Wildlife and Forest Stewardship

If you enjoy wildlife watching, hunting, fishing, hiking, camping, horseback riding, or any other outdoor recreational activity, you are not alone. Millions of Americans spend time outside in pursuit of outdoor recreation. If you are a landowner interested in managing your forested land for wildlife, you are in a unique position to benefit not only yourself, but also some of the many wonderful plants and animals that call North Carolina home.

Developing forestland to produce timber, protect soil and water quality, and provide habitat for desired wildlife requires an active management plan. Forest stewardship, the process of managing all of the forest’s natural resources together, enables people to conserve forest resources, including timber, wildlife, soil, and water. Forestry and wildlife management are not only compatible, they are interrelated. Managed forests provide higher quality habitat for wildlife than unmanaged forests, and management for white-tailed deer, wild turkey, and other wildlife species can also produce quality timber. This publication describes the basic concepts of forest management, showing how forestry operations affect food and cover resources for wildlife.

Understanding Wildlife's Link to the Forest

Habitat loss is the greatest threat to wildlife conservation. Landowners can manage forestland to maintain and even create essential habitat for various species of wildlife. Understanding the relationship between wildlife and your woodlands is critical to learning the necessary steps to improve habitat on your property. With planning and appropriate management, you can favor the animals and plants you most desire on your property.

Wildlife have four basic requirements: food, cover, water, and space to live and raise their young. Different wildlife species require different types of food and cover and different stages of plant succession to meet their basic needs. Variations in plant composition and structure, forest age, and soil productivity determine the type and number of wildlife species present on a property. Although there are a few examples of old-growth forest in North Carolina, the majority of North Carolina’s forests developed from abandoned farmland or regenerated after timber harvests in the early to mid-1900s.

Evaluating Your Property

An aerial photograph will offer a complete view of the land uses and vegetative cover within your property boundaries and on adjacent properties. This bird’s-eye view can help you identify water sources, fallow fields and cropland, forest stands, and wetland areas, and allow you to evaluate their arrangement on your property and surrounding land. Aerial photographs of your property should be available from Google Earth or your county tax office.

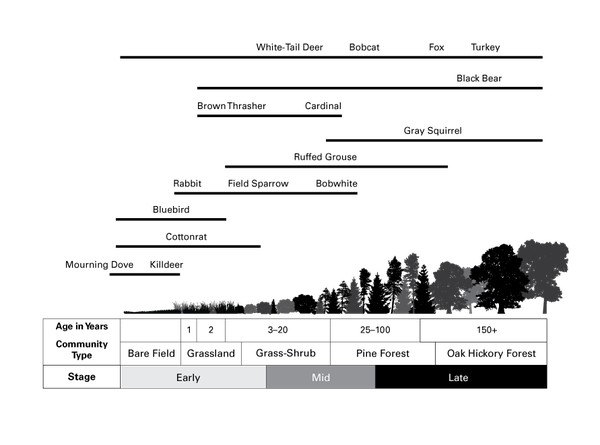

Succession

At some time in the past at least some of your forestland may have been farmland. If you have older aerial photographs of your land, you may be able to see the progression of abandoned farm fields from grasses and forbs to pole-sized timber and eventually mature timber. This progression from bare ground to mature forest is known as plant succession. Plant succession begins on bare ground with light-seeded grasses and forbs. Over time, shade-intolerant trees, shrubs, and brambles (blackberry) shade out the sun-loving herbaceous plants. Ultimately, more shade-tolerant tree species, including oaks and hickories, replace the shade-intolerant plants. Each of these stages of succession is called a seral stage, which is defined by compositional differences. The changes in plant composition and structure that occur through succession lead to changes in habitat availability for wildlife (Figure 1).

