Pickleworms (common on most cucurbits) and squash vine borers (found on squash) can cause serious damage to field-grown cucurbits. In the greenhouse, cucumbers are likely to be infested with aphids, spider mites, and leafminers. Cucumber beetles are common on cucumbers outdoors and in greenhouses. Cucumber beetles are vectors of the bacterial wilt organism and help spread cucumber mosaic virus.

A. Pests that feed externally on the plant

- Chewing insects that leave holes or scars in foliage, fruit, blossoms, and buds

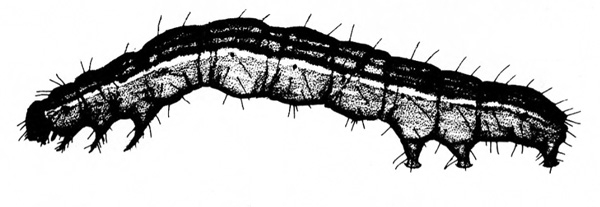

- Cabbage looper—The body of this green caterpillar is up to 13/16 inch long, tapering toward the head, with white, longitudinal stripes. It has three pairs of legs near the head and three pairs of fleshy prolegs (Figure 1). Young larvae are found on the undersides of leaves. Mature larvae seek protection of large leaves near the center of plants. They consume tender leaf tissue, leaving the tougher veins. (For more information about cabbage loopers, see “Pests of Crucifers.”)

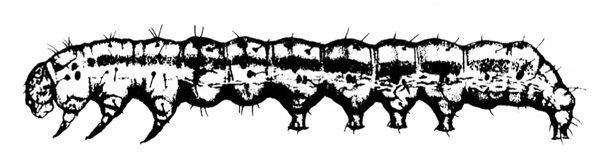

- Corn earworm (also known as tomato fruitworm)—This moderately hairy caterpillar is up to 1 3/4 inches long with three pairs of legs and five pairs of prolegs (Figure 2). Early instars are cream colored or yellowish green with few markings. Later instars are green, reddish, or brown with pale, longitudinal stripes and scattered black spots (Figure 3). It is a late-season pest that devours flowers and scars or even bores into fruits. (For more information about corn earworms, see “Pests of Sweet Corn.”)

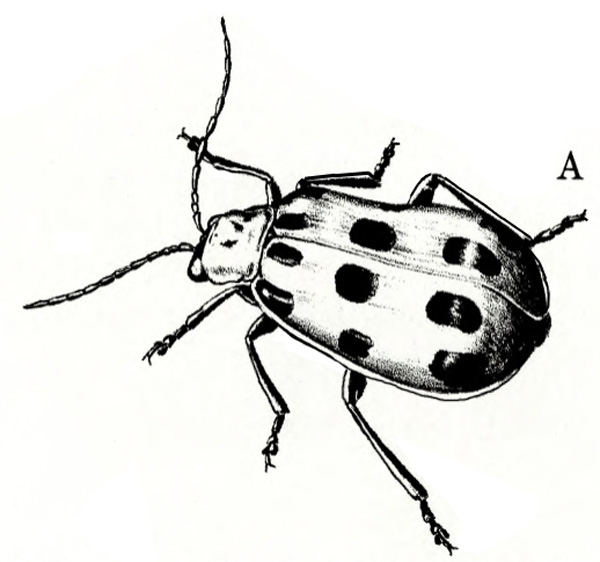

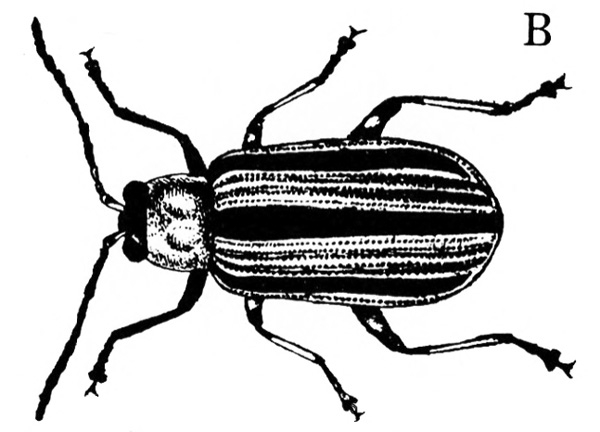

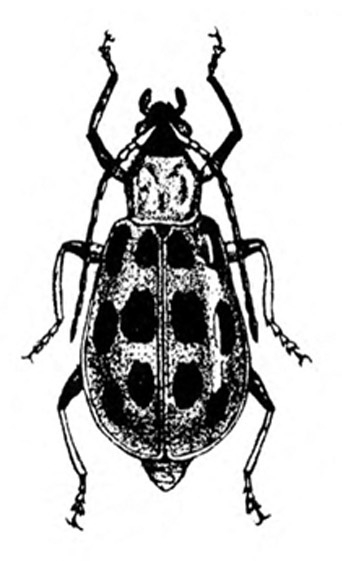

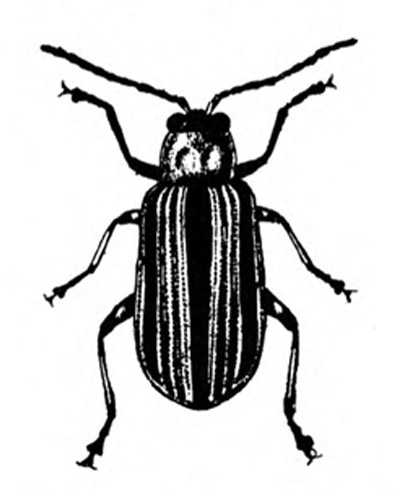

- Cucumber beetles—These oval-oblong beetles are between 3/16 inch long (striped cucumber beetle) and 1/4 inch long (spotted cucumber beetle). The spotted cucumber beetle has a bright-yellowish-green body with 12 black spots on the wing covers (Figure 4A). The striped cucumber beetle has a pale-yellow body with three black stripes on the wing covers (Figure 4B). They chew holes in foliage, girdle stems, damage blossoms, and scar fruit.

- Melonworm—A greenish caterpillar up to 13/16 inch long, it has three pairs of legs near the head and five pairs of prolegs (Figure 5). Most larval stages have two white, slender, well-separated stripes down the back. The melonworm feeds primarily on tender foliage.

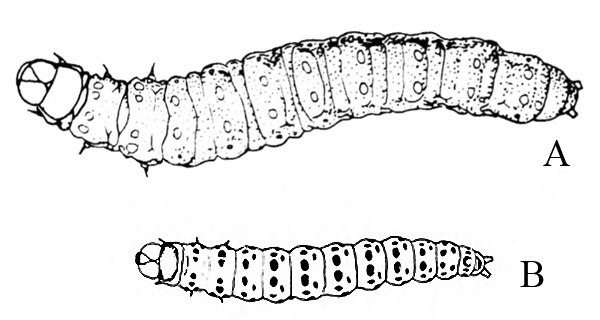

- Pickleworm—Young larvae are smaller than 3/8 inch long, colorless or pale yellow with dark spots, with three pairs of legs near the head and five pairs of prolegs (Figure 6). They feed within blossoms or on small leaves at the growing tips of vines. Eventually they enter the fruit.

