Outline

Ways Volunteer Educators Can Help

Steps to Creating a Successful Community Garden

Asset Based Community Development

Key Components of a Successful Mentor/Consultant Program

References and Further Reading

Objectives

After reading this chapter you can:

- Explain the role of a volunteer educator in a community, youth, or therapeutic garden.

- Identify effective steps to start and sustain a successful group garden.

- Develop specific strategies for record keeping and evaluation in group gardens.

Introduction

Unlike the other chapters in this handbook, this chapter will not provide extensive information on how to garden. Instead, we focus here on how to serve as an effective educator, coach, and mentor to others in three primary arenas: community gardens, youth gardens, and therapeutic gardens.

Community Gardens (Figure 21–1). These gardens are generally organized as either plot gardens or cooperative gardens. Some community gardens, however, are a combination of both plot and cooperative areas. Plot gardens subdivide the land into family-sized plots—ranging in size from 100 to 500 square feet—where each individual (or family) gardens in their own plot. Sometimes a section of the garden is reserved as shared space to grow crops too large for individual plots (such as corn, pumpkins, watermelons, fruit trees, grapes, and berries). Gardeners divide the bounty from these shared plots.

In a cooperative garden, the entire space is managed as one large garden through the coordinated efforts of many community members. Produce from the garden is sometimes distributed equitably to all the member gardeners. Often, however, these cooperative gardens are associated with communities of faith, civic groups, or service organizations that donate part or all of the produce to charitable organizations such as food banks and soup kitchens.

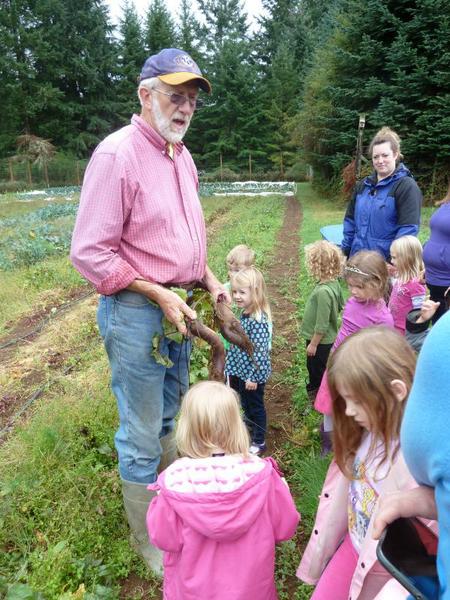

Youth Gardens (Figure 21–2). With the increasing interest in science and nutrition education, many schools and youth organizations in the United States are planting gardens to serve as outdoor learning laboratories. In the garden, everyone is transformed into a scientist, actively participating in research and discovery. Besides providing a motivating, hands-on setting for teaching skills in virtually every basic subject area, the garden is a wonderful place to learn responsibility, patience, pride, self-confidence, curiosity, critical thinking, and the art of nurturing. In schools, raised-bed gardens, or sections of the school landscape, are customarily assigned to classes. Hands-on curricula and activities are selected to supplement and support the standard course of study for science and nutrition for specific grade levels. In some cases, school gardens require extensive volunteer support so that classes may be split into small groups of children to work in the garden.

Therapeutic Gardens (Figure 21–3). Still other gardens focus on horticultural therapy: using plants to improve the social, educational, psychological, and physical well-being of the gardeners and their caregivers, family, and friends. Located in hospitals, nursing homes, assisted living facilities, retirement communities, outpatient treatment centers, botanical gardens, and other settings, therapeutic gardens are generally designed to be accessible to people with physical limitations. Therapeutic gardens may be designed for active gardening programs or as quiet spaces for reflection. These gardens may include raised beds and firm pathways to provide access to participants in wheelchairs, Braille signage for gardeners with sight impairments, special ergonomically designed tools for gardeners with limited physical strength, and other helpful accommodations. Therapeutic gardens are often designed with plant material selected for texture, color, sound, taste, and scent to appeal to all five senses.

Figure 21–3. Therapeutic gardens often use raised beds with high sides for those who have trouble bending or are in wheelchairs.

Gloria Polakof CC BY 2.0

Ways Volunteer Educators Can Help

Volunteer educators can support all three kinds of gardening programs by sharing information, providing resources, promoting communication, supporting fund development, encouraging volunteer management, facilitating community development (connecting to community partners), teaching the value of record keeping, and assisting with evaluation. Some of the topics volunteer educators might cover include composting, pest management, soil stewardship, food safety, nutrition, and health.