The vegetation conditions within a seral (successional) stage can be altered through management (think harvest, burning, and preparing a site for a new forest). In turn, these changes to the plant community create, degrade, or alter habitat for specific wildlife species on your property. For example, timber harvesting followed by intensive site preparation alters the plant community from a late to an early seral stage. Harvesting alone, especially in hardwood forests, only changes the structure within the same seral stage because the roots of the trees typically sprout back after the harvest. Tillage in a fallow crop field prevents succession by trees and keeps the plant community in an early seral stage. Low-intensity prescribed burning in the understory of forested woodland doesn’t change the seral stage, but it does reduce midstory development and promotes a diverse understory of grasses, forbs, and woody plants. Without any management or natural disturbance, fallow fields, shrubland, and young forest will naturally succeed into mature forests, and the habitat conditions for wildlife will change dramatically over time.

| Successional Stage | Plant Characteristics | Associated Wildlife* | Forest Practices to Promote this Seral Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early | Grasses, legumes and other forbs, brambles | Bobwhite quail, mourning dove, white-tailed deer, black bear, wild turkey, grassland songbirds, shrubland songbirds, cottontail rabbit | Clearcutting, controlled burning, disking, mowing |

| Middle | Shrubs, shade-intolerant trees | Ruffed grouse, white-tailed deer, black bear, shrubland songbirds | Pre-commercial or commercial thinning, regeneration harvests, controlled burning |

| Late | Shade-tolerant trees, snags and downed logs, den trees | Gray squirrel, raccoon, white-tailed deer, black bear, ruffed grouse, wood duck, wild turkey, forest songbirds | Group selection cuts, controlled burning |

* Animals that are listed in two or more successional stages use a mixture of seral stages. ↲

For example, bobwhite quail and pileated woodpeckers correspond to different stages of plant succession. Quail feed on seeds from annual and perennial herbaceous plants and seek out woody understory plants for cover from predators and harsh weather, making them an obligate of early seral stages. Therefore, if you want to promote quail populations, emphasize regeneration harvests, commercial thinning, and controlled burning. Pileated woodpeckers, on the other hand, depend on large diameter dead or dying trees found in mature forests for their food and nesting sites. If you want to promote populations of pileated woodpeckers, emphasize mature forests containing snags.

Land managers can create a diverse habitat by mixing timber stands of various ages with open areas.

Developing Your Forest Stewardship Plan

Once you understand the relationships between the kinds of wildlife you want to attract, the target species’ ecological needs, the individual characteristics of your land, and your available resources, you can develop a forest stewardship plan.

Begin the plan with a list of goals and objectives. Goals are broader in nature, while objectives are more focused and specific. For example, your goal may be to see more wild turkeys on your property, so objectives to help meet that goal would include improving habitat for brooding, nesting, and roosting, minimizing disturbance during the nesting season, and increasing harvest selectivity. The more specific your objectives, the easier they are to achieve and measure. For example, improving habitat for turkey brooding might translate to converting five acres of tall fescue cattle pasture into a fallow field that contains at least 40 species of native grasses, forbs, or legumes, most of which will flower throughout the spring and summer (during nesting and brood rearing season) to attract a diversity of insects (prey) for turkey poults. It is important to include all your land management goals and objectives into your stewardship plan, including, but not limited to, wildlife, timber, aesthetic, and recreational goals; many uses will be compatible and can be worked on simultaneously, while others will involve trade-offs. Make your goals and objectives realistic and attainable given your physical and financial capabilities. Some improvements and practices are inexpensive, while others may require substantial investments of labor or capital.

Wildlife biologists, agency foresters, soil conservationists, extension agents, and forestry consultants can help you define or refine your goals and objectives and help you create (or develop for you) a forest stewardship plan for your property. They can also help you identify your resources, evaluate alternatives, develop a written framework and, in some cases, supervise management operations.

Over time, your objectives may change. A well-designed plan will be flexible enough to accommodate changes in goals, markets, and the overall economy. Plan carefully from the start, but treat the plan as a living document, making adjustments for the future as your interests, resources, and needs change. For additional information on forest stewardship, see Enrolling in North Carolina’s Forest Stewardship Program (WON-23), available from your local county N.C. Cooperative Extension center.

Wildlife-Friendly Forest Management Practices

Managing your forest resources requires an understanding of various forestry systems and their effects on wildlife. When left completely untouched, forests experience natural disturbances from wildfires, floods, tornadoes, insects, diseases, and earthquakes. After a tornado, for instance, affected areas in a forest will have different structural characteristics than unaffected areas. Insects and diseases, for example, cause openings in the forest that allow more sunlight to reach the ground. Forest management practices often simulate natural disturbances. You can use these practices to manipulate the forest to improve habitat for focal wildlife species.

The goals and objectives outlined in your management plan, along with the characteristics of your property, determine which forest management systems to use. Each system benefits different groups of wildlife, and you can use just one or any combination of systems. The following is a basic introduction to the most common forest management systems.