- Pests that cause discoloration or distortion of the upper plant

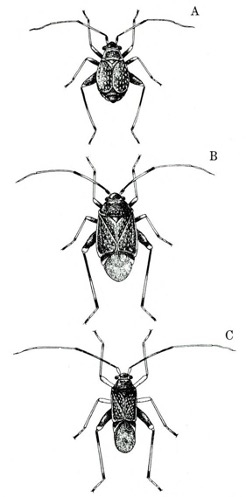

- Garden fleahopper—These small, black bugs are about 1/32 inch to a little more than 1/16 inch long (Figure 7A–C). Nymphs are smaller and yellow to dark green with a black spot on each side. All stages of the garden fleahopper jump readily. These pests suck sap from foliage. Severe infestation can cause major defoliation, reducing crop yield.

- Greenhouse whitefly—These white, mothlike insects are about 1/16 inch long and are found in conjunction with tiny, yellow, newly hatched, mobile nymphs (crawlers) or green, oval, flattened, immobile nymphs and pupae (Figure 8). They cause yellowing of leaves and stunted, nonreproductive plants. Honeydew and black sooty mold may be present on leaves. (For more information about greenhouse whiteflies, see “Pests of Tomato.”)

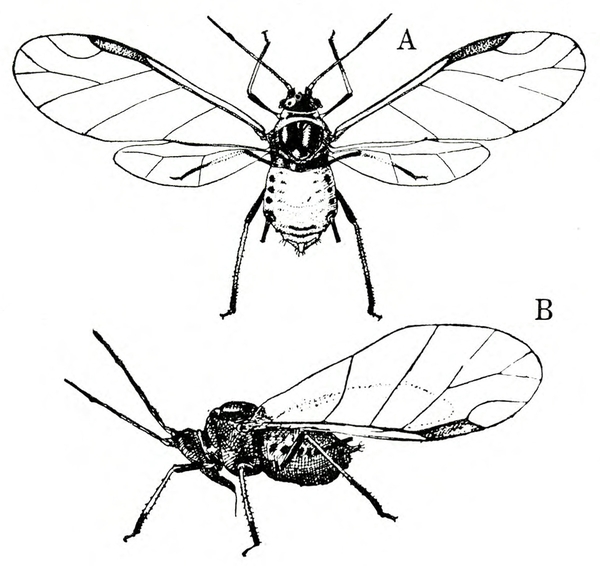

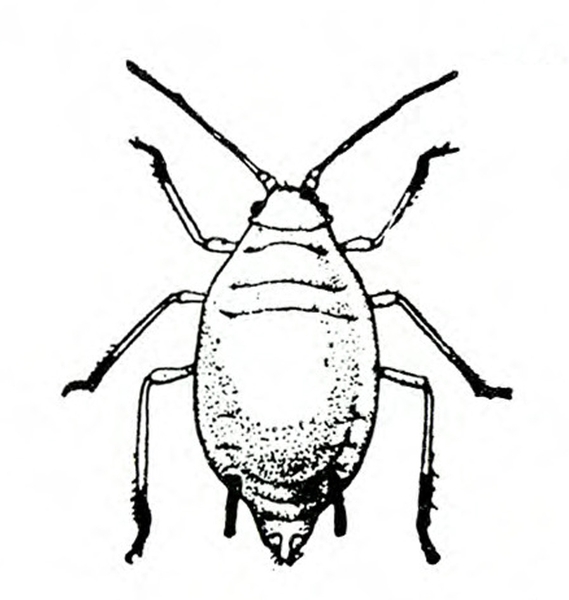

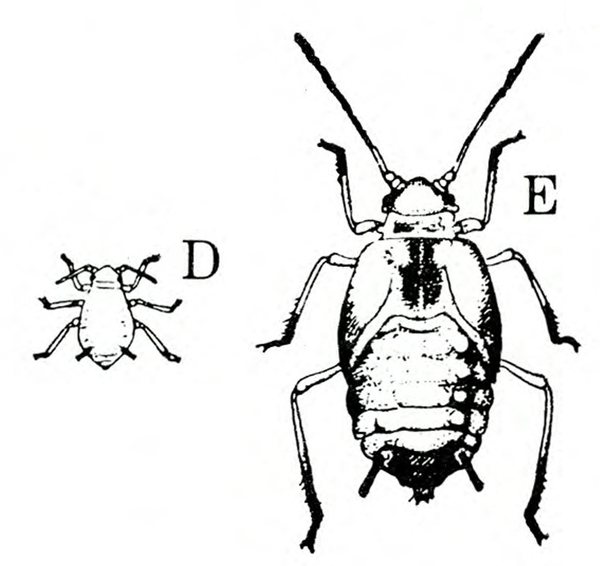

- Melon aphid—A soft-bodied, pear-shaped insect a little more than 1/16 inch long, it has a pair of dark cornicles and a cauda protruding from the abdomen. Their bodies are yellow in hot, dry summers and pale to dark green in cool seasons. They are winged or wingless (Figure 9A–B), with the wingless form most common. They feed in colonies, causing leaves to curl downward and pucker, wilt, and eventually turn brown. They secrete honeydew, making plants sticky and promoting the growth of sooty mold.

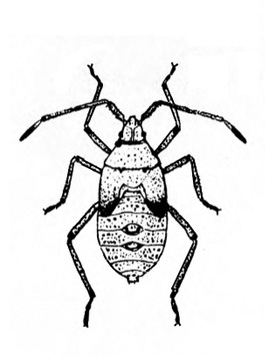

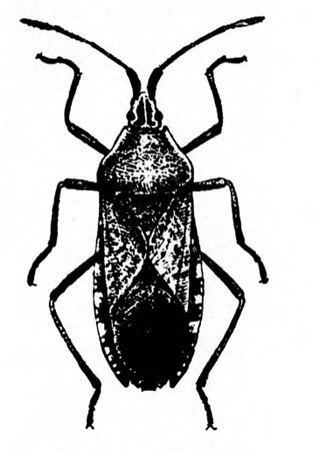

- Squash bug nymph and adult—The light-gray to dark-brown bugs are up to 5/8 inch long. The nymphs (Figure 10A) range in size from 1/8 to 3/8 inch. The adult is flat across the back, mottled yellow underneath, and oval-elongate in shape (Figure 10B). These pests congregate on vines. Infested vines blacken and wither. They sometimes attack fruit.