“A good organizer (as well as a good facilitator) provides the framework and structure for groups to flourish.”

(Abi-Nader, Dunnigan, and Markley, 2001)

The following lists describe ways that volunteer educators can support gardening programs. These activity suggestions reflect both volunteer experiences with gardening programs and the latest research about what makes a gardening program succeed or fail. See the References and Resources list at the end of this chapter for further reading.

Share Information

- Building exhibits

- Giving talks (Figure 21–4)

- Hosting workshops

- Visiting sites

- Consulting, mentoring, or coaching

Provide Resources

- Developing publications, such as online or printed newsletters and websites

- Growing vegetable transplants (Figure 21–5)

- Setting up a tool “lending library” (Figure 21–6)

- Supporting soil testing (including interpretation of results)

- Consulting regarding garden design

- Designing a water collection system (Figure 21–7)

- Managing a community garden library

- Growing gardens seed bank

- Emailing tips on specific problems during the growing season

- Assisting with fund development, including grant writing

Promote Communication, Networking, and Public Relations

- Creating bulletin boards (Figure 21–8)

- Developing a directory of gardens

- Promoting the garden through social media

- Helping to coordinate tours (Figure 21–9)

- Assisting with planning effective meetings

- Soliciting positive media attention

Support Fund Development

- Assisting with a clear vision, mission statement, budget, business plan, and elevator speech

- Pointing groups in the direction of where to look for in-kind gifts

- Eliciting donations (individual, corporate, crowdfunding online)

- Establishing fees

- Planning and coordinating events (plant sales, silent auctions, educational and social events) (Figure 21–10)

- Applying for grants—from writing a proposal through implementation

Encourage Volunteer Management

- Recruiting volunteers

- Tracking volunteers and potential contacts (contact information, service organizations)

- Communicating with volunteers (bulletin board, listserv, gatherings, written schedule of events)

- Encouraging positive feedback and recognition

American Community Gardening Association

Growing Communities Principles

- Engage and empower those affected by the garden at every stage of planning, building, and managing the garden project.

- Build on community strengths and assets.

- Embrace and value human differences and diversity. Promote equity.

- Foster relationships among families, neighbors, and members of the larger community.

- Honor ecological systems and biodiversity.

- Foster environmental, community, and personal health and transformation.

- Promote active citizenship and political empowerment.

- Promote continuous community and personal learning by sharing experience and knowledge.

- Integrate community gardens with other community development strategies.

- Design for long-term success and the broadest possible impact.

Core Beliefs of Community Garden Organizing

- There are many ways to start or manage a community garden.

- In order for a garden to be sustainable as a true community resource, it must grow from local conditions and reflect the strengths, needs, and desires of the local community.

- Diverse participation and leadership, at all phases of garden operation, enrich and strengthen a community garden.

- Each community member has something to contribute.

- Gardens are communities in themselves, as well as part of a larger community.

(Abi-Nader, Dunnigan, and Markley, 2001)

Figure 21–5. A garden mentor can help by growing transplants to be used in a youth, community, or therapeutic garden.

Lucy Bradley CC BY 2.0

Figure 21–6. A tool lending shed allows garden workers to check out tools, use them and put them back. This saves money as well as time and effort carrying tools to the garden each day.

Lucy Bradley CC BY 2.0

Figure 21–7. A colorful rain barrel collects water from the tool shed roof and provides a free water source for the garden.

Tim Mathews CC BY 2.0

Figure 21–8. A bulletin board allows gardeners to communicate with each other and the community.

Tim Mathews CC BY 2.0

Steps to Creating a Successful Community Garden

Community gardens come in all shapes and sizes and can be found in neighborhoods, private yards, parks, schoolyards, places of worship, or even on rooftops. The tasks of establishing and maintaining a successful community garden require a dedicated group of people with common interests and goals.

“Community organizing is successful when a community has taken charge of the process and project.”

(Abi-Nader, Dunnigan and Markley, 2001)

How do volunteers go about organizing a community garden for success? The following 10-step approach is based on the latest research about successful community gardens.