Even-Aged Management

An even-aged system creates a stand of trees that are all approximately the same age. Usually all the trees in a given area are harvested at one time or in several cuttings over a short time to keep the stand approximately the same age. This method is especially common in harvesting or managing sun-loving trees like the loblolly pine and some hardwoods like the yellow-poplar.

Hardwood stands often appear to be uneven in age because the trees vary in size. It is not uncommon to find an oak 8 inches in diameter growing beside one that is 16 inches in diameter. Although the trees are the same age, the smaller tree may not have grown as rapidly as the larger one because it received less sunlight, nutrients, and water.

Even-aged forests can be regenerated through three harvesting practices: clearcutting, shelterwood cutting, and seed-tree cutting. These practices can benefit wildlife species that require more open forest or shrubland (Table 2). See Developing Wildlife-Friendly Pine Plantations (WON-38) for more information on managing for wildlife using even-aged regeneration methods.

| System | Sunlight | Canopy | Wildlife Favored | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clearcut | Full | None |

Early successional species that feed on annual and perennial plants, shrubs, and insects. Also birds of prey. Sites that are recently harvested, regardless of method used, tend to have more dense understory, more soft mast production, and more browse for deer. The two retention methods, especially shelterwood harvests, have the added benefit of retained overstory structure and production of mast (usually hard mast) from the trees. The wildlife that benefit are shrubland birds, woodland birds, white-tailed deer, cottontail rabbit, bobwhite quail, and black bears. Grouse eventually benefit as the regenerating stems grow into the midstory. |

|

| Seed-tree | Full | Sparse; individual trees | ||

| Shelterwood | Partial | Partially open | ||

Clearcutting is a method of harvesting and regeneration that removes all trees within a given area. Used most frequently to regenerate pines and hardwood species that require full sunlight for growth, this method simulates a major natural disturbance and creates young forest. If intensive site-preparation practices (for example, herbicide application, shearing, or root raking) follow the harvest, the plant community shifts to an early successional stage that is dominated by grasses, forbs, and brambles. With no site preparation, hardwoods often sprout back quickly as part of a young forest.

The size and arrangement of management areas will influence food and cover for wildlife while dictating economics of future actions and harvests in particular. Leaving patches of uncut timber or retaining individual trees within clearcut harvests will enhance wildlife habitat by maintaining some overstory structure and mast, if the overstory trees are appropriate. Try to maintain old trees with visible cavities that can be used by wildlife.

Shelterwood cutting clears trees in two or three cuts over several years, resulting in a stand of trees that are nearly the same age. Regeneration of intermediate shade-tolerant species, including many species of oaks, is possible when a “shelter” is left to protect them from too much or too little light. Shelterwood harvests provide food and cover conditions similar to clearcutting, though the partial retention of overstory has added benefits for canopy-dwelling wildlife, species that use tree dens, and wildlife that consume the mast from retained overstory trees.

Shelterwood cutting typically involves more planning from resource professionals and higher logging costs than clearcutting. Also, the chance for soil disturbance and tree regeneration increases with repeated stand entry.

Seed-tree harvesting commonly is used to regenerate light-seeded pine species that produce frequent seed crops. In a seed-tree harvest, several mature trees are left standing to seed the next stand of trees.

The proper selection of seed trees is critical. Foresters should select seed trees that are well spaced, windfirm, vigorous, sound, and of good form and quality. Mark trees clearly to avoid accidental removal and damage during the regeneration cut. The benefits to wildlife are nearly the same as with the clearcutting system, with the exception of the seed trees. If left indefinitely, the seed trees eventually can become snags or downed logs that are important habitat for woodpeckers and many other wildlife species. Seed trees are also excellent perching or nesting sites for hawks and other birds. For additional information on seed distribution for particular trees, contact your local N.C. Cooperative Extension center or your local forester. See also Working with Wildlife 14, Snags and Downed Logs.

The seed-tree method is low cost at the onset, with some five or six trees per acre left on site (removed from the sale process). While seed trees create a pleasant appearance, the true cost of this harvest method can rise as seed trees are lost to lightning and possibly wind. Landowners may enjoy the second harvest payment when the seed trees are removed after regeneration. However, seed-tree harvests typically require some additional investment for precommercial thinning and competition control.