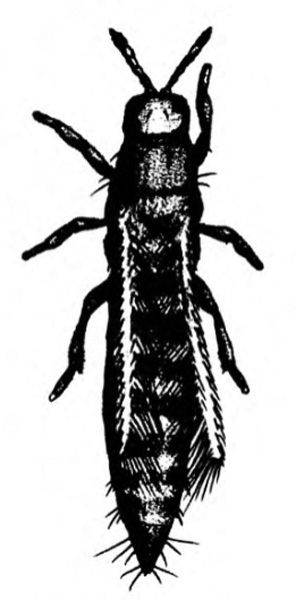

- Thrips—Slender, pale yellow to dark brown, and 1/16 inch or less in length, adult thrips have two pairs of narrow, fringed wings (Figure 11). Immature thrips are pale with red eyes. They rasp foliage, creating pale flecks, blotches, or scratch-like markings on leaves and blossoms. Infested leaves may be distorted and disfigured, with specks of black excrement. (For more information about thrips, see “Pests of Beans and Peas.”)

- Twospotted spider mite—These tiny, almost microscopic, pale-to-dark-green pests have two or four dark-colored spots. Adults and nymphs have eight legs, and larvae have six. Adult females are almost 1/64 inch long and oval; males taper toward the rear (Figure 12). They feed on the undersides of leaves. Infested foliage has silvery or pale-yellow stipples. Leaves eventually fade and dry up. Silken webs are common on undersides of leaves. (For more information about twospotted spider mites, see “Pests of Beans and Peas.”)

B. Pests that feed inside leaves, seeds, stems, roots, or fruit

-

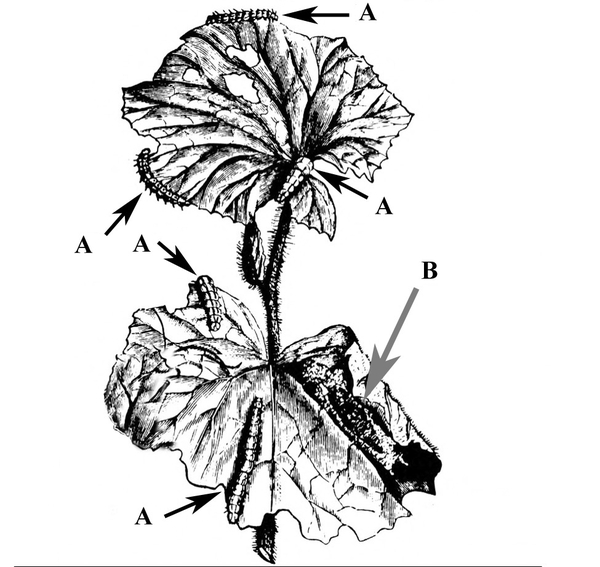

- Pickleworm—This yellow-green caterpillar is up to 13/16 inch long with a dark head, three pairs of legs near the head, and five pairs of prolegs; smaller larvae are pale yellow with dark spots (Figure 13A–B). Pickleworms bore into the side of fruits before the rind hardens and tunnel inside, leaving masses of soft excrement. The fruit rots or sours. Vines may be riddled with holes.

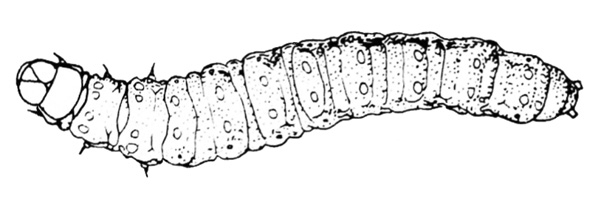

- Seedcorn maggot—This white to yellow maggot is up to 1/4 inch long and legless, with the body tapered toward the head (Figure 14). It feeds underground on roots, seeds, and sometimes stems. Infested seedlings appear unthrifty and may yellow, wilt, and die. (For more information about seedcorn maggots, see “Pests of Beans and Peas.”)

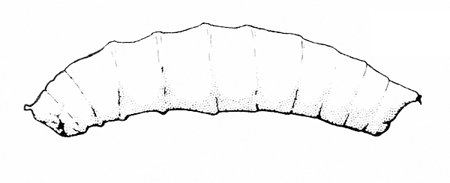

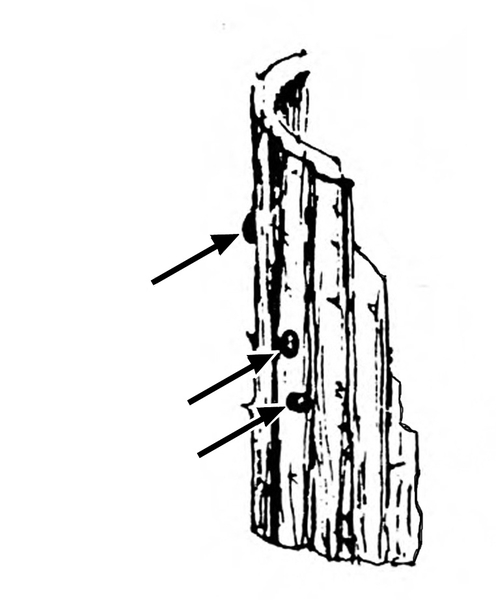

- Squash vine borer—Thick-bodied, whitish, and wrinkled, this caterpillar is up to 1 inch long with a brown head, three pairs of legs near the head, and five pairs of prolegs (Figure 15 and Figure 16). It has two transverse rows of spines on each proleg. Borers cause sudden wilting of a long runner or entire plant. Greenish-yellow excrement protrudes from a hole in the stem. The pest entrance hole is usually near the ground. Vines become girdled, rot, and die. Fruit may be infested.

Vegetable leafminer—A colorless to bright-yellow maggot up to 1/8 inch long, it has a pointed head (Figure 17). It makes a serpentine mine that is slightly enlarged at one end. (For more information about vegetable leaf miners, see “Pests of Tomato.”)

Cucumber Beetles

Spotted cucumber beetle, Diabrotica undecimpunctata howardi Barber, Chrysomelidae, COLEOPTERA

Striped cucumber beetle, Acalymma vittatum (Fabricius), Chrysomelidae, COLEOPTERA

Description

Adult—Spotted cucumber beetles are 1/4 inch long, oblong-oval in shape, with beaded antennae (Figure 18A). They are bright-yellowish-green with a black head, legs, and antennae. Wings are marked with 12 black spots. Slightly smaller at 3/16 inch long, the striped cucumber beetle is pale yellow with a black head and three black stripes down its back (Figure 18F).

Egg—The oval, orange-yellow eggs of both species are found in clusters of 25 to 50 on undersides of host leaves. The eggs of both the spotted cucumber beetle (Figure 18B) and striped cucumber beetle (Figure 18G) are almost 1/32 inch long, although the egg of the striped cucumber beetle is more slender.