1. Set an informational meeting. Invite any interested parties—including neighbors, tenants, maintenance personnel, or local garden groups. Determine if a garden is needed and wanted by the group and set criteria for the garden. Will it be a community-maintained plot and harvest, or will individuals maintain their own plots and harvest their own crops? What are the criteria for who can be a member of the garden (such as must live within walking distance)? Will there be any fee associated with the garden? Can flowers be grown or just vegetables? Is this an organic garden? How will excess produce be distributed—to other neighbors or to local food banks? Will there be community tools, and where will they be stored? How do volunteers go about organizing a community garden for success? The following 10-step approach is based on the latest research about successful community gardens.

2. Create committees. Dividing the group into committees helps distribute work and ensure that the garden criteria list becomes a reality. Not all of these committees are necessary to a successful garden. A Planning Committee composed of dedicated, organized, and enthusiastic members will take the wish list and help guide the group in making the garden a reality. A Communications Committee will include tech-savvy group members who can help with a website or blog, newsletter, flyers, and signage, and will keep the group up-to-date about the latest garden happenings. A Construction Committee should be formed of able-bodied group members who are willing and able to move dirt and mulch, erect fences, and create garden beds. A Funding and Partnership Committee will be comfortable asking for help from the community, whether it is in the form of writing grants or asking for community support from local vendors. This committee may also identify the people and organizations in the community who would be good garden partners because of benefits to the garden and the partner.

3. Assess assets and identify resources. Conduct an asset assessment by interviewing all members of the group to discover skills and knowledge within the group that can be leveraged to build and maintain a garden. Identify city contacts, those who could help in locating a garden site or handle questions about irrigation or zoning. Contact local garden groups and the county Extension Center for access to gardening experts. See Appendix H for sample asset assessment forms.

4. Identify financial needs. The Funding and Sponsorship Committee can help create a budget that outlines the funding needed to make the garden a reality. Money may be needed to purchase or rent space and for tools, seeds, and garden construction materials (such as soil amendments, mulch, fencing, lumber). Approaching a community sponsor may be a way to get a large donation. Applying for garden grants is another option. Requiring a fee to garden may provide some long-term income, but usually a large sum is needed up front. Hosting a fundraiser in the community can produce a large income in a short period of time. A plant sale, garden dinner, or selling fence posts or bricks imprinted with sponsors’ names are some ideas.

5. Choose the site. Choosing the right site is extremely important. Is the land available, and can the group get a lease from the owner for at least five years? If the garden will grow vegetables, six hours of sunlight minimum is needed. A soil test should be completed (see chapter 1, “Soils and Plant Nutrients”) to make sure the plot has suitable nutrients for growing vegetables and to get recommendations for needed nutrients. Is the site close enough that garden members can access it easily? Is there access to water (Figure 21–11)? Can tools be stored in a secure location? Will liability insurance be necessary?

6. Develop the site. Most plots need quite a bit of work to be transformed into a vibrant garden. Have the Construction Committee organize work parties to help remove debris and weeds, and amend the soil.

7. Design the garden. The Planning Committee can put the final touches on the garden’s design, including how it will be divided, where pathways will be through the garden, water access, compost bins, tool storage, and signage (Figure 21–12). Consider planting a border of shrubs and perennials that give a tidy appearance that pleases neighbors and city code enforcers—even when the garden is resting for the winter.

8. Plan for children. A garden, no matter what its size, is a magnet for children. It is also a wonderful way to introduce young people to the magic of growing plants and where their food comes from (Figure 21–13). Creating a space or plot just for children allows them to experiment and experience the joy of gardening (Figure 21–14). When everyone feels a sense of pride and ownership in the garden, theft and vandalism are greatly reduced.

9. Finalize rules and put them in writing. Having the entire group create the ground rules ensures compliance. Making sure everyone in the group is on the same page and knows what is expected of them makes things run more smoothly. How will plots be assigned? What happens if a member does not maintain a plot? How will the money be handled? How often will the group meet? How will basic maintenance be handled? The Communication Committee can help disseminate the final rules to the group.

10. Create community. A community garden is all about sharing the joy of gardening with others. The Communication Committee can help create open lines of communication within your group to be sure news about the garden reaches every individual. Some groups have websites, blogs, an email distribution list, a phone tree, or a newsletter. Installing a waterproof bulletin board in the garden is a great way to announce news. Hosting potlucks or other social events in the garden helps individuals make connections with other gardeners.

(These guidelines are adapted from those established by the American Community Gardening Association.)

American Community Gardening Association

Core Beliefs of Community Organizers

- People are intelligent and capable and want to do the right thing.

- Groups can make better decisions than any one person can make alone.

- Everyone's opinion is important and is of equal value, regardless of rank or position.