Uneven-Aged Management

An uneven-aged system maintains a timber stand with more than two age classes of trees, either through cutting of selected groups of trees or cutting of individual trees. This regeneration system simulates minor natural disturbances such as windthrows, insect and disease damage, or spot wildfires. Succession is held at the mid- to late-successional stage. Uneven-aged regeneration methods benefit wildlife associated with closed canopy forests or small canopy gaps in the forest (Table 3).

| System | Sunlight | Canopy | Wildlife Favored |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-tree selection | Partial | Partial | Gray squirrel, forest-breeding songbirds, many woodpeckers, salamanders |

| Group selection | Openings: full

Remainder: filtered |

Openings: none

Remainder: closed |

Gray squirrel, forest-breeding songbirds, many woodpeckers, salamanders. Group selection provides openings for some shrubland songbirds like indigo bunting, and patches of browse and cover for white-tailed deer and eastern cottontail. |

Group selection involves the harvest of groups of trees over many years until eventually — for example, 80 to 100 years later — the entire stand has been cut. Each cut is a small-scale opening in an area of two acres or less. Group selection produces high-quality, veneer-grade hardwoods that may bring top dollar when sold. This method is used primarily on bottomland or upland hardwoods.

Group selection cuts provide pockets of young forest for ruffed grouse, American woodcock, white-tailed deer, and songbirds. Note that this practice requires intensive management and frequent access to all areas of the property. For these reasons, group selection may be feasible only where high-value trees exist on accessible sites.

Single tree selection is the harvest of individual trees to create low light levels that favor regeneration of shade-tolerant species such as American beech and sugar maple. Single tree selection keeps the stand in a perpetual state of late succession that favors wildlife associated with mature forest. Unless single tree selection removes irregular, low-quality trees along with merchantable timber, this management system will gradually reduce the value of the timber on your property. Single tree selection requires frequent harvesting that is costly, unless conducted by the landowner. The slower-growing, shade-tolerant species favored by this method are not commercially desirable in North Carolina and the southeastern United States, so the method typically is not used to regenerate forests.

Reforestation

Part of choosing a forest management system is planning for the future growth of the stand. Two basic methods of reforestation are natural regeneration and artificial regeneration.

Natural regeneration, as the name implies, relies on nature to provide the seeds to start a new stand of trees. If you set the proper conditions at and before harvest, you can anticipate new, vigorous growth with little cost. Natural regeneration is most appropriately used with seed-tree cut, shelterwood cut, single tree selection, and group selection systems (Table 4).

Artificial regeneration includes seeding and planting. By planting seedlings you can choose the species, genetic quality, and spacing of your future stand. Although this process requires a capital investment, the result is a more productive stand in a shorter period. Artificial regeneration is commonly used after clearcutting or is used experimentally with oak seedlings after group selection (Table 4).

More information is available in Steps to Successful Pine Plantings (WON-16); Reforestation of North Carolina’s Pines (WON-9); and Developing Wildlife-Friendly Pine Plantations (WON-38) at the NC State Extension publications website.

| Management systems | Natural regeneration | Artificial regeneration |

|---|---|---|

| Even-aged | Seed tree cut

Shelterwood cut |

Clearcut |

| Uneven-aged

|

Single-tree selection

Group selection |

Patch plantings

(oak or longleaf seedlings are common) |

Forest Operations That Benefit Wildlife

Depending on your goals, a number of additional forest operations can help you achieve your wildlife and forest management objectives.

Thinning operations in a stand are prescribed by foresters to increase the growth rate of the best trees, to provide for periodic income, to harvest trees before they die, and to promote forest health and vigor. The remaining trees grow better because light, moisture, and soil nutrients are more readily available. Understory growth is improved because of the increase in sunlight penetration of the forest floor. Thinning alters the structure of the vegetation within mid- to late-seral stages, notably shifting plant biomass from the canopy and the midstory to the understory. Deer, quail, and rabbits have more food and cover in the understory. Therefore, thinning operations can be managed in a way that enhances both timber production and wildlife habitat quality. For additional information on thinning, see Thinning Pine Stands (WON-13).

Prescribed burning is a forestry operation that helps reduce the risk of wildfire and the costs of preparing harvested areas for tree planting. Burning can maintain early successional plant communities or shift the structure and composition of the understory and midstory of mid- and late-succession forests. However, prescribed burning has the most beneficial effects in forests where the canopy is relatively open and some light is reaching the forest floor.