Larva—Cucumber beetle larvae have a yellow-white, somewhat wrinkled body with three pairs of brownish legs near the head and a single pair of prolegs near the tip of the abdomen. When fully grown, spotted cucumber beetle larvae are 1/2 to 3/4 inch long (Figure 18C); striped cucumber beetle larvae are only 3/8 inch long and have a more flattened abdomen (Figure 18H).

Pupa—Pupae of both the spotted cucumber beetle (Figure 18D) and striped cucumber beetle (Figure 18I) are white, tinged with yellow, and 1/4 to 5/16 inch long. A pair of black spines is located at the tip of the abdomen.

Biology

Distribution—These native insects occur from Mexico to Canada. They are most abundant and destructive in their southern range, but usually are not troublesome in areas with sandy soils.

Host Plants—Adult striped cucumber beetles prefer cucumber, cantaloupe, winter squash, pumpkin, gourd, summer squash, and watermelon. They also feed on bean, pea, corn, and the blossoms of several wild and cultivated plants. Larvae develop on all related cucurbits. The adult spotted cucumber beetle has a wider host range and, in addition to cucurbits, may be found on bean, pea, potato, beet, tomato, eggplant, and cabbage. The larva, known as the southern corn rootworm, feeds on the roots of corn, peanut, small grains, and many wild grasses.

Damage—Striped and spotted cucumber beetle adults feed on the foliage and stems of cucurbits all season. They often girdle stems by gnawing on the tender shoots of seedlings. As plants develop, beetles also feed on blossoms and leave scars on the fruit. Adult cucumber beetles harbor a bacterial wilt organism (Pseudomonas lachrymans) during the winter and transmit it during the growing season. They also help spread squash mosaic virus. Larvae of both species injure plants by feeding on roots (Figure 18E) and tunneling through stems.

Life History—Unmated adults overwinter in neighboring woodlands under leaves and trash or around the bases of plants that have not been killed by frost. Adults leave their winter sites in late March. Before cucurbits are available, the beetles subsist on the pollen and petals of many plants. As soon as cucumber, squash, or melon vines appear, beetles devour cotyledons and stems. Females of the overwintering generation lay eggs from late April through early June, with each female striped cucumber beetle depositing as many as 125 eggs and each female spotted cucumber beetle depositing 500 eggs or more. Depending on temperature, eggs incubate for five to ten days before hatching. Larvae feed in the soil on stems and roots for two to four weeks before pupating. First-generation adults emerge from late June to early July. Over the next six to nine weeks, the life cycle is repeated, with second-generation adults being prevalent from September to November. These later adults congregate and feed on clover and alfalfa until winter. They may come out to feed during warm periods in January and February. Two generations and sometimes a partial third generation are produced each year.

Control

Several cultural measures discourage cucumber beetles. Early plowing or disking removes vegetation and discourages egg-laying. Delayed planting, when germinating conditions are more favorable, and heavy seeding rates ensure a good stand. Wire or cloth screen protectors shaped like cones will keep beetles off home garden plants until they get established.

The use of resistant varieties is perhaps the most important control tactic. The following cucurbit varieties are resistant to spotted cucumber beetles as seedlings and also have resistant foliage later in the season: Blue Hubbard (squash) and Ashley, Chipper, and Gemini (cucumber). Use of resistant varieties may not provide complete pest control where infestations are heavy.

A foliar insecticide applied at the cotyledon stage will retard cucumber beetle feeding and encourage plant establishment. Where pests are abundant, additional foliar applications may be needed to prevent beetles from spreading bacterial wilt and squash virus. For recommended insecticides and rates, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Garden Fleahopper

Microtechnites bractatus (Say), Miridae, HEMIPTERA

Description

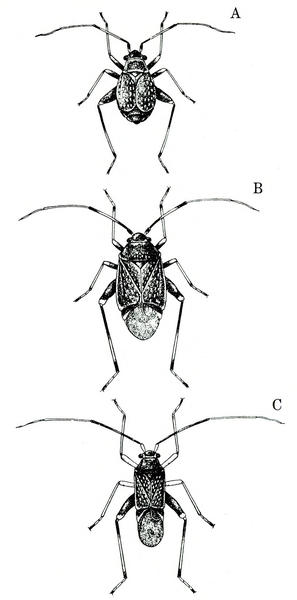

Adult—There are three forms of adult garden fleahopper: oval-bodied, short-winged females, slender, long-winged females, and slender, long-winged males (Figure 19A–C). All forms are black and have long legs and antennae. They tend to jump actively but are also capable of flying. The body may be a little more than 1/16 inch long.

Egg—Each white, somewhat curved egg is rounded at one end, truncate at the other, and almost 1/32 inch long. Usually inserted into the plant, the egg is seldom seen.

Nymph—Nymphs are pale yellow to dark green, range from almost 1/32 to 1/16 inch long, and have five instars. Later instars have a distinct black spot on each side of the first thoracic segment. All stages jump readily.

Biology

Distribution—Though infestations are sporadic, garden fleahoppers can be found throughout the eastern United States and in some western areas.

Host Plants—The garden fleahopper infests a wide range of garden, ornamental, and forage plants in addition to many weeds and grasses. Vegetable hosts include bean, beet, cabbage, celery, corn, cowpea, cucumber, eggplant, lettuce, pea, pepper, potato, pumpkin, squash, sweetpotato, and tomato.

Damage—Garden fleahoppers cause pale spots to develop on leaves by sucking sap from the foliage. Heavily infested foliage dies and drops from the plant. Defoliation interferes with growth and development of crops, reducing yield.

Life History—Garden fleahoppers overwinter as eggs, which are laid from August through September. Nymphs emerge in early spring and feed on the undersides of leaves. Nymphs feed 11 to 35 days before maturing into adults, with the duration of development depending on temperature. Adults live one to three months. Each female lays about 105 eggs, inserting them into punctures made by her mouthparts in stems or leaves. About 12 to 20 days later, eggs hatch, and the life cycle is repeated. Five generations are completed each year.