- People are more committed to the ideas and plans that they have helped to create.

- People can act responsibly in assuming true accountability for their decisions.

- Groups can manage their own conflicts, behaviors, and relationships if they have the right tools, training, and support.

- The community organizing process, if well designed and honestly applied, can be trusted to achieve results.

Organizing Guidelines

- Organizers organize organizations (not people).

- People are motivated by their own self-interest.

- Personalize the target.

- Not everyone is alike.

- Do not do for others what they can do for themselves.

- People need to experience a sense of their own power.

- Power must be taken, not given.

- General education is the key to long-term success.

- Paper does not organize; people do.

(Abi-Nader, Dunnigan, and Markley, 2001)

Figure 21–11. A water source is an imperative part of any garden. This community garden has a cleanup sink for gardeners to rinse produce and dirty hands..

Kathleen Moore CC BY 2.0

Figure 21–13. This children's garden has a welcoming sign, wandering pathways and spider web web trellis inviting guests to walk through and explore.

Kathleen Moore CC BY 2.0

Figure 21–14. Think about incorporating a place for children to enjoy physical activity in the garden.

Lucy Bradley CC BY 2.0

Asset Based Community Development

Asset-based community development focuses on developing a sustainable community based on its members’ strengths and potentials. The goal is to create a community that endures and extends a positive effect on both its members and the local environment. This approach is applicable to community gardening because a successful gardening effort requires a wide range of supplies (from seeds to land and tools), ample knowledge about gardening, and willing workers. The following lists describe how community garden volunteers and members can identify assets (both materials and talents), categorize them, and manage them effectively to create and sustain a garden.

Capacity Inventory

- Identify all available local assets and connect them with one another in ways that multiply their effect.

- Base the inventory on what the group has rather than on what the group needs.

- Stay internally-focused.

- Be relationship-driven.

Categories of Assets

- Individual gifts

- Associations

- Institutions

- Land and buildings

- The local economy

Mapping Reciprocal Partnerships Activity (See Appendix H)

- On a large sheet of paper, draw a circle in the middle and write “Gardening Project” inside the circle.

- On the outside edges of the paper, write the names of partners or potential partners and draw a box around each name.

- Brainstorm ways that each partner can help the garden project.

- Draw an arrow connecting each partner to the “Garden Project” box.

- Brainstorm about what the garden project can offer each partner.

Design

Although the role of a volunteer educator is not to create a garden design or to work directly with the design committee, it is important that each volunteer has a basic understanding of design guidelines. These concepts help create a lasting, functional garden space.

Accessibility

Table beds, planter boxes, hanging baskets, vertical gardens and large flowerpots can all be used to make gardening more accessible (EPA, 2011). Listed below are some of the applicable Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requirements for making gardens accessible.

Handicap parking: One of every 25 parking spaces must be "accessible," and a sixth of the accessible spaces must be “van-accessible.”

Raised beds: At least one raised bed must be 24 to 30 inches high and 48 inches wide.

Table beds: These beds must be 27 to 34 inches high and 48 inches wide for adults and 24 to 30 inches high and 48 inches across for children (Figure 21–15).

Paths to and through the garden:

- Each path’s surface must be firm and stable, and a minimum width of 36 inches.

- Passing space should meet ADA Accessibility Guidelines (ADAAG). Where the path is less than 60 inches wide, passing spaces shall be provided at maximum intervals of 200 feet.

- Passing spaces shall be either a minimum of 60 inches by 60 inches or an intersection of two walking surfaces that provide a T-shaped space complying with ADAAG 4.2.3, provided that the arms and stem of the T-shaped space extend at least 48 inches beyond the intersection.

- Cross slope should be a maximum of 1:33.

- Running slope should adhere to one or more of the following provisions:

- 1:20 or less for any distance.

- 1:12 maximum for 50 feet. Resting intervals shall be provided at distances no greater than 50 feet apart.

- 1:10 maximum for 30 feet. Resting intervals shall be provided at distances no greater than 30 feet apart.

- Resting intervals should be a minimum length of 60 inches, have a width at least as wide as the widest portion of the trail segment leading to the resting interval, and have a slope not exceeding 1:33 in any direction.

- Where edge protection is provided, the edge protection shall have a minimum height of 3 inches.

For more detailed information as well as allowable exceptions, see the United States Access Board.