The effects that prescribed burning has on the plant community depend on the intensity, timing, and frequency of burning, among a number of other environmental factors. Frequent burning keeps tree sprouts from moving into the midstory; in turn, the reduction in woody cover and the periodic reduction in the leaf litter layer increase seed germination and persistence of herbaceous vegetation, including legumes and grasses. Prescribed burning also increases the nutritional value of deer browse for the month following fire. For more information, see Using Fire to Improve Wildlife Habitat (AG-630).

Prescribed burning may also promote the development of oaks in hardwood forests. Much of the predominantly oak forest present today is thought to be a result of repeated fires, grazing, and cutting practices throughout the past 200 years. A prescribed fire in a hardwood stand kills the undesirable, thin-barked tree species, such as red maple, and gives the oaks a chance to develop and dominate the stand.

Before you initiate any prescribed burns on your property, review rules and regulations from the North Carolina Forest Service and enroll in the Certified Burner Class. Through this program, you can learn how to conduct prescribed burns safely and legally to remove undesirable vegetation and enhance wildlife habitat in your forest. You may also obtain information from your local N.C. Cooperative Extension center.

Den Trees and Snags. Regardless of the harvest system you use, consider the potential of den trees and snags on your land before you begin harvesting.

Den trees are live trees that have one or more hollow chambers that are used by birds, mammals, and reptiles for nesting, roosting, and hibernating. Dead, standing trees are called snags and often contain cavities created by woodpeckers or other wildlife that can be used for nesting, roosting, hibernating, and escape cover for a variety of wildlife. As a general rule, two to four den trees or snags per acre should be maintained throughout the property. Den trees or snags can be as small as 5 inches in diameter or as large as 5 feet in diameter. The smaller diameter trees may house chickadees, woodpeckers, screech owls, or flying squirrels, while the larger trees may house raccoons or occasionally a bear. If suitable den trees or snags do not exist in your woodlands, you can create snags or install constructed boxes or nests to offer alternatives for cavity-nesting wildlife (see Working with Wildlife: Building Songbird Boxes; Snags and Downed Logs; and Woodland and Wildlife Nest Boxes).

Mast Tree Selection. Mast-producing trees provide fruits and nuts for wildlife food. Try to retain these trees where possible during timber harvesting activities. Some trees produce hard mast, like nuts and acorns, while other trees produce soft mast, like berries and drupes. Although some of these mast-producing trees, such as American beech, hawthorn, and sourwood, are not highly valued species for wood products, they produce important wildlife food. Grapevines also are important mast producers, but the vines can deform your hardwood timber and reduce its value, and they need sunlight to produce grapes. Concentrate wild grapes on arbors, brush piles, or riparian areas where timber objectives are secondary.

Making wildlife objectives known to the professionals is key to planning. Be sure to reiterate your objectives prior to timber harvest or other forest management operations. Specify that mast trees, den trees, and snags be left whenever possible. Wildlife management activities do not have to be expensive, but they must be planned before you harvest any timber.

Road Construction and Maintenance. Whether you enter the woods for management or recreational purposes, easy, reliable access to your property is essential. Proper location, design, and construction of roads increase the value of forest property and reduce upkeep and costs. Multiple benefits can be gained from roads having good drainage, good construction, and the application of best management practices (BMPs), which are standards that minimize soil erosion and maintain water quality.

One practice that benefits wildlife and improves roads is known as daylighting. In this process, trees bordering access roads are removed to maximize the amount of sunlight that reaches the road surface and side banks. Sunlight enhances the growth and proliferation of shrubs, grasses, and forbs that provide food and cover for wildlife, while also drying the road surface. To reduce erosion, seeding may be required along steep roads and skid trails.

Summary

Wildlife management opportunities abound for private landowners in North Carolina. Forestry operations can be used to provide and enhance wildlife habitat, and information is available to help you get started right away. Talk to your local N.C. Cooperative Extension agent about publications and technical assistance. Cost-share assistance is also available to help landowners manage their forestland for multiple benefits, including wildlife and other resources. Forest stewardship management can be effective and rewarding for you and the generations to come.

Publication date: Dec. 4, 2019

Reviewed/Revised: Sept. 11, 2024

WON-27

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.