Control

For up-to-date chemical recommendations, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Melon Aphid

Aphis gossypii Glover, Aphididae, HEMIPTERA

Description

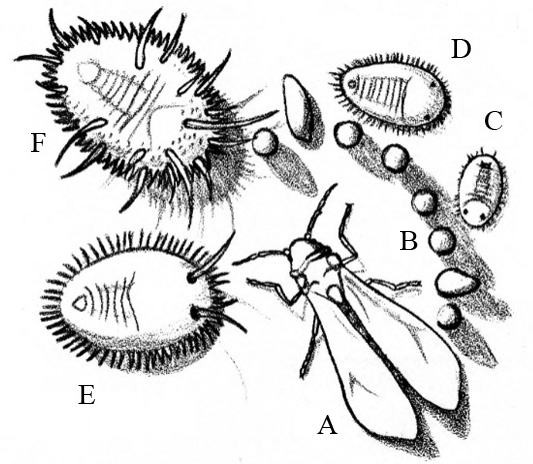

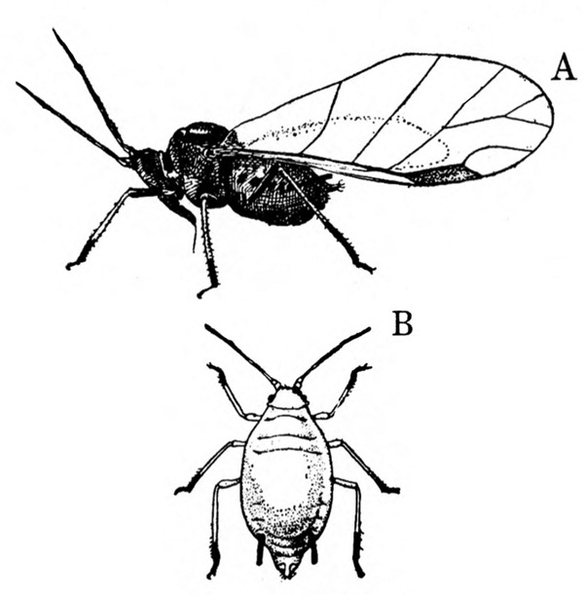

Adult—This soft-bodied, pear-shaped insect is pale to dark green in cool seasons and yellow in hot, dry summers. Though winged forms develop periodically (Figure 20A–B), most adults are wingless (Figure 20C) and a little more than 1/16 inch long. All forms have a pair of tailpipe-like appendages known as cornicles.

Egg—The egg stage does not occur in North Carolina.

Nymph—The nymph is smaller than the wingless adult but similar in shape and color (Figure 20D–E).

Biology

Distribution—The melon aphid is distributed throughout the temperate, subtropical, and tropical zones of the world. It occurs in all areas of North Carolina.

Host Plants—This pest may infest a wide range of vegetable and ornamental crops. Vegetable hosts include asparagus, bean, beet, cowpea, cucurbits, eggplant, okra, spinach, and tomato. Among cucurbits, cucumber and melon are most likely to be infested, followed by squash and pumpkin.

Damage—Damage usually becomes obvious on cucurbits after the vines begin to run. If weather is cool during spring, populations of natural enemies will be slow in building, and heavy aphid infestations may result. Congregating on lower leaf surfaces and terminal buds, aphids pierce plants with their needlelike mouthparts and extract sap. When this occurs, leaves curl downward and pucker (Figure 20F). Wilting and discoloration follow. Aphid damage weakens plants and may reduce fruit quality and quantity. Honeydew secreted by aphids makes plants sticky and promotes development of black sooty mold on plant foliage.

Life History—In North Carolina, melon aphids spend part of the winter on weed hosts and in gardens on cold-tolerant plants such as spinach. They feed during warm periods until cold weather inactivates them. In spring, winged females fly to suitable host plants and give birth to living young. Each female produces an average of 84 nymphs. Under favorable conditions, a nymph will mature in about five days and begin producing progeny. Most nymphs develop into wingless adults. However, when crowding occurs or food becomes scarce, winged adults develop and fly to new host plants. Reproduction continues through the winter but at a much slower rate than in summer. Many overlapping generations are produced each year.

Control

Predators such as lady beetles and their larvae, hover fly larvae, and aphid lion larvae reduce melon aphid populations. A small parasitic wasp, Aphidius colemani, is also an important natural control agent. Damp weather promotes a fungal disease that suppresses aphid populations, and hard, driving rains tend to kill large numbers of aphids.

Aphids can be controlled by cultural practices and insecticide applications. Planting in a well-prepared, fertile seedbed helps produce a vigorous crop better able to withstand aphid attack. Such a seedbed should not be located near an aphid-infested crop or on land from which an aphid-infested crop has recently been removed.

Apply insecticides if it becomes evident that natural and cultural controls are not keeping aphids in check. For up-to-date recommendations and rates, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Pickleworm and Melonworm

Pickleworm, Diaphania nitidalis (Stoll), Crambidae, LEPIDOPTERA

Melonworm, Diaphania hyalinata (Linnaeus), Crambidae, LEPIDOPTERA

Description

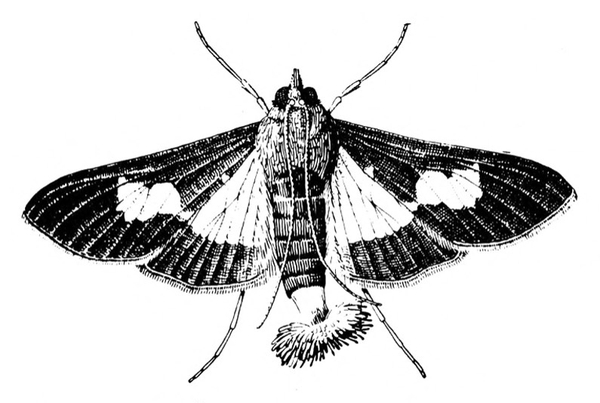

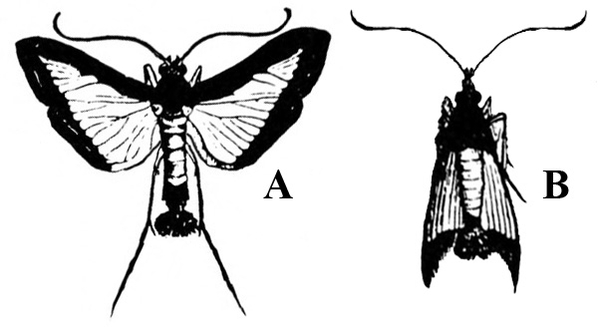

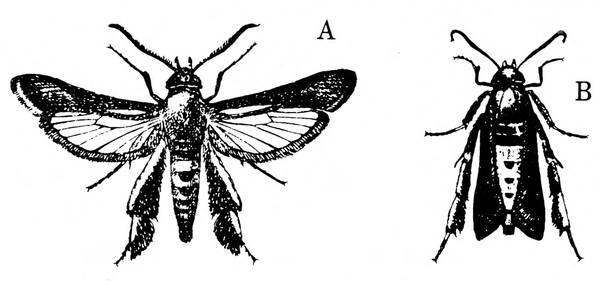

Adult—The pickleworm moth has a large, pale-yellow spot near the center of each dark-brown forewing; the pale-yellow hind wings have a wide, dark-brown border (Figure 21A). Its wingspan is about 1 1/4 inches. A cluster of dark, brushlike hairs is present on the tip of the abdomen. The melonworm moth has a brown head and a white-tipped abdomen with bushy, hairlike scales. Its white wings have a narrow, dark band around the margin and span up to 1 3/4 inches (Figure 21L).