Plan for Shade and Seating

Although vegetable beds do best in full sun, gardeners do not. Shade trees on the north side of the garden can provide a protected retreat, as can vine-covered pergolas. Provide seating in the shade for gardeners to rest and visit (Figure 21–16).

Design Help

Design classes at community colleges, universities, and botanical gardens are excellent sources of information about designing a garden.

Record Keeping and Evaluation

Record keeping and evaluation of garden programs are essential to keeping a project moving in a positive, sustainable direction over the long term. Good documentation helps with garden planning, demonstrating impacts, and applying for grants.

Record Keeping

Store community garden records in a location accessible to multiple garden members, such as in a notebook that stays secured at the garden or via an online shared drive.

At a minimum track the following items:

- Plant varieties grown

- Garden maps

- Weight of garden harvests

- Photographs of garden at regular intervals

- Number of volunteers and volunteer hours

- Monetary donations and in-kind gifts

- Documentation of thank-you notes written and contact information of donors

- Number of individuals served by the garden

Evaluation

Set up a uniform evaluation strategy to ensure that your groups are evaluating the same measures in a consistent way every season. At the end of the year, data can be aggregated and garden results can be compared. Help garden members do the following:

- Identify what to measure.

- Select how to measure.

- Gather data.

- Analyze the data.

- Report to members, donors, and sponsors.

See Appendix H, Instructions for Tracking the Gardener Harvest, for more information on how to accurately measure crop yields.

Key Components of a Successful Mentor/Consultant Program

Any community garden depends on volunteer and member efforts. Volunteer educators who serve as mentors and consultants need ongoing training and networking to be successful and to feel supported by their peer group of volunteers. Experienced volunteers and researchers affiliated with the American Community Garden Association recommend the following components to a successful volunteer educator program:

Mentor training

- Introduction to community gardening

- Tours of existing community gardens, with opportunities to talk to garden leaders on site

Matching mentors to gardens

Networking: among mentors, gardeners, gardens

- Quarterly educational and social meetings and potlucks

- Website, listserv, social media

- Annual countywide spring kick-off and fall harvest festival

New community garden development

Support of existing community gardens

Policy advocacy

For more information on community gardening see Collard Greens and Common Ground: A Community Food Gardening Handbook.

Youth Gardening

Each garden is unique based on children’s needs, the population served, the amount of space available for gardening and equipment storage, the degree of irrigation, any coursework requirements, and other such differences. A community garden that involves children can be sponsored by a school or church, a scouting group, or another youth organization.

A community garden at a school may require approval from teachers and administrators. Extension Master Gardener Volunteers (EMGVs) who volunteer at a school garden do not work with children except under the direct supervision of a teacher. An EMGV may be required to register as a volunteer with the school district and to have a background check prior to working with children. Some EMGVs may serve in a mentor role working with adult leadership rather than youth.

Other youth organizations may also require a background check on volunteers. The guidelines offered here are general recommendations for creating a successful youth garden based on the research of Cromwell, Guy, and Bradley (1996). These recommendations can be adapted and tailored to the group being served.

Form a Team

- Include faculty, administrators, custodians, cafeteria staff, students, and parents.

- Welcome members with a wide variety of skills, not just gardening know-how.

- Have teacher(s) create a list of goals for the garden. See Appendix H Application for Community Garden Assistance from EMGVs.

- Discuss goals and objectives, and develop a vision.

- Build a budget, and seek in-kind and monetary support.

- Create a calendar for the year.

- Determine how children and teachers will be engaged.

Cultivate Support

- Make the garden a showcase.

- Keep administrators, maintenance crew members, and sponsors informed.

- Celebrate the garden and its supporters via newsletters, websites, and school news bulletins.

Create the Garden

- Select a highly visible site with access to sun, water, and classrooms.

- Begin with these characteristics in mind: small, beautiful, and manageable.

- Clear the site.

- Design garden.

- Use turf-paint to draw the beds and walkways. Invite students in to pretend they are gardening, and then modify the plan based on experience managing a classroom in the space.

- Create the beds.

- Install irrigation, a compost bin, a tool shed, and other garden amenities as needed.

Plant

- Use a planting calendar to plan for harvest while school is in session.

- Have the soil tested and amend it according to test recommendations at least a week before planting.

- Plant seeds and transplants.

- Keep track of what you planted to facilitate crop rotation in the future.

- Mulch to minimize evaporation and weeds and to foster soil improvement.

- Check regularly for weeds, insects, and diseases.

- Keep records of what works and what does not work. This applies to crops and gardening techniques.

