×4 |

6–8 |

1.25 |

8–10 |

5–15 |

|

Eastern bluebird |

5×5 |

6–10 |

1.5 |

8–12 |

4–6 |

|

Eastern screech owl |

8×8 |

9–12 |

3 |

12–15 |

10–30 |

|

Great crested flycatcher |

6×6 |

6–10 |

1.5 |

8–12 |

5–15 |

|

Hairy woodpecker |

6×6 |

9–12 |

1.5 |

12–15 |

8–20 |

|

Pileated woodpecker |

8×8 |

12–20 |

3×4 (oval) |

16–24 |

15–25 |

|

Red-bellied woodpecker |

6×6 |

9–12 |

2.5 |

12–15 |

10–20 |

|

Red-headed woodpecker |

6×6 |

9–12 |

2 |

12–15 |

10–20 |

|

Tufted titmouse |

4×4 |

6–10 |

1.25 |

10–12 |

5–15 |

|

White-breasted nuthatch |

4×4 |

6–8 |

1.5 |

8–10 |

5–15 |

|

Wood duck |

10×10 |

12–16 |

3×4 (oval) |

20–24 |

6–20 |

* Boxes mounted on poles should be placed at the lower end of the recommended mounting heights.

Initial Inventory and Plan

Before you begin any habitat improvements, map the existing vegetation in your yard. From this base map, identify areas where food and cover are limited and where they are abundant. Then, plan your new backyard landscape. For example, planting a variety of fruiting plants like spicebush and blackgum will supplement the bird foods present in nearby natural areas (Figure 13a and Figure 13b). Make sure to incorporate all habitat requirements of target bird species and to map the changes. You can use a separate clear overlay for each vertical layer (canopy, shrub, herbaceous/ground cover) of your landscape. When refining your plan, consider the surrounding areas or what types of properties are adjacent to your own. For example, evergreen vegetation may be lacking if you live in an area dominated by deciduous plants. Also, plan for viewing areas by placing important food sources (bird feeders or fruiting shrubs) in sight of windows and paths. Consider the moisture and light requirements of plants when including them in your plan. Map moisture-loving plants in low-lying areas, and position shade-loving plants under large trees. Concentrate similar types of vegetation in beds or clumps to allow birds easy access to seasonally abundant food sources without excessive movement and increased exposure to predators. Clumping similar species and placing shorter herbs and shrubs in front of taller vegetation also makes the landscape more attractive to people. Remember to include escape cover throughout the yard and provide safe travel corridors (hedgerows) into interior portions of the yard. Most birds are territorial during the breeding season, so situate nest boxes and feeders at least 100 feet apart to prevent territory overlap. Birds prefer an untidy garden or landscape. Mowing, pruning, edging, and weeding may lower the quality of your yard as bird habitat. However, local ordinances or the opinion of neighbors may prevent you from allowing your yard to become a true jungle. Before making any drastic changes that might upset your neighbors, let others know what you plan and explain why you intend to make the changes. Consider locating unsightly brambles, unmowed grasses, piles of limbs and debris, or unpopular plants like pokeweed in a hidden portion of your yard.

Implementation and Evaluation

Work within your own schedule and budget when implementing your backyard bird habitat plan. Consider each step as a building block, and set monthly time and expense budgets. Although it is not necessary to complete your backyard habitat project within a set timeframe, it is important to provide some food, water, and cover as soon as possible. It will take time, maybe several years, for some of your improvements to begin attracting birds. Most small to medium-sized backyards (0.1 to 1 acre) are three- to five-year projects. Take pictures of your yard and document the birds you see from the initial planning steps to the final finished habitat. Keep a record of the bird species observed and their locations within your yard. Use the record to evaluate your improvements. If certain species are absent or certain parts of the yard remain unused, make modifications to improve conditions. Remember, promote variety and vertical structure, be creative, be patient, and have fun.

Neighborhood and Greenspace Planning

The methods used to plan and construct suburban and urban land developments have a significant influence on the future quality of these areas as bird habitat. Here are some recommendations for maintaining or improving neighborhoods and commercial developments as bird habitat:

- Avoid wide, grassy, or landscaped medians in the center of two-laned neighborhood roads (Figure 14). Avoid planting shrubs or other vegetation attractive to birds in medians or along roadsides; birds attracted to these plantings may be killed by collisions with passing cars.

- Protect streamside forests and other riparian vegetation during development activities. Forest buffers more than 100 feet wide adjacent to wetland areas provide habitat for rare and more sensitive bird species.