Egg—The eggs of both species are similar. Deposited singly or in small clusters on the foliage (Figure 21B), the white eggs gradually turn dull yellow before hatching. Variable in shape, each egg is about 1/64 inch in diameter.

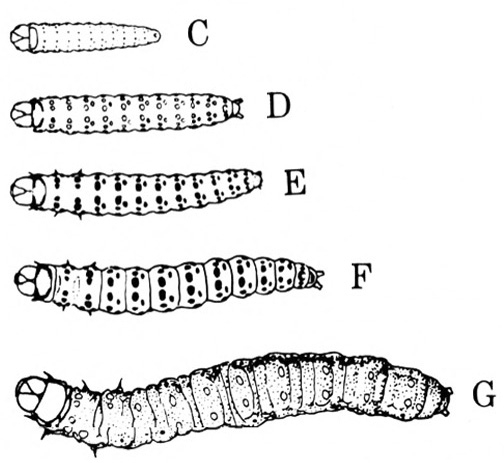

Larva—About 1/16 inch long, the newly hatched pickleworm larva is almost colorless except for slightly darker jaws and a black spot on each side of the head. Third- and fourth-instar larvae are about 1/4 to 1/2 inch long and are pale yellow with dark spots, each containing a large bristle. The dark-headed, fifth-instar larva has a yellow-green body with no spots and may be as long as 13/16 inch (Figure 21C–G).

The slender, greenish melonworm larva has two thin, white stripes down its back (with the exception of its first and last instars). It is 13/16 to 1 inch long when fully grown (Figure 21M).

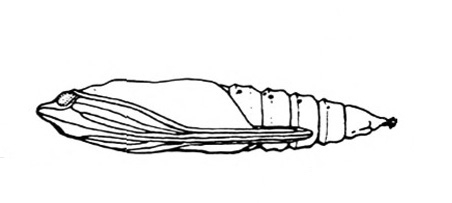

Pupa—Enclosed in a thin, silken cocoon, the white pupa turns reddish brown soon after forming. Pupae are about 5/8 inch long (Figure 21H and Figure 21N).

Biology

Distribution—The pickleworm has been reported from Canada southward into South America. In the United States, it is a year-round inhabitant of southern Florida. Each summer, the moth migrates to North Carolina, farther northward into Iowa and Connecticut, and westward to Oklahoma and Nebraska. The melonworm, however, is rarely found north of the Gulf states.

Host Plants—These two caterpillar species infest only cucurbits. Though the pickleworm prefers summer squash, it may also severely damage cucumber and cantaloupe. Pickleworm rarely damages watermelon, muskmelon, winter squash, pumpkin, or gourd. The melonworm prefers foliage of muskmelon, squash, cucumber, and pumpkin. It rarely attacks watermelon.

Damage—Unlike melonworms, which feed primarily on foliage, pickleworms cause important economic damage to fruit (Figure 21I). Young pickleworms usually begin feeding among small leaves at the growing tips of vines or within blossoms. A favorite place is the large staminate flower of squash, where larvae hide under the ring of stamens at the base of flowers (Figure 21J). When about half grown, pickleworms typically bore into fruits and stems and continue to feed, causing internal damage and producing soft excrement (Figure 21K). Pickleworms attack young and old fruits, but they prefer feeding on fruits before the rind has hardened. Infested fruit soon rots or—in the case of cantaloupes—sours. Heavily damaged vines stop growing.

Life History—Pickleworm moths migrate northward from Florida in the spring. They usually appear in the Raleigh, North Carolina, area by early July. They deposit eggs singly or in small clusters on hairy surfaces of plants. About three days later, young pickleworms emerge. After feeding for two weeks, larvae spin thin cocoons within rolled leaves and pupate. Five to seven days later, a new generation of moths emerges. In North Carolina, pickleworms complete two full generations and a partial third generation, if food is available and there is no early frost. The life cycle of melonworms is similar to that of pickleworms.

Control

In North Carolina, field experiments have shown distinct differences in susceptibility or resistance of cucurbit varieties to pickleworms. The most resistant winter squash varieties are Betternut 23, Buttercup, Boston Marrow, Blue Hubbard, and Green Hubbard. Gemini cucumbers; Edisto 47 cantaloupe and honeydew melons; Blue Ribbon and Crimson Sweet watermelons; and Green Striped Cushaw, King of the Mammoth, and Mammoth Chili pumpkins also show good resistance to pickleworms. Tests with insecticides have shown much better control of pickleworms on resistant varieties than on susceptible varieties.

Insecticide applications should begin immediately when pickleworms or signs of damage first appear. Planting a few plants of a susceptible squash variety should help growers detect the first appearance of pickleworms, especially the presence of caterpillars in flowers. Apply insecticides in late afternoon to minimize bee kills. For recommended insecticides and rates, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Squash Bug

Anasa tristis (DeGeer), Coreidae, HEMIPTERA

Description

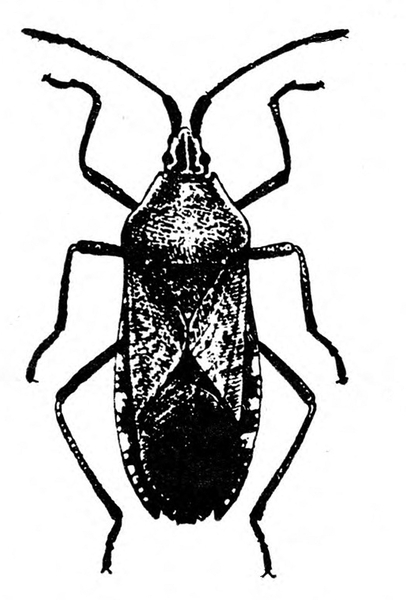

Adult—This hard, oval-elongate bug is dark brown, mottled with light gray on its back side, and mottled yellow on its underside (Figure 22A). About 5/8 inch long, it has a flat back. It gives off a bad odor when crushed. Typical of all true bugs, the mouthparts are needlelike.

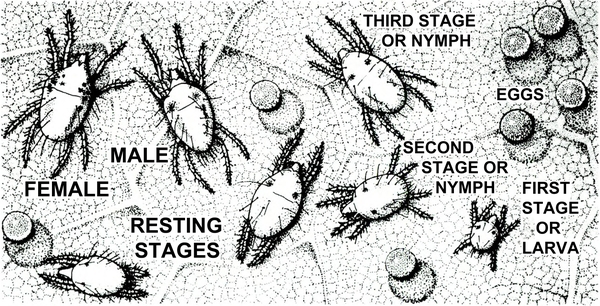

Egg—Roughly diamond- or spindle-shaped, each egg is white when first deposited but gradually turns yellowish brown and finally dark bronze. It is about 1/16 inch long. Eggs typically are laid on foliage in masses of 20 to 40 (Figure 22B).