Develop a Plan for the Summer

Think of ways to keep the soil healthy, and the area attractive, while school is out of session and the garden is unattended. For example, plant a cover crop to improve soil while minimizing weeds and maintenance, or solarize the soil under clear plastic to reduce weeds, disease organisms, and nematodes. Consider scheduling volunteers to water, weed, and harvest.

Working with Children

Both research and practice indicate that children respond well to educators who are flexible, fascinating, and fun. This is especially true when the classroom is a garden, where kids can explore and get dirty. Waliczek (1998) offers the following tips for working with children in a garden based on his work with the KinderGARDEN effort at Texas A&M University.

- Show them, instead of telling them (Figure 21–17).

- Ask lots of questions. “What would happen if?” “I wonder ….”

- Plan for a short attention span. Get children started on a task quickly, and keep them busy.

- Never underestimate the fascination of digging a hole.

- Children are used to instant gratification. Provide it when you can (plant radishes).

- Getting dirty is essential. Let parents know to send “work” clothes.

- Serve as a coach or facilitator—not as a lecturer.

- Foster guided discovery.

- Creepy crawly critters are cool—model fascination, not revulsion (Figure 21–18).

- Create opportunities for ownership, responsibility, and leadership.

- Involve students in planning and construction.

- Be flexible. Capitalize on teachable moments.

- Get organized ahead of time so work-time flows smoothly when children arrive.

- Never use weeding as a punishment.

- Recap garden experience by having children journal. Use age-appropriate techniques, including coloring and writing.

- Have fun!

Managing a Class in the Garden

How can volunteers accomplish their educational goals with a group of children when so many distractions can occur in a garden? Small groups, multiple volunteers, and well-organized work stations can help to keep the class fun and purposeful. Cromwell, Guy, and Bradley (1996) explain how to create a learning oasis with these tips:

- Depending on the size of the class and the garden, split the students in to groups, with only part of the students in the garden at a time (Figure 21–19).

- Have multiple volunteers to assist.

- Set up stations in the garden, each staffed by an adult or an older child, and have students cycle through the stations.

- Use a stopwatch to time sessions and keep on track.

- Place a rectangular trellis flat on the garden bed to define individual squares for students to plant.

- Have students create signage to designate planting areas.

Garden Etiquette

As does any other classroom, a youth garden requires mutual respect among educators and learners to accommodate everyone. The following rules of garden etiquette can help young gardeners and educators accomplish their mutual goals of having fun safely and learning in a garden (Cromwell, Guy, and Bradley, 1996).

- Walk on the pathways between the beds to avoid crushing plants or compacting soil.

- Ask before you pick anything.

- Harvest only from your own class plot.

- Wash everything before eating.

- Keep tools out of the path to avoid tripping.

- Hold tools below the waist.

- Place sharp edges or points of tools face down.

- Clean tools before putting them away.

- Deposit trash and recycling in designated receptacles.

- Compost plant waste.

- Wash hands after gardening.

- Share gardening information learned with family and friends.

Horticultural Therapy

Sally Haskett, Horticultural Therapist—Registered (HTR)

Since ancient times, gardens and nature have been recognized as holding the potential for solace and fulfillment. Millions of people worldwide engage in gardening for its benefits to their health and outlook on life. The process of therapeutic horticulture taps into this potential by using horticultural activities to improve human health and well-being. In the presence of a trained therapist with specific goals for clients, this process becomes the clinical practice of horticultural therapy (HT). Both therapeutic horticulture and HT are practiced in a wide variety of settings, including community, healthcare, institutional, and residential settings. Horticulture provides a medium for positive change in the realms of physical health, cognitive processes, social engagement, and emotional well-being.

The American Horticultural Therapy Association supports and advances the HT profession.

Potential activities for use in a therapeutic horticulture program are many and varied. Traditional gardening activities—such as preparing beds, sowing seeds, planting, maintenance, and harvesting—can be performed by people of all ages and abilities, with task adaptations and environmental modifications (Figure 21–20). Connections to nature evolve through gardening. These connections inherently provide opportunities for activities that teach about the cycle of life, and the activities provide endless occasions for delight with the insects and animals that inhabit our garden spaces.

Plants give prompt feedback if their needs are overlooked. Plant care and maintenance activities can be vehicles for personal growth by developing one’s sense of purpose, self-esteem, and respect for other forms of life. Simply being in the garden and observing nature can be a beneficial activity.