- Leave naturally occurring vegetation (herbs, shrubs, and trees) in place as much as possible when developing subdivisions.

- Cluster or concentrate homes within a subdivision and leave larger areas of undeveloped forest as greenspace. The greenspace can be used for hiking and nature watching and provides an excellent bird habitat.

- Avoid planting extensive areas in non-native grasses, such as tall fescue and bermudagrass, because they provide poor quality bird habitat and require excessive watering, fertilizing, and pesticide application. As an alternative to managed turf, retain areas of leaf litter, which are attractive foraging areas for brown thrasher, eastern towhee, and other ground-feeding bird species.

- Replant home lots with native vegetation, making sure to include a variety of plant species.

- Plant large-maturing trees, especially oaks, in areas with adequate space above and below ground. Avoid planting these trees where they will overgrow their space and interfere with overhead utility lines or crowd homes and other structures.

- Connect remnant patches of greenspace, including city parks and school grounds, with forested corridors (also known as greenways); these corridors provide excellent hiking, biking, and bird-watching trails.

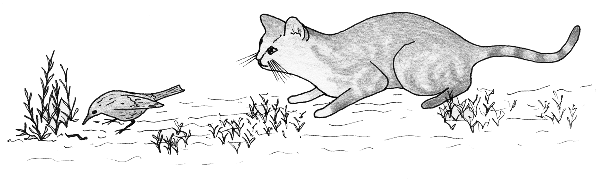

Domestic and Feral Cats

Outdoor and feral (able to live in the wild) domestic cats (i.e., house cats) kill billions of songbirds and other wildlife each year in the United States. Have you ever said, “Not my cat”? Almost all domestic cats will kill birds, whether the cats are well-fed or not. It’s a natural instinct for cats to kill prey species, including the birds in your backyard (Figure 15).

Researchers also have found that even cats with bells on their collars can kill birds and other small animals. Spay and neuter your pets, support legislation to prevent free-ranging pets, follow local leash laws when walking a pet outdoors, and keep your cat INDOORS. Birds face many dangers each day, so your efforts are important to help ensure the long-term conservation of North Carolina’s birds.

Additional Sources of Information

Books

Barnes, Thomas. 1999. Gardening for the Birds. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky.

Ehrlich, Paul, David Dobkin, and Darryl Wheye. 1988. The Birder’s Handbook. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Harrison, Hal. 1975. A Field Guide to the Birds’ Nests. New York: Houghton Mifflin Co.

Martin, Alexander, Herbert Zim, and Arnold Nelson. 1951. American Wildlife and Plants: A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits. New York: Dover Publications.

Miller, James, and Karl Miller. 1999. Forest Plants of the Southeast and Their Wildlife Uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

National Geographic Society. 1999. Field Guide to the Birds of North America. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society.

Peterson, Roger Tory. 1980. A Field Guide to the Birds of Eastern and Central North America. New York: Houghton Mifflin Co.

Radford, Albert Ernest, Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. 1968. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Sibley, David Allen. 2016. The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Eastern North America. 2nd edition. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Stokes, Donald, and Lillian Stokes. 1996. Stokes Field Guide to Birds. New York: Little, Brown & Co.

Wasowski, Sally, and Andy Wasowski. 1994. Gardening with Native Plants of the South. Dallas, Texas: Taylor Publishing Co.

NC State Extension Publications

For more information, request the following Working with Wildlife (WWW) and Urban Wildlife (AG) publications from your local Cooperative Extension Center or find them on the Extension Publications Catalog.

- Songbirds and Woodpeckers, WWW-4

- Snags and Downed Logs, WWW-14

- Building Songbird Boxes, WWW-16

- Hummingbirds and Butterflies, WWW-20

- Butterflies in Your Backyard, AG-636-02

- Landscaping for Wildlife with Native Plants, AG-636-03

Online Resources

- NC State Extension Wildlife Friendly Landscapes

- NC State Extension Wildlife

- North Carolina Partners in Flight

- National Wildlife Federation

- The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University

- North American Bluebird Society

- American Bird Conservancy

- National Audubon Society

- North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences

- North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission Wildlife Rehabilitation

Acknowledgments

Funding for creation of this publication was provided in part through an Urban and Community Forestry Grant from the North Carolina Forest Service, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, in cooperation with the USDA Forest Service, Southern Region.

Illustrations by Liessa Thomas Bowen.

Publication date: May 6, 2022

AG-636-01

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.