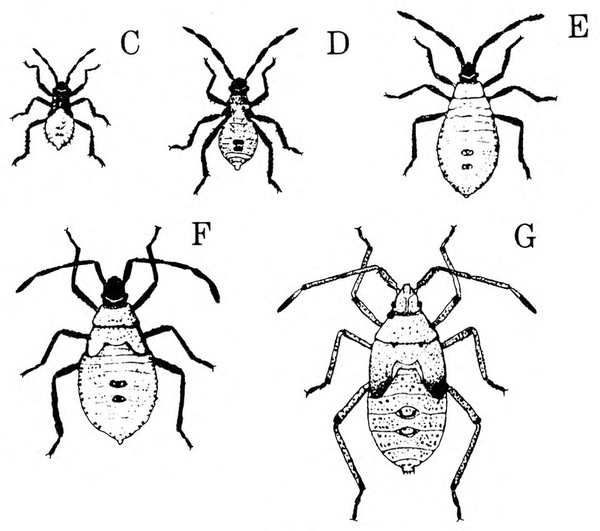

Nymph—The five nymphal instars range in length from almost 1/8 to 3/8 inch (Figure 22C–G). The first instar is green with rose-colored legs, antennae, and head. These appendages darken in a few hours. Subsequent instars are grayish white with dark heads, legs, and antennae. The last two instars have noticeable wing pads.

Biology

Distribution—Squash bugs occur from Canada into Central America and can be found throughout the United States. In vegetable gardens, they usually hide under leaves or around the bases of plants. These bugs characteristically shy away or move to cover when approached.

Host Plants—All cucurbit vine crops are subject to squash bug infestation. The bugs prefer squash, pumpkin, cucumber, and melon, in that order. Hubbard and marrow squash are often heavily infested.

Damage—Adults and nymphs feed in colonies, piercing vines with their needlelike mouthparts. While feeding, they inject a toxic substance into plants. As a result, vines quickly turn black and dry out. This aspect of squash bug damage superficially resembles bacterial wilt symptoms. Small plants and individual runners of large vines are often destroyed. When infestations are heavy, fruit may not form; if fruit does develop, bugs may congregate and feed on unripe fruit.

Life History—Squash bugs overwinter as unmated adults under plant debris or other suitable shelter. When cucurbit vines start to run in spring, squash bugs fly into gardens and mate. Over a period of several weeks, they lay eggs on the undersides of leaves, typically in the angles formed by leaf veins (Figure 22B). One or two weeks later, nymphs hatch from the eggs and begin to feed. Four to six weeks pass before nymphs develop into adults. Because of the prolonged egg-laying period, nymphs and adults are present throughout summer. Feeding continues until frost forces adults into hibernation. One generation occurs each year.

Control

Good cultural practices help prevent serious squash bug damage. For example, proper fertilization of vines produces a vigorous crop better able to withstand insect attack. The planting of resistant winter squash cultivars such as Butternut, Royal Acorn, and Sweet Cheese also reduces squash bug problems. Removal and destruction of crop debris after harvest eliminate some potential overwintering sites for squash bugs.

In small gardens, adult squash bugs and leaves with egg masses can be removed by hand and destroyed. The bugs can also be trapped under small boards placed near the host vines. Squash bugs gather under the boards at night and may be collected and destroyed the next morning.

Should a significant infestation develop, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual for current insecticide recommendations and rates.

Squash Vine Borer

Melittia cucurbitae (Harris), Sesiidae, LEPIDOPTERA

Description

Adult—The squash vine borer moth has forewings that are covered in greenish-black scales and hind wings that are clear with a brown border (Figure 16 and Figure 23A–B). The wingspan is 1 to 1 1/2 inches. The moth’s abdomen is ringed with orange and black stripes.

Egg—The tiny, brownish egg is oval and somewhat flattened (Figure 23C).

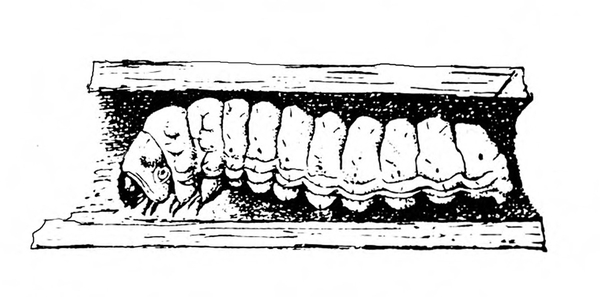

Larva—The larva has a wrinkled, whitish body, a brown head, three pairs of short legs near the head, and five pairs of prolegs on the abdomen (Figure 23D). Each proleg bears two transverse rows of tiny, curved spines known as crochets. The larva is about 1 inch long when fully grown.

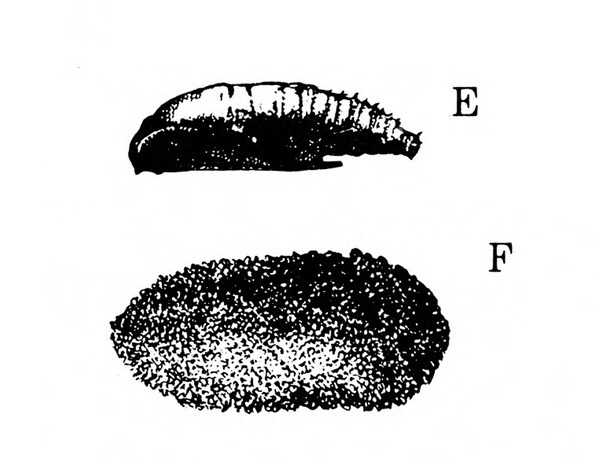

Pupa—About 3/4 inch long, the pupa is enclosed in a black, silk-lined cocoon in the soil (Figure 23E–F).

Biology

Distribution—This native pest ranges from southern Canada throughout the United States east of the Rocky Mountains and into South America.

Host Plants—Squash vine borers feed primarily on squash and pumpkin. Though they occasionally feed on other cucurbits like cucumber, watermelon, and muskmelon, the borers cannot complete their life cycle by feeding on those plants.

Damage—Damage first appears as sudden wilting of a long runner or an entire plant. Closer examination reveals masses of coarse, greenish-yellow excrement that the borer has pushed out from the stem. Splitting the stem where this damage appears may reveal the thick, white, wrinkled, brown-headed caterpillar inside (Figure 16). Borers are very destructive pests of squash and pumpkin in North Carolina. In commercial squash plantings, 25 percent or more of the crop can be damaged. Home gardeners suffer even greater losses, as infested vines are often completely girdled and usually rot and die. Squash vine borers enter vines near the soil and feed on inner tissues. Small borers may enter leaf stems but most often are found at the base of plants. Later, they may be found throughout stems and even in fruits. Sometimes vines are almost severed.