Volunteer educators can get involved with existing therapeutic horticulture and HT programs, or they can start a program. Current programs exist in the following arenas:

- Continuing care retirement communities

- Healthcare and rehabilitation facilities

- Hospitals

- Schools

- Public gardens

- Community gardens

- Correctional facilities

For information on existing programs and to learn about ways to get connected, check out NC State Extension Therapeutic Horticulture portal. For therapeutic horticulture and HT news, please visit the NC State Extension Therapeutic Horticulture portal.

Program commitments vary depending on the facility. At the North Carolina Botanical Garden (NCBG) in Chapel Hill, options range from a monthly commitment of two hours to a weekly commitment of four hours. For more information on volunteering in therapeutic horticulture programs at NCBG, for activity ideas, or to inquire about periodic trainings, please contact the NCBG.

Figure 21–20. A horticultural therapy program working with students who have disabilities.

Dr. Beverly J. Brown, Natashamariesilva, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Frequently Asked Questions

1. I want to start a community garden. Will Extension Master Gardener Volunteers (EMGVs) be able to help me build and maintain it?

An EMGV’s role in a community garden is as a mentor and guide. These volunteers can connect you to resources and coach you through the steps necessary to establish and maintain a successful garden. They can facilitate meetings of your garden group and help identify problem areas. They are educators, not laborers.

2. Can I apply for grant funding to start my garden?

Depending on the type of garden and the people it will serve, there are many grant programs for starting and maintaining a garden. There are grants for garden supplies as well as seeds. Be sure your garden meets the criteria outlined in the grant and that you are capable of submitting any reporting requirements. Pay careful attention to any deadlines before you apply.

References and Further Reading

Abi-Nader, J., K. Dunnigan, and K. Markley. 2001 Growing communities curriculum: Community building and organizational development through community gardening. American Community Gardening Assoc., Columbus, OH.

Baldwin, K., D. Beth, L. Bradley, N. Davé, S. Jakes, and M. Nelson. 2009. Eat smart, move more, weigh less: Growing communities through gardens. NC Dept. of Health and Human Services, Div. of Public Health, Raleigh.

Boekelheide, D. and L.K. Bradley. 2016. Collard greens and common ground: A North Carolina community food gardening handbook (AG-806). NC State Extension, NC State Univ., Raleigh.

Bradley, L. and K. Baldwin. 2013. How to organize a community garden (AG-737). NC State Extension, NC State Univ., Raleigh.

Brennan, M.J. 2013. Forsyth community gardening. N.C. Cooperative Extension, Forsyth County Extension Center, Winston-Salem.

Bucklin-Sporer, Arden, and Rachel Kathleen Pringle. 2010. How to Grow a School Garden: A Complete Guide for Parents and Teachers. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, Inc.

Chaifetz, A., L. Driscoll, C. Gunter, D. Ducharme, and B. Chapman. 2012,. Food safety for school and community gardens: A handbook for beginning and veteran garden organizers: How to reduce food safety risks. NC State Extension, NC State Univ., Raleigh.

Cohen, Whitney. 2010. Kids' Garden: 40 Fun Indoor and Outdoor Activities and Games. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Barefoot Books.

Cromwell, C., L. Guy, and L. Bradley. 1996. Success with school gardens: How to create a learning oasis in the desert. Arizona Master Gardener Press, Phoenix, AZ.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2011. Elder-accessible gardening: A community building option for brownfields redevelopment. Solid Waste and Emergency Response, U.S. EPA, Washington D.C.

Gooseman, G. 2005. Money for community gardens, p. 118–124. In ACGA Community Greening Review, 2004–2005 Special Edition. American Community Gardening Association, College Park, GA.

Kite, L. Patricia. 1995. Gardening Wizardry for Kids. Hauppauge, New York: Barron's Educational Series, Inc.

Nashville Public Health Department, Communities Putting Prevention to Work. 2009. Community garden ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) guidelines: Accessibility guidelines for gardens on metro owned or leased property. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Nashville, TN.

Peters, Elizabeth Tehle and Ellen Kirby, eds. 2008. Community Gardening. Brooklyn, New York: Brooklyn Botanic Garden.

Waliczek, T. 1998. KinderGARDEN: Some basic tips for gardeners working with kids. Dept. of Horticulture, Texas A&M Univ., College Station.

Chapter Text Hyperlinks

Community Garden Asset Inventory

10 Steps to Starting a Community Garden, by ACGA

American Horticultural Therapy Association

NC State Therapeutic Horticulture Portal

North Carolina Botanical Garden Horticultural Therapy

Start a Garden, by NC State Community Gardens Portal

Collard Greens and Common Ground: A North Carolina Community Food Gardening Handbook, by N.C. Cooperative Extension Resources

How to Organize an Allotment Community Garden, AG-737

Forsyth Community Gardening webpage

Food Safety for School + Community Gardens, by NC State & N.C. Cooperative Extension

US Environmental Protection Agency Brownfields Project

Community Gardens and the Americans with Disabilities Act

KinderGARDEN, by Texas A&M University

Vegetable Counting/Weight Measurements Guide for Recording Harvest, by Forsyth Community Gardening

For More Information

NC State Resources

- Collard Greens and Common Ground: A North Carolina Community Food Gardening Handbook,

- Community Garden Asset Inventory

- Community Gardens Portal

- Forsyth Community Gardening webpage

- How to Organize an Allotment Community Garden

- Project Learning Tree, NC State Extension Forestry Portal

- Start a Garden, by NC State Community Gardens Portal

- Vegetable Counting/Weight Measurements Guide for Recording Harvest

More NC State Resources

Other Resources

- American Community Gardening Association (ACGA)

- Community Gardens and the Americans with Disabilities Act

- Community Gardens: Different Types, by University of Kansas Cooperative Extension (4:15 minutes)

- North Carolina Community Garden Partners (Facebook page)

Youth Gardens

NC State Resources

- At Your Door Step: A Family Fact Sheet on Outdoor Play and Learning, FCS-530

- Grow For It

- Natural Learning Initiative, by NC State University

- NC State Integrated Pest Management for Schools & Child Care Facilities Portal

- Poisonous Plant Resource Sheet for Child Care Providers, by NC State University, Botany Department

Other Resources

- KinderGARDEN, by Texas A&M University

- Farm To School: School Gardens and Garden Curriculum, USDA Food & Nutrition Service

- School Gardens, by Library of Congress (17:26 minutes)

Therapeutic Horticulture

NC State Resources

Other Resources

General

XV. Contributors

Author: Lucy Bradley, Associate Professor and Extension Specialist, Urban Horticulture, NC State University; Director, NC State Extension Master Gardener program

Contributions by Extension Agents: Karen Neill, Danny Lauderdale, Kelly Groves, Colby Griffin, Pam Jones, Tim Mathews, David Goforth

Contributions by Extension Master Gardener Volunteers: Gloria Polakof, Jackie Weedon, Karen Damari, Connie Schultz, Joanne Celinski, Kim Curlee

Content Editor: Kathleen Moore, Urban Horticulturist

Copy Editor: Barbara Scott

How to cite this chapter:

Bradley, L.K. 2022. Youth, Community, and Therapeutic Gardening, Chapter 21. In: K.A. Moore, and L.K. Bradley (eds). North Carolina Extension Gardener Handbook, 2nd ed. NC State Extension, Raleigh, NC. <http://content.ces.ncsu.edu/21-youth-community-and-therapeutic-gardening>

Publication date: Feb. 1, 2022

AG-831

Other Publications in North Carolina Extension Gardener Handbook

- 1. Soils & Plant Nutrients

- 2. Composting

- 3. Botany

- 4. Insects

- 5. Diseases and Disorders

- 6. Weeds

- 7. Diagnostics

- 8. Integrated Pest Management (IPM)

- 9. Lawns

- 10. Herbaceous Ornamentals

- 11. Woody Ornamentals

- 12. Native Plants

- 13. Propagation

- 14. Small Fruits

- 15. Tree Fruit and Nuts

- 16. Vegetable Gardening

- 17. Organic Gardening

- 18. Plants Grown in Containers

- 19. Landscape Design

- 20. Wildlife

- 21. Youth, Community, and Therapeutic Gardening

- Appendix A. Garden Journaling

- Appendix B. Pesticides and Pesticide Safety

- Appendix C. Diagnostic Tables

- Appendix D. Garden Tools

- Appendix E. Season Extenders and Greenhouses

- Appendix F. History of Landscape Design

- Appendix G. Permaculture Design

- Appendix H. Community Gardening Resources

- Appendix I. More NC State Resources

- Glossary

N.C. Cooperative Extension prohibits discrimination and harassment regardless of age, color, disability, family and marital status, gender identity, national origin, political beliefs, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.

.jpg)