Life History—Squash vine borers overwinter as mature larvae or pupae within cocoons 1 to 2 inches deep in the soil. In April, moths emerge and fly swiftly and noisily around plants during the day. Throughout April and May, females lay single eggs on stems (Figure 23C) and leaf petioles. About one week later, borers emerge and tunnel into stems. After feeding for four to six weeks, larvae are fully grown. At this time, they leave their burrows, tunnel into the soil, and spin cocoons. Two or three weeks later, new moths emerge, giving rise to a second generation of larvae in North Carolina during August. Only two generations occur each year.

Control

Because the insect overwinters in the ground, do not plant squash where it has been grown the previous season. Disk land in fall to expose the cocoons, and plow deeply the following spring. Always destroy vines after harvest to prevent late caterpillars from completing their development. Sometimes pest injury can be prevented via late and staggered plantings and heavy fertilization to promote rapid growth. An egg parasite exists but doesn’t destroy significant numbers of borer eggs in most years. Hence, natural control is marginal at best.

To minimize damage, early detection of vine borers is critical. Should any wilting occur, check around the bases of plants for masses of excrement or signs of borer entry. In home gardens, it may be practical to remove borers by slitting infested vines with a sharp knife and then covering the injured areas with moist soil. Some gardeners routinely place a shovelful of soil at one or more locations along each vine to encourage plants to develop supplementary root systems; such plants overcome borer attacks more easily.

Chemical control can be effective if started at the first sign of an infestation. Because most insecticides are toxic to honey bees and other pollinating insects, apply chemicals in late evening (when those insects are not active) and at the bases of plants. For specific chemical recommendations and rates, consult the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual.

Other Resources

General

Hall, C. V., and R. H. Painter. Insect Resistance in Cucurbits. Technical Bulletin 156. Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station, 1968.

Harris, E. D. Insect Control on Cucumbers, Melons, Squash, and Pumpkins. Circular 566. University of Georgia Cooperative Extension Service, 1973.

Hughes, G. R., C. W. Averre, and K. A. Sorensen. Growing Pickling Cucumbers in North Carolina. Circular 593. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Agricultural Extension Service, 1974.

Michelbacher, A. E., W. W. Middlekauff, O. G. Bacon, and J. E. Swift. Controlling Melon Insects and Spider Mites. Bulletin 749. California Agricultural Experiment Station, Division of Agricultural Sciences, University of California, 1955.

Cucumber Beetles

Chittenden, E. H. The Striped Cucumber Beetle: How to Control It. Farmers' Bulletin 1322. USDA, 1923.

Da Costa, G. P., and C. M. Jones. “Resistance in Cucumber, Cucumis sativus L. to Three Species of Cucumber Beetles.” HortScience 6, no. 4 (1971): 340–42.

Evans, B. G., and J. M. Renkena. Common Name: Striped Cucumber Beetle, Scientific Name: Acalymma vittatum F. (Insecta: Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Featured Creatures. Publication Number: EENY–707. Entomology and Nematology, FDACS/DPI, EDIS, University of Florida, 2018.

Haynes, R. L., and C. M. Jones. “Wilting and Damage to Cucumber by Spotted and Striped Cucumber Beetles.” HortScience 10, no. 3 (June 1975): 265–66.

Houser, J. S., and W. V. Balduf. “The Striped Cucumber Beetle.” Ohio Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 388 (1925): 241–364.

USDA. The Southern Corn Rootworm—How to Control It. Leaflet 391. USDA, 1961.

White, R. E. Injurious Beetles of the Genus Diabrotica (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Entomology Circular 27. Florida Department of Agriculture, Division of Plant Industry, 1964.

Garden Fleahopper

Beyer, A. H. Garden Flea-Hopper in Alfalfa and Its Control. Bulletin No. 964. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1921.

Cagle, L. R., and H. W. Jackson. Life History of the Garden Fleahopper. Technical Bulletin 107. Virginia Agricultural Experiment Station, 1947.

Capinera, J. L. Common Name: Garden Fleahopper, Scientific Name: Microtechnites bractatus (Say) (Insecta: Hemiptera: Mirdae). Featured Creatures. Publication Number: EENY–78. Entomology and Nematology, FDACS/DPI, EDIS, University of Florida, 2017.

Knight, H. H. “Notes on the Distribution and Host Plants of Some North American Miridae (Hemiptera).” The Canadian Entomologist 59 (1927): 34–44.

Knight, H. H. “The Plant Bugs, or Miridae, of Illinois.” Illinois Natural History Survey Bulletin 22, nos. 1–7 (1943): 1–234.

Melon Aphid

Chittenden, F. H. Control of the Melon Aphis. Farmers' Bulletin 914. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture, 1918.

Isley, D. The Cotton Aphid. Bulletin 462. Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station, 1946.

Patch, E. M. “The Melon Aphid.” Maine Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 326 (1925): 185–96.

USDA. The Cotton Aphid: How to Control It. Leaflet 467. USDA, 1960.

Melonworm

Capinera, J. L. Common Name: Melonworm, Scientific Name: Diaphania hyalinata Linnaeus (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Featured Creatures. Publication Number: EENY–163. Entomology and Nematology, FDACS/DPI, EDIS, University of Florida, 2017.

Pickleworm

Canerday, T. D., and J. D. Dillbeck. The Pickleworm: Its Control on Cucurbits in Alabama. Bulletin 381. Auburn, AL: Agricultural Experiment Station, Auburn University, 1968.

Dupree, M., T. L. Bissell, and C. M. Beckham. “The Pickleworm and Its Control.” Georgia Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 5 (1955): 1–34.

Fulton, B. B. Biology and Control of the Pickleworm. Technical Bulletin 85. North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station, 1947.

Harris, E. D. Pickleworm. Leaflet 84. University of Georgia Cooperative Extension Service, 1973.

Reid, Jr., W. J., and F. J. Cuthbert, Jr. The Pickleworm: How to Control it on Cucumber, Squash, Cantaloupe, and Other Cucurbits. Leaflet 455. USDA, 1966.

Squash Bug

Chittenden, R. H. “Life History of the Common Squash Bug.” USDA Division of Entomology Bulletin 19 (1899): 20–28.

Hoffman, R. L. The Insects of Virginia No. 9: Squash, Broad-Headed, and Scentless Plant Bugs of Virginia (Hemiptera: Coreoidea: Coreidae, Alydidae, Rhopalidae). Research Division Bulletin 105. Blacksburg, VA: Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 1975.

Squash Vine Borer

Howe, W. L. “Biology and Host Relationships of the Squash Vine Borer.” Journal of Economic Entomology 43 (1950): 480–83.

Howe, W. L., and A. M. Rhodes. “Host Relationships of the Squash Vine Borer, Melittia cucurbitae with Species of Cucurbita.” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 66 (1973): 266–69.

Publication date: June 11, 2024

AG-295

Other Publications in Insect and Related Pests of Vegetables